Archive for April, 2019

Before solving, learn more about the problem.

Ideas are cheap, but converting them into a saleable product and building the engine to make it all happen is expensive. Before spending the big money, spend more time than you think reasonable to answer these three questions.

Ideas are cheap, but converting them into a saleable product and building the engine to make it all happen is expensive. Before spending the big money, spend more time than you think reasonable to answer these three questions.

Is the problem big enough? There’s no sense spending the time and money to solve a problem unless you have a good idea the payback is worth the cost. Before spending the money to create the solution, spend the time to assess the benefits that will come from solving the problem.

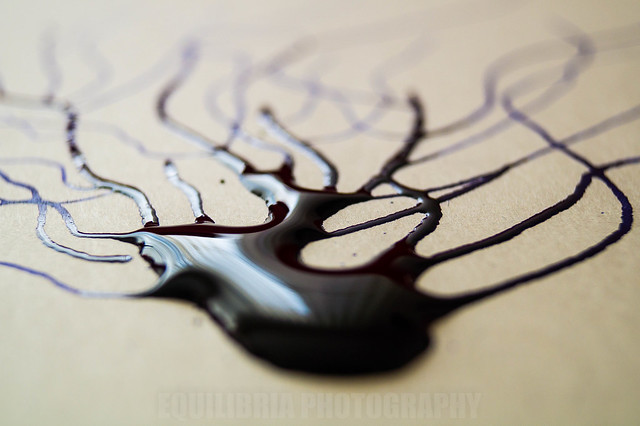

Before you can decide if the problem is big enough, you have to define the problem and know who has it. One of the best ways to do this is to define how things are done today. Draw a block diagram that defines the steps potential customers follow or draw a picture of how they do things today. Define the products/services they use today and ask them what it would mean if you solved their problem. What’s particularly difficult at this point is they may not know they have a problem.

But before moving on, formalize who has the problem. Define the attributes of the potential customers and figure out how many have the same attributes and, possibly, the same problem. Define the segments narrowly to make sure each segment does, in fact, have the same problem. There will be a tendency to paint with broad strokes to increase the addressable market, but stay narrow and maintain focus on a tight group of potential customers.

Estimate the value of the solution based on how it compares to the existing alternative. And the only ones who can give you this information are the potential customers. And the only way they can give you the information is if you interview them and watch them work. And with this detailed knowledge, figure out the number of potential customers who have the problem. Do all this BEFORE any solving.

Will they pay for it? The only way to know if potential customers will pay for your solution is to show them an offering – a description of your value proposition and how it differs from the existing alternatives, a demo (a mockup of a solution and not a functional prototype) and pricing. (See LEANSTACK for more on an offering.) There will be a tendency to wait until the solution is ready, but don’t wait. And there will be a reluctance attach a price to the solution, but that’s the only way you’ll know how much they value your solution. And there will be difficulty defining a tight value proposition because that requires you to narrowly define what the solution does for the potential customer. And that’s scary because the value proposition will be clear and understandable and the potential customer will understand it well enough to decide they if they like it or not.

If you don’t assign a price and ask them to buy it, you’ll never know if they’ll buy it in real life.

Can you deliver it? List all the elements that must come together. Can you make it? Can you sell it? Can you ship it? Can you service it? Are your partners capable and committed? Do you have the money do put everything in place?

Like with a chain, it takes one bad link to make the whole thing fall apart. Figure out if any of your links are broken or missing. And don’t commit resources until they’re all in place and ready to go.

Image credit — Matthias Ripp

Innovation isn’t uncertain, it’s unknowable.

Where’s the Marketing Brief? In product development, the Marketing team creates a document that defines who will buy the new product (the customer), what needs are satisfied by the new product and how the customer will use the new product. And Marketing team also uses their crystal ball to estimate the number of units the customers will buy, when they’ll buy it and how much they’ll pay. In theory, the Marketing Brief is finalized before the engineers start their work.

Where’s the Marketing Brief? In product development, the Marketing team creates a document that defines who will buy the new product (the customer), what needs are satisfied by the new product and how the customer will use the new product. And Marketing team also uses their crystal ball to estimate the number of units the customers will buy, when they’ll buy it and how much they’ll pay. In theory, the Marketing Brief is finalized before the engineers start their work.

With innovation, there can be no Marketing Brief because there are no customers, no product and no technology to underpin it. And the needs the innovation will satisfy are unknowable because customers have not asked for the them, nor can the customer understand the innovation if you showed it to them. And how the customers will use the? That’s unknowable because, again, there are no customers and no customer needs. And how many will you sell and the sales price? Again, unknowable.

Where’s the Specification? In product development, the Marketing Brief is translated into a Specification that defines what the product must do and how much it will cost. To define what the product must do, the Specification defines a set of test protocols and their measurable results. And the minimum performance is defined as a percentage improvement over the test results of the existing product.

With innovation, there can be no Specification because there are no customers, no product, no technology and no business model. In that way, there can be no known test protocols and the minimum performance criteria are unknowable.

Where’s the Schedule? In product development, the tasks are defined, their sequence is defined and their completion dates are defined. Because the work has been done before, the schedule is a lot like the last one. Everyone knows the drill because they’ve done it before.

With innovation, there can be no schedule. The first task can be defined, but the second cannot because the second depends on the outcome of the first. If the first experiment is successful, the second step builds on the first. But if the first experiment is unsuccessful, the second must start from scratch. And if the customer likes the first prototype, the next step is clear. But if they don’t, it’s back to the drawing board. And the experiments feed the customer learning and the customer learning shapes the experiments.

Innovation is different than product development. And success in product development may work against you in innovation. If you’re doing innovation and you find yourself trying to lock things down, you may be misapplying your product development expertise. If you’re doing innovation and you find yourself trying to write a specification, you may be misapplying your product development expertise. And if you are doing innovation and find yourself trying to nail down a completion date, you are definitely misapplying your product development expertise.

With innovation, people say the work is uncertain, but to me that’s not the right word. To me, the work is unknowable. The customer is unknowable because the work hasn’t been done before. The specification is unknowable because there is nothing for comparison. And the schedule in unknowable because, again, the work hasn’t been done before.

To set expectations appropriately, say the innovation work is unknowable. You’ll likely get into a heated discuss with those who want demand a Marketing Brief, Specification and Schedule, but you’ll make the point that with innovation, the rules of product development don’t apply.

Image credit — Fatih Tuluk

The Trust Network II

I stand by my statement that trust is the most important element in business (see The Trust Network.)

I stand by my statement that trust is the most important element in business (see The Trust Network.)

The Trust Network are the group of people who get the work done. They don’t do the work to get promoted, they just do the work because they like doing the work. They don’t take others’ credit (they’re not striving,) they just do the work. And they help each other do the work because, well, it’s the right thing to do.

Sometimes, they use their judgement to protect the company from bad ideas. But to be clear, they don’t protect the Status Quo. They use their good judgement to decide if a new idea has merit, and if it doesn’t, they try to shape it. And if they can’t shape it, they block it. Their judgement is good because their mutual trust allows them to talk openly and honestly and listen to each other. And through the process, they come to a decision and act on it.

But there’s another side to the Trust Network. They also bring new ideas to the company.

Trying new things is scary, but the Trust Network makes it safe. When someone has a good idea, the Network positively reinforces the goodness of the idea and recommends a small experiment. And when one installment of positivity doesn’t carry the day, the Trust Network comes together to create the additional positivity need to grow the idea into an experiment.

To make it safe, the Trust Network knows to keep the experiment small. If the small experiment doesn’t go as planned, they know there will be no negative consequences. And if the experiment’s results do attract attention, they dismiss the negativity of failure and talk about the positivity of learning. And if there is no money to run the experiment, they scare it up. They don’t stop until the experiment is completed.

But the real power of the Trust Network shows its hand after the successful experiment. The toughest part of innovation is the “now what” part, where successful experiments go to die. Since no one thought through what must happen to convert the successful experiment to a successful product, the follow-on actions are undefined and unbudgeted and the validated idea dies. But the Trust Network knows all this, so they help the experimenter define the “then what” activities before the experiment is run. That way, the resources are ready and waiting when the experiment is a success. The follow-on activities happen as planned.

The Trust Network always reminds each other that doing new things is difficult and that it’s okay that the outcome of the experiment is unknown. In fact, they go further and tell each other that the outcome of the experiment is unknowable. Regardless of the outcome of the experiment, the Trust Network is there for each other.

To start a Trust Network, find someone you trust and trust them. Support their new ideas, support their experiments and support the follow-on actions. If they’re afraid, tell them to be afraid and run the experiment. If they don’t have the resources to run the experiment, find the resources for them. And if they’re afraid they won’t get credit for all the success, tell them to trust you.

And to grow your Trust Network, find someone else you trust and trust them. And, repeat.

Image credit — Rolf Dietrich Brecher

The Trust Network

Trust is the most important element in business. It’s not organizational authority, it’s not alignment, it’s not execution, it’s not best practices, it’s not competitive advantage and it’s not intellectual property. It’s trust.

Trust is the most important element in business. It’s not organizational authority, it’s not alignment, it’s not execution, it’s not best practices, it’s not competitive advantage and it’s not intellectual property. It’s trust.

Trust is more powerful than the organizational chart. Don’t believe me? Draw the org chart and pretend the person at the top has a stupid idea and they try to push down into the organization. When the top person pushes, the trust network responds to protect the company. After the unrealistic edict is given, the people on the receiving end (the trust network) get together in secret and hatch a plan to protect the organization from the ill-informed, but well-intentioned edict. Because we trust each other, we openly share our thoughts on why the idea is less than good. We are not afraid to be judged by members of trust network and, certainly, we don’t judge other members of the network. And once our truths are shared, the plan starts to take shape.

The trust network knows how things really work because we’ve worked shoulder-to-shoulder to deliver the most successful new products and technologies in company history. And through our lens of what worked, we figure out how to organize the resistance. And with the plan roughed out, we reach out to our trust network. We hold meetings with people deep in the organization who do the real work and tell them about the plan to protect the company. You don’t know who those people are, but we do.

If you don’t know about the trust network, it’s because you’re not part of it. But, trust me, it’s real. We meet right in front of you, but you don’t see us. We coordinate in plain sight, but we’re invisible. We figure out how things are going to go, but we don’t ask you or tell you. And you don’t know about us because we don’t trust you.

When the trust network is on your side, everything runs smoothly. The right resources flow to the work, the needed support somehow finds the project and, mysteriously, things get done faster than imagined. But when the trust network does not believe in you and your initiative, the wheels fall off. Things that should go smoothly, don’t, resources don’t flow to the work and, mysteriously, no one knows why.

You can push on the trust network, but you can’t break us. You can use your control mechanisms, but we will feign alignment until your attention wanes. And once you’re distracted, we’ll silently help the company do the right thing. We’re more powerful than you because you’re striving and we’re thriving. We can wait you out because we don’t need the next job. And, when the going gets tough, we’ll stick together because we trust each other.

Trust is powerful because it must be earned. With years of consistent behavior, where words match actions year-on-year, strong bonds are created. In that way, trust can’t be faked. You’ve either earned it or you haven’t. And when you’ve earned trust, people in the network take you seriously and put their faith in you. And when you haven’t earned trust, people in the network are not swayed by your words or your trendy initiative. We won’t tell you we don’t believe in you, but we won’t believe in you.

The trust network won’t invite you to join. The only way in is to behave in ways that make you trustworthy. When you think the company is making a mistake, say it. The trust network likes when your inner thoughts match your outer words. When someone needs help, help them. Don’t look for anything in return, just help them. When someone is about to make a mistake, step in and protect them from danger. Don’t do it for you, do it for them. And when someone makes a mistake, take the bullets. Again, do it for them.

After five or ten years of unselfish, trustworthy behavior, you’ll find yourself in meetings where the formal agenda isn’t really the agenda. In the meeting you’ll chart the company’s path without the need to ask permission. And you’ll be listened to even when your opinion is contrary to the majority. And you’ll be surrounded by people that care about you.

Even if you don’t believe in the trust network, it’s a good idea to behave in a trustworthy way. It’s good for you and the company. And when the trust network finally accepts you, you’ll be doubly happy you behaved in a trustworthy way.

Image credit — manfred majer

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski