Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

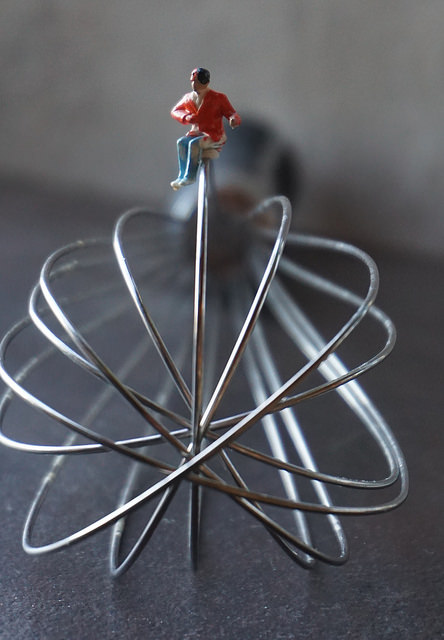

It’s time to stretch yourself.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

To find the right balance point, start with an assessment of your stretch level. List the number of projects you have and sum the number of major deliverables you’ve got to deliver. If you have more than three projects, you have too many. And if you think you take on more than three because you’re superhuman, you’re wrong. The data is clear – multitasking is a fallacy. If you have four projects you have too many. And it’s the same with three, but you’d think I was crazy if I suggested you limit your projects to two. The right balance point starts with reducing the number of projects you work on.

Now that you eliminated four or five projects and narrowed the portfolio down to the vital two or three, it’s time to list your major deliverables. Take a piece of paper and write them in a column down the left side of the page. And in a column next to the projects, categorize each of them as: -1 (done it before), 0 (done something similar), 1 (new to me), 2 (new to team), 3 (new to company), 5 (new to industry), 11 (new to world).

For the -1s, teach an entry level person how to do it and make sure they do it well. For the 0s, find someone who deserves a growth opportunity and let them have the work. And check in with them to make sure they do a good job. The idea is to free yourself for the stretch work.

For the 1s, find the best person in the team who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, do as they suggest but build on their work and take it to the next level.

For the 2s, find the best person in the company who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, build on their approach and make it your own.

For the 3s, do your research and find out who in your industry has done it before. Figure out how they did it and improve on their work.

For the 5s, do your research and figure out who has done similar work in another industry. Adapt their work to your application and twist it into something magical.

And for the 11s, they’re a special project category that live in rarified air and deserve a separate blog post of their own.

Start with where you are – evaluate your existing deliverables, cull them to a reasonable workload and assess your level of stretch. And, where it makes sense, stop doing work you’ve done before and start doing work you haven’t done yet. Stretch yourself, but be reasonable. It’s better to take one bite and swallow than take three and choke.

Image credit – filtran

Starting 101

Doing challenging work isn’t difficult. Starting challenging work is difficult.

Doing challenging work isn’t difficult. Starting challenging work is difficult.

The downside of making a mistake is far less than the downside of not starting.

If you know how it will turn out, you waited too long to start.

Stopping is fine, as long as it’s followed closely by starting.

The scope of the project you start is defined by the cash in your pocket.

If you don’t start you can’t learn.

The project doesn’t have to be all figured out before starting, you just have to start.

Starting is scary because it’s important.

Before you can start you’ve got to decide to start.

If you’re finally ready to start, you should have started yesterday.

Without starting there can be no finishing.

Starting is blocked by both the fear of success and the fear of failure.

You don’t need to be ready to start, you just need to start.

The only thing in the way of starting is you.

Image credit — Dermot O’Halloran

A Barometer for Uncertainty

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Barometers have a standard scale that measures pressure. When the summer air is clear and there are no clouds, the atmospheric pressure is high and on the rise and you should put on sun screen. When it’s hurricane season and super-low system approaches, the drops to the floor and you should evacuate. The nice thing about barometers is they are objective. On all continents, they can objectively measure the pressure and display it. No judgement, just read the scale. And regardless of the level of pressure and the number of times they measure it, the needle matches the pressure. No Kentucky windage. But novelty isn’t like that.

The only way to predict how things will go based on the level of novelty is to use judgement. There is no universal scale for novelty that works on all projects and all continents. Evaluating the level of novelty and predicting how the projects will go requires good judgement. And the only way to develop good judgment is to use bad judgment until it gets better.

All novelty isn’t created equal. And that’s the trouble. Some novelty has a big impact on the weather and some doesn’t. The trick is to know the difference. And how to tell the difference? If when you make a change in one part of the system (add novelty) and the novelty causes a big change in the function or operation of the system, that novelty is important. The system is telling you to use a light hand on the tiller. If the novelty doesn’t make much difference in system performance, drive on. The trick is to test early and often – simple tests that give thumbs-up or thumbs-down results. And if you try to run a test and you can’t get the test to run at all, there’s a hurricane is on the horizon.

When the work is new, you don’t really know which novelty will bite you. But there’s one rule: all novelty will bite you until proven otherwise. Make a list of the novel elements of the and test them crudely and quickly.

Make It Easy

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

Efficiency is overrated, especially when it interferes with effectiveness. Make it easy for effectiveness to carry the day.

You can push people off a cliff or build them a bridge to the other side. Hint – the bridge makes it easy.

Even new work is easy when people have their own reasons for doing it.

Making things easier is not easy.

Don’t tell people what to do. Make it easy for them to use their good judgement.

Set the wrong causes and conditions and creativity screeches to a halt. Set the right ones and it flows easily. Creativity is a result.

Don’t demand that people pull harder, make it easier for them to pull in the same direction.

Activity is easy to demonstrate and progress isn’t. Figure out how to make progress easier to demonstrate.

The only way to make things easier is to try to make them easier.

Image credit – Richard Hurd

To improve productivity, it’s time to set limits.

The race for productivity is on. And to take productivity to the next level, set limits.

The race for productivity is on. And to take productivity to the next level, set limits.

To reduce the time wasted by email, limit the number of emails a person can send to ten emails per day. Also, eliminate the cc function. If you send a single email to ten people, you’re done for the day. This will radically reduce the time spent writing emails and reduce distraction as fewer emails will arrive. But most importantly, it will help people figure out which information is most important to communicate and create a natural distillation of information. Lastly, limit the number of word in an email to 100. This will shorten the amount of time to read emails and further increase the density of communications.

If that doesn’t eliminate enough waste, limit the number of emails a person can read to ten emails per day. Provide the subject of the email and the sender, but no preview. Use the subject and sender to decide which emails to read. And, yes, responding to an email counts against your daily sending quota of ten. The result is further distillation of communication. People will take more time to decide which emails to read, but they’ll become more productive through use of their good judgement.

Limit the number of meetings people can attend to two per day and cap the maximum meeting length to 30 minutes. The attendees can use the meeting agenda, meeting deliverables and decisions made at the meeting to decide which meetings to attend. This will cause the meeting organizers to write tight, compelling agendas and make decisions at meetings. Wasteful meetings will go away and productivity will increase.

To reduce waiting, limit the number of projects a person can work on to a single project. Set the limit to one. That will force people to chase the information they need instead of waiting. And if they can’t get what they need, they must wait. But they must wait conspicuously so it’s clear to leaders that their people don’t have what they need to get the project done. The conspicuous waiting will help the leaders recognize the problem and take action. There’s a huge productivity gain by preventing people from working on things just to look busy.

Though harsh, these limits won’t break the system. But they will have a magical influence on productivity. I’m not sure ten is the right number of emails or two is the right number of meetings, but you get the idea – set limits. And it’s certainly possible to code these limits into your email system and meeting planning system.

Not only will productivity improve, happiness will improve because people will waste less time and get to use their judgement.

Everyone knows the systems are broken. Why not give people the limits they need and make the productivity improvements they crave?

Image credit – XoMEoX

Innovate like a professional with the Discovery Burst Event.

Recreational athletes train because they enjoy the activity and they compete so they can tell themselves (and their friends) stories about the race. Their training routines are discretionary and their finish times are all about bragging rights. Professional athletes train because it’s their job. Their training is unpleasant, stressful and ritualistic. And it’s not optional. And their performance defines their livelihood. A slow finish time negatively impacts their career. With innovation, you have a choice – do you want to do it like a recreational athlete or like a professional? Do you want to do it like it’s discretionary or like your livelihood depends on it?

Recreational athletes train because they enjoy the activity and they compete so they can tell themselves (and their friends) stories about the race. Their training routines are discretionary and their finish times are all about bragging rights. Professional athletes train because it’s their job. Their training is unpleasant, stressful and ritualistic. And it’s not optional. And their performance defines their livelihood. A slow finish time negatively impacts their career. With innovation, you have a choice – do you want to do it like a recreational athlete or like a professional? Do you want to do it like it’s discretionary or like your livelihood depends on it?

Like with the professional athlete, with innovation what worked last time is no longer good enough. Innovation demands we perform outside our comfort zone.

Goals/Objectives are the key to performing out of our comfort zone. And to bust through intellectual inertia, one of the most common business objectives is a goal to grow revenue. “Grow the top line” is the motto of the professional innovator.

To deliver on performance goals, coaches give Strategic Guidance to the professional athlete, and it’s the same for company leaders – it’s their responsibility to guide the innovation approach. The innovation teams must know if their work should focus on a new business model, a new service or a new product. And to increase the bang for the buck, an Industry-First approach is recommended, where creation of new customer value is focused within a single industry. This narrows the scope and tightens up the work. The idea is to solve a problem for an industry and sell to the whole of it. And to tighten things more, a Flagship Customer is defined with whom a direct partnership can be developed. Two attributes of a Flagship Customer – big enough to create significant sales growth and powerful enough to pull the industry in its wake.

It’s the responsibility of the sales team to identify the Flagship Customer and broker the first meeting. At the meeting, a Customer-Forward approach is proposed, where a diverse team visits the customer and dives into the details of their Goals/Objectives, their work and their problems. The objective is to discover new customer outcomes and create a plan to satisfy them. The Discovery Burst Event (DBE) is the mechanism to do the work It’s a week-long event where marketing, sales, engineering, manufacturing and technical services perform structured interviews to get to the root of the customer’s problems AND, in a Go-To-The-Work way, walk their processes and use their eyeballs to discover solutions to problems the customer didn’t know they had. The DBE culminates with a report out to leaders of the Flagship Company where new customer outcome statements are defined along with a plan to assess the opportunities (impact/effort) and come back with proposals to satisfy the most important outcome statements.

After the DBE, the team returns home and evaluates and prioritizes the opportunities. As soon as possible, the prioritization decisions are presented to the Flagship Customer along with project plans to create novel solutions. In a tactical sense, there are new opportunities to sell existing products and services. And in a strategic sense, there are opportunities to create new business models, new services and new products to reinvent the industry.

In the short term, sales of existing products increase radically. And in the longer term, where new solutions must be created, the Innovation Burst Event (IBE) process is used to quickly create new concepts and review them with the customer in a timely way. And because the new concepts solve validated customer problems, by definition the new concepts will be valued by the customer. In a Customer-Forward way, the new concepts created by the IBE are driven by the customer’s business objectives and their problems.

This Full Circle approach to innovation pushes everyone out of their comfort zones to help them become professional innovators. Company leadership must stick out their necks and give strategic guidance, sales teams must move to a trusted advisor role, engineering and marketing teams must learn to listen to (and value) the customer’s perspective, and new ways of working – the Discovery Burst Event (DBE) and Innovation Burst Event (IBE) – must be embraced. But that’s what it takes to become professional innovators.

Innovation isn’t a recreational sport, and it’s time to behave that way.

Image credit – Lwp Kommunikáció

The WHY and HOW of Innovation

Innovation is difficult because it demands new work. But, at a more basic level, it’s difficult because it requires an admission that the way you’ve done things is no longer viable. And, without public admission the old way won’t carry the day, innovation cannot move forward. After the admission there’s no innovation, but it’s one step closer.

Innovation is difficult because it demands new work. But, at a more basic level, it’s difficult because it requires an admission that the way you’ve done things is no longer viable. And, without public admission the old way won’t carry the day, innovation cannot move forward. After the admission there’s no innovation, but it’s one step closer.

After a public admission things must change, a cultural shift must happen for innovation to take hold. And for that, new governance processes are put in place, new processes are created to set new directions and new mechanisms are established to make sure the new work gets done. Those high-level processes are good, but at a more basic level, the objectives of those process areto choose new projects, manage new projects and allocate resources differently. That’s all that’s needed to start innovation work.

But how to choose projects to move the company toward innovation? What are the decision criteria? What is the system to collect the data needed for the decisions? All these questions must be answered and the answers are unique to each company. But for every company, everything starts with a top line growth objective, which narrows to an approach based on an industry, geography or product line, which then further necks down to a new set of projects. Still no innovation, but there are new projects to work on.

The objective of the new projects is to deliver new usefulness to the customer, which requires new technologies, new products and, possibly, new business models. And with all this newness comes increased uncertainty, and that’s the rub. The new uncertainty requires a different approach to project management, where the main focus moves from execution of standard tasks to fast learning loops. Still no innovation, but there’s recognition the projects must be run differently.

Resources must be allocated to new projects. To free up resources for the innovation work, traditional projects must be stopped so their resources can flow to the innovation work. (Innovation work cannot wait to hire a new set of innovation resources.) Stopping existing projects, especially pet projects, is a major organizational stumbling block, but can be overcome with a good process. And once resources are allocated to new projects, to make sure the resources remain allocated, a separate budget is created for the innovation work. (There’s no other way.) Still no innovation, but there are people to do the innovation work.

The only thing left to do is the hardest part – to start the innovation work itself. And to start, I recommend the IBE (Innovation Burst Event). The IBE starts with a customer need that is translated into a set of design challenges which are solved by a cross-functional team. In a two-day IBE, several novel concepts are created, each with a one page plan that defines next steps. At the report-out at the end of the second day, the leaders responsible for allocating the commercialization resources review the concepts and plans and decide on next steps. After the first IBE, innovation has started.

There’s a lot of work to help the organization understand why innovation must be done. And there’s a lot of work to get the organization ready to do innovation. Old habits must be changed and old recipes must be abandoned. And once the battle for hearts and minds is won, there’s an equal amount of work to teach the organization how to do the new innovation work.

It’s important for the organization to understand why innovation is needed, but no customer value is delivered and no increased sales are booked until the organization delivers a commercialized solution.

Some companies start innovation work without doing the work to help the organization understand why innovation work is needed. And some companies do a great job of communicating the need for innovation and putting in place the governance processes, but fail to train the organization on how to do the innovation work.

Truth is, you’ve got to do both. If you spend time to convince the organization why innovation is important, why not get some return from your investment and teach them how to do the work? And if you train the organization how to do innovation work, why not develop the up-front why so everyone rallies behind the work?

Why isn’t enough and how isn’t enough. Don’t do one without the other.

Image credit — Sam Ryan

How To Reduce Innovation Risk

The trouble with innovation is it’s risky. Sure, the upside is nice (increased sales), but the downside (it doesn’t work) is distasteful. Everyone is looking for the magic pill to change the risk-reward ratio of innovation, but there is no pill. Though there are some things you can do to tip the scale in your favor.

The trouble with innovation is it’s risky. Sure, the upside is nice (increased sales), but the downside (it doesn’t work) is distasteful. Everyone is looking for the magic pill to change the risk-reward ratio of innovation, but there is no pill. Though there are some things you can do to tip the scale in your favor.

All problems are business problems. Problem solving is the key to innovation, and all problems are business problems. And as companies embrace the triple bottom line philosophy, where they strive to make progress in three areas – environmental, social and financial, there’s a clear framework to define business problems.

Start with a business objective. It’s best to define a business problem in terms of a shortcoming in business results. And the holy grail of business objectives is the growth objective. No one wants to be the obstacle, but, more importantly, everyone is happy to align their career with closing the gap in the growth objective. In that way, if solving a problem is directly linked to achieving the growth objective, it will get solved.

Sell more. The best way to achieve the growth objective is to sell more. Bottom line savings won’t get you there. You need the sizzle of the top line. When solving a problem is linked to selling more, it will get solved.

Customers are the only people that buy things. If you want to sell more, you’ve got to sell it to customers. And customers buy novel usefulness. When solving a problem creates novel usefulness that customers like, the problem will get solved. However, before trying to solve the problem, verify customers will buy what you’re selling.

No-To-Yes. Small increases in efficiency and productivity don’t cause customers to radically change their buying habits. For that your new product or service must do something new. In a No-To-Yes way, the old one couldn’t but the new one can. If solving the problem turns no to yes, it will get solved.

Would they buy it? Before solving, make sure customers will buy the useful novelty. (To know, clearly define the novelty in a hand sketch and ask them what they think.) If they say yes, see the next question.

Would it meet our growth objectives? Before solving, do the math. Does the solution result in incremental sales larger than the growth objective? If yes, see the next question.

Would we commercialize it? Before solving, map out the commercialization work. If there are no resources to commercialize, stop. If the resources to commercialize would be freed up, solve it.

Defining is solving. Up until now, solving has been premature. And it’s still not time. Create a functional model of the existing product or service using blocks (nouns) and arrows (verbs). Then, to create the problem(s), add/modify/delete functions to enable the novel usefulness customers will buy. There will be at least one problem – the system cannot perform the new function. Now it’s time to take a deep dive into the physics and bring the new function to life. There will likely be other problems. Existing functions may be blocked by the changes needed for the new function. Harmful actions may develop or some functions will be satisfied in an insufficient way. The key is to understand the physics in the most complete way. And solve one problem at a time.

Adaptation before creation. Most problems have been solved in another industry. Instead of reinventing the wheel, use TRIZ to find the solutions in other industries and adapt them to your product or service. This is a powerful lever to reduce innovation risk.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem. And you know it’s the wrong problem if the solution doesn’t: solve a business problem, achieve the growth objective, create more sales, provide No-To-Yes functionality customers will buy, and you won’t allocate the resources to commercialize.

And if the problem successfully runs the gauntlet and is worth solving, spend time to define it rigorously. To understand the bedrock physics, create a functional of the system, add the new functionality and see what breaks. Then use TRIZ to create a generic solution, search for the solution across other industries and adapt it.

The key to innovation is problem solving. But to reduce the risk, before solving, spend time and energy to make sure it’s the right problem to solve.

It’s far faster to solve the right problem slowly than to solve the wrong one quickly.

Image credit – Kate Ter Haar

See differently to solve differently.

There are many definitions for creativity and innovation, but none add meaningfully to how the work is done. Though it’s clear why the work is important – creativity and innovation underpin corporate prosperity and longevity – it’s especially helpful to know how to do it.

There are many definitions for creativity and innovation, but none add meaningfully to how the work is done. Though it’s clear why the work is important – creativity and innovation underpin corporate prosperity and longevity – it’s especially helpful to know how to do it.

At the most basic level, creativity and innovation are about problem solving. But it’s a special flavor of problem solving. Creativity and innovation are about problems solving new problems in new ways. The glamorous part is ‘solving in new ways’ and the important part is solving new problems.

With continuous improvement the same problems are solved over and over. Change this to eliminate waste, tweak that to reduce variation, adjust the same old thing to make it work a little better. Sure, the problems change a bit, but they’re close cousins to the problems to the same old problems from last decade. With discontinuous improvement (which requires high levels of creativity and innovation) new problems are solved. But how to tell if the problem is new?

Solving new problems starts with seeing problems differently.

Systems are large and complicated, and problems know how to hide in the nooks and crannies. In a Where’s Waldo way, the nugget of the problem buries itself in complication and misuses all the moving parts as distraction. Problems use complication as a cloaking mechanism so they are not seen as problems, but as symptoms.

Telescope to microscope. To see problems differently, zoom in. Create a hand sketch of the problem at the microscopic level. Start at the system level if you want, but zoom in until all you see is the problem. Three rules: 1. Zoom in until there are only two elements on the page. 2. The two elements must touch. 3. The problem must reside between the two elements.

Noun-verb-noun. Think hammer hits nail and hammer hits thumb. Hitting the nail is the reason people buy hammers and hitting the thumb is the problem.

A problem between two things. The hand sketch of the problem would show the face of the hammer head in contact with the surface of the thumb, and that’s all. The problem is at the interface between the face of the hammer head and the surface of the thumb. It’s now clear where the problem must be solved. Not where the hand holds the shaft of the hammer, not at the claw, but where the face of the hammer smashes the thumb.

Before-during-after. The problem can be solved before the hammer smashes the thumb, while the hammer smashes the thumb, or after the thumb is smashed. Which is the best way to solve it? It depends, that’s why it must be solved at the three times.

Advil and ice. Solving the problem after the fact is like repair or cleanup. The thumb has been smashed and repercussions are handled in the most expedient way.

Put something between. Solving the problem while it happens requires a blocking or protecting action. The hammer still hits the thumb, but the protective element takes the beating so the thumb doesn’t.

Hand in pocket. Solving the problem before it happens requires separation in time and space. Before the hammer can smash the thumb it is moved to a safe place – far away from where the hammer hits the nail.

Nail gun. If there’s no way for the thumb to get near the hammer mechanism, there is no problem.

Cordless drill. If there are no nails, there are no hammers and no problem.

Concrete walls. If there’s no need for wood, there’s no need for nails or a hammer. No hammer, no nails, no problem.

Discerning between symptoms and problems can help solve new problems. Seeing problems at the micro level can result in new solutions. Looking closely at problems to separate them time and space can help see problems differently.

Eliminating the tool responsible for the problem can get rid of the problem of a smashed thumb, but it creates another – how to provide the useful action of the driven nail. But if you’ve been trying to protect thumbs for the last decade, you now have a chance to design a new way to fasten one piece of wood to another, create new walls that don’t use wood, or design structures that self-assemble.

Image credit – Rodger Evans

Innovation and the Mythical Idealized Future State

When it’s time to innovate, the first task is usually to define the Idealized Future State (IFS). The IFS is a word picture that captures what it looks like when the innovation work has succeeded beyond our wildest dreams. The IFS, so it goes, is directional so we can march toward the right mountain and inspirational so we can sustain our pace over the roughest territory.

When it’s time to innovate, the first task is usually to define the Idealized Future State (IFS). The IFS is a word picture that captures what it looks like when the innovation work has succeeded beyond our wildest dreams. The IFS, so it goes, is directional so we can march toward the right mountain and inspirational so we can sustain our pace over the roughest territory.

For the IFS to be directional, it must be aimed at something – a destination. But there’s a problem. In a sea of uncertainty, where the work has never been done before and where there are no existing products, services or customers, there are an infinite number of IFRs/destinations to guide our innovation work. Open question – When the territory is unknown, how do we choose the right IFS?

For the IFS to be inspirational, it must create yearning for something better (the destination). And for the yearning to be real, we must believe the destination is right for us. Open question – How can we yearn for an IFS when we really can’t know it’s the right destination?

Maps aren’t the territory, but they are a collection of all possible destinations within the design space of the map. If you have the right map, it contains your destination. And for a long time now, the old paper maps have helped people find their destinations. But on their own maps don’t tell us the direction to drive. If you have a map of the US and you want to drive to Kansas, in which direction do you drive? It depends. If in California, drive east; if in Mississippi, drive north; if in New Hampshire, drive west; and in Minnesota, drive south. If Kansas is your idealized future state, the map alone won’t get your there. The direction you drive depends on your location.

GPS has been a nice addition to maps. Enter the destination on the map, ask the satellites to position us globally and it’s clear which way to drive. (I drive west to reach Kansas.) But the magic of GPS isn’t in the electronic map, GPS is magic because it solves the location problem.

Before defining the idealized future state, define your location. It grounds the innovation work in the reality of what is, and people can rally around what is. And before setting the innovation direction with the IFS, define the next problems to solve and walk in their direction.

Image credit – Adrian Brady

Full Circle Innovation

It’s not enough to sell things to customers, because selling things is transactional and, over time, transactional selling deteriorates into selling on price. And selling on price is a race to the bottom.

It’s not enough to sell things to customers, because selling things is transactional and, over time, transactional selling deteriorates into selling on price. And selling on price is a race to the bottom.

Sales must move from transactional to relational, where people in the sales organization become trusted advisers and then something altogether deeper. At this deeper level of development, the sales people know the business as well as the customer, know where the customer wants to go and provide unique perspective and thoughtful insight. That’s quite a thing for sales, but it’s not enough. Sales must become the conduit that brings the entire company closer to the customer and their their work.

When the customer is trying to figure out what’s next, sales brings in a team of marketing, R&D and manufacturing to triangulate on the future. The objective is to develop deep understanding of the customer’s world. The understanding must go deeper than the what’s. The learning must scrape bottom and get right down to the bedrock why’s.

To get to bedrock, marketing leads learning sessions with the customer. And it all starts by understanding the work. What does the customer do? Why is it done that way? What are the most important processes? How did they evolve? Why do they flow the way they do? These aren’t high-level questions, they are low-level, specific questions, done in front of the actual work.

The mantra – Go to the work.

When the learning sessions are done well, marketing includes experts in manufacturing and R&D. Manufacturing brings their expertise in understanding process and R&D brings their expertise in products and technologies. And to understand the work the deepest way, the tool of choice is the Value Stream Map (VSM).

Cross-organization teams are formed (customer, sales, marketing, manufacturing, and R&D) and are sent out to create Value Steam Maps of the most important processes. (Each team is supported by a VSM expert.) Once the maps are made, all the teams come back together to review the them and identify the fundamental constraints and how to overcome them. The solutions are not limited to new product offerings, rather the solutions could be training, process changes, policy changes, organizational changes or business model changes.

Not all the problems are solved in the moment. After the low hanging fruit is picked, the real work begins. After returning home, marketing and R&D work together to formulate emergent needs and create new ways to meet them. The tool of choice is the IBE (Innovation Burst Event).

To prepare for the IBE, marketing and R&D formalize emergent needs and create Design Challenges to focus the IBE teams. Solving the Design Challenges breaks the conflicts creates novel solutions that meet the unmet needs. In this way, the IBE is a pull process – customer needs create the pull for a solution.

The IBE is a one or two-day event where teams solve the Design Challenges by building conceptual prototypes (thinking prototypes). Then, they vote on the most interesting concepts and create a build plan (who, what, when). The objective of the build plan is to create a Diabolically Simple Prototype (DSP), a functional prototype that demonstrates the new functionality. What makes it diabolical is quick build time. At the end of the IBE is a report out of the build plan to the leader who can allocate the resources to execute it.

In a closed-loop way, once the DSP is built, sales arranges another visit to the customer to demonstrate the new solution. And because the prototype designed to fulfill the validated customer need, by definition, the prototype will be valuable to the customer.

This full circle process has several novel elements, but the magic is in the framework that brings everyone together. With the process, two companies can work together effectively to achieve shared business objectives. And, because the process brings together multiple functions and their unique perspectives, the solutions are well-thought-out and grounded in the diversity of the collective.

Image credit – Gerry Machen

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski