Archive for August, 2018

How To Design

What do they want? Some get there with jobs-to-be-done, some use Customer Needs, some swear by ethnographic research and some like to understand why before what. But in all cases, it starts with the customer. Whichever mechanism you use, the objective is clear – to understand what they need. Because if you don’t know what they need, you can’t give it to them. And once you get your arms around their needs, you’re ready to translate them into a set of functional requirements, that once satisfied, will give them what they need.

What do they want? Some get there with jobs-to-be-done, some use Customer Needs, some swear by ethnographic research and some like to understand why before what. But in all cases, it starts with the customer. Whichever mechanism you use, the objective is clear – to understand what they need. Because if you don’t know what they need, you can’t give it to them. And once you get your arms around their needs, you’re ready to translate them into a set of functional requirements, that once satisfied, will give them what they need.

What does it do? A complete set of functional requirements is difficult to create, so don’t start with a complete set. Use your new knowledge of the top customer needs to define and prioritize the top functional requirements (think three to five). Once tightly formalized, these requirements will guide the more detailed work that follows. The functional requirements are mapped to elements of the design, or design parameters, that will bring the functions to life. But before that, ask yourself if a check-in with some potential customers is warranted. Sometimes it is, but at these early stages it’s may best to wait until you have something tangible to show customers.

What does it look like? The design parameters define the physical elements of the design that ultimately create the functionality customers will buy. The design parameters define shape of the physical elements, the materials they’re made from and the interaction of the elements. It’s best if one design parameter controls a single functional requirement so the functions can be dialed in independently. At this early concept phase, a sketch or CAD model can be created and reviewed with customers. You may learn you’re off track or you may learn you’re way off track, but either way, you’ll learn how the design must change. But before that, take a little time to think through how the product will be made.

How to make it? The process variables define the elements of the manufacturing process that make the right shapes from the right materials. Sometimes the elements of the design (design parameters) fit the process variables nicely, but often the design parameters must be changed or rearranged to fit the process. Postpone this mapping at your peril! Once you show a customer a concept, some design parameters are locked down, and if those elements of the design don’t fit the process you’ll be stuck with high costs and defects.

How to sell it? The goodness of the design must be translated into language that fits the customer. Create a single page sales tool that describes their needs and how the new functionality satisfies them. And include a digital image of the concept and add it to the one-pager. Show document to the customer and listen. The customer feedback will cause you to revisit the functional requirements, design parameters and process variables. And that’s how it’s supposed to go.

Though I described this process in a linear way, nothing about this process is linear. Because the domains are mapped to each other, changes in one domain ripple through the others. Change a material and the functionality changes and so do the process variables needed to make it. Change the process and the shapes must change which, in turn, change the functionality.

But changes to the customer needs are far more problematic, if not cataclysmic. Change the customer needs and all the domains change. All of them. And the domains don’t change subtly, they get flipped on their heads. A change to a customer need is an avalanche that sweeps away much of the work that’s been done to date. With a change to a customer need, new functions must be created from scratch and old design elements must culled. And no one knows what the what the new shapes will be or how to make them.

You can’t hold off on the design work until all the customer needs are locked down. You’ve got to start with partial knowledge. But, you can check in regularly with customers and show them early designs. And you can even show them concept sketches.

And when they give you feedback, listen.

Image credit – Worcester Wired

To figure out what’s next, define the system as it is.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every morning your day starts with the body you have. You may have had a more pleasing body in the past, but that’s gone. You may have visions of changing your body into something else, but you don’t have that yet. What you do today is governed and enabled by your body as it is. If you try to lift three hundred pounds, your system as it is will either pick it up or it won’t.

Every morning your day starts with the mind you have. It may have been busy and distracted in the past and it may be calm and settled in the future, but that doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is your mind as it is. If you respond kindly, today’s mind is responsible, and if your response is unkind, today’s mind system is the culprit. Like it or not, your thoughts, feelings and actions are the result of your mind as it is.

Change always starts with where you are, and the first step is unclear until you assess and define your systems as they are. If you haven’t worked out in five years, your first step is to see your doctor to get clearance (professional assessment) for your upcoming physical improvement plan. If you’ve run ten marathons over the last ten months, your first step may be to take a month off to recover. The right next step starts with where you are.

And it’s the same with your mind. If your mind is all over the place your likely first step is to learn how to help it settle down. And once it’s a little more settled, your next step may be to use more advanced methods to settle it further. And if you assess your mind and you see it needs more help than you can give it, your next step is to seek professional help. Again, your next step is defined by where you are.

And it’s the same with business. Every morning starts with the products and services you have. You can’t sell the obsolete products you had, nor can you sell the future services you may develop. You can only sell what you have. But, in parallel, you can create the next product or system. And to do that, the first step is to take a deep, dispassionate look at the system as it is. What does it do well? What does it do poorly? What can be built on and what can be discarded? There are a number of tools for this, but more important than the tools is to recognize that the next one starts with an assessment of the one you have.

If the existing system is young and immature, the first step is likely to nurture it and support it so it can grow out of its adolescence. But the first step is NOT to lift three hundred pounds because the system-as it is-can only lift fifty. If you lift too much too early, you’ll break its back.

If the existing system is in it’s prime and has been going to the gym regularly for the last five years, its ready for three hundred pounds. Go for it! But, in parallel, it’s time to start a new activity, one that will replace the weightlifting when the system can no longer lift like it used to. Maybe tennis? But start now because to get good at tennis requires new muscles and time.

And if the existing system is ready for retirement, retire it. Difficult to do, but once there’s public acknowledgement, the retirement will take care of itself.

If you want to know what’s next, define the system as it is. The next step will be clear.

And the best time to do it is now.

Image credit – NASA

The Importance of Helping Others

When someone you care about needs help, help them. Even when you have other things to do, help them anyway.

When someone you care about needs help, help them. Even when you have other things to do, help them anyway.

When people ask you for help, it’s a sign they trust you. And they trust you because you’ve demonstrated over time that your words and behaviors match. You said you’d do A and you did A. You said you’d do B and you did B. And because you’ve made that investment in them over the years, they value you and your time. And because they value you and your time, they don’t want to be a burden to you. And if they think you’ve got a lot on your plate, they may downplay the importance of their need for help and say things like “It’s no big deal.” or “It’s not that important.” or “It’s okay, it can wait.”.

However unforcefully, they asked for help because the need it. It was a big deal for them to ask because they know you are busy. And their willingness to dismiss or delay, is not a sign of unimportance of their need. Rather, it’s a show of their respect for you and your time. They desperately need your help, but care enough about you to give you any opportunity to say no. Those are the telltale signs that it’s time to stop what you’re doing and help them. This is the time when you can make the biggest difference. Stop immediately and help them.

Your helping starts with listening and listening starts with getting ready to listen. Smile and tell them that this little chat deserves a coffee or cold drink and walk with them to get a beverage. This critical step serves several functions. It makes it clear you are willing to make time for them and puts them at ease; it gives you time to let go of what you were working on so you can give them your full attention; and it gives you a little time to put yourself in their shoes so you will be able to hear what really going on.

By making time for them, you’ve already helped them. Someone they trust and respect stopped what they were doing and made time for them. They’re already standing two inches taller. And, with a clear head, you actively listen and understand, they grow another two inches. Often, just telling their story is enough for them to solve their own problem. In that way, your helping starts and ends with listening. And other times, they don’t really want you to solve their problem, they just want you to listen and empathize. And when they’re looking for more, rather than giving them answers, they’d rather you ask clarifying questions and paraphrase to demonstrate understanding.

You can’t do this for everyone, but you can do it for the people you care about most. Sure, you have to scamper to catch up on your own work, but it’s worth it. By helping them you help yourself twice – once from happiness that comes from helping someone you care about and twice from the joy that comes from watching them do the same for people they care about.

Our work is difficult and our lives are busy. But our work gets easier when we get and give help. And even with our always-on, always-connected culture, life is about building meaningful connections. How can your life be too busy for that?

Maybe we have it backwards. What if meaningful connections aren’t something we create so we can do our work better? What if we think of work as nothing more than a mechanism to create meaningful connections?

Image credit – Jlhopgood.

The right time horizon for technology development

Patents are the currency of technology and profits are the currency of business. And as it turns out, if you focus on creating technology you’ll get technology (and patents) and if you focus on profits you’ll get profits. But if no one buys your technology (in the form of the products or services that use it), you’ll go out of business. And if you focus exclusively on profits you won’t create technology and you’ll go out of business. I’m not sure which path is faster or more dangerous, but I don’t think it matters because either way you’re out of business.

Patents are the currency of technology and profits are the currency of business. And as it turns out, if you focus on creating technology you’ll get technology (and patents) and if you focus on profits you’ll get profits. But if no one buys your technology (in the form of the products or services that use it), you’ll go out of business. And if you focus exclusively on profits you won’t create technology and you’ll go out of business. I’m not sure which path is faster or more dangerous, but I don’t think it matters because either way you’re out of business.

It’s easy to measure the number of patents and easier to measure profits. But there’s a problem. Not all patents (technologies) are equal and not all profits are equal. You can have a stockpile of low-level patents that make small improvements to existing products/services and you can have a stockpile of profits generated by short-term business practices, both of which are far less valuable than they appear. If you measure the number of patents without evaluating the level of inventiveness, you’re running your business without a true understanding of how things really are. And if you’re looking at the pile of profits without evaluating the long-term viability of the engine that created them you’re likely living beyond your means.

In both cases, it’s important to be aware of your time horizon. You can create incremental technologies that create short term wins and consume all your resource so you can’t work on the longer-term technologies that reinvent your industry. And you can implement business practices that eliminate costs and squeeze customers for next-quarter sales at the expense of building trust-based engines of growth. It’s all about opportunity cost.

It’s easy to develop technologies and implement business processes for the short term. And it’s equally easy to invest in the long term at the expense of today’s bottom line and payroll. The trick is to balance short against long.

And for patents, to achieve the right balance rate your patents on the level of inventiveness.

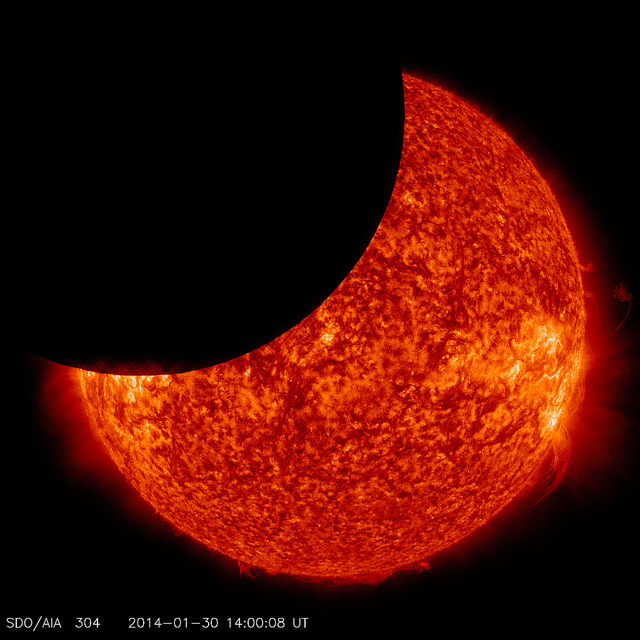

Image credit – NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory

How mature is your technology?

As a technologist it’s important to know the maturity of a technology. Like people, technologies are born, they become children, then adolescents, then adults and then they die. And like with people, the character and behavior of technologies change as they grown and age. A fledgling technology may have a lot of potential, but it can’t pay the mortgage until it matures. To know a technologies level of maturity is to know when it’s premature to invest, to know when it’s time to invest, to know when to ride it for all it’s worth and time to let it go.

As a technologist it’s important to know the maturity of a technology. Like people, technologies are born, they become children, then adolescents, then adults and then they die. And like with people, the character and behavior of technologies change as they grown and age. A fledgling technology may have a lot of potential, but it can’t pay the mortgage until it matures. To know a technologies level of maturity is to know when it’s premature to invest, to know when it’s time to invest, to know when to ride it for all it’s worth and time to let it go.

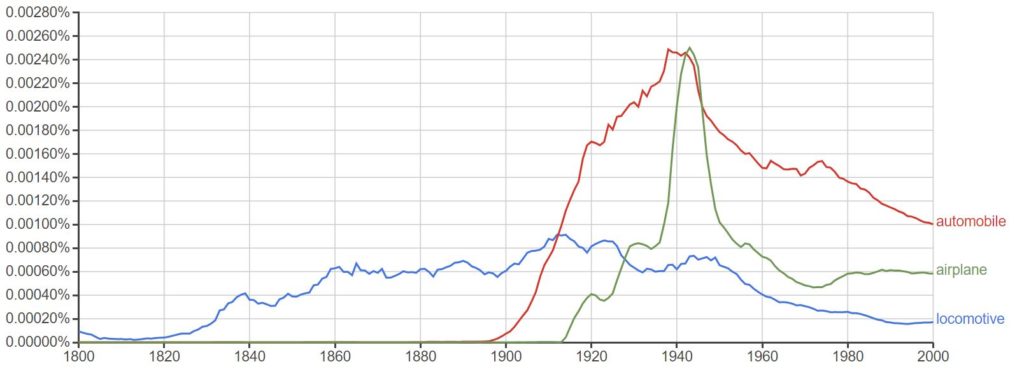

Google has a tool called Ngram Viewer that performs keyword searches of a vast library of books and returns a plot of how frequently the word was found in the books. Just type the word in the search line, specify the years (1800-2007) and look at the graph.

Below is a graph I created for three words: locomotive, automobile and airplane. (Link to graph.) If each word is assumed to represent a technology, the graph makes it clear when authors started to write about the technologies (left is earliest) and how frequently it was used (taller is more prevalent). As a technology, locomotives came first, as they were mentioned in books as early as 1800. Next came the automobile which hit the books just before 1900. And then came the airplane which first showed itself in about 1915.

In the 1820s the locomotives were infants. They were slow, inefficient and unreliable. But over time they matured and replaced the Pony Express. In the late 1890s the automobiles were also infants and also slow, inefficient and unreliable. But as they matured, they displaced some of the locomotives. And the airplanes of 1915 were unsafe and barely flight-worthy. But over time they matured and displaced the automobiles for the longest trips.

[Side note – the blip in use of the word in 1940s is probably linked to World War II.]

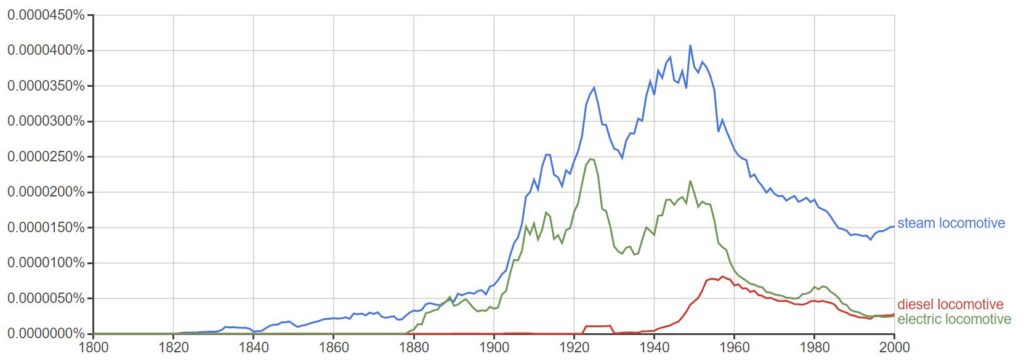

But for the locomotive, there’s a story with a story. Below is a graph I created for: steam locomotive, diesel locomotive and electric locomotive. After it matured in the 1840s and became faster and more efficient, the steam locomotive displaced the wagon trains. But, as technology likes to do, the electric locomotive matured several decades after it’s birth in 1880 and displaced it’s technological parent the steam locomotive. There was no smoke with the electric locomotive (city applications) and it did not need to stop to replenish it’s coal and water. And then, because turn-about is fair play, the diesel locomotive displaced some of the electric locomotives.

The Ngram Viewer tool isn’t used for technology development because books are published long after the initial technology development is completed and there is no data after 20o7. But, it provides a good example of how new technologies emerge in society and how they grow and displace each other.

To assess the maturity of the youngest technologies, technologists perform similar time-based analyses but on different data sets. Specialized tools are used to make similar graphs for patents, where infant technologies become public when they’re disclosed in the form of patents. Also, special tools are used to analyze the prevalence of keywords (i.e., locomotives) for scientific publications. The analysis is similar to the Ngram Viewer analysis, but the scientific publications describe the new technologies much sooner after their birth.

To know the maturity of the technology is to know when a technology has legs and when it’s time to invent it’s replacement. There’s nothing worse than trying to improve a mature technology like the diesel locomotive when you should be inventing the next generation Maglev train.

Image credit – kanegen

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski