Posts Tagged ‘Creativity’

The Power of Praise

When you catch someone doing good work, do you praise them? If not, why not?

When you catch someone doing good work, do you praise them? If not, why not?

Praise is best when it’s specific – “I think it was great when you [insert specific action here].”

If praise isn’t authentic, it’s not praise.

When you praise specific behavior, you get more of that great behavior. Is there a downside here?

As soon as you see praise-worthy behavior, call it by name. Praise best served warm.

Praise the big stuff in a big way.

Praise is especially powerful when delivered in public.

If praise feels good when you get it, why not help someone else feel good and give it?

If you make a special phone call to deliver praise, that’s a big deal.

If you deliver praise that’s inauthentic, don’t.

Praise the small stuff in a small way.

Outsized praise doesn’t hit the mark like the real deal.

There can be too much praise, but why not take that risk?

If praise was free to give, would you give it? Oh, wait. Praise is free to give. So why don’t you give it?

Praise is powerful, but only if you give it.

Image credit — Llima Orosa

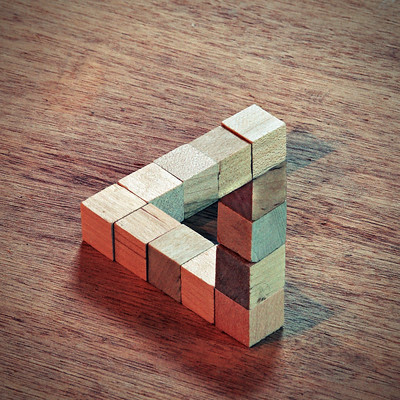

What’s in the way of the newly possible?

When “it’s impossible” it means it “cannot be done.” But maybe “impossible” means “We don’t yet know how to do it.” Or “We don’t yet know if others have done it before.”

When “it’s impossible” it means it “cannot be done.” But maybe “impossible” means “We don’t yet know how to do it.” Or “We don’t yet know if others have done it before.”

What does it take to transition from impossible to newly possible? What must change to move from the impossible to the newly possible?

Context-Specific Impossibility. When something works in one industry or application but doesn’t work in another, it’s impossible in that new context. But usually, almost all the elements of the system are possible and there are one or two elements that don’t work due to the new context. There’s an entire system that’s blocked from possibility due to the interaction between one or two system elements and an environmental element of the new context. The path to the newly possible is found in those tightly-defined interactions. Ask yourself these questions: Which system elements don’t work and what about the environment is preventing the migration to the newly possible? And let the intersection focus your work.

History-Specific Impossibility. When something didn’t work when you tried it a decade ago, it was impossible back then based on the constraints of the day. And until those old constraints are revisited, it is still considered impossible today. Even though there has been a lot of progress over the last decades, if we don’t revisit those constraints we hold onto that old declaration of impossibility. The newly possible can be realized if we search for new developments that break the old constraints. Ask yourself: Why didn’t it work a decade ago? What are the new developments that could overcome those problems? Focus your work on that overlap between the old problems and the new developments.

Emotionally-Specific Impossibility. When you believe something is impossible, it’s impossible. When you believe it’s impossible, you don’t look for solutions that might birth the newly possible. Here’s a rule: If you don’t look for solutions, you won’t find them. Ask yourself: What are the emotions that block me from believing it could be newly possible? What would I have to believe to pursue the newly possible? I think the answer is fear, but not the fear of failure. I think the fear of success is a far likelier suspect. Feel and acknowledge the emotions that block the right work and do the right work. Feel the fear and do the work.

The newly possible is closer than you think. The constraints that block the newly possible are highly localized and highly context-specific. The history that blocks the newly possible is no longer applicable, and it’s time to unlearn it. Discover the recent developments that will break the old constraints. And the emotions that block the newly possible are just that – emotions. Yes, it feels like the fear will kill you, but it only feels like that. Bring your emotions with you as you do the right work and generate the newly possible.

image credit – gfpeck

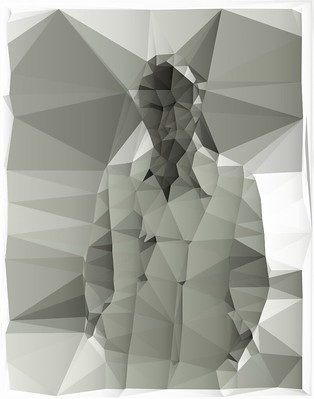

There is always something to build on.

To have something is better than to have nothing, and to focus on everything dilutes progress and leads to nothing. In that way, something can be better than everything.

To have something is better than to have nothing, and to focus on everything dilutes progress and leads to nothing. In that way, something can be better than everything.

What do you have and how might you put it to good use right now?

Everything has a history. What worked last time? What did not? What has changed?

What information do you have that you can use right now? And what’s the first bit of new information you need and what can you to do get it right now?

It is always a brown-field site and never a green-field. You never start from scratch.

What do you have that you can build on right now? How might you use it to springboard into the future?

When it’s time to make a decision, there is always some knowledge about the current situation but the knowledge is always incomplete.

What knowledge do you have right now and how might you use it to advance the cause? What’s the next bit of knowledge you need and why aren’t you trying to acquire that knowledge right now?

You always have your intuition and your best judgment. Those are both real things. They’re not nothing.

How can you use your intuition to make progress right now? How can you use your judgment to advance things right here and right now?

There’s a singular recipe in all this.

Look for what you have (and you always have something) and build on it right now. Then look again and repeat.

Image credit – Jeffrey

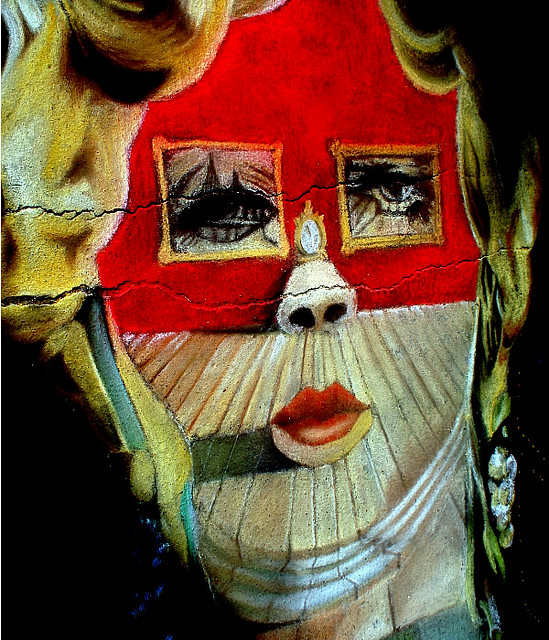

Too Much of a Good Thing

Product cost reduction is a good thing.

Product cost reduction is a good thing.

Too much focus on product cost reduction prevents product enhancements, blocks new customer value propositions, and stifles top-line growth.

Voice of the Customer (VOC) activities are good.

Because customers don’t know what’s possible, too much focus on VOC silences the Voice of the Technology (VOT), blocks new technologies, and prevents novel value propositions. Just because customers aren’t asking for it doesn’t mean they won’t love it when you offer it to them.

Standard work is highly effective and highly productive.

When your whole company is focused on standard work, novelty is squelched, new ideas are scuttled, and new customer value never sees the light of day.

Best practices are highly effective and highly productive.

When your whole company defaults to best practices, novel projects are deselected, risk is radically reduced (which is super risky), people are afraid to try new things and use their judgment, new products are just like the old ones (no sizzle), and top-line growth is gifted to your competitors.

Consensus-based decision-making reduces bad decisions.

In domains of high uncertainty, consensus-based decision-making reduces projects to the lowest common denominator, outlaws the use of judgment and intuition, slows things to a crawl, and makes your most creative people leave the company.

Contrary to Mae West’s maxim, too much of a good thing isn’t always wonderful.

Image credit — Krassy Can Do It

When you say yes to one thing, you say no to another.

Life can get busy and complicated, with too many demands on our time and too little time to get everything done. But why do we accept all the “demands” and why do we think we have to get everything done? If it’s not the most important thing, isn’t a “demand for our time” something less than a demand? And if some things are not all that important, doesn’t it say we don’t have to do everything?

Life can get busy and complicated, with too many demands on our time and too little time to get everything done. But why do we accept all the “demands” and why do we think we have to get everything done? If it’s not the most important thing, isn’t a “demand for our time” something less than a demand? And if some things are not all that important, doesn’t it say we don’t have to do everything?

When life gets busy, it’s difficult to remember it’s our right to choose which things are important enough to take on and which are not. Yes, there are negative consequences of saying no to things, but there are also negative consequences of saying yes. How might we remember the negative consequences of yes?

When you say to yes to one thing, you say no to the opportunity to do something else. Though real, this opportunity cost is mostly invisible. And that’s the problem. If your day is 100% full of meetings, there is no opportunity for you to do something that’s not on your calendar. And in that moment, it’s easy to see the opportunity cost of your previous decisions, but that doesn’t do you any good because the time to see the opportunity cost was when you had the choice between yes and no.

If you say yes because you are worried about what people will think if you say no, doesn’t that say what people think about you is important to you? If you say yes because your physical health will improve (exercise), doesn’t that say your health is important to you? If you say yes to doing the work of two people, doesn’t it say spending time with your family is less important?

Here’s a proposed system to help you. Open your work calendar and move one month into the future. Create a one-hour recurring meeting with yourself. You just created a timeslot where you said no in the future to unimportant things and said yes in the future to important things. Now, make a list of three important things you want to do during those times. And after one month of this, create a second one-hour recurring meeting with yourself. Now you have two hours per week where you can prioritize things that are important to you. Repeat this process until you have allocated four hours per week to do the most important things. You and stop at four hours or keep going. You’ll know when you get the balance right.

And for Saturday and Sunday, book a meeting with yourself where you will do something enjoyable. You can certainly invite family and/or friends, but it the activity must be for pure enjoyment. You can start small with a one-hour event on Saturday and another on Sunday. And, over the weeks, you can increase the number and duration of the meetings.

Saying yes in the future to something important is a skillful way to say no in the future to something less important. And as you use the system, you will become more aware of the opportunity cost that comes from saying yes.

Image credit – Gilles Gonthier

Show Them What’s Possible

When you want to figure out what’s next, show customers what’s possible. This is much different than asking them what they want. So, don’t do that. Instead, show them a physical prototype or a one-page sales tool that explains the value they would realize.

When you want to figure out what’s next, show customers what’s possible. This is much different than asking them what they want. So, don’t do that. Instead, show them a physical prototype or a one-page sales tool that explains the value they would realize.

When they see what’s possible, the world changes for them. They see their work from a new perspective. They see how the unchangeable can change. They see some impossibilities as likely. They see old constraints as new design space. They see the implications of what’s possible from their unique context. And they’re the only ones that can see it. And that’s one of the main points of showing them what’s possible – for YOU to see the implications of what’s possible from their perspective. And the second point is to hear from them what you should have shown them, how you missed the mark, and what you should show them next time.

When you show customers what’s possible, that’s not where things end. It’s where things start.

When you show customers what’s possible, it’s an invitation for them to tell you what it means to them. And it’s also an invitation for you to listen. But listening can be challenging because your context is different than theirs. And because they tell you what they think from their perspective, they cannot be wrong. They might be the wrong customer, or you might have a wrong understanding of their response, but how they see it cannot be wrong. And this can be difficult for the team to embrace.

What you do after learning from the customer is up to you. But there’s one truism – what you do next will be different because of their feedback. I am not saying you should do what they say or build what they ask for. But I think you’ll be money ahead if your path forward is informed by what you learn from the customers.

Image credit — Alexander Henning Drachmann

Rediscovering The Power of Getting Together In-Person

When you spend time with a group in person, you get to know them in ways that can’t be known if you spend time with them using electronic means. When meeting in person, you can tell when someone says something that’s difficult for them. And you can also tell when that difficulty is fake. When using screens, those two situations look the same, but, in person, you know they are different. There’s no way to quantify the value of that type of discernment, but the value borders on pricelessness.

When you spend time with a group in person, you get to know them in ways that can’t be known if you spend time with them using electronic means. When meeting in person, you can tell when someone says something that’s difficult for them. And you can also tell when that difficulty is fake. When using screens, those two situations look the same, but, in person, you know they are different. There’s no way to quantify the value of that type of discernment, but the value borders on pricelessness.

When people know you see them as they really are, they know you care. And they like that because they know your discernment requires significant effort. Sure, at first, they may be uncomfortable because you can see them as they are, but, over time, they learn that your ability to see them as they are is a sign of their importance. And there’s no need to call this out explicitly because all that learning comes as a natural byproduct of meeting in person.

And the game changes when people know you see them (and accept them) for who they are. The breadth of topics that can be discussed becomes almost limitless. Personal stories flow; family experiences bubble to the surface; misunderstandings are discussed openly; vulnerable thoughts and feelings are safely expressed; and trust deepens.

I think we’ve forgotten the power of working together in person, but it only takes three days of in-person project work to help us remember. If you have an important project deliverable, I suggest you organize a three-day, in-person event where a small group gets together to work on the deliverable. Create a formal agenda where it’s 50% work and 50% not work. (I’ve found that the 50% not work is the most valuable and productive.) Make it focused and make it personal. Cook food for the group. Go off-site to a museum. Go for a hike. And work hard. But, most importantly, spend time together.

Things will be different after the three-day event. Sure, you’ll make progress on your project deliverable, but, more importantly, you’ll create the conditions for the group to do amazing work over the next five years.

“Elephants Amboseli” by blieusong is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Free Resources

Since resources are expensive, it can be helpful to see the environment around your product as a source of inexpensive resources that can be modified to perform useful functions. Here are some examples.

Since resources are expensive, it can be helpful to see the environment around your product as a source of inexpensive resources that can be modified to perform useful functions. Here are some examples.

Gravity is a force you can use to do your bidding. Since gravity is always oriented toward the center of the earth, if you change the orientation of an object, you change the direction gravity exerts itself relative to the object. If you flip the object upside down, gravity will push instead of pull.

And it’s the same for buoyancy but in reverse. If you submerge an object of interest in water and add air (bubbles) from below, the bubbles will rise and push in areas where the bubbles collect. If you flip over the object, the bubbles will collect in different areas and push in the opposite direction relative to the object.

And if you have water and bubbles, you have a delivery system. Add a special substance to the air which will collect at the interface between the water and air and the bubbles will deliver it northward.

If you have motion, you also have wind resistance or drag force (but not in deep space). To create more force, increase speed or increase the area that interacts with the moving air. To change the direction of the force relative to the object, change the orientation of the object relative to the direction of motion.

If you have water, you can also have ice. If you need a solid substance look to the water. Flow water over the surface of interest and pull out heat (cool) where you want the ice to form. With this method, you can create a protective coating that can regrow as it gets worn off.

If you have water, you can make ice to create force. Drill a blind hole in a piece of a brittle material (granite), fill the hole with water, and freeze the water by cooling the granite (or leave it outside in the winter). When the water freezes it will expand, push on the granite and break it.

These are some contrived examples, but I hope they help you see a whole new set of free resources you can use to make your magic.

Thank you, VF.

Image credit – audi_insperation

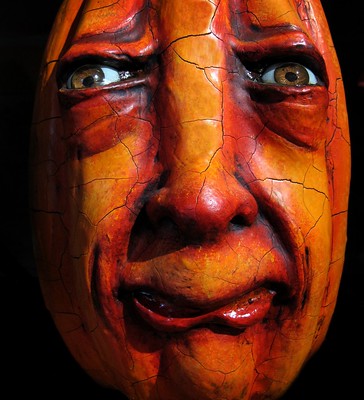

Triangulation of Leadership

Put together things that contradict yet make a wonderfully mismatched pair.

Say things that contradict common misunderstandings.

See the dark and dirty underside of things.

Be more patient with people.

Stomp on success.

Dissent.

Tell the truth even when it’s bad for your career.

See what wasn’t but should have been.

Violate first principles.

Protect people.

Trust.

See things as they aren’t.

See what’s missing.

See yourself.

See.

“man in park (triangulation)” by Josh (broma) is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Work Like You Matter

When you were wrong, the outcome was different than you thought.

When you were wrong, the outcome was different than you thought.

When the outcome was different than you thought, there was uncertainty as the work was new.

When there was uncertainty, you knew there would be learning.

When you were afraid of learning, you were afraid to be wrong.

And when you were afraid to be wrong, you were really afraid about what people would think of you.

Would you rather wall off uncertainty to prevent yourself from being wrong or would you rather try something new?

If there’s a difference between what others think of you and what you think of yourself, whose opinion matters more?

Why does it matter what people think of you?

Why do you let their mattering block you from trying new things?

In the end, hold onto the fact that you matter, especially when you have the courage to be wrong.

“Oh no, what went wrong?” by Bennilover is marked with CC BY-ND 2.0.

Three Things for the New Year

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Some things will be the same and some will be different. The trouble is that we won’t know which is which until we do. We can speculate on how it will be different, but the Universe doesn’t care about our speculation. Sure, it can be helpful to think about how things may go, but as long as we hold on to the may-ness of our speculations. And we don’t know when we’ll know. We’ll know when we know, but no sooner. Even when the Operating Plan declares the hardest of hard dates, the Universe sets the learning schedule on its own terms, and it doesn’t care about our arbitrary timelines.

What to do?

Step 1. Try three new things. Choose things that are interesting and try them. Try to try them in parallel as they may interact and inform each other. Before you start, define what success looks like and what you’ll do if they’re successful and if they’re not. Defining the follow-on actions will help you keep the scope small. For things that work out, you’ll struggle to allocate resources for the next stages, so start small. And if things don’t work out, you’ll want to say that the projects consumed little resources and learned a lot. Keep things small. And if that doesn’t work, keep them smaller.

Step 2. Rinse and repeat.

I wish you a happy and safe New Year. And thanks for reading.

Mike

“three” by Travelways.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski