Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

Effectiveness at the Expense of Efficiency

Efficiency is a simple measurement – output divided by resources needed to achieve it. How much did you get done and how many people did you need to do it? What was the return on the investment? How much money did you make relative to how much you had to invest? We have efficiency measurements for just about everything. We are an efficiency-based society.

Efficiency is a simple measurement – output divided by resources needed to achieve it. How much did you get done and how many people did you need to do it? What was the return on the investment? How much money did you make relative to how much you had to invest? We have efficiency measurements for just about everything. We are an efficiency-based society.

It’s easy to create a metric for efficiency. Figure out the output you can measure and divide it by the resources you think you used to achieve it. While a metric like this is easy to calculate, it likely won’t provide a good answer to what we think is the only question worth asking– how do we increase efficiency?

Problem 1. The resources you think are used to produce the output aren’t the only resources you used to generate the output. There are many resources that contributed to the output that you did not measure. And not only that, you don’t know how much those resources actually cost. You can try the tricky trick of fully burdened cost, where the labor rate is loaded with an overhead percentage. But that’s, well, nothing more than an artifact of a contrived accounting system. You can do some other stuff like calculate the opportunity cost of deploying those resources on other projects. I’m not sure what that will get you, but it won’t get you the actual cost of achieving the output you think you achieved.

Problem 2. We don’t measure what’s important or meaningful. We measure what’s easy to measure. And that’s a big problem because you end up beating yourself about the head and shoulders trying to improve something that is easy to measure but not all that meaningful. The biggest problem here is local optimization. You want something easy to measure so you cull out a small fraction of a larger process and increase the output of that small part of the process. The thing is, your customer doesn’t care about the efficiency of that small piece of that process. And, improving that small piece likely doesn’t do anything for the output of the total process. If more products aren’t leaving the factory, you didn’t do anything.

Problem 3. Productivity isn’t all that important. What’s important is effectiveness. If you are highly efficient at the wrong thing, you may be efficient, but you’re also ineffective. If you launch a product in a highly efficient way and no one buys it, your efficiency numbers may be off the charts, but your effectiveness numbers are in the toilet.

We have very few metrics on effectiveness. But here are some questions a good effectiveness metric should help you answer.

- Did we work on the right projects?

- Did we make good decisions?

- Did we put the right people on the projects?

- Did we do what we said we’d do?

- After the project, is the team excited to do a follow-on project?

- Did our customers benefit from our work?

- Do our partners want to work with us again?

- Did we set ourselves up to do our work better next time?

- Did we grow our young talent?

- Did we have fun?

- Do more people like to work at our company?

- Have we developed more trust-based relationships over the last year?

- Have we been more transparent with our workforce this year?

If I had a choice between efficiency and effectiveness, I’d choose effectiveness.

Image credit – Bruce Tuten

Want to succeed? Learn how to deliver customer value.

Whatever your initiative, start with customer value. Whatever your project, base it on customer value. And whatever your new technology, you guessed it, customer value should be front and center.

Whatever your initiative, start with customer value. Whatever your project, base it on customer value. And whatever your new technology, you guessed it, customer value should be front and center.

Whenever the discussion turns to customer value, expect confusion, disagreement, and, likely, anger. To help things move forward, here’s an operational definition I’ve found helpful:

When they buy it for more than your cost to make it, you have customer value.

And when there’s no way to pull out of the death spiral of disagreement, use this operational definition to avoid (or stop) bad projects:

When no one will buy it, you don’t have customer value and it’s a bad project.

As two words, customer and value don’t seem all that special. But, when you put them together, they become words to live by. But, also, when you do put them together, things get complicated. Here’s why.

To provide customer value, you’ve got to know (and name) the customer. When you asked “Who is the customer?” the wheels fall off. Here are some wrong answers to that tricky question. The Board of Directors is the customer. The shareholders are the customers. The distributor is the customer. The OEM that integrates your product is the customer. And the people that use the product are the customer. Here’s an operational definition that will set you free:

When someone buys it, they are the customer.

When the discussions get sticky, hold onto that definition. Others will try to bait you into thinking differently, but don’t bite. It will be difficult to stand your ground. And if you feel the group is headed in the wrong direction, try to set things right with this operational definition:

When you’ve found the person who opens their wallet, you’ve found the customer.

Now, let’s talk about value. Isn’t value subjective? Yes, it is. And the only opinion that matters is the customer’s. And here’s an operational definition to help you create customer value:

When you solve an important customer problem, they find it valuable.

And there you have it. Putting it all together, here’s the recipe for customer value:

- Understand who will buy it.

- Understand their work and identify their biggest problem.

- Solve their problem and embed it in your offering.

- Sell it for more than it costs you to make it.

Image credit — Caroline

Love Everyone and Tell the Truth

If you see someone doing something that’s not quite right, you have a choice – call them on their behavior or let it go.

If you see someone doing something that’s not quite right, you have a choice – call them on their behavior or let it go.

In general, I have found it’s more effective to ignore behavior you deem unskillful if you can. If no one will get hurt, say nothing. If it won’t start a trend, ignore it. And if it’s a one-time event, look the other way. If it won’t cause standardization on a worst practice, it never happened.

When you don’t give attention to other’s unskillful behavior, you don’t give it the energy it needs to happen again. Just as a plant dies when it’s not watered, unskillful behavior will wither on the vine if it’s ignored. Ignore it and it will die. But the real reason to ignore unskillful behavior is that it frees up time to amplify skillful behavior.

If you’re going to spend your energy doing anything, reinforce skillful behavior. When you see someone acting skillfully, call it out. In front of their peers, tell them what you liked and why you liked it. Tell them how their behavior will make a difference for the company. Say it in a way that others hear. Say it in a way that everyone knows this behavior is special. And if you want to guarantee that the behavior will happen again, send an email of praise to the boss of the person that did the behavior and copy them on the email. The power of sending an email of praise is undervalued by a factor of ten.

When someone sends your boss an email that praises you for your behavior, how do you feel?

When someone sends your boss an email that praises you for your behavior, will you do more of that behavior or less?

When someone sends your boss an email that praises you for your behavior, what do you think of the person that sent it?

When someone sends your boss an email that praises you for your behavior, will you do more of what the sender thinks important or less?

And now the hard part. When you see someone behaving unskillfully and that will damage your company’s brand, you must call them on their behavior. To have the most positive influence, give your feedback as soon as you see it. In a cause-and-effect way, the person learns that the unskillful behavior results in a private discussion on the negative impact of their behavior. There’s no question in their mind about why the private discussion happened and, because you suggested a more skillful approach, there’s clarity on how to behave next time. The first time you see the unskillful behavior, they deserve to be held accountable in private. They also deserve a clear explanation of the impacts of their behavior and a recipe to follow going forward.

And now the harder part. If, after the private explanation of the unskillful behavior that should stop and the skillful behavior should start, they repeat the unskillful behavior, you’ve got to escalate. Level 1 escalation is to hold a private session with the offender’s leader. This gives the direct leader a chance to intervene and reinforce how the behavior should change. This is a skillful escalation on your part.

And now the hardest part. If, after the private discussion with the direct leader, the unskillful behavior happens again, you’ve got to escalate. Remember, this unskillful behavior is so unskillful it will hurt the brand. It’s now time to transition from private accountability to public accountability. Yes, you’ve got to call out the unskillful behavior in front of everyone. This may seem harsh, but it’s not. They and their direct leader have earned every bit of the public truth-telling that will soon follow.

Now, before going public, it’s time to ask yourself two questions. Does this unskillful behavior rise to the level of neglect? And, does this unskillful behavior violate a first principle? Meaning, does the unskillful behavior undermine a fundamental, or foundational element, of how the work is done? Take your time with these questions, because the situation is about to get real. Really real. And really uncomfortable.

And if you answer yes to one of those two questions, you’ve earned the right to ask yourself a third. Have you reached bedrock? Meaning, your position grounded deeply in what you believe. Meaning, you’ve reached a threshold where things are non-negotiable. Meaning, no matter what the negative consequences to your career, you’re willing to stand tall and take the bullets. Because the bullets will fly.

If you’ve reached bedrock, call out the unskillful behavior publicly and vehemently. Show no weakness and give no ground. And when the push-back comes, double down. Stand on your bedrock, and tell the truth. Be effective, and tell the truth. As Ram Dass said, love everyone and tell the truth.

If you want to make a difference, amplify skillful behavior. Send emails of praise. And if that doesn’t work, send more emails of praise. Praise publicly and praise vehemently. Pour gasoline on the fire. And ignore unskillful behavior, when you can.

And when you can’t ignore the unskillful behavior, before going public make sure the behavior violates a first principle. And make sure you’re standing on bedrock. And once you pass those tests, love everyone and tell the truth.

Image credit — RamDass.org

Learn to Recognize Waiting

If you want to do a task, but you don’t have what you need, that’s waiting for a support resource. If you need a tool, but you don’t have it, you wait for a tool. If you need someone to do the task, but you don’t have anyone, you wait for people. If you need some information to make a decision, but you don’t have it, you wait for information.

If a tool is expensive, usually you have to wait for it. The thinking goes like this – the tool is expensive, so let’s share the cost over too many projects and too many teams. Sure, less work will get done, but when we run the numbers, the tool will look less expensive because it’s used by many people. If you see a long line of people (waiting) or a signup list (people waiting at their desks), what they are waiting for is usually an expensive tool or resource. In that way, to find the cause of waiting, stand at the front of the line and look around. What you see is the cause of the waiting.

If the tool isn’t expensive, buy another one and reduce the waiting. If the tool is expensive, calculate the cost of delay. Cost of delay is commonly used with product development projects. If the project is delayed by a month, the incremental revenue from the product launch is also delayed by a month. That incremental revenue is the cost of delaying the project by a month. When the cost of delay is larger than the cost of an expensive tool, it makes sense to buy another expensive tool. But, to purchase that expensive tool requires multiple levels of approvals. So, the waiting caused by the tool results in waiting for approval for the new tool. I guess there’s a cost of delay for the approval process, but let’s not go there.

Most companies have more projects than people, and that’s why projects wait. And when projects wait, projects are late. Adding people is like getting another expensive tool. They are spread over too many projects, and too little gets done. And like with expensive tools, getting more people doesn’t come easy. New hires can be justified (more waiting in the approval queue), but that takes time to find them, hire them, and train them. Hiring temporary people is a good option, though that can seem too expensive (higher hourly rate), it requires approval, and it takes time to train them. Moving people from one project to another is often the best way because it’s quick and the training requirement is less. But, when one project gains a person, another project loses one. And that’s often the rub.

When it’s time to make an important decision and the team has to wait for missing information, the project waits. And when projects wait, projects are late. It’s difficult to see the waiting caused by missing or uncommunicated information, but it can be done. The easiest to see when the information itself is a project deliverable. If a milestone review requires a formal presentation of the information, the review cannot be held without it. The delay of the milestone review (waiting) is objective evidence of missing information.

Information-based waiting is relatively easy to see when the missing information violates a precedent for decision making. For example, if the decision is always made with a defined set of data or information, and that information is missing, the precedent is violated and everyone knows the decision cannot be made. In this case, everyone’s clear why the decision cannot be made, everyone’s clear on what information is missing, and everyone’s clear on who dropped the ball.

It’s most difficult to recognize information-based waiting when the decision is new or different and requires judgment because there’s no requirement for the data and there’s no precedent to fall back on. If the information was formally requested and linked to the decision, it’s clear the information is missing and the decision will be delayed. But if it’s a new situation and there’s no agreement on what information is required for the decision, it’s almost impossible to discern if the information is missing. In this situation, it comes down to trust in the decision-maker. If you trust the decision-maker and they say there’s information missing, then there’s information missing. If you trust the decision-maker and they say there’s no information missing, they should make the decision. But if you don’t trust the decision-maker, then all bets are off.

In general, waiting is bad. And it’s helpful if you can recognize when projects are waiting. Waiting is especially bad went the delayed task is on the critical path because when the project is waiting on a task that’s on the critical path, there’s a day-for-day slip in the completion date. Hint: it’s important to know which tasks and decisions are on the critical path.

Image credit — Tomasz Baranowski

Stop, Start, Continue the Hard Way

The stop, start, continue method (SSC) is a simple, yet powerful, way to plan your day, week and year. And though it’s simple, it’s not simplistic. And though it looks straightforward, it’s onion-like in its layers.

The stop, start, continue method (SSC) is a simple, yet powerful, way to plan your day, week and year. And though it’s simple, it’s not simplistic. And though it looks straightforward, it’s onion-like in its layers.

Stop, start, continue (SSC) is interesting in that it’s forward-looking, present-looking, and rearward-looking at the same time. And its power comes from the requirement that the three time perspectives must be reconciled with each other. Stopping is easy, but what will start? Starting is easy, unless nothing is stopped. Continuing is easy, but it’s not the right thing if the rules have changed. And starting can’t start if everything continues.

Stop. With SSC, stopping is the most important part. That’s why it’s first in the sequence. When everyone’s plates are full and every meeting is an all-you-can-eat buffet, without stopping, all the new action items slathered on top simply slip off the plate and fall to the floor. And this is double trouble because while it’s clear new action items are assigned, there’s no admission that the carpet is soiled with all those recently added action items.

Here’s a rule: If you don’t stop, you can’t start.

And here’s another: Pros stop, and rookies start.

With continuous improvement, you should stop what didn’t work. But with innovation, you should stop what was successful. Let others fan the flames of success while you invent the new thing that will start a bigger blaze.

Start. With SSC, starting is the easy part, but it shouldn’t be. Resources are finite, but we conveniently ignore this reality so we can start starting. The trouble with starting is that no one wants to let go of continuing. Do everything you did last year and start three new initiatives. Continue with your current role, but start doing the new job so you can get the promotion in three years.

Here’s a rule: Starting must come at the expense of continuing.

And here’s another: Pros do stop, start, continue, and rookies do start, start, start.

Continue. With SSC, continue is underrated. If you’re always starting, it’s because you have nothing good to continue. And if you’ve got a lot of continuing to do, it’s because you’ve got a lot of good things going on. And continuing is efficient because you’re not doing something for the first time. And everyone knows how to do the work and it goes smoothly.

But there’s a dark side to continue – it’s called the status quo. The status quo is a powerful, one-trick pony that only knows how to continue. It hates stopping and blocks all starting. Continuing is the mortal enemy of innovation.

Here’s a rule: Continuing must stop, or starting can’t start.

And here’s another: Pros continue and stop before they start, and rookies start.

SSC is like juggling three balls at once. Just as it’s not juggling unless it’s three balls at the same time, it’s not SSC unless it’s stop, start, continue all done at the same time. And just as juggling two balls at once isn’t juggling, it’s not SSC if it’s just two out of the three. And just as dropping two of the three balls on the floor isn’t juggling, it’s not SSC if it’s starting, starting, starting.

Image credit – kosmolaut

A Recipe to Grow Talent

Do it for them, then explain. When the work is new for them, they don’t know how to do it. You’ve got to show them how to do it and explain everything. Tell them about your top-level approach; tell them why you focus on the new elements; show them how to make the chart that demonstrates the new one is better than the old one. Let them ask questions at every step. And tell them their questions are good ones. Praise them for their curiosity. And tell them the answers to the questions they should have asked you. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do it for them, then explain. When the work is new for them, they don’t know how to do it. You’ve got to show them how to do it and explain everything. Tell them about your top-level approach; tell them why you focus on the new elements; show them how to make the chart that demonstrates the new one is better than the old one. Let them ask questions at every step. And tell them their questions are good ones. Praise them for their curiosity. And tell them the answers to the questions they should have asked you. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do it with them, and let them hose it up. Let them do the work they know how to do, you do all the new work except for one new element, and let them do that one bit of new work. They won’t know how to do it, and they’ll get it wrong. And you’ve got to let them. Pretend you’re not paying attention so they think they’re doing it on their own, but pay deep attention. Know what they’re going to do before they do it, and protect them from catastrophic failure. Let them fail safely. And when then hose it up, explain how you’d do it differently and why you’d do it that way. Then, let them do it with your help. Praise them for taking on the new work. Praise them for trying. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Let them do it, and help them when they need it. Let them lead the project, but stay close to the work. Pretend to be busy doing another project, but stay one step ahead of them. Know what they plan to do before they do it. If they’re on the right track, leave them alone. If they’re going to make a small mistake, let them. And be there to pick up the pieces. If they’re going to make a big mistake, casually check in with them and ask about the project. And, with a light touch, explain why this situation is different than it seems. Help them take a different approach and avoid the big mistake. Praise them for their good work. Praise them for their professionalism. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Let them do it, and help only when they ask. Take off the training wheels and let them run the project on their own. Work on something else, and don’t keep track of their work. And when they ask for help, drop what you are doing and run to help them. Don’t walk. Run. Help them like they’re your family. Praise them for doing the work on their own. Praise them for asking for help. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do the new work for them, then repeat. Repeat the whole recipe for the next level of new work you’ll help them master.

Image credit — John Flannery

Where is petroleum consumed?

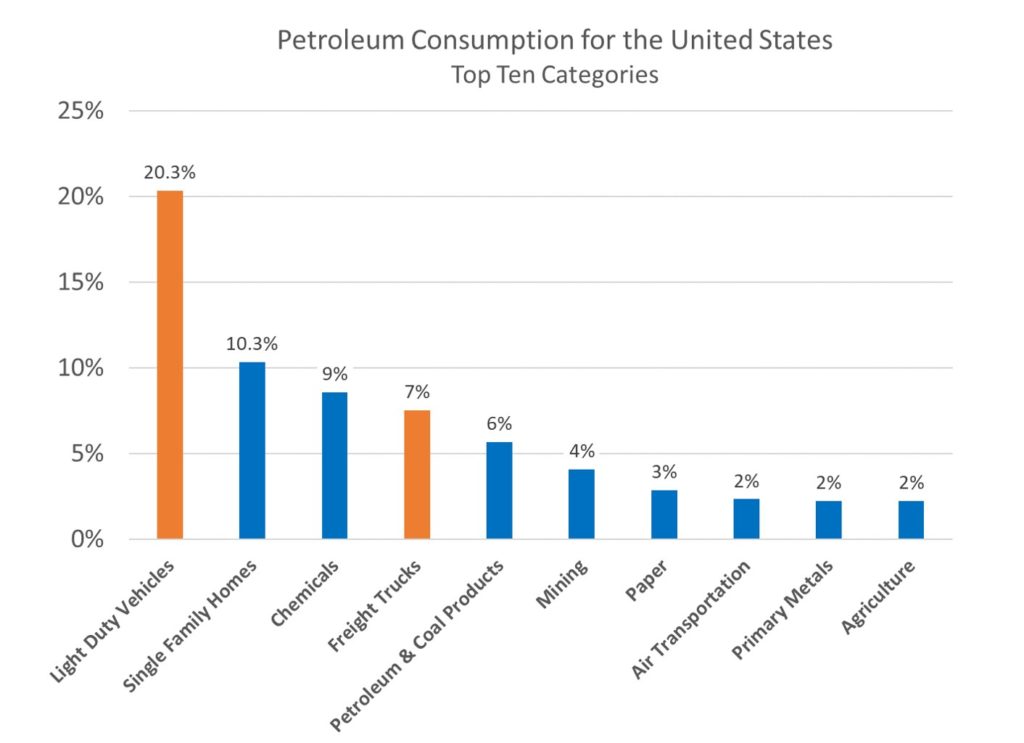

In last week’s post, I provided a chart that describes the sources of electricity for the United States. Coal is the largest source of electricity (38%) and natural gas is the next largest (25%). The largest non-carbon source is nuclear (22%) and the largest renewable sources are wind (6%) and solar (5%). The data from the chart came from Otherlab who was contracted by the Advanced Research Project Agency of the Department of Energy (ARPA-e) to review all available energy data sources and create an ultra-high resolution picture of the U.S. energy economy.

In last week’s post, I provided a chart that describes the sources of electricity for the United States. Coal is the largest source of electricity (38%) and natural gas is the next largest (25%). The largest non-carbon source is nuclear (22%) and the largest renewable sources are wind (6%) and solar (5%). The data from the chart came from Otherlab who was contracted by the Advanced Research Project Agency of the Department of Energy (ARPA-e) to review all available energy data sources and create an ultra-high resolution picture of the U.S. energy economy.

Using the same data set, I created a chart to break out the top ten categories for petroleum consumption for the United States.

The category Light-Duty Vehicles (cars, light trucks) is the largest consumer at 20% and is more than the sum of the next two categories – Single-Family Homes (10%) and Chemicals (9%).

When Light-Duty Vehicles at 20% are combined with Freight Trucks (think eighteen-wheelers) at 7%, they make up 27% of the country’s total consumption, making the Transportation sector the thirstiest. The most effective way to reduce petroleum consumption is to replace vehicles powered by internal combustion engines with electric vehicles (EVs). But there’s a catch.

As internal combustion engines diminish and EVs come online, petroleum consumption will drop and will help the planet. But, as EVs come online the demand for electricity will increase, making it even more important to replace coal and natural gas with zero-carbon sources of electricity: nuclear, hydro, wind and solar.

To save the planet, here’s what you can do. Vote for political candidates who will end federal subsidies for coal and natural gas. That single change will accelerate the adoption of wind and solar, as it will increase the existing cost advantage of wind and solar. And if that freed-up money can be reallocated to federally-funded R&D to improve the controllability of electrical grids, the change will come even sooner.

And at the state and local level, you can vote for candidates that want to make it easier for wind and solar projects to be funded.

And, lastly, you can buy an EV. You will see a much larger selection of new electric vehicles over the next year and the driving range continues to improve. Over the next year, most new EV models will be high performance and high cost, lower-cost EVs should follow soon after.

Image credit – NASA Goodard Flight Center

Time Affluence

When you have more than enough money, you have money affluence. With it, you can buy what you want, eat what you want, drive what you want, and travel where you want. But to have this unallocated money, or discretionary money, you probably need to spend a heck of a lot of time working. Climbing the ladder takes a lot of time. And once you’re at the top, you probably have a lot of commitments that pull hard on your calendar. Odds are, if you have unallocated or discretionary money (money affluence), you likely don’t have unallocated or discretionary time (time affluence).

If you have money affluence, but no time affluence, what do you really have?

To understand how much unallocated time you have, here’s an example day. You get up at 6:00 am, leave for work at 6:30, commute for an hour to arrive at work at 7:30, eat at your desk, leave work at 5:00 pm, arrive home at 6:00 and go to bed at 10:00. If this is your day, you have four hours of unallocated time per workday. I know this doesn’t include the realities of cleaning, cooking, yard work, paying bills, running errands, kids’ sporting events, and a number of other commitments, but makes the upcoming math work well and doesn’t demand we acknowledge we have little to no unallocated time.

In the contrived day described above, you’re getting enough sleep but not much else – no exercise, no time to relax during lunch. And, it’s likely you’re trading sleep for the time needed to accomplish the practical realities of daily life. But, let’s just say you have four hours of unallocated time. If you have four hours of unallocated time per day, do you think you have time affluence?

If you reduce your commute to thirty minutes, you have an extra hour of unallocated time (five). That doesn’t sound much, but you increased your unallocated time by 25%. And if you add thirty minutes of unallocated time for lunch and thirty minutes of exercise during the workday, you add another hour of unallocated time, increasing your unallocated time to six hours, or a 50% increase over the four hours of the baseline. But, to be clear, when you assign an activity of your choosing to unallocated time, it’s still unallocated time, but it may be helpful to think of it as discretionary time.

And if you tell your boss that for your first hour of work (from 7:30 to 8:30 am) there will be no meetings, no email, no phone calls, no Skype, no Slack, you increase your unallocated time by another hour, bringing your total up to seven hours, or a 75% increase in unallocated time.

As it stands, the world will take your unallocated time unless you protect it. And you won’t free up more unallocated time unless you grab your calendar and proactively squeeze out some time for yourself.

If you have money affluence, but no time affluence, you don’t have all that much.

Image credit — becosky…

All-or-Nothing vs. One-in-a-Row

All-or-nothing thinking is exciting – we’ll launch a whole new product family all at once and take the market by storm! But it’s also dangerous – if we have one small hiccup, “all” turns into “nothing” in a heartbeat. When you take an all-or-nothing approach, it’s likely you’ll have far too little “all” and far too much “nothing”.

All-or-nothing thinking is exciting – we’ll launch a whole new product family all at once and take the market by storm! But it’s also dangerous – if we have one small hiccup, “all” turns into “nothing” in a heartbeat. When you take an all-or-nothing approach, it’s likely you’ll have far too little “all” and far too much “nothing”.

Instead of trying to realize the perfection of “all”, it’s far better to turn nothing into something. Here’s the math for an all-or-nothing launch of product family launch consisting of four products, where each product will create $1 million in revenue and the probability of launching each product is 0.5 (or 50%).

1 product x $1 million x 0.5 = $500K

2 products x $1 million x 0.5 x 0.5 = $500K

3 products x $1 million x 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 = $375K

4 products x $1 million x 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 = $250K

In the all-or-nothing scheme, the launch of each product is contingent on all the others. And if the probability of each launch is 0.5, the launch of the whole product family is like a chain of four links, where each link has a 50% chance of breaking. When a single link of a chain breaks, there’s no chain. And it’s the same with an all-or-nothing launch – if a single product isn’t ready for launch, there are no product launches.

But the math is worse than that. Assume there’s new technology in all the products and there are five new failure modes that must be overcome. With all-or-nothing, if a single failure mode of a single product is a problem, there are no launches.

But the math is even more deadly than that. If there are four use models (customer segments that use the product differently) and only one of those use models creates a problem with one of the twenty failure modes (five failure modes times four products) there can be no launches. In that way, if 25% of the customers have one problem with a single failure mode, there are can be no launches. Taken to an extreme, if one customer has one problem with one product, there can be no launches.

The problem with all-or-nothing is there’s no partial credit – you either launch four products or you launch none. Instead of all-or-nothing, think “secure the launch”. What must we do to secure the launch of a single product? And once that one’s launched, the money starts to flow. And once we launch the first one, what must we do to secure the launch the second? (More money flows.) And, once we launch the third one…. you get the picture. Don’t try to launch four at once, launch a single product four times in a row. Instead of all-or-nothing, think one-in-a-row, where revenue is achieved after each launch of a single launch.

And there’s another benefit to launching one at a time. The second launch is informed by learning from the first launch. And the third is informed by the first two. With one-in-a-row, the team gets smarter and each launch gets better.

Where all-or-nothing is glamorous, one-in-a-row is achievable. Where all-or-nothing is exciting, one-in-row is achievable. And where all-or-nothing is highly improbable, one-in-a-row is highly profitable.

Image credit – Mel

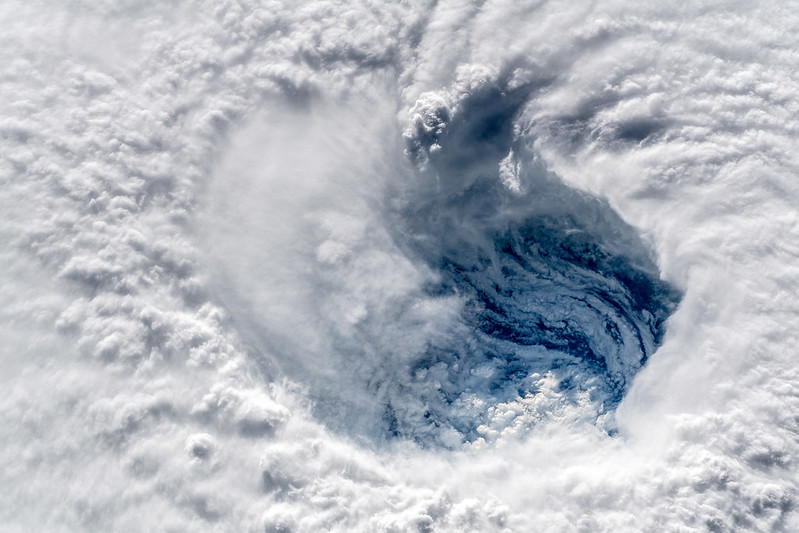

Companies, Acquisitions, Startups, and Hurricanes

If you run a company, the most important thing you can control is how you allocate your resources. You can’t control how the people in your company will respond to input, but you can choose the projects they work on. You can’t control which features and functions your customers will like, but you can choose which features and functions become part of the next product. And you can’t control if a new technology will work, but you can choose the design space to investigate. The open question – How to choose in a way that increases your probability of success?

If you want to buy a company, the most important thing you can control is how you allocate your resources. In this case, the resources are your hard-earned money and your choice is which company to buy. The open question – How to choose in a way that increases your probability of success?

If you want to invest in a startup company, the most important thing you can control is how you allocate your resources. This case is the same as the previous one – your money is the resource and the company you choose defines how you allocate your resources. This one is a little different in that the uncertainty is greater, but so is the potential reward. Again, the same open question – How to choose in a way that increases your probability of success?

Taking a step back, the three scenarios can be generalized into a category called a “system.” And the question becomes – how to understand the system in a way that improves resource allocation and increases your probability of success?

These people systems aren’t predictable in an if-A-then-B way. But they do have personalities or dispositions. They’ve got characteristics similar to hurricanes. A hurricane’s exact path cannot be forecasted, the meteorologist can use history and environmental conditions to broadly define regions where the probability of danger is higher. The meteorologist continually monitors the current state of the hurricane (the system as it is) and tracks its position over time to get an idea of its trajectory (a system’s momentum). The key to understanding where the hurricane could go next: where it is right now (current state), how it got there (how it has behaved over time), and how have other hurricanes tracked under similar conditions (its disposition). And it’s the same for systems.

To improve your understanding of how your system may respond, understand it as it is. Define the elements and how those elements interact. Then, work backward in time to understand previous generations of the system. Which elements were improved? Which ones were added? Then, like the meteorologist, start at the system’s genesis and move forward to the present to understand its path. Use the knowledge of its path and the knowledge of systems (it’s important to be the one that improves the immature elements of the system and systems follow S-curves until the S-curve flattens) to broadly define regions where the probability of success is higher.

These methods won’t guarantee success. But, they will help you choose projects, choose acquisitions, choose technologies, and choose startups in a way that increases your probability of success.

Image credit — Alexander Gerst

When Best Practice Withers Into Old Practice

When best practices get old, they turn into ruts of old practice. No, it doesn’t make sense to keep doing it this way, but we’ve done it this way in the past, we’ve been successful, and we’re going to do it like we did last time. You can misuse old practices long after they’ve withered into decrepit practices, but, ultimately, your best practices will turn into old practices and run out of gas. And then what?

It’s unskillful to wait until the wheels fall off before demonstrating a new practice – a new practice is a practice that you’ve not done before – but that’s what we mostly do. There’s immense pressure to do what we did last time because we know how it turned out last time. But when the environment around a process changes, there’s no guarantee that the output of the old process will adequately address the changing environment. What worked last time will work next time, until it doesn’t.

But there’s another reason why we don’t try new practices. We’ve never taught people how to do it. Here are some thoughts on how to try new practices.

- If you think the work can be done a better way, try a new practice, then decide if it was better. If the new practice was better, do it that way until you come up with an even better practice. Rinse and repeat.

- Don’t ask, just try the new practice.

- When you try a new practice, do it in a way that is safe to fail. (Thanks to Dave Snowden for that language.) Like before you use a new cleaning product to remove a stain on your best sweater, test the new practice in a way that won’t ruin your sweater.

- If someone asks you to use the old practice instead of trying the new practice, ask them to do it the old way and you do it the new way.

- If that someone is your boss, tell them you’re happy to do WHAT they want but you want to be the one that decides HOW to do it.

- If your boss still wants you to follow the old practice, do it the old way, do it the new way, and look for a new job because your boss isn’t worth working for.

Just because best practices were best last time, doesn’t mean they’re good practice this time.

Image credit – Dustin Moore

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski