Archive for the ‘Seven Wastes’ Category

A Recipe to Grow Revenue Now

If you want to grow the top line right now, create a hard constraint – the product cannot change – and force the team to look for growth outside the product. Since all the easy changes to the product have been made, without a breakthrough the small improvements bring diminishing returns. There’s nothing left here. Make them look elsewhere.

If you want to grow the top line right now, create a hard constraint – the product cannot change – and force the team to look for growth outside the product. Since all the easy changes to the product have been made, without a breakthrough the small improvements bring diminishing returns. There’s nothing left here. Make them look elsewhere.

If you want to grow the top line without changing the product, make it easier for customers to buy the products you already have.

If you want to make it easier for customers to buy what you have, eliminate all things that make buying difficult. Though this sounds obvious and trivial, it’s neither. It’s exceptionally difficult to see the waste in your processes from the customers’ perspective. The blackbelts know how to eliminate waste from the company’s perspective, but they’ve not been taught to see waste from the customers’ perspective. Don’t believe me? Look at the last three improvements you made to the customers’ buying process and ask yourself who benefitted from those changes. Odds are, the changes you made reduced the number of people you need to process the transactions by pushing the work back into the customers’ laps. This is the opposite of making it easier for your customers to buy.

Have you ever run a project to make it easier for customers to buy from you?

If you want to make it easier for customers to buy the products you have, pretend you are a customer and map their buying process. What you’ll likely learn is that it’s not easy to buy from you.

How can you make it easier for the customer to choose the right product to buy? Please don’t confuse this with eliminating the knowledgeable people who talk on the phone with customers. And, fight the urge to display all your products all at once. Minimize their choices, don’t maximize them.

How can you make it easier for customers to buy what they bought last time? A hint: when an existing customer hits your website, the first thing they should see is what they bought last time. Or, maybe, a big button that says – click here to buy [whatever they bought last time]. This, of course, assumes you can recognize them and can quickly match them to their buying history.

How can you make it easier for customers to pay for your product? Here’s a rule to live by: if they don’t pay, you don’t sell. And here’s another: you get no partial credit when a customer almost pays.

As you make these improvements, customers will buy more. You can use the incremental profits to fund the breakthrough work to obsolete your best products.

“Shopping Cart” by edenpictures is licensed under CC BY 2.0

A three-pronged approach for making progress

When you’re looking to make progress, the single most important skill is to see waiting as waiting.

The first place to look for waiting is the queue in front of a shared resource. Like taking a number at the deli, you queue up behind the work that got there first and your work waits its turn. And when the situation turns bad, prioritization meeting spring up to argue about the importance of one bit of work over another. Those meetings are a sure-fire sign of ineffectiveness. When these meetings spring up, it’s time to increase capacity of the shared resource to stop waiting and start making progress.

Another place to look for waiting is the process to schedule a meeting with high-level leaders. Their schedules are so full (efficiency over effectiveness) the next open meeting slot is next month. Let me translate – “As a senior leader and decision maker, I want you to delay the business-critical project until I carve out an hour so you can get me up to speed and I can tell you what to do.” The best project managers don’t wait. They schedule the meeting three weeks from now, make progress like their hair is on fire and provide a status update when the meeting finally happens. And the smartest leaders thank the project managers for using their discretion and good judgment.

A variant of the wait-for-the-most-important-leader theme is the never-ending-series-of-meetings-where-no-decisions-are-made scenario. The classic example of this unhealthy lifestyle is where a meeting to make a decision spawns a never-ending series of weekly meetings with 12 or more regular attendees where the initial agenda of making a decision death spirals into an ever-changing, and ultimately disappearing agenda. Everyone keeps meeting, but no one remembers why. And the decision is never made. The saddest part is that no one remembers that project is blocked by the non-decision.

The first place to look for waiting is the queue in front of a shared resource. Like taking a number at the deli, you line up behind the work that got there first and your work waits its turn. And when the situation turns bad, prioritization meeting spring up to argue about the importance of one bit of work over another. Those meetings are a sure-fire sign of ineffectiveness. It’s time to increase capacity of the shared resource to stop waiting and start making progress.

And the deadliest waiting is the waiting that we no longer see as waiting. The best example of this crippling non-waiting waiting is when we cannot work the critical path and, instead, we work on a task of secondary importance. We kid ourselves into thinking we’re improving efficiency when, in fact, we’re masking the waiting and enabling the poor decision making that starved the project of the resources it needs to work the critical path. Whether you work a non-critical path task or not, when you can’t work the critical path for a week, you delay project completion by a week. That’s a rule.

Instead of spending energy working a non-critical path task, it’s better for everyone if you do nothing. Sit at your desk and play solitaire on your computer or surf the web. Do whatever it takes for your leader to recognize you’re not making progress. And when your leader tries to chastise you, tell them to do their job and give you what you need to work the critical path.

There’s two types of work – value-added work and non-value-added work. Value-added work happens when you complete a task on the critical path. Non-value-added work happens when you wait, when you do work that’s not on the critical path, when you get ready to do work and when you clean up after doing work. In most processes, the ratio of non-value-added to value-added work is 20:1 to 200:1. Meaning, for every hour of value-added work there are twenty to two hundred hours of non-value-added work.

If you want to make progress, don’t improve how you do your value-added work. Instead, identify the non-value-added work you can stop and stop it. In that way, without changing how you do an hour long value-added task, you can eliminate twenty to two hundred hours wasted effort.

Here’s the three-pronged approach for making progress:

Prong one – eliminate waiting. Prong two – eliminate waiting. Prong three – eliminate waiting.

Image credit João Lavinha

A Recipe for Unreasonable Profits

There’s an unnatural attraction to lean – a methodology to change the value stream to reduce waste. And it’s the same with Design for Manufacturing (DFM) – a methodology to design out cost of your piece-parts. The real rain maker is Design for Assembly (DFA) which eliminates parts altogether (50% reductions are commonplace.) DFA is far more powerful.

There’s an unnatural attraction to lean – a methodology to change the value stream to reduce waste. And it’s the same with Design for Manufacturing (DFM) – a methodology to design out cost of your piece-parts. The real rain maker is Design for Assembly (DFA) which eliminates parts altogether (50% reductions are commonplace.) DFA is far more powerful.

The cost for a designed out part is zero. Floor space for a designed out part is zero. Transportation cost for a designed out part is zero. (Can you say Green?) From a lean perspective, for a designed out part there is zero waste. For a designed out part the seven wastes do not apply.

Here’s a recipe for unreasonable profits:

Design out half the parts with DFA. For the ones that remain, choose the three highest cost parts and design out the cost. Then, and only then, do lean on the manufacturing processes.

For a video version of the post, see this link: (Video embedded below.)

A Recipe for Unreasonable Profits.

Too afraid to make money and create jobs.

What if you could double your factory throughput without adding people?

What if you could double your factory throughput without adding people?

What if you could reduce your product costs by 50%?

How much money would you make?

How many jobs would you create?

Why aren’t you doing it?

What are you afraid of?

Pareto’s Three Lenses for Product Design

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 1 – Time is short, so make sure you’re working on the most important stuff.

Axiom 2 – You can’t design out what you can’t see.

In product development, these two axioms can keep you out of trouble. They’re two sides of the same coin, but I’ll describe them one at a time and hope it comes together in the end.

With Axiom 1, how do you make sure you’re working on the most important stuff? We all know it’s function first – no learning there. But, sorry design engineers, it doesn’t end with function. You must also design for lean, for cost, and factory floor space. Great. More things to design for. Didn’t you say time was short? How the hell am I going to design for all that?

Now onto the seeing business of Axiom 2. If we agree that lean, cost, and factory floor space are the right stuff, we must “see it” if we are to design it out. See lean? See cost? See factory floor space? You’re nuts. How do you expect us to do that?

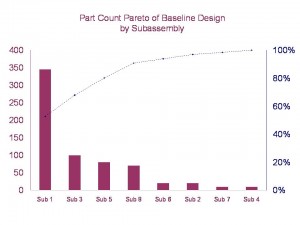

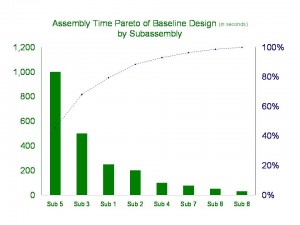

Pareto to the rescue – use Pareto charts to identify the most important stuff, to prioritize the work. With Pareto, it’s simple: work on the biggest bars at the expense of the smaller ones. But, Paretos of what?

There is no such thing as a clean sheet design – all new product designs have a lineage. A new design is based on an existing design, a baseline design, with improvements made in several areas to realize more features or better function defined by the product specification. The Pareto charts are created from the baseline design to allow you to see the things to design out (Axiom 2). But what lenses to use to see lean, cost, and factory floor space?

Here are Pareto’s three lenses so see what must be seen:

To lean out lean out your factory, design out the parts. Parts create waste and part count is the surrogate for lean.

To design out cost, measure cost. Cost is the surrogate for cost.

To design out factory floor space, measure assembly time. Since factory floor space scales with assembly time, assembly time is the surrogate for factory floor space.

Now that your design engineers have created the right Pareto charts and can see with the right glasses, they’re ready to focus their efforts on the most important stuff. No boiling the ocean here. For lean, focus on part count of subassembly 1; for cost, focus on the cost of subassemblies 2 and 4; for floor space, focus on assembly time of subassembly 5. Leave the others alone.

Focus is important and difficult, but Pareto can help you see the light.

DFA and Lean – A Most Powerful One-Two Punch

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

Still not convinced parts are the key? Take a look at the seven wastes and add “of parts” to the end of each one. Here is what it looks like:

- Waste of overproduction (of parts)

- Waste of time on hand – waiting (for parts)

- Waste in transportation (of parts)

- Waste of processing itself (of parts)

- Waste of stock on hand – inventory (of parts)

- Waste of movement (from parts)

- Waste of making defective products (made of parts)

And look at Suzaki’s cartoons. (Click them to enlarge.) What do you see? Parts.

Take out the parts and the waste is not reduced, it’s eliminated. Let’s do a thought experiment, and pretend your product had 50% fewer parts. (I know it’s a stretch.) What would your factory look like? How about your supply chain? There would be: fewer parts to ship, fewer to receive, fewer to move, fewer to store, fewer to handle, fewer opportunities to wait for late parts, and fewer opportunities for incorrect assembly. Loosen your thinking a bit more, and the benefits broaden: fewer suppliers, fewer supplier qualifications, fewer late payments; fewer supplier quality issues, and fewer expensive black belt projects. Most importantly, however, may be the reduction in the transactions, e.g., work in process tracking, labor reporting, material cost tracking, inventory control and valuation, BOMs, routings, backflushing, work orders, and engineering changes.

However, there is a big problem with the thought experiment — there is no one to design out the parts. Since company leadership does not thrust greatness on the design community, design engineers do not have to participate in lean. No one makes them do DFA-driven part count reduction to compliment lean. Don’t think you need the design community? Ask your best manufacturing engineer to write an engineering change to eliminates parts, and see where it goes — nowhere. No design engineer, no design change. No design change, no part elimination.

It’s staggering to think of the savings that would be achieved with the powerful pairing of DFA and lean. It would go like this: The design community would create a low waste design on which the lean community would squeeze out the remaining waste. It’s like the thought experiment; a new product with 50% fewer parts is given to the lean folks, and they lean out the low waste value stream from there. DFA and lean make such a powerful one-two punch because they hit both sides of the waste equation.

DFA eliminates parts, and lean reduces waste from the ones that remain.

There are no technical reasons that prevent DFA and lean from being done together, but there are real failure modes that get in the way. The failure modes are emotional, organizational, and cultural in nature, and are all about people. For example, shared responsibility for design and manufacturing typically resides in the organizational stratosphere – above the VP or Senior VP levels. And because of the failure modes’ nature (organizational, cultural), the countermeasures are largely company-specific.

What’s in the way of your company making the DFA/lean thought experiment a reality?

“Hyper” for Lean

“Hyper” for Lean — Lean Directions, SME

Hypertherm’s lean journey began in 1997 as a natural and enthusiastic extension of its long history of continuous improvement. Founded in 1968, the company’s “lean vision” includes training, application of 5S components, visual factory audits, single and mixed-model flow lines and the engagement of its product design functions.

A recent Hypertherm success is found in the company’s HyPerformance series of plasma arc, metalcutting systems. The company’s product design community designed a product line with Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski