Posts Tagged ‘Cost Savings’

How I Develop Engineering Leaders

For the past two decades, I’ve actively developed engineering leaders. A good friend asked me how I do it, so I took some time to write it down. Here is the curriculum in the form of How Tos:

For the past two decades, I’ve actively developed engineering leaders. A good friend asked me how I do it, so I took some time to write it down. Here is the curriculum in the form of How Tos:

How to build trust. This is the first thing. Always. Done right, the trust-based informal networks are stronger than the formal organization chart. Done right, the informal networks can protect the company from bad decisions. Done right, the right information flows among the right engineers at the right time so the right work happens in the right way.

How to decide what to do next. This is a broad one. We start with a series of questions: What are we doing now? What’s the problem? How do you know? What should we do more of? What should we do less of? What resources are available? When must we be done?

How to map the current state. We don’t define the idealized future state or the North Star, we start with what’s happening now. We make one-page maps of the territory. We use drawings, flow charts, boxes/arrows, and the fewest words. And we take no action before there’s agreement on how things are. The value of GPS isn’t to define your destination, it’s to establish your location. That’s why we map the current state.

How to build momentum. It’s easy to jump onto a moving steam train, but a stationary one is difficult to get moving. We define the active projects and ask – How might we hitch our wagon to a fast-moving train?

How to start something new. We start small and make a thought-provoking demo. The prototype forces us to think through all the elements, makes things real, and helps others understand the concept. If that doesn’t work, we start smaller.

How to define problems so we can solve them easily. We define problems with blocks and arrows, and limit ourselves to one page. The problem is defined as a region of contact between two things, and we identify it with the color red. That helps us know where the problem is and when it occurs. If there are two problems on a page, we break it up into two pages with one problem. Then we decide to solve the problem before, during, or after it occurs.

How to design products that work better and cost less. We create Pareto charts of the cost of the existing product (cost by subassembly and cost by part) and set a cost reduction goal. We create Pareto charts of the part count of the existing product (part count by subassembly and part count by individual part number) and define a goal for part count reduction. We define test protocols that capture the functionality customers care about. We test the existing product and set performance improvement goals for the new one. We test the new product using the same protocols and show the data in a simple A-B format. We present all this data at formal design reviews.

How to define technology projects. We define how the customer does their work. We then define the evolutionary history of our products and services, and project that history forward. For lines of goodness with trajectories that predict improvement, we run projects to improve them. For lines of goodness with stalled trajectories, we run projects to establish new technologies and jump to the next S-curve. We assess our offerings for completeness and create technologies to fill the gap.

How to file the right patents. We ask these questions: How quickly will the customer notice the new functionality or benefit? Once recognized, will they care? Will the patent protect high-volume / high-margin consumables? There are more questions, but these are the ones we start with. And the patent team is an integral part of the technology reviews and product development process.

How to do the learning. We start with the leader’s existing goals and deliverables and identify the necessary How Tos to get their work done. There are no special projects or extra work.

If you’re interested in learning more about the curriculum or how to enroll, send me an email mike@shipulski.com.

Image credit — Paul VanDerWerf

Product Thinking

Product costs, without product thinking, drop 2% per year. With product thinking, product costs fall by 50%, and while your competitors’ profit margins drift downward, yours are too high to track by conventional methods. And your company is known for unending increases in stock price and long term investment in all the things that secure the future.

The supply chain, without product thinking, improves 3% per year. With product thinking, longest lead processes are eliminated, poorest yield processes are a thing of the past, problem suppliers are gone, and your distributers associate your brand with uninterrupted supply and on time delivery.

Product robustness, without product thinking, is the same year-on-year. Re-injecting long forgotten product thinking to simplify the product, product robustness jumps to unattainable levels and warranty costs plummet. And your brand is known for products that simply don’t break.

Rolled throughput yield is stalled at 90%. With product thinking, the product is simplified, opportunities for defects are reduced, and throughput skyrockets due to improved RTY. And your brand is known as a good value – providing good, repeatable functionality at a good price.

Lean, without product thinking has delivered wonderful results, but the low hanging fruit is gone and lean is moving into the back office. With product thinking, the design is changed and value-added work is eliminated along with its associated non-value added work (which is about 8 times bigger); manufacturing monuments with their long changeover times are ripped out and sold to your competitors; work from two factories is consolidated into one; new work is taken on to fill the emptied factories; and profit per square foot triples. And your brand is known for best-in-class quality, unbeatable on time delivery, world class performance, and pioneering the next generation of lean.

The sales argument is low price and good payment terms. With product thinking, the argument starts with product performance and ends with product reliability. The sales team is energized, and your brand is linked with solid products that just plain work.

The marketing approach is stickers and new packaging. With product thinking, it’s based on competitive advantage explained in terms of head-to-head performance data and a richer feature set. And your brand stands for winning technology and killer products.

Product thinking isn’t for everyone. But for those that try – your brand will thank you.

Your product costs are twice what they should be.

Your product costs are twice what they should be. That’s right. Twice.

Your product costs are twice what they should be. That’s right. Twice.

You don’t believe me. But why? Here’s why:

If 50% cost reduction is possible, that would mean you’ve left a whole shitpot of money on the table year-on-year and that would be embarrassing. But for that kind of money don’t you think you could work through it?

If 50% cost reduction is possible, a successful company like yours would have already done it. No. In fact, it’s your success that’s in the way. It’s your success that’s kept you from looking critically at your product costs. It’s your success that’s allowed you to avoid the hard work of helping the design engineering community change its thinking. But for that kind of money don’t you think you could work through it?

Even if you don’t believe 50% cost reduction is possible, for that kind of money don’t you think it’s worth a try?

Don’t bankrupt your suppliers – get Design Engineers involved.

Cost Out, Cost Down, Cost Reduction, Should Costing – you’ve heard about these programs. But they’re not what they seem. Under the guise of reducing product costs they steal profit margin from suppliers. The customer company increases quarterly profits while the supplier company loses profits and goes bankrupt. I don’t like this. Not only is this irresponsible behavior, it’s bad business. The savings are less than the cost of qualifying a new supplier. Shortsighted. Stupid.

Cost Out, Cost Down, Cost Reduction, Should Costing – you’ve heard about these programs. But they’re not what they seem. Under the guise of reducing product costs they steal profit margin from suppliers. The customer company increases quarterly profits while the supplier company loses profits and goes bankrupt. I don’t like this. Not only is this irresponsible behavior, it’s bad business. The savings are less than the cost of qualifying a new supplier. Shortsighted. Stupid.

The real way to do it is to design out product cost, to reduce the cost signature. Margin is created and shared with suppliers. Suppliers make more money when it’s done right. That’s right, I said more money. More dollars per part, and not more from the promise of increased sales. (Suppliers know that’s bullshit just as well as you, and you lose credibility when you use that line.) The Design Engineering community are the only folks that can pull this off.

Only the Design Engineers can eliminate features that create cost while retaining features that control function. More function, less cost. More margin for all. The trick: how to get Design Engineers involved.

There is a belief that Design Engineers want nothing to do with cost. Not true. Design Engineers would love to design out cost, but our organization doesn’t let us, nor do they expect us to. Too busy; too many products to launch; designing out cost takes too long. Too busy to save 25% of your material cost? Really? Run the numbers – material cost times volume times 25%. Takes too long? No, it’s actually faster. Manufacturing issues are designed out so the product hits the floor in full stride so Design Engineers can actually move onto designing the next product. (No one believes this.)

Truth is Design Engineers would love to design products with low cost signatures, but we don’t know how. It’s not that it’s difficult, it’s that no one ever taught us. What the Design Engineers need is an investment in the four Ts – tools, training, time, and a teacher.

Run the numbers. It’s worth the investment.

Material cost x Volume x 25%

DFA and Lean – A Most Powerful One-Two Punch

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

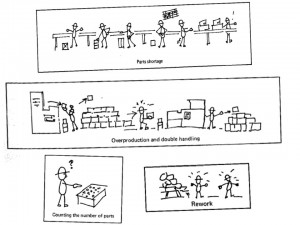

Still not convinced parts are the key? Take a look at the seven wastes and add “of parts” to the end of each one. Here is what it looks like:

- Waste of overproduction (of parts)

- Waste of time on hand – waiting (for parts)

- Waste in transportation (of parts)

- Waste of processing itself (of parts)

- Waste of stock on hand – inventory (of parts)

- Waste of movement (from parts)

- Waste of making defective products (made of parts)

And look at Suzaki’s cartoons. (Click them to enlarge.) What do you see? Parts.

Take out the parts and the waste is not reduced, it’s eliminated. Let’s do a thought experiment, and pretend your product had 50% fewer parts. (I know it’s a stretch.) What would your factory look like? How about your supply chain? There would be: fewer parts to ship, fewer to receive, fewer to move, fewer to store, fewer to handle, fewer opportunities to wait for late parts, and fewer opportunities for incorrect assembly. Loosen your thinking a bit more, and the benefits broaden: fewer suppliers, fewer supplier qualifications, fewer late payments; fewer supplier quality issues, and fewer expensive black belt projects. Most importantly, however, may be the reduction in the transactions, e.g., work in process tracking, labor reporting, material cost tracking, inventory control and valuation, BOMs, routings, backflushing, work orders, and engineering changes.

However, there is a big problem with the thought experiment — there is no one to design out the parts. Since company leadership does not thrust greatness on the design community, design engineers do not have to participate in lean. No one makes them do DFA-driven part count reduction to compliment lean. Don’t think you need the design community? Ask your best manufacturing engineer to write an engineering change to eliminates parts, and see where it goes — nowhere. No design engineer, no design change. No design change, no part elimination.

It’s staggering to think of the savings that would be achieved with the powerful pairing of DFA and lean. It would go like this: The design community would create a low waste design on which the lean community would squeeze out the remaining waste. It’s like the thought experiment; a new product with 50% fewer parts is given to the lean folks, and they lean out the low waste value stream from there. DFA and lean make such a powerful one-two punch because they hit both sides of the waste equation.

DFA eliminates parts, and lean reduces waste from the ones that remain.

There are no technical reasons that prevent DFA and lean from being done together, but there are real failure modes that get in the way. The failure modes are emotional, organizational, and cultural in nature, and are all about people. For example, shared responsibility for design and manufacturing typically resides in the organizational stratosphere – above the VP or Senior VP levels. And because of the failure modes’ nature (organizational, cultural), the countermeasures are largely company-specific.

What’s in the way of your company making the DFA/lean thought experiment a reality?

Measuring DFMA Savings

Wes Iverson, Managing Editor of Automation World, wrote a good artcle on DFMA’s ability to cut product cost, reduce part count, and save assembly floor space.

Measuring DFMA Savings — Automation World

An expert from his article:

When a Hypertherm team led by Shipulski designed a major new plasma cutting machine several years ago, the team was able to reduce the number of parts required to about 700, down from around 1,400 in the previous generation design. The result was a machine that took about four hours to build, compared to 10 hours for the previous unit, enabling Hypertherm to hit its 35 percent cost reduction target for the system.

Redesigns get radical improvements using DFMA

Redesigns get radical improvements using DFMA

Hypertherm, Inc. of Hanover, NH, is among the world’s foremost manufacturers of plasma arc cutting equipment. Founded in 1968 with a staff of two, the company today has 750 employees, with subsidiaries, sales offices, and distributors in multiple countries. All technology development, product development, and manufacturing is done in the Hanover area.

View of the new HyPerformance Plasma HPR130 plasma cutter from Hypertherm. The company used Design for Manufacture and Analysis (DFMA) methodology to radically redesign — and improve — the system’s manufacturability. In the new plasma cutter, system subassemblies took 45% to 89% less time to put together. Assembly floor space opened up by 40%. Warranty cost went down 83%. Cost savings amounted to $5 million over 24 months, which helped the company achieve record earnings and its highest profit sharing on record.

Hypertherm’s products range from lightweight, manual plasma cutting equipment to highly mechanized systems that operate with CNC cutting machines. Its advanced technology serves a global customer base in every industry that depends on quality and reliability in high-temperature metal cutting, such as shipbuilding, construction, farm equipment, rail car and truck manufacture, and plant maintenance.

Recently, Hypertherm engineers tackled a project of mammoth proportions when they remodeled the company’s highly successful HD3070 plasma cutting system — and ultimately created the new HyPerformance Plasma HPR130 plasma cutter. Before the redesign project, the HD3070 sold well and was widely regarded as a standard for robust, high-precision cutting in the industry. Hypertherm wanted to make the product even better.

“We started with a vision to make a radical improvement in product performance coupled with a radical reduction in product cost,” says Mike Shipulski, director of engineering for Hypertherm. He believed that using the methodology of Design for Manufacture and Analysis (DFMA) would help identify unnecessary parts, highlight assembly difficulties that Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski