Archive for the ‘Business Model’ Category

How To Put The Business Universe On One Page

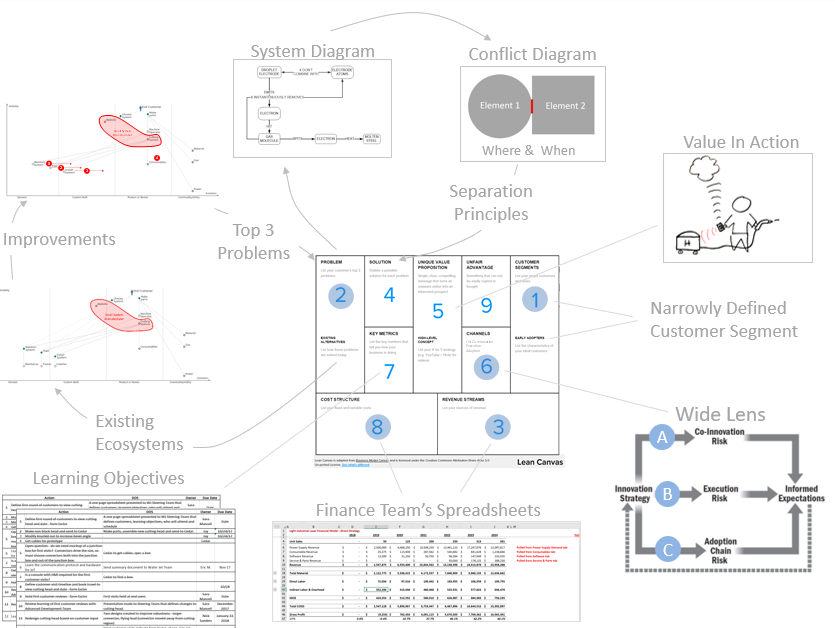

When I want to understand a large system, I make a map. If the system is an ecosystem, I combine Wardley Maps by Simon Wardley with Wide Lens / Winning The Right Game by Ron Adner. On Wardley maps, activities and actors are placed on the map, and related elements are connected. On the left are infant and underdeveloped elements, and on the right are fully developed / commodity elements. It’s like an S-curve that’s been squished flat.

When I want to understand a large system, I make a map. If the system is an ecosystem, I combine Wardley Maps by Simon Wardley with Wide Lens / Winning The Right Game by Ron Adner. On Wardley maps, activities and actors are placed on the map, and related elements are connected. On the left are infant and underdeveloped elements, and on the right are fully developed / commodity elements. It’s like an S-curve that’s been squished flat.

Wide Lens prompts you to consider co-innovation (who needs to innovate for you to be successful) and adoption (who needs to believe your idea is a good one). Winning The Right Game makes you think through the sequence of attracting partners like a visual time-lapse of the ecosystem’s evolution. This is a killer combination that demands you put the whole system on one page – all the players/partners, all the activities sorted by maturity, all the interactions, and the evolution of the partner network and maturity of the system elements. This forces a common understanding of the ecosystem. There’s no way out. Did I say it must fit on one page?

When the large system is a technological system, I make a map. I use the best TRIZ book (Innovation On Demand) by Victor Fey. A functional analysis is performed on the system using noun-verb pairs that are strung together to represent how the system behaves. If you want to drive people crazy, this is the process for you. It requires precise words for each noun (element) and verb (action) pair, and the pairs must hang together in a way that represents the physical system. There can be only one description of the system, and the fun and games don’t stop until the team converges on a single representation of the system. It’s all good fun until someone loses an eye.

When I want to understand a business/technology/product/service offering that has not been done before (think startup), I use Lean Canvas by Ash Maurya. The Lean Canvas requires you to think through all elements of the system and forces you to put it on one page. (Do you see a theme here?) Value proposition, existing alternatives, channel to market, customer segments, metrics, revenue, costs, problems, and solutions – all of them on one page.

And then to blow people’s minds, I combine Wardley Maps, Wide Lens, Winning The Right Game, functional analysis of TRIZ, value in action, and Lean Canvas on one page. And this is what it looks like.

Ash’s Lean Canvas is the backplane. Ron’s Wide Lens supports 6 (Channel), forcing a broader look than a traditional channel view. Ron’s Winning The Right Game and Simon’s Wardley Map are smashed together to support 2 (Existing Alternatives/Problems). A map is created for the existing system with system elements (infants on the left, retirees on the right) and partners/players, which are signified by color (red blob). Then, a second map is created to define the improvements to be made (red circles with arrows toward a more mature state). Victor’s Functional Analysis/System diagram defines the problematic system, and TRIZ tools, e.g., Separation Principles, are used to solve the problem.

When I want to understand a system (ecosystem or technological system), I make a map. And when I want to make a good map, I put it on one page. And when I want to create a new technological system that’s nested in a new business model that’s nested in a new ecosystem, I force myself to put the whole universe on one page.

Image credit – Giuseppe Zeta

Partners can be more important than product when selling into new applications.

We all want to increase top-line revenue by selling more. But we’ve been selling our existing products into the same old applications for a long time now, and we’ve reached a hard limit – when we add more effort, we get little in return. Developing an entirely new product will take a long time, so we will try to sell our existing products into new applications. We will have to change our product slightly to make it work in the new applications, but we can do that quickly. We have a good plan.

We search the globe for these new applications and find a winner. It’s a new application in which our product has a technological advantage over the existing products. The new value is clear to the customer, and they want to get rid of their existing products and replace them with our flagship product. Our product requires minimal changes, which we’ve already implemented. Our product is ready to sell! Let’s go! Let’s get after it. Not so fast.

As it turns out, the customers don’t know how to use our product, they don’t know how to install it, and they don’t have a way to buy the consumables and maintenance parts. Before we can sell, we must figure out a way to get the products installed, to train the operators, to find a way to sell the wear parts and consumables, and to service the product. As it turns out, with this new application, there are a lot of missing elements to the go-to-market system.

When selling into new applications, it’s not all about the product. It’s all about the partners. It’s about finding and developing partners familiar with the industry, the application, and the customers. But it’s tricky. You are unfamiliar with the application and don’t know how to find these partners. Once you identify them, they are unfamiliar with your product, how it’s installed, how it’s operated, and how it’s serviced.

It takes time and effort to educate, train, and develop a new partner. They may know the customer, but they don’t know the ins and outs of your product. And they need to educate, train, and develop you. You may know your product, but you don’t know the customers and the ins and outs of the application.

These new applications can create incremental revenue for you and your new partners, and that’s exciting. But at the early stages of development, these new applications require more time and investment than we’re used to. The profitability equation will take some time to realize its full potential. And to realize that full potential, be sure to create a go-to-market model that is profitable for your partner. An unprofitable partner can’t afford to be a good partner. And you need good partners.

Image credit — TMAB2003

The Next Evolution of Your Success

New ways to work are new because they have not been done before.

New ways to work are new because they have not been done before.

How many new ways to work have you demonstrated over the last year?

New customer value is new when it has not been shown before.

What new customer value have you demonstrated over the last year?

New ways to deliver customer value are new when you have not done it that way before.

How much customer value have you demonstrated through non-product solutions?

The success of old ways of working block new ways.

How many new ways to work have been blocked by your success?

The success of old customer value blocks new customer value.

How much new customer value has been blocked by your success with old customer value?

The success of tried and true ways to deliver customer value blocks new ways to deliver customer value.

Which new ways to deliver unique customer value have been blocked by your success?

Might you be more successful if you stop blocking yourself with your success?

How might you put your success behind you and create the next evolution of your success?

Image credit — Andy Morffew

Is the timing right?

If there is no problem, it is too soon for a solution.

If there is no problem, it is too soon for a solution.

But when there is consensus on a problem, it may be too late to solve it.

If a powerful protector of the Status Quo is to retire in a year, it may be too early to start work on the most important sacrilege.

But if the sacrilege can be done under cover, it may be time to start.

It may be too soon to put a young but talented person in a leadership position if the team is also green.

But it may be the right time to pair the younger person with a seasoned leader and move them both to the team.

When the business model is highly profitable, it may be too soon to demonstrate a more profitable business model that could obsolete the existing one.

But new business models take a long time to gestate and all business models have half-lives, so it may be time to demonstrate the new one.

If there is no budget for a project, it is too soon for the project.

But the budget may never come, so it is probably time to start the project on the smallest scale.

When the new technology becomes highly profitable, it may be too soon to demonstrate the new technology that makes it obsolete.

But like with business models, all technologies have half-lives, so it may be time to demonstrate the new technology.

The timing to do new work or make a change is never perfect. But if the timing is wrong, wait. But don’t wait too long.

If the timing isn’t right, adjust the approach to soften the conflict, e.g., pair a younger leader with a seasoned leader and move them both.

And if the timing is wrong but you think the new work cannot wait, start small.

And if the timing is horrifically wrong, start smaller.

It’s good to have experience, until the fundamentals change.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

The system works well when we correctly match the historical context with today’s context and the system’s fundamentals remain unchanged. There are two potential failure modes here. The first is when we mistakenly map the context of today’s situation with a memory-context pair that does not apply. With this, we misapply our experience-based knowledge in a context that demands different knowledge and different decisions. The second (and more dangerous) failure mode is when we correctly identify the match between past and current contexts but the rules that underpin the context have changed. Here, we feel good that we know how things will turn out, and, at the same time, we’re oblivious to the reality that our experience-based knowledge is out of date.

“If a cat sits on a hot stove, that cat won’t sit on a hot stove again. That cat won’t sit on a cold stove either. That cat just don’t like stoves.” Mark Twain

If you tried something ten years ago and it failed, it’s possible that the underpinning technology has changed and it’s time to give it another try.

If you’ve been successful doing the same thing over the last ten years, it’s possible that the underpinning business model has changed and it’s time to give a different one a try.

“Hissing cat” by Consumerist Dot Com is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Problems, Learning, Business Models, and People

If you know the right answer, you’re working on an old problem or you’re misapplying your experience.

If you know the right answer, you’re working on an old problem or you’re misapplying your experience.

If you are 100% sure how things will turn out, let someone else do it.

If there’s no uncertainty, there can be no learning.

If there’s no learning, your upstart competitors are gaining on you.

If you don’t know what to do, you’ve started the learning cycle.

If you add energy to your business model and it delivers less output, it’s time for a new business model.

If you wait until you’re sure you need a new business model, you waited too long.

Successful business models outlast their usefulness because they’ve been so profitable.

When there’s a project with a 95% chance to increase sales by 3%, there’s no place for a project with a 50% chance to increase sales by 100%.

When progress has slowed, maybe the informal networks have decided slower is faster.

If there’s something in the way, but you cannot figure out what it is, it might be you.

“A bouquet of wilting adapters” by rexhammock is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Your core business is your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

Your core business, the long-standing business that has made you what you are, is both your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

Your core business, the long-standing business that has made you what you are, is both your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

The Core generates the revenue, but it also starves fledgling businesses so they never make it off the ground.

There’s a certainty with the Core because it builds on success, but its success sets the certainty threshold too high for new businesses. And due to the relatively high level of uncertainty of the new business (as compared to the Core) the company can’t find the gumption to make the critical investments needed to reach orbit.

The Core has generated profits over the decades and those profits have been used to create the critical infrastructure that makes its success easier to achieve. The internal startup can’t use the Core’s infrastructure because the Core doesn’t share. And the Core has the power to block all others from taking advantage of the infrastructure it created.

The Core has grown revenue year-on-year and has used that revenue to build out specialized support teams that keep the flywheel moving. And because the Core paid for and shaped the teams, their support fits the Core like a glove. A new offering with a new value proposition and new business model cannot use the specialized support teams effectively because the new offering needs otherly-specialized support and because the Core doesn’t share.

The Core pays the bills, and new ventures create bills that the Core doesn’t like to pay.

If the internal startup has to compete with the Core for funding, the internal startup will fail.

If the new venture has to generate profits similar to the Core, the venture will be a misadventure.

If the new offering has to compete with the Core for sales and marketing support, don’t bother.

If the fledgling business’s metrics are assessed like the Core’s metrics, it won’t fly, it will flounder.

If you try to run a new business from within the Core, the Core will eat it.

To work effectively with the Core, borrow its resources, forget how it does the work, and run away.

To protect your new ventures from the Core, physically separate them from the Core.

To protect your new businesses from the Core, create a separate budget that the Core cannot reach.

To protect your internal startup from the Core, make sure it needs nothing from the Core.

To accelerate the growth of the fledgling business, make it safe to violate the Core’s first principles.

To bolster the capability of your new business, move resources from the Core to the new business.

To de-risk the internal startup, move functional support resources from the Core to the startup.

To fund your new ventures, tax the Core. It’s the only way.

“Core Memory” by JD Hancock is licensed under CC BY 2.0

A Recipe to Grow Revenue Now

If you want to grow the top line right now, create a hard constraint – the product cannot change – and force the team to look for growth outside the product. Since all the easy changes to the product have been made, without a breakthrough the small improvements bring diminishing returns. There’s nothing left here. Make them look elsewhere.

If you want to grow the top line right now, create a hard constraint – the product cannot change – and force the team to look for growth outside the product. Since all the easy changes to the product have been made, without a breakthrough the small improvements bring diminishing returns. There’s nothing left here. Make them look elsewhere.

If you want to grow the top line without changing the product, make it easier for customers to buy the products you already have.

If you want to make it easier for customers to buy what you have, eliminate all things that make buying difficult. Though this sounds obvious and trivial, it’s neither. It’s exceptionally difficult to see the waste in your processes from the customers’ perspective. The blackbelts know how to eliminate waste from the company’s perspective, but they’ve not been taught to see waste from the customers’ perspective. Don’t believe me? Look at the last three improvements you made to the customers’ buying process and ask yourself who benefitted from those changes. Odds are, the changes you made reduced the number of people you need to process the transactions by pushing the work back into the customers’ laps. This is the opposite of making it easier for your customers to buy.

Have you ever run a project to make it easier for customers to buy from you?

If you want to make it easier for customers to buy the products you have, pretend you are a customer and map their buying process. What you’ll likely learn is that it’s not easy to buy from you.

How can you make it easier for the customer to choose the right product to buy? Please don’t confuse this with eliminating the knowledgeable people who talk on the phone with customers. And, fight the urge to display all your products all at once. Minimize their choices, don’t maximize them.

How can you make it easier for customers to buy what they bought last time? A hint: when an existing customer hits your website, the first thing they should see is what they bought last time. Or, maybe, a big button that says – click here to buy [whatever they bought last time]. This, of course, assumes you can recognize them and can quickly match them to their buying history.

How can you make it easier for customers to pay for your product? Here’s a rule to live by: if they don’t pay, you don’t sell. And here’s another: you get no partial credit when a customer almost pays.

As you make these improvements, customers will buy more. You can use the incremental profits to fund the breakthrough work to obsolete your best products.

“Shopping Cart” by edenpictures is licensed under CC BY 2.0

When your company looks in the mirror, what does it see?

There are many types of companies, and it can be difficult to categorize them. And even within the company itself, there is disagreement about the company’s character. And one of the main sources of disagreement is born from our desire to classify our company as the type we want it to be rather than as the type that it is.

There are many types of companies, and it can be difficult to categorize them. And even within the company itself, there is disagreement about the company’s character. And one of the main sources of disagreement is born from our desire to classify our company as the type we want it to be rather than as the type that it is.

Here’s a process that may bring consensus to your company.

For all the people on the payroll, assign a job type and tally them up for the various types. If most of your people work in finance, you work for a finance company. If most work in manufacturing, you work for a manufacturing company. The same goes for sales, engineering, customer service, consulting. Write your answer here __________.

For all the company’s profits, assign a type and roll up the totals. If most of the profit is generated through the sale of services, you work for a service company. If most of the profit is generated by the sale of software, you work for a software company. If hardware generates profits, you work for a hardware company. If licensing of technology generates profits, you work at a technology company. Which one fits your company best? Write your answer here _________.

For all the people on the payroll, decide if they work to extend and defend the core offerings (the things that you sell today) or create new offerings in new markets that are sold to new customers. If most of the people work on the core offerings, you work for a low-growth company. If most of the people work to create new offerings (non-core), you work for a high-growth company. Which fits you best – extend and defined the core / low-growth or new offerings / high growth? Write your answer here __________ / ___________.

Now, circle your answers below.

We are a (finance, manufacturing, sales, engineering, customer service, consulting) company that generates most of its profits through the sale of (services, hardware, software, technology). And because most of our people work to (extend and defend the core, create new offerings), we are a (low, high) growth company.

To learn what type of company you work for, read the sentences out loud.

“Grace – Mirror” by phil41dean is licensed under CC BY 2.0

What should we do next?

Anonymous: What do you think we should do next?

Anonymous: What do you think we should do next?

Me: It depends. How did you get here?

Anonymous: Well, we’ve had great success improving on what we did last time.

Me: Well, then you’ll likely do that again.

Anonymous: Do you think we’ll be successful this time?

Me: It depends. If the performance/goodness has been flat over your last offerings, then no. When performance has been constant over the last several offerings it means your technology is mature and it’s time for a new one. Has performance been flat over the years?

Anon: Yes, but we’ve been successful with our tried-and-true recipe and the idea of creating a new technology is risky.

Me: All things have a half-life, including successful business models and long-in-the-tooth technologies, and your success has blinded you to the fact that yours are on life support. Developing a new technology isn’t risky. What’s risk is grasping tightly to a business model that’s out of gas.

Anon: That’s harsh.

Me: I prefer “truthful.”

Anon: So, we should start from scratch and create something altogether new?

Me: Heavens no. That would be a disaster. Figure out which elements are blocking new functionality and reinvent those. Hint: look for the system elements that haven’t changed in a dog’s age and that are shared by all your competitors.

Anon: So, I only have to reinvent several elements?

Me: Yes, but probably fewer than several. Probably just one.

Anon: What if we don’t do that?

Me: Over the next five years, you’ll be successful. And then in year six, the wheels will fall off.

Anon: Are you sure?

Me: No, they could fall off sooner.

Anon: How do you know it will go down like that?

Me: I’ve studied systems and technologies for more than three decades and I’ve made a lot of mistakes. Have you heard of The Voice of Technology?

Anon: No.

Me: Well, take a bite of this – The Voice of Technology. Kevin Kelly has talked about this stuff at great length. Have you read him?

Anon: No.

Me: Here’s a beauty from Kevin – What Technology Wants. How about S-curves?

Anon: Nope.

Me: Here’s a little primer – Beyond Dead Reckoning. How about Technology Forecasting?

Anon: Hmm. I don’t think so.

Me: Here’s something from Victor Fey, my teacher. He worked with Altshuller, the creator of TRIZ – Guided Technology Evolution. I’ve used this method to predict several industry-changing technologies.

Anon: Yikes! There’s a lot here. I’m overwhelmed.

Me: That’s good! Overwhelmed is a sign you realize there’s a lot you don’t know. You could be ready to become a student of the game.

Anon: But where do I start?

Me: I’d start Wardley Maps for situation analysis and LEANSTACK to figure out if customers will pay for your new offering.

Anon: With those two I’m good to go?

Me: Hell no!

Anon: What do you mean?

Me: There’s a whole body of work to learn about. Then you’ve got to build the organization, create the right mindset, select the right projects, train on the right tools, and run the projects.

Anon: That sounds like a lot of work.

Me: Well, you can always do what you did last time. END.

“he went that way matey” by jim.gifford is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The Power of Prototypes

A prototype moves us from “That’s not possible.” to “Hey, watch this!”

A prototype moves us from “That’s not possible.” to “Hey, watch this!”

A prototype moves us from “We don’t do it that way.” to “Well, we do now.”

A prototype moves us from “That’s impossible.” to “As it turns out, it was only almost impossible.”

A prototype turns naysayers into enemies and profits.

A prototype moves us from an argument to a new product development project.

A prototype turns analysis-paralysis into progress.

A prototype turns a skeptical VP into a vicious advocate.

A prototype turns a pet project into top-line growth.

A prototype turns disbelievers into originators of the idea.

A prototype can turn a Digital Strategy into customer value.

A prototype can turn an uncomfortable Board of Directors meeting into a pizza party.

A prototype can save a CEO’s ass.

A prototype can be too early, but mostly they’re too late.

If the wheels fall off your first prototype, you’re doing it right.

If your prototype doesn’t dismantle the Status-Quo, you built the wrong prototype.

A good prototype violates your business model.

A prototype doesn’t care if you see it for what it is because it knows everyone else will.

A prototype turns “I don’t believe you.” into “You don’t have to.”

When you’re told “Don’t make that prototype.” you’re onto something.

A prototype eats not-invented-here for breakfast.

A prototype can overpower the staunchest critic, even the VP flavor.

A prototype moves us from “You don’t know what you’re talking about.” to “Oh, yes I do.”

If the wheels fall off your second prototype, keep going.

A prototype is objective evidence you’re trying to make a difference.

You can argue with a prototype, but you’ll lose.

If there’s a mismatch between the theory and the prototype, believe the prototype.

A prototype doesn’t have to do everything, but it must do one important thing for the first time.

A prototype must be real, but it doesn’t have to be really real.

If your prototype obsoletes your best product, congratulations.

A prototype turns political posturing into reluctant compliance and profits.

A prototype turns “What the hell are you talking about?” into “This.”

A good prototype bestows privilege on the prototyper.

A prototype can beat a CEO in an arm-wrestling match.

A prototype doesn’t care if you like it. It only cares about creating customer value.

If there’s an argument between a well-stated theory and a well-functioning prototype, it’s pretty clear which camp will refine their theory to line up with what they just saw with their own eyes.

A prototype knows it has every right to tell the critics to “Kiss my ass.” but it knows it doesn’t have to.

You can argue with a prototype, but shouldn’t.

A prototype changes thinking without asking for consent.

Image credit — Pedro Ribeiro Simões

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski