Archive for November, 2011

Organizationally Challenged – Engineering and Manufacturing

Our organizations are set up in silos, and we’re measured that way. (And we wonder why we get local optimization.) At the top of engineering is the VP of the Red Team, who is judged on what it does – product. At the top of manufacturing is the VP of the Blue Team, who is judged on how to make it – process. Red is optimized within Red and same for Blue, sometimes with competing metrics. What we need is Purple behavior.

Here’s a link to a short video (1:14): Organizationally Challenged

And embedded below:

Let me know what you think.

We must broaden “Design”

Design is typically limited to function – what it does – and is done by engineering (red team). Manufacturing is all about how to make it and is done by manufacturing (blue team). Working separately there is local optimization. We must broad to design to include both – red and blue. Working across red-blue boundaries creates magic. This magic can only be done by the purple team.

Below is my first video post. I hope to do more. Let me know what you think.

How To Fix Product Development

The new product development process creates more value than any other process. And because of this it’s a logical target for improvement. But it’s also the most complicated business process. No other process cuts across an organization like new product development. Improvement is difficult.

The new product development process creates more value than any other process. And because of this it’s a logical target for improvement. But it’s also the most complicated business process. No other process cuts across an organization like new product development. Improvement is difficult.

The CEO throws out the challenge – “Fix new product development.” Great idea, but not actionable. Can’t put a plan together. Don’t know the problem. Stepping back, who will lead the charge? Whose problem is it?

The goal of all projects is to solve problems. And it’s no different when fixing product development – work is informed by problems. No problem, no fix. Sure you can put together one hell of a big improvement project, but there’s no value without the right problem. There’s nothing worse than spending lots of time on the wrong problem. And it’s doubly bad with product development because while fixing the wrong problem engineers are not working on the new products. Yikes.

Problems are informed by outcomes. Make a short list of desired outcomes and show the CEO. Your list won’t be right, but it will facilitate a meaningful discussion. Listen to the input, go back and refine the list, and meet again with the CEO. There will be immense pressure to start the improvement work, but resist. Any improvement work done now will be wrong and will create momentum in the wrong direction. Don’t move until outcomes are defined.

With outcomes in hand, get the band back together. You know who they are. You’ve worked with them over the years. They’re influential and seasoned. You trust them and so does the organization. In an off-site location show them the outcomes and ask them for the problems. (To get their best thinking spend money on great food and a relaxing environment.) If they’re the right folks, they’ll say they don’t know. Then, they’ll craft the work to figure it out – to collect and analyze the data. (The first part of problem definition is problem definition.) There will be immense pressure to start the improvement work, but resist. Any work done now will be wrong. Don’t move until problems are defined.

With outcomes and problems in hand, meet with the CEO. Listen. If outcomes change, get the band back together and repeat the previous paragraph. Then set up another meeting with the CEO. Review outcomes and problems. Listen. If there’s agreement, it’s time to put a plan together. If there’s disagreement, stop. Don’t move until there’s agreement. This is where it gets sticky. It’s a battle to balance everyone’s thoughts and feelings, but that’s your challenge. No words of wisdom on than – don’t move until outcomes and problems are defined.

There’s a lot of emotion around the product development process. We argue about the right way to fix it – the right tools, training, and philosophies. But there’s no place for argument. Analyze your process and define outcomes and problems. The result will be a well informed improvement plan and alignment across the company.

Time To Think

We live in a strange time where activity equals progress and thinking does not. Thinking is considered inactivity – wasteful, non-productive, worse than sleeping. (At least napping at your desk recharges the battery.) In today’s world there is little tolerance for thinking.

We live in a strange time where activity equals progress and thinking does not. Thinking is considered inactivity – wasteful, non-productive, worse than sleeping. (At least napping at your desk recharges the battery.) In today’s world there is little tolerance for thinking.

For those that think regularly – or have thought once or twice over the last year – we know thinking is important. If we stop and think, everyone thinks thinking is important. It’s just that we’re too busy to stop and think.

It’s difficult to quantify how bad things are – especially if we’re to compare across industries and continents. Sure it’s easy (and demoralizing) to count the hours spent in meetings or the time spent wasting time with email. But they don’t fully capture a company’s intolerance to thinking. We need a tolerance metric and standardized protocol to measure it.

I’ve invented the Thinking Tolerance Metric, TTM, and a way to measure it. Here’s the protocol: On Monday morning – at your regular start time – find a quiet spot and think. (Your quiet spot can be home, work, a coffee shop, or outside.) No smart phone, no wireless, no meetings. Don’t talk to anyone. Start the clock and start thinking. Think all day.

The clock stops when you receive an email from your boss stating that someone complained about your lack of activity. At the end of the first day, turn on your email and look for the complaint. If it’s there, use the time stamp to calculate TTM using Formula 1:

a

TTM = Time stamp of first complaint – regular start time. [1]

a

If TTM is measured in seconds or minutes, that’s bad. If it’s an hour or two, that’s normal.

If there is no complaint for the entire day, repeat the protocol on day two. Go back to your quiet spot and think. At the end of day two, check for the complaint. Repeat until you get one. Calculate TTM using Formula 1.

Once calculated, send me your data by including it in a comment to this post. I will compile the data and publish it in a follow-on post. (Please remember to include your industry and continent.)

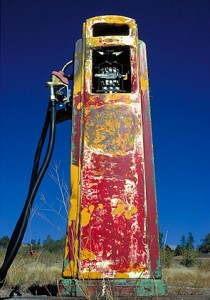

Out Of Gas

You know you’re out of gas when:

You know you’re out of gas when:

- You answer email punctually instead of doing work.

- You trade short term bliss for long term misery.

- You accept an impossible deadline.

- You sit through witless meetings.

- You comply with groupthink.

- You condone bad behavior.

- You placate your boss.

- You write a short post with a bulletized list — because it’s easier.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski