Posts Tagged ‘Creativity’

Ask for the right work product and the rest will take care of itself.

We think we have more control than we really have. We imagine an idealized future state and try desperately to push the organization in the direction of our imagination. Add emotional energy, define a rational approach, provide the supporting rationale and everyone will see the light. Pure hubris.

We think we have more control than we really have. We imagine an idealized future state and try desperately to push the organization in the direction of our imagination. Add emotional energy, define a rational approach, provide the supporting rationale and everyone will see the light. Pure hubris.

What if we took a different approach? What if we believed people want to do the right thing but there’s something in the way? What if like a log jam in a fast-moving river, we remove the one log blocking them all? What if like a river there’s a fast-moving current of company culture that wants to push through the emotional log jam that is the status quo? What if it’s not a log at all but, rather, a Peter Principled executive that’s threatened by the very thing that will save the company?

The Peter Principled executive is a tough nut to crack. Deeply entrenched in the powerful goings on of the mundane and enabled by the protective badge of seniority, these sticks-in-the-mud need to be helped out of the way without threatening their no-longer-deserved status. Tricky business.

Rule 1: If you get into an argument with a Peter Principled executive, you’ll lose.

Rule 2: Don’t argue with Peter Principled executive.

If we want to make it easy for the right work to happen, we’ve got to learn how to make it easy for the Peter Principled executive to get out of the way. First, ask yourself why the executive is in the way. Why are they blocking progress? What’s keeping them from doing the right thing? Usually it comes down to the fear of change or the fear of losing control. Now it’s time to think of a work product that will help make the case there’s a a better way. Think of a small experiment to demonstrate a new way is possible and then run the experiment. Don’t ask, just run it. But the experiment isn’t the work product. The work product is a short report that makes it clear the new paradigm has been demonstrated, at least at small scale. The report must be clear and dense and provide objective evidence the right work happened by the right people in the right way. It must be written in a way that preempts argument – this is what happened, this is who did it, this is what it looks like and this is the benefit.

It’s critical to choose the right people to run the experiment and create the work product. The work must be done by someone in the chain of command of the in-the-way executive. Once the work product is created, it must be shared with an executive of equal status who is by definition outside the chain of command. From there, that executive must send a gracious email back into the chain of command that praises the work, praises the people who did it and praises the leader within the chain of command who had the foresight to sponsor such wonderful work.

As this public positivity filters through the organization, more people will add their praise of the work and the leaders that sponsored it. And by the time it makes it up the food chain to the executive of interest, the spider web of positivity is anchored across the organization and can’t be unwound by argument. And there you have it. You created the causes and conditions for the log jam to unjam itself. It’s now easy for the executive to get out of the way because they and their organization have already been praised for demonstrating the new paradigm. You’ve built a bridge across the emotional divide and made it easy for the executive and the status quo to cross it.

Asking for the right work product is a powerful skill. Most error on the side of complication and complexity, but the right work product is just the opposite – simple and tight. Think sledgehammer to the forehead in the form of and Excel chart where the approach is beyond reproach; where the chart can be interpreted just one way; where the axes are labeled; and it’s clear the status quo is long dead.

Business model is dead and we’ve got to stop trying to keep it alive. It’s time to break the log jam. Don’t be afraid. Create the right work product that is the dynamite that blows up the status quo and the executives clinging to it.

Image credit – Emilio Küffer

How To Design

What do they want? Some get there with jobs-to-be-done, some use Customer Needs, some swear by ethnographic research and some like to understand why before what. But in all cases, it starts with the customer. Whichever mechanism you use, the objective is clear – to understand what they need. Because if you don’t know what they need, you can’t give it to them. And once you get your arms around their needs, you’re ready to translate them into a set of functional requirements, that once satisfied, will give them what they need.

What do they want? Some get there with jobs-to-be-done, some use Customer Needs, some swear by ethnographic research and some like to understand why before what. But in all cases, it starts with the customer. Whichever mechanism you use, the objective is clear – to understand what they need. Because if you don’t know what they need, you can’t give it to them. And once you get your arms around their needs, you’re ready to translate them into a set of functional requirements, that once satisfied, will give them what they need.

What does it do? A complete set of functional requirements is difficult to create, so don’t start with a complete set. Use your new knowledge of the top customer needs to define and prioritize the top functional requirements (think three to five). Once tightly formalized, these requirements will guide the more detailed work that follows. The functional requirements are mapped to elements of the design, or design parameters, that will bring the functions to life. But before that, ask yourself if a check-in with some potential customers is warranted. Sometimes it is, but at these early stages it’s may best to wait until you have something tangible to show customers.

What does it look like? The design parameters define the physical elements of the design that ultimately create the functionality customers will buy. The design parameters define shape of the physical elements, the materials they’re made from and the interaction of the elements. It’s best if one design parameter controls a single functional requirement so the functions can be dialed in independently. At this early concept phase, a sketch or CAD model can be created and reviewed with customers. You may learn you’re off track or you may learn you’re way off track, but either way, you’ll learn how the design must change. But before that, take a little time to think through how the product will be made.

How to make it? The process variables define the elements of the manufacturing process that make the right shapes from the right materials. Sometimes the elements of the design (design parameters) fit the process variables nicely, but often the design parameters must be changed or rearranged to fit the process. Postpone this mapping at your peril! Once you show a customer a concept, some design parameters are locked down, and if those elements of the design don’t fit the process you’ll be stuck with high costs and defects.

How to sell it? The goodness of the design must be translated into language that fits the customer. Create a single page sales tool that describes their needs and how the new functionality satisfies them. And include a digital image of the concept and add it to the one-pager. Show document to the customer and listen. The customer feedback will cause you to revisit the functional requirements, design parameters and process variables. And that’s how it’s supposed to go.

Though I described this process in a linear way, nothing about this process is linear. Because the domains are mapped to each other, changes in one domain ripple through the others. Change a material and the functionality changes and so do the process variables needed to make it. Change the process and the shapes must change which, in turn, change the functionality.

But changes to the customer needs are far more problematic, if not cataclysmic. Change the customer needs and all the domains change. All of them. And the domains don’t change subtly, they get flipped on their heads. A change to a customer need is an avalanche that sweeps away much of the work that’s been done to date. With a change to a customer need, new functions must be created from scratch and old design elements must culled. And no one knows what the what the new shapes will be or how to make them.

You can’t hold off on the design work until all the customer needs are locked down. You’ve got to start with partial knowledge. But, you can check in regularly with customers and show them early designs. And you can even show them concept sketches.

And when they give you feedback, listen.

Image credit – Worcester Wired

To figure out what’s next, define the system as it is.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every morning your day starts with the body you have. You may have had a more pleasing body in the past, but that’s gone. You may have visions of changing your body into something else, but you don’t have that yet. What you do today is governed and enabled by your body as it is. If you try to lift three hundred pounds, your system as it is will either pick it up or it won’t.

Every morning your day starts with the mind you have. It may have been busy and distracted in the past and it may be calm and settled in the future, but that doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is your mind as it is. If you respond kindly, today’s mind is responsible, and if your response is unkind, today’s mind system is the culprit. Like it or not, your thoughts, feelings and actions are the result of your mind as it is.

Change always starts with where you are, and the first step is unclear until you assess and define your systems as they are. If you haven’t worked out in five years, your first step is to see your doctor to get clearance (professional assessment) for your upcoming physical improvement plan. If you’ve run ten marathons over the last ten months, your first step may be to take a month off to recover. The right next step starts with where you are.

And it’s the same with your mind. If your mind is all over the place your likely first step is to learn how to help it settle down. And once it’s a little more settled, your next step may be to use more advanced methods to settle it further. And if you assess your mind and you see it needs more help than you can give it, your next step is to seek professional help. Again, your next step is defined by where you are.

And it’s the same with business. Every morning starts with the products and services you have. You can’t sell the obsolete products you had, nor can you sell the future services you may develop. You can only sell what you have. But, in parallel, you can create the next product or system. And to do that, the first step is to take a deep, dispassionate look at the system as it is. What does it do well? What does it do poorly? What can be built on and what can be discarded? There are a number of tools for this, but more important than the tools is to recognize that the next one starts with an assessment of the one you have.

If the existing system is young and immature, the first step is likely to nurture it and support it so it can grow out of its adolescence. But the first step is NOT to lift three hundred pounds because the system-as it is-can only lift fifty. If you lift too much too early, you’ll break its back.

If the existing system is in it’s prime and has been going to the gym regularly for the last five years, its ready for three hundred pounds. Go for it! But, in parallel, it’s time to start a new activity, one that will replace the weightlifting when the system can no longer lift like it used to. Maybe tennis? But start now because to get good at tennis requires new muscles and time.

And if the existing system is ready for retirement, retire it. Difficult to do, but once there’s public acknowledgement, the retirement will take care of itself.

If you want to know what’s next, define the system as it is. The next step will be clear.

And the best time to do it is now.

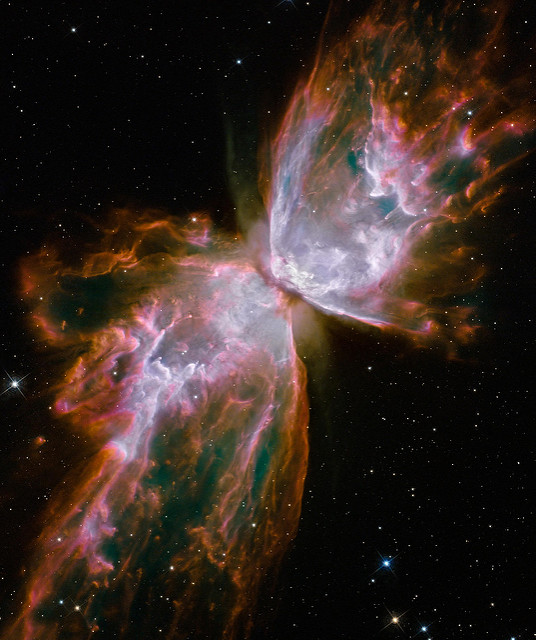

Image credit – NASA

A Little Uninterrupted Work Goes a Long Way

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

Switching costs are high, but we don’t behave that way. Once interrupted, what if it takes ten minutes to get back into the groove? What if it takes fifteen minutes? What if you’re interrupted every ten or fifteen minutes? Question: What if the minimum time block to do real thinking is thirty minutes of uninterrupted time?

Let’s assume for your average week you carve out sixty minutes of uninterrupted time each day to do meaningful work, then, doing as I propose – spending thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing something meaningful every day – increases your meaningful work by 50%. Not bad. And if for your average week you currently spend thirty contiguous minutes each day doing deep work, the proposed ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 200%. A big deal. And if you only work for thirty minutes three out of five days, the ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 400%. A night and day difference.

Question: How many times per week do you spend thirty minutes of uninterrupted time working on the most important things? How would things change if every day you spent thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing the most important work?

Great idea, but with today’s business culture there’s no way to block out ninety minutes of uninterrupted time. To that I say, before going to work, plan for thirty minutes at home. And set up a sixty-minute recurring meeting with yourself first thing every morning and do sixty minutes of uninterrupted work. And if you can’t sit at your desk without being interrupted, hold the sixty-minute meeting with yourself in a location where you won’t be interrupted. And, to make up for the thirty minutes you spent planning at home, leave thirty minutes early.

No way. Can’t do it. Won’t work.

It will work. Here’s why. Over the course of a month, you’ll have done at least 50% more real work than everyone else. And, because your work time is uninterrupted, the quality of your work will be better than everyone else’s. And, because you spend time planning, you will work on the most important things. More deep work, higher quality working conditions, and regular planning. You can’t beat that, even if it’s only sixty to ninety minutes per day.

The math works because in our normal working mode, we don’t spend much time working in an uninterrupted way. Do the math for yourself. Sum the number of minutes per week you spend working at least thirty minutes at time. And whatever the number, figure out a way to increase the minutes by 50%. A small number of minutes will make a big difference.

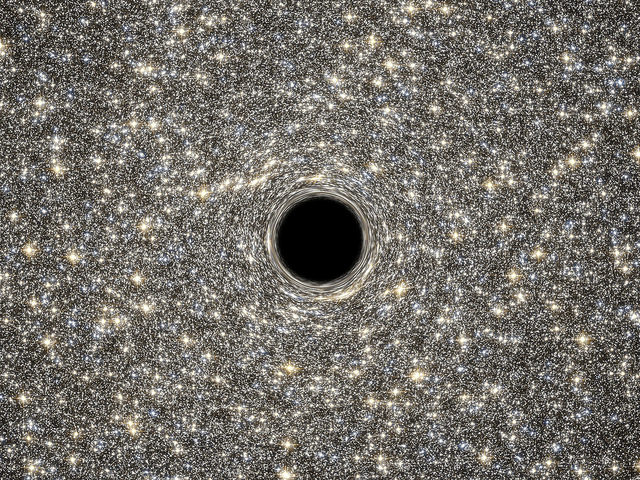

Image credit – NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Creating the Causes and Conditions for New Behavior to Grow

When you see emergent behavior that could grow into a powerful new theme, it’s important to acknowledge the behavior quickly and most publicly. If you see it in person, praise the behavior in front of everyone. Explain why you like it, explain why it’s important, explain what it could become. And as soon as you can find a computer, send an email to their bosses and copy the right-doers. Tell their bosses why you like it, tell them why it’s important, tell them what it could become.

When you see emergent behavior that could grow into a powerful new theme, it’s important to acknowledge the behavior quickly and most publicly. If you see it in person, praise the behavior in front of everyone. Explain why you like it, explain why it’s important, explain what it could become. And as soon as you can find a computer, send an email to their bosses and copy the right-doers. Tell their bosses why you like it, tell them why it’s important, tell them what it could become.

Emergent behavior is like the first shoots of a beautiful orchid that may come to be. To the untrained eye, these little green beauties can look like scraggly weeds pushing out of the dirt. To the tired, overworked leader these new behaviors can like divergence, goofing around and even misbehavior. Without studying the leaves, the fledgling orchid can be confused for crabgrass.

Without initiative there is no new behavior and without new behavior there can be no orchids. When good people solve a problem in a creative way and it goes unacknowledged, the stem of the emergent behavior is clipped. But when the creativity is watered and fertilized the seedling has a chance to grow into something more. The leaders’ time and attention provide the nutrients, the leaders’ praise provides the hydration and their proactive advocacy for more of the wonderful behavior provides the sunlight to fuel the photosynthesis.

When the company demands bushels of grain, it’s a challenge to keep an eye out for the early signs of what could be orchids in the making. But that’s what a leader must do. More often than not, this emergent behavior, this magical behavior, goes unacknowledged if not unnoticed. As leaders, this behavior is unskillful. As leaders, we’ve got to slow down and pay more attention.

When you see the magic in emergent behavior, when you see the revolution it could grow into, and when you look someone in the eye and say – “I’ve got to tell you, what you did was crazy good. What you did could turn things upside down. What you did was inspiring. Thank you.” – you get people’s attention. Not only to do you get the attention of the person you’re talking to, you get the attention of everyone within a ten-foot radius. And thirty minutes later, almost everyone knows about the emergent behavior and the warm sunshine it attracted.

And, magically, without a corporate initiative or top-down deployment, over the next weeks there will be patches of orchids sprouting under desks, behind filing cabinets, on the manufacturing floor, in the engineering labs and in the common areas.

As leaders we must make it easier for new behavior to happen. We must figure a way to slow down and pay attention so we can recognize the seeds of could-be greatness. And to be able to invest the emotional energy needed to protect the seedlings, we must be well-rested. And like we know to provide the right soil, the right fertilizer, the right watering schedule and the right sunlight, we must remember that special behavior we want to grow is a result of causes and conditions we create.

Image credit – Rosemarie Crisasfi

What’s your problem?

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

It’s important to know where a problem happens, but also when it happens.

Solutions are 90% defining and the other half is solving.

To solve a problem, you’ve got to understand things as they are.

Before you start solving a new problem, solve the one you have now.

It’s good to solve your problems, but it’s better to solve you customers’ problems.

Opportunities are problems in sheep’s clothing.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem – all the cost with none of the solution.

When you’re stumped by a problem, make it worse then do the opposite.

With problem definition, error on the side of clarity.

All problems are business problems, unless you care about society’s problems.

Odds are, your problem has been solved by someone else. Your real problem is to find them.

Define your problem as narrowly as possible, but no narrower.

Problems are not a sign of weakness.

Before adding something to solve the problem, try removing something.

If your problem involves more than two things, you have more than one problem.

The problem you think you have is never the problem you actually have.

Problems can be solved before, during or after they happen and the solutions are different.

Start with the biggest problem, otherwise you’re only getting ready to solve the biggest problem.

If you can’t draw a closeup sketch of the problem, you don’t understand it well enough.

If you have an itchy backside and you scratch you head, you still have an itch. And it’s the same with problems.

If innovation is all about problem solving and problem solving is all about problem definition, well, there you have it.

Image credit – peasap

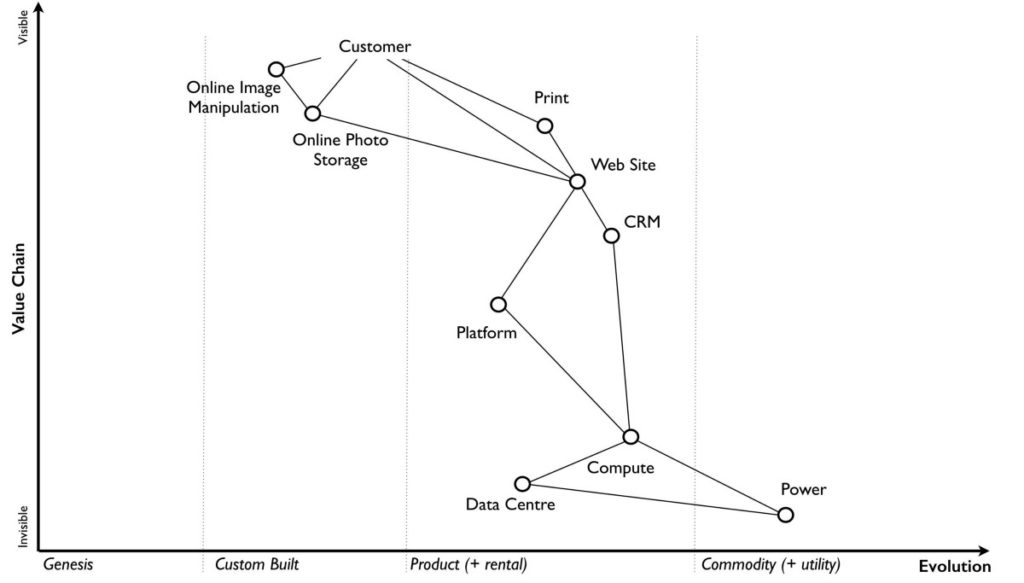

Mapping the Future with Wardley Maps

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

When there’s so many new things to work on, how do you choose the next project? When you’re lost, you look at a map. And when there is no map, you make one. The first bit of work is defined by the holes in the first revision of your map. And once the holes are filled and patched, the next work emerges from the map itself. And, in a self-similar way, the next work continually emerges from the previous work until the project finishes.

But with so much new territory, how do you choose the right new territory to map? You don’t. Before there’s a need to map new territory, you must map the current territory. What you’ll learn is there are immature areas that, when made mature, will deliver new value to customers. And you’ll also learn the mature areas that must be blown up and replaced with infant solutions that will ultimately create the next evolution of your business. And as you run thought experiments on your map – projecting advancements on the various elements – the right new territory will emerge. And here’s a hint – the right new solutions will be enabled by the newly matured elements of the map.

But how do you predict where the right new solutions will emerge? I can’t tell you that. You are the experts, not me. All I can say is, make the maps and you’ll know.

And when I say maps, I mean Wardely Maps – here’s a short video (go to 4:13 for the juicy bits).

Image credit – Simon Wardley

It’s time to stretch yourself.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

To find the right balance point, start with an assessment of your stretch level. List the number of projects you have and sum the number of major deliverables you’ve got to deliver. If you have more than three projects, you have too many. And if you think you take on more than three because you’re superhuman, you’re wrong. The data is clear – multitasking is a fallacy. If you have four projects you have too many. And it’s the same with three, but you’d think I was crazy if I suggested you limit your projects to two. The right balance point starts with reducing the number of projects you work on.

Now that you eliminated four or five projects and narrowed the portfolio down to the vital two or three, it’s time to list your major deliverables. Take a piece of paper and write them in a column down the left side of the page. And in a column next to the projects, categorize each of them as: -1 (done it before), 0 (done something similar), 1 (new to me), 2 (new to team), 3 (new to company), 5 (new to industry), 11 (new to world).

For the -1s, teach an entry level person how to do it and make sure they do it well. For the 0s, find someone who deserves a growth opportunity and let them have the work. And check in with them to make sure they do a good job. The idea is to free yourself for the stretch work.

For the 1s, find the best person in the team who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, do as they suggest but build on their work and take it to the next level.

For the 2s, find the best person in the company who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, build on their approach and make it your own.

For the 3s, do your research and find out who in your industry has done it before. Figure out how they did it and improve on their work.

For the 5s, do your research and figure out who has done similar work in another industry. Adapt their work to your application and twist it into something magical.

And for the 11s, they’re a special project category that live in rarified air and deserve a separate blog post of their own.

Start with where you are – evaluate your existing deliverables, cull them to a reasonable workload and assess your level of stretch. And, where it makes sense, stop doing work you’ve done before and start doing work you haven’t done yet. Stretch yourself, but be reasonable. It’s better to take one bite and swallow than take three and choke.

Image credit – filtran

The Evolution of New Ideas

Before there is something new to see, there is just a good idea worthy of a prototype. And before there can be good ideas there are a whole flock of bad ones. And until you have enough self confidence to have bad ideas, there is only the status quo. Creating something from nothing is difficult.

Before there is something new to see, there is just a good idea worthy of a prototype. And before there can be good ideas there are a whole flock of bad ones. And until you have enough self confidence to have bad ideas, there is only the status quo. Creating something from nothing is difficult.

New things are new because they are different than the status quo. And if the status quo is one thing, it’s ruthless in desire to squelch the competition. In that way, new ideas will get trampled simply based on their newness. But also in that way, if your idea gets trampled it’s because the status quo noticed it and was threatened by it. Don’t look at the trampling as a bad sign, look at it as a sign you are on the right track. With new ideas there’s no such thing as bad publicity.

The eureka moment is a lie. New ideas reveal themselves slowly, even to the person with the idea. They start as an old problem or, better yet, as a successful yet tired solution. The new idea takes its first form when frustration overcomes intellectual inertia a strange sketch emerges on the whiteboard. It’s not yet a good idea, rather it’s something that doesn’t make sense or doesn’t quite fit.

The idea can mull around as a precursor for quite a while. Sometimes the idea makes an evolutionary jump in a direction that’s not quite right only to slither back to it’s unfertilized state. But as the environment changes around it, the idea jumps on the back of the new context with the hope of evolving itself into something intriguing. Sometimes it jumps the divide and sometimes it slithers back to a lower energy state. All this happens without conscious knowledge of the inventor.

It’s only after several mutations does the idea find enough strength to make its way into a prototype. And now as a prototype, repeats the whole process of seeking out evolutionary paths with the hope of evolving into a product or service that provides customer value. And again, it climbs and scratches up the evolutionary ladder to its most viable embodiment.

Creating something new from scratch is difficult. But, you are not alone. New ideas have a life force of their own and they want to come into being. Believe in yourself and believe in your ideas. Not every idea will be successful, but the only way to guarantee failure is to block yourself from nurturing ideas that threaten the status quo.

Image credit – lost places

Make It Easy

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

Efficiency is overrated, especially when it interferes with effectiveness. Make it easy for effectiveness to carry the day.

You can push people off a cliff or build them a bridge to the other side. Hint – the bridge makes it easy.

Even new work is easy when people have their own reasons for doing it.

Making things easier is not easy.

Don’t tell people what to do. Make it easy for them to use their good judgement.

Set the wrong causes and conditions and creativity screeches to a halt. Set the right ones and it flows easily. Creativity is a result.

Don’t demand that people pull harder, make it easier for them to pull in the same direction.

Activity is easy to demonstrate and progress isn’t. Figure out how to make progress easier to demonstrate.

The only way to make things easier is to try to make them easier.

Image credit – Richard Hurd

The Power of Surprise

There’s disagreement on what is creative, innovative and disruptive. And there is no set of hard criteria to sort concepts into the three categories. Stepping back a bit, a lesser but still important sorting is an in-or-out categorization. Though not as good as discerning among the three, it is useful to decide if a new concept is in (one of the three) or out (not).

There’s disagreement on what is creative, innovative and disruptive. And there is no set of hard criteria to sort concepts into the three categories. Stepping back a bit, a lesser but still important sorting is an in-or-out categorization. Though not as good as discerning among the three, it is useful to decide if a new concept is in (one of the three) or out (not).

The closest thing to an acid test is assessment of the emotional response generated by a new concept. Here are some responses that I consider tell-tail signs of powerful ideas/concepts worthy of the descriptors creative, innovative, or disruptive.

When first shown, a prototype creates fear and defensiveness. The fear signals that the prototype threatens the status quo and defensiveness is objective evidence of the fear.

When first explained, a new concept creates anger and aggression. Because the concept doesn’t play by the rules, it disrespects everything holy, and the unfairness spawns indigence.

After some time, the dismissive comments about the new prototype fade and turn to discussions colored by deep sadness as the gravity of the situation hits home.

But the best leading indicator is surprise. When a test result doesn’t match your expectations, it generates surprise. And since your expectations are built on your mental models, surprising concepts contradict your mental models. And since your mental models are formed by successful experiences, prototypes that create surprise violate previous success.

If you’re surprised by a new concept, it’s worth a deeper look. If you’re not surprised, move on.

If you’re not tolerant of surprise, you should be. And if you are tolerant of surprise, it’s time to become fervent.

Image credit – Raul Pop

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski