Posts Tagged ‘Success’

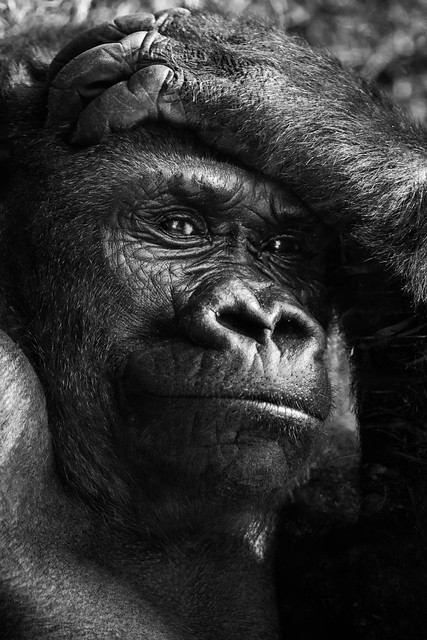

520 Wednesdays in a Row

This is a special post for me. It’s a huge milestone. With this post, I have written a new blog post every Wednesday evening for the last ten years. That’s 520 Wednesdays in a row. I haven’t missed a single one and none have been repeats. As I write this, the significance is starting to sink in.

This is a special post for me. It’s a huge milestone. With this post, I have written a new blog post every Wednesday evening for the last ten years. That’s 520 Wednesdays in a row. I haven’t missed a single one and none have been repeats. As I write this, the significance is starting to sink in.

Most of the posts I’ve written at the kitchen table with my earbuds set firmly in my ears and my family going about its business around me. But I’ve written them in the car; I’ve written them in a hospital waiting room; I’ve written them in a diner over lunch while on a three-week motorcycle trip, and I’ve written them at a state park while on vacation. No matter what, I’ve published a post on Wednesday night.

I write to challenge myself. I write to teach myself. I write to provide my own mentorship. I have no one to proof my writing and there are always mistakes of grammar, spelling and word choice. But that doesn’t stop me. No one limits the topics I cover, nor does anyone help me choose a topic. It’s just me and my laptop battling it out. It doesn’t have to be that way, but that’s the way it has been for the last ten years.

I used to read, respond and obsess over comments written by readers, but I started to limit my writing based on them so now my posts are closed to comments. I write more freely now, but I miss the connection that came from the comments.

I used to obsessively track the number of subscribers and Google analytics data. Now I don’t know how many subscribers I have, nor do I know who has visited my website over the last couple of years. Now I just write. But maybe I should check.

When you can write about anything you want, the topics you choose make a fingerprint, or maybe a soul-print. I don’t know what my choices say about me, but that’s the old me.

What’s the grand plan? There isn’t one. What’s next? It’s uncertain.

Thanks for reading.

Mike

image credit — Joey Gannon

Disruption – the work that makes the best things obsolete.

I think the word “disruption” doesn’t help us do the right work. Instead, I use “innovation.” But that word has also lost much of its usefulness. There are different flavors of innovation and the flavor that maps to disruption is the flavor that makes things obsolete. This flavor of new work doesn’t improve things, it displaces them. So, when you see “innovation” in my posts, think “work that makes the best things obsolete.”

Doing work that makes the best things obsolete requires new behavior. Here’s a post that gives some tips to help make it easy for new behaviors to come to be. Within the blog post, there is a link to a short podcast that’s worth a listen. One Good Way to Change Behavior

And here’s a follow-on post about what gets in the way of new behavior. What’s in the way?

It’s difficult to define “disruption.” Instead of explaining what disruption is or isn’t, I like to use “no-to-yes.” Don’t improve the system by 3%, instead use no-to-yes to make the improved system do something the existing system cannot. Battle Success With No-to-Yes

Instead of “disruption” I like “compete with no one.” To compete with no one, you’ve got to make your services so fundamentally good that your competition doesn’t stand a chance. Compete With No One

Disruption, as a word, is not actionable. But here’s what is actionable: Choose to solve new problems. Choose to solve problems that will make today’s processes and outcomes worthless. Before you solve a problem ask yourself “Will the solution displace what we have today?” Innovation In Three Words

Here’s a nice operational definition of how to do disruption – Obsolete your best work.

And if you’re not yet out of gas, here are some posts that describe what gets in the way of new behavior and how to create the right causes and conditions for new behaviors to emerge.

Creating the Causes and Conditions for New Behavior to Grow

The only thing predictable about innovation is its unpredictability.

For innovation to flow, drive out fear.

Image credit — Thomas Wensing

Seeing Things as They Can’t Be

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

Seeing things as they are. The same logic applies when it’s time to improve an existing product or service. The first thing to do is to see the system as it is. But seeing things as they are is difficult. We have a tendency to see things as we want them or to see them in ways that make us look good (or smart). Or, we see them in a way that justifies the improvements we already know we want to make.

To battle our biases and see things as they are, we use tools such as block diagrams to define the system as it is. The most important element of the block diagram is clarity. The first revision will be incorrect, but it must be clear and explicit. It must describe things in a way that creates a singular understanding of the system. The best block diagrams can be interpreted only one way. More strongly, if there’s ambiguity or lack of clarity, the thing has not yet risen to the level of a block diagram.

The block diagram evolves as the team converges on a single understanding of things as they are. And with a diagram of things as they are, a solution is readily defined and validated. If when tested the proposed solution makes the problem go away, it’s inferred that the team sees things as they are and the solution takes advantage of that understanding to make the problem go away.

Seeing things as they may be. Even whey the solution fixes the problem, the team really doesn’t know if they see things as they are. Really, all they know is they see things as they may be. Sure, the solution makes the problem go away, but it’s impossible to really know if the solution captures the physics of failure. When the system is large and has a lot of moving parts, the team cannot see things as they are, rather, they can only see the system as it may be. This is especially true if the system involves people, as people behave differently based on how they feel and what happened to them yesterday.

There’s inherent uncertainty when working with larger systems and systems that involve people. It’s not insurmountable, but you’ve got to acknowledge that your understanding of the system is less than perfect. If your company is used to solving small problems within small systems, there will be little tolerance for the inherent uncertainty and associated unpredictability (in time) of a solution. To help your company make the transition, replace the language of “seeing things as they are” with “seeing things as they may be.” The same diagnostic process applies, but since the understanding of the system is incomplete or wrong, the proposed solutions cannot not be pre-judged as “this will work” and “that won’t work.” You’ve got to be open to all potential solutions that don’t contradict the system as it may be. And you’ve got to be tolerant of the inherent unpredictability of the effort as a whole.

Seeing things as they could be. To create something that doesn’t yet exist, something does things like never before, something altogether new, you’ve got to stand on top of your understanding of the system and jump off. Whether you see things as they are or as they may be, the new system will be different. It’s not about diagnosing the existing system; it’s about imagining the system as it could be. And there’s a paradox here. The better you understand the existing system, the more difficulty you’ll have imagining the new one. And, the more success the company has had with the system as it is, the more resistance you’ll feel when you try to make the system something it could be.

Seeing things as they could be takes courage – courage to obsolete your best work and courage to divest from success. The first one must be overcome first. Your body creates stress around the notion of making yourself look bad. If you can create something altogether better, why didn’t you do it last time? There’s a hit to the ego around making your best work look like it’s not all that good. But once you get over all that, you’ve earned the right to go to battle with your organization who is afraid to move away from the recipe responsible for all the profits generated over the last decade.

But don’t look at those fears as bad. Rather, look at them as indicators you’re working on something that could make a real difference. Your ego recognizes you’re working on something better and it sends fear into your veins. The organization recognizes you’re working on something that threatens the status quo and it does what it can to make you stop. You’re onto something. Keep going.

Seeing things as they can’t be. This is rarified air. In this domain you must violate first principles. In this domain you’ve got to run experiments that everyone thinks are unreasonable, if not ill-informed. You must do the opposite. If your product is fast, your prototype must be the slowest. If the existing one is the heaviest, you must make the lightest. If your reputation is based on the highest functioning products, the new offering must do far less. If your offering requires trained operators, the new one must prevent operator involvement.

If your most seasoned Principal Engineer thinks it’s a good idea, you’re doing it wrong. You’ve got to propose an idea that makes the most experienced people throw something at you. You’ve got to suggest something so crazy they start foaming at the mouth. Your concepts must rip out their fillings. Where “seeing things as they could be” creates some organizational stress, “seeing things as they can’t be” creates earthquakes. If you’re not prepared to be fired, this is not the domain for you.

All four of these domains are valuable and have merit. And we need them all. If there’s one message it’s be clear which domain you’re working in. And if there’s a second message it’s explain to company leadership which domain you’re working in and set expectations on the level of uncertainty and unpredictability of that domain.

Image credit – David Blackwell.

You don’t need more ideas.

Innovation isn’t achieved by creating more ideas. Innovation is realized when ideas are transformed into commercialized products and services. Innovation is realized when ideas are transformed into new business models that deliver novel usefulness to customers and deliver increased revenues to the company.

Innovation isn’t achieved by creating more ideas. Innovation is realized when ideas are transformed into commercialized products and services. Innovation is realized when ideas are transformed into new business models that deliver novel usefulness to customers and deliver increased revenues to the company.

In a way, creating ideas that languish in their own shadow is worse than not creating any ideas at all. If you don’t have any ideas, at least you didn’t spend the resources to create them and you don’t create the illusion that you’re actually making progress. In that way, it’s better to avoid creating new ideas if you’re not going to do anything with them. At least your leadership team will not be able to rationalize that everything will be okay because you have an active idea generation engine.

Before you schedule your next innovation session, don’t. Reason 1 – it’s not an innovation session, it’s an ideation session. Reason 2 – you don’t have resources to do anything with the best ideas so you’ll spend the resources and nothing will come of it. To improve the return on investment, don’t make the investment because there’ll be no return.

Truth is, you already have amazing ideas to grow your company. Problem is, no one is listening to the people with the ideas. And the bigger problem – because no one listened over the last ten years, the people with the ideas have left the company or stopped trying to convince you they have good ideas. Either way, you’re in trouble and creating more ideas won’t help you. Your culture is such that new ideas fall on deaf ears and funding to advance new concepts loses to continuous improvement.

If you do want to hold an ideation event to create new ideas that will reinvent your company, there are ways to do it effectively. First, define the customer of the ideation event. This is the person who is on the hook to commercialize things that will grow the business. This is the person who will have a career problem if ideas aren’t implemented. This is the person who can allocate the resources to turn the ideas into commercialized products, services. If this person isn’t an active advocate for the ideation event, don’t hold it. If this person will not show up to the report out of the ideation event, don’t hold it. If this person does not commit to advancing the best ideas, don’t hold the event.

Though innovation and ideas start with “i”, they’re not the same. Ideas are inexpensive to create but deliver no value. Innovation is expensive and delivers extreme value to customers and the company. If you’re not willing to convert the ideas into something that delivers values to customers, save the money and do continuous improvement. Your best people will leave, but at least you won’t waste money on creating ideas that will die on the vine.

If the resources aren’t lined up to run with the ideas, don’t generate the them. If you haven’t allocated the funding for the follow-on work, don’t create new ideas. If the person who is charged with growing the business isn’t asking for new ideas, don’t hold the ideation event.

You already have too many ideas. But what you lack is too few active projects to convert the best ideas into products and services that generate value for your customers and growth for your company.

Stop creating new ideas and start delivering novel usefulness to your customers.

Image credit – Marco Nürnberger

You’re probably not doing transformational work.

Continuous improvement is not transformation. With continuous improvement, products, processes and services are improved three percent year-on-year. With transformation, products are a mechanism to generate data, processes are eliminated altogether and services move from fixing what’s broken to proactive updates that deliver the surprising customer value.

A strategic initiative is not transformation. A strategic initiative improves a function or process that is – a move to consultative selling or a better new product development process. Transformation dismantles. The selling process is displaced by automatic with month-to-month renewals. And while product development is still a thing, it’s relegated to a process that creates the platform for the real money-maker – the novel customer value made possible by the data generated by the product.

Cultural change is not transformation. Cultural change uses the gaps in survey data to tweak a successful formula and adjust messaging. Transformation creates new organizations that violate existing company culture.

If there the corporate structure is unchanged, there can be no transformation.

If the power brokers are unchanged, there can be no transformation.

If the company culture isn’t violated, there can be no transformation.

If it’s not digital, there can be no transformation.

In short, if the same rules apply, there can be no transformation.

Transformation doesn’t generate discomfort, it generates disarray.

Transformation doesn’t tweak the successful, it creates the unrecognizable.

Transformation doesn’t change the what, it creates a new how.

Transformation doesn’t make better caterpillars, it creates butterflies.

Image credit – Chris Sorge

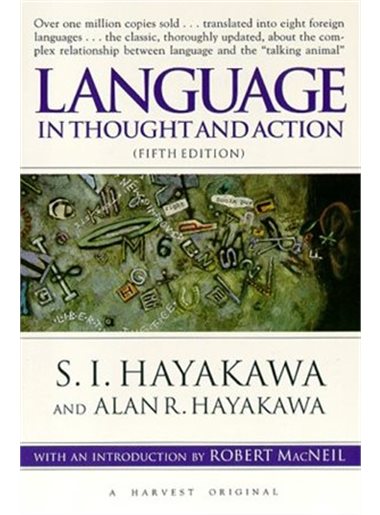

Why not choose the right words?

We all want to make progress. We all want to to do the right thing. And we all have the best intentions. But often we don’t pay enough attention to the words we use.

We all want to make progress. We all want to to do the right thing. And we all have the best intentions. But often we don’t pay enough attention to the words we use.

There are pure words that convey a message in a kind soothing way and there are snarl words that convey a message in a sharp, biting way. It’s relatively easy, if you’re paying attention, to recognize the snarl and purr. But it’s much more difficult to take skillful action when you hear them used unskillfully.

A purr word is skillful when it conveys honest appreciation, and it’s unskillful when it manipulates under the banner of false praise. But how do you tell the difference? That’s where the listening comes in. And that’s where effective probing can help.

If you sense unskillful use, ask a question of the user to get at the intent behind the language. Why do you think the idea is so good? What about the concept do you find so interesting? Why do you like it so much? Then, use your judgment to decide if the use was unskillful or not. If unskillful, assign less value to the purr language and the one purring it.

But it’s different with snark words. I don’t know of a situation where the use of snarl words is skillful. Blatant use of snarl words is easy to see and interpret. And it looks like plain, old-fashioned anger. And the response is straightforward. Call the snarler on their snarl and let them know it’s not okay. That usually puts an end to future snarling.

The most dangerous use of snarl words is passive-aggressive snarling. Here, the snarler wants all the manipulative benefit without being recognized as a manipulator. The pros snarl lightly to start to see if they get away with it. And if they do, they snarl harder and more often. And they won’t stop until they’re called on their behavior. And when they are called on their behavior, they’ll deny the snarling altogether.

Passive-aggressive snarling can block new thinking, prevent consensus and stall hard-won momentum. It’s nothing short of divisive. And it’s difficult to see and requires courage to confront and eviscerate.

If you see something, say something. And it’s the same with passive-aggressive snarling. If you think it is happening, ask questions to get at the underlying intent of the words. If it turns out that it’s simply a poor choice of words, suggest better ones and move on. But if the intent is manipulation, it must be stopped in its tracks. It must be called by name, its negative implications must be be linked to the behavior and new behavioral norms must be set.

Words are the tools we use to make progress. The wrong words block progress and the right ones accelerate it.

Why not choose the right words?

How To Innovate Within a Successful Company

If you’re trying to innovate within a successful company, I have one word for you: Don’t.

If you’re trying to innovate within a successful company, I have one word for you: Don’t.

You can’t compete with the successful business teams that pay the bills because paying the bills is too important. No one in their right mind should get in the way of paying them. And if you do put yourself in the way of the freight train that pays the bills you’ll get run over. If you want to live to fight another day, don’t do it.

If an established business has been growing three percent year-on-year, expect them to grow three percent next year. Sure, you can lather them in investment, but expect three and a half percent. And if they promise six percent, don’t believe them. In fairness, they truly expect they can grow six percent, but only because they’re drinking their own Cool-Aid.

Rule 1: If they’re drinking their own Cool-Aid, don’t believe them.

Without a cataclysmic problem that threatens the very existence of a successful company, it’s almost impossible to innovate within its four walls. If there’s no impending cataclysm, you have two choices: leave the four walls or don’t innovate.

It’s great to work at successful company because it has a recipe that worked. And it sucks to work at a successful company because everyone thinks that tired old recipe will work for the next ten years. Whether it will work for the next ten or it won’t, it’s still a miserable place to work if you want to try something new. Yes, I said miserable.

What’s the one thing a successful company needs? A group of smart people who are actively dissatisfied with the status quo. What’s the one thing a successful company does not tolerate? A group of smart people who are actively dissatisfied with the status quo.

Some experts recommend leveraging (borrowing) resources from the established businesses and using them to innovate. If the established business catches wind that their borrowed resources will be used to displace the status quo, the resources will mysteriously disappear before the innovation project can start. Don’t try to borrow resources from established businesses and don’t believe the experts.

Instead of competing with established businesses for resources, resources for innovation should be allocated separately. Decide how much to spend on innovation and allocate the resources accordingly. And if the established businesses cry foul, let them.

Instead of borrowing resources from established businesses to innovate, increase funding to the innovation units and let them buy resources from outside companies. Let them pay companies to verify the Distinctive Value Proposition (DVP); let them pay outside companies to design the new product; let them pay outside companies to manufacture the new product; and let them pay outside companies to sell it. Sure, it will cost money, but with that money you will have resources that put their all into the design, manufacture and sale of the innovative new offering. All-in-all, it’s well worth the money.

Don’t fall into the trap of sharing resources, especially if the sharing is between established businesses and the innovative teams that are charged with displacing them. And don’t fall into the efficiency trap. Established businesses need efficiency, but innovative teams need effectiveness.

It’s not impossible to innovate within a successful company, but it is difficult. To make it easier, error on the side of doing innovation outside the four walls of success. It may be more expensive, but it will be far more effective. And it will be faster. Resources borrowed from other teams work the way they worked last time. And if they are borrowed from a successful team, they will work like a successful team. They will work with loss aversion. Instead of working to bring something to life they will work to prevent loss of what worked last time. And when doing work that’s new, that’s the wrong way to work.

The best way I know to do innovation within a successful company is to do it outside the successful company.

Image credit – David Doe

Defy success and choose innovation.

Innovation is difficult because it requires novelty. And novelty is difficult because it’s different than last time. And different than last time is difficult because you’ve got to put yourself out there. And putting yourself out there is difficult because no one wants to be judged negatively.

Innovation is difficult because it requires novelty. And novelty is difficult because it’s different than last time. And different than last time is difficult because you’ve got to put yourself out there. And putting yourself out there is difficult because no one wants to be judged negatively.

Success, no matter how small, reinforces what was done last time. There’s safety in doing it again. The return may be small, but the wheels won’t fall off. You may run yourself into the ground over time, but you won’t fail catastrophically. You may not reach your growth targets, but you won’t get fired for slowly destroying the brand. In short, you won’t fail this year, but you will create the causes and conditions for a race to the bottom.

Diminishing returns are real. As a system improves it becomes more difficult to improve. A ten percent improvement is more difficult every year and at some point, improvement becomes impossible. In that way, success doesn’t breed success, it breeds more effort for less return. And as that improvement per unit effort decreases, it becomes ever more important (and ever more difficult) to do something different (to innovate).

Paradoxically, success makes it more difficult to innovate.

Success brings profits that could fund innovation. But, instead, success brings the expectation of predictable growth. Last year we were successful and grew 10%. We know the recipe, so this year let’s grow 12%. We can do what we did last year, but do it more efficiently. A sound bit of logic, except it assumes the rules haven’t changed and that competitors haven’t improved. But rules and competitors always change, and, at some point the the same old recipe for success runs out of gas.

It’s time to do something new (to innovate) when the same old effort brings reduced results. That change in output per unit effort means the recipe is tiring and it’s time for a new one. But with a new approach comes unpredictability, and for those who demand predictability, a new approach is scary. Sure, the yearly trend of reduced return on investment should scare them more, but it doesn’t. The devil you know is less scary than the one you don’t. But, it shouldn’t be.

Calculate your revenue dollars per sales associate and plot it over time. If the metric is flat over the last three years, it was time to innovate three years ago. If it’s decreasing over the last three years, it was time to innovate six years ago.

If you wait to innovate until revenue per sales person is flat, you waited too long.

No one likes to be judged negatively, more than that, no one likes their company to collapse and lose their job. So, choose to do something new (to innovate) and choose the possibility of being judged. That’s much better than choosing to go out of business.

Image credit – Michel Rathwell

Important Questions for Innovation

Here are some important questions for innovation.

Here are some important questions for innovation.

What’s the Distinctive Value Proposition? The new offering must help the customer make progress. How does the customer benefit? How is their life made easier? How does this compare to the existing offerings? Summarize the difference on one page. If the innovation doesn’t help the customer make progress, it’s not an innovation.

Is it too big or too small? If the project could deliver sales growth that would dwarf the existing sales numbers for the company, the endeavor is likely too big. The company mindset and philosophy would have to be destroyed. Are you sure you’re up to the challenge? If the project could deliver only a small increase in sales, it’s likely not worth the time and expense. Think return on investment. There’s no right answer, but it’s important to ask the question and set the limits for too big and too small. If it could grow to 10% of today’s sales numbers, that’s probably about right.

Why us? There’s got to be a reason why you’re the right company to do this new work. List the company’s strengths that make the work possible. If you have several strengths that give you an advantage, that’s great. And if one of your weaknesses gives you an advantage, that works too. Step on the accelerator. If none of your strengths give you an advantage, choose another project.

How do we increase our learning rate? First thing, define Learning Objectives (LOs). And once defined, create a plan to achieve them quickly. Here’s a hint. Define what it takes to satisfy the LOs. Here’s another hind. Don’t build a physical prototype. Instead, create a website that describes the potential offering and its value proposition and ask people if they want to buy it. Collect the data and refine the offering based on your learning. Or, create a one-page sales tool and show it to ten potential customers. Define your learning and use the learning to decide what to do next.

Then what? If the first phase of the work is successful, there must be a then what. There must be an approved plan (funding, resources) for the second phase before the first phase starts. And the same thing goes for the follow-on phases. The easiest way to improve innovation effectiveness is avoid starting phase one of projects when their phase two is unfunded. The fastest innovation project is the wrong one that never starts.

How do we start? Define how much money you want to spend. Formalize your business objectives. Choose projects that could meet your business objectives. Free up your best people. Learn as quickly as you can.

Image credit — Alexander Henning Drachmann

Three Rules for Better Decisions

The primary responsibility of management is to allocate resources in the way that best achieves business objectives. If there are three or four options to allocate resources, which is the best choice? What is the time horizon for the decision? Is it best to hire more people? Why not partner with a contract resource company? Build a new facility or add to the existing one? No right answers, but all require a decision.

The primary responsibility of management is to allocate resources in the way that best achieves business objectives. If there are three or four options to allocate resources, which is the best choice? What is the time horizon for the decision? Is it best to hire more people? Why not partner with a contract resource company? Build a new facility or add to the existing one? No right answers, but all require a decision.

Rule 1 – Make decisions overtly. All too often, decisions happen slowly over time without knowledge the decision was actually made. A year down the road, we wake up from our daze and realize we’re all aligned with a decision we didn’t know we made. That’s bad for business. Make them overtly and document them.

Rule 2 – Define the decision criteria before it’s time to decide. We all have biases and left to our own, we’ll make the decision that fits with our biases. For example, if we think the project is a good idea, we’ll interpret the project’s achievements through our biased lenses and fund the next phase. To battle this, define the decision criteria months before the funding decision will be made. Think if-then. If the project demonstrates A, then we’ll allocate $50,000 for the next phase; if the project demonstrates A, B and C, then we’ll allocate $100,000; if the project fails to demonstrate A, B or C, then we’ll scrap the project and start a new one. If the decision criteria aren’t predefined, you’ll define them on-the-spot to justify the decision you already wanted to make.

Rule 3 – Define who will decide before it’s time to decide. Will the decision be made by anonymous vote or by a show of hands? Is a simple majority sufficient, or does it require a two-thirds majority? Does it require a consensus? If so, does it have to be unanimous or can there be some disagreement? If there can be disagreement, how many people can disagree? Does the loudest voice decide? Or does the most senior person declare their position and everyone else falls in line like sheep?

Think back to the last time your company made a big decision. Were the decision criteria defined beforehand? Can you go back to the meeting minutes and find how the project performed against the decision criteria? Were the if-then rules defined upfront? If so, did you follow them? And now that you remember how it went last time, do you think you would have made a better decision if the decision criteria and if-thens were in place before the decision? Now, decide how it will go next time.

And for that last big decision, is there a record of how the decision was made? If there was a vote, who voted up and who voted down? If a consensus was reached, who overtly said they agreed to the decision and who dissented? Or did the most senior person declare a consensus when in fact it was a consensus of one? If you can find a record of the decision, what does the record show? And if you can’t find the record, how do you feel about that? Now that you reflected on last time, decide how it will go next time.

It’s scary to think about how we make decisions. But it’s scarier to decide we will make them the same way going forward. It’s time to decide we will put more rigor into our decision making.

Image credit – Michael J & Lesley

The Four Ways to Run Projects

There are four ways to run projects.

There are four ways to run projects.

One – 80% Right, 100% Done, 100% On Time, 100% On Budget

- Fix time

- Fix resources

- Flex scope and certainty

Set a tight timeline and use the people and budget you have. You’ll be done on time, but you must accept a reduced scope (fewer bells and whistles) and less certainty of how the product/service will perform and how well it will be received by customers. This is a good way to go when you’re starting a new adventure or investigating new space.

Two – 100% Right, 100% Done, 0% On Time, 0% On Budget

- Fix resources

- Fix scope and certainty

- Flex time

Use the team and budget you have and tightly define the scope (features) and define the level of certainty required by your customers. Because you can’t predict when the project will be done, you’ll be late and over budget, but your offering will be right and customers will like it. Use this method when your brand is known for predictability and stability. But, be weary of business implications of being late to market.

Three – 100% Right, 100% Done, 100% On Time, 0% On Budget

- Fix scope and certainty

- Fix time

- Flex resources

Tightly define the scope and level of certainty. Your customers will get what they expect and they’ll get it on time. However, this method will be costly. If you hire contract resources, they will be expensive. And if you use internal resources, you’ll have to stop one project to start this one. The benefits from the stopped project won’t be realized and will increase the effective cost to the company. And even though time is fixed, this approach will likely be late. It will take longer than planned to move resources from one project to another and will take longer than planned to hire contract resources and get them up and running. Use this method if you’ve already established good working relationships with contract resources. Avoid this method if you have difficulty stopping existing projects to start new ones.

Four – Not Right, Not Done, Not On Time, Not On Budget

- Fix time

- Fix resources

- Fix scope and certainty

Though almost every project plan is based on this approach, it never works. Sure, it would be great if it worked, but it doesn’t, it hasn’t and it won’t. There’s not enough time to do the right work, not enough money to get the work done on time and no one is willing to flex on scope and certainty. Everyone knows it won’t work and we do it anyway. The result – a stressful project that doesn’t deliver and no one feels good about.

Image credit – Cees Schipper

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski