Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

The Chief Do-the-Right-Thing Officer – a new role to protect your brand.

Our unhealthy fascination with ever-increasing shareholder value has officially gone too far. In some companies dishonesty is now more culturally acceptable than missing the numbers. (Unless, of course, you get caught. Then, it’s time for apologies.) The sacrosanct mission statement can’t save us. Even the most noble can be stomped dead by the dirty boots of profitability.

Our unhealthy fascination with ever-increasing shareholder value has officially gone too far. In some companies dishonesty is now more culturally acceptable than missing the numbers. (Unless, of course, you get caught. Then, it’s time for apologies.) The sacrosanct mission statement can’t save us. Even the most noble can be stomped dead by the dirty boots of profitability.

Though, legally, companies can self-regulate, practically, they cannot. There’s nothing to balance the one-sided, hedonistic pursuit of profitability. What’s needed is a counterbalancing mechanism of equal and opposite force. What’s needed is a new role that is missing from today’s org chart and does not have a name.

Ombudsman isn’t the right word, but part of it is right – the part that investigates. But the tense is wrong – the ombudsman has after-the-fact responsibility. The ombudsman gets to work after the bad deed is done. And another weakness – ombudsman don’t have equal-and-opposite power of the C-suite profitability monsters. But most important, and what can be built on, is the independent nature of the ombudsman.

Maybe it’s a proactive ombudsman with authority on par with the Board of Directors. And maybe their independence should be similar to a Supreme Court justice. But that’s not enough. This role requires hulk-like strength to smash through the organizational obfuscation fueled by incentive compensation and x-ray vision to see through the magical cloaking power of financial shenanigans. But there’s more. The role requires a deep understanding of complex adaptive systems (people systems), technology, patents and regulatory compliance; the nose of an experienced bloodhound to sniff out the foul; and the jaws of a pit bull that clamp down and don’t let go.

Ombudsman is more wrong than right. I think liability is better. Liability, as a word, has teeth. It sounds like it could jeopardize profitability, which gives it importance. And everyone knows liability is supposed to be avoided, so they’d expect the work to be proactive. And since liability can mean just about anything, it could provide the much needed latitude to follow the scent wherever it takes. Chief Liability Officer (CLO) has a nice ring to it.

[The Chief Do-The-Right-Thing Officer is probably the best name, but its acronym is too long.]

But the Chief Liability Officer (CLO) must be different than the Chief Innovation Officer (CIO), who has all the responsibility to do innovation with none of the authority to get it done. The CLO must have a gavel as loud as the Chief Justice’s, but the CLO does not wear the glasses of a lawyer. The CLO wears the saffron robes of morality and ethics.

Is Chief Liability Officer the right name? I don’t know. Does the CLO report to the CEO or the Board of Directors? Don’t know. How does the CLO become a natural part of how we do business? I don’t know that either.

But what I do know, it’s time to have those discussions.

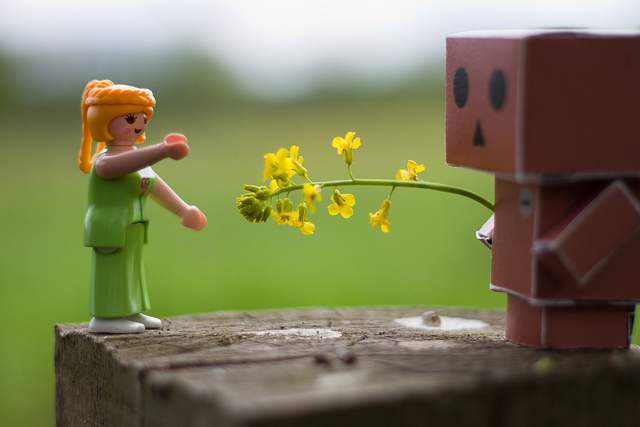

Image credit – Dietmar Temps

Solving Intractable Problems

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Intractable problems are so fundamental they are no longer seen as problems. Over the years experts simply accept these problems as constraints that must be complied with. Just as the laws of physics can’t be broken, experts behave as if these self-made constraints are iron-clad and believe these self-build walls define the viable design space. To experts, there is only viable design space or bust.

A long time ago these problems were intractable, but now they are not. Today there are new materials, new analysis techniques, new understanding of physics, new measurement systems and new business models.. But, they won’t be solved. When problems go unchallenged and constrain design space they weave themselves into the fabric of how things are done and they disappear. No one will solve them until they are seen for what they are.

It takes time to slow down and look deeply at what’s really going on. But, today’s frantic pace, unnatural fascination with productivity and confusion of activity with progress make it almost impossible to slow down enough to see things as they are. It takes a calm, centered person to spot a fundamental problem masquerading as standard work and best practice. And once seen for what they are it takes a courageous person to call things as they are. It’s a steep emotional battle to convince others their butts have been wet all these years because they’ve been sitting in a mud puddle.

Once they see the mud puddle for what it is, they must then believe it’s actually possible to stand up and walk out of the puddle toward previously non-viable design space where there are dry towels and a change of clothes. But when your butt has always been wet, it’s difficult to imagine having a dry one.

It’s difficult to slow down to see things as they are and it’s difficult to re-map the territory. But it’s important. As continuous improvement reaches the limit of diminishing returns, there are no other options. It’s time to solve the intractable problems.

Image credit – Steven Depolo

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

Don’t worry about the words, worry about the work.

Doing anything for the first time is difficult. It goes with the territory. Instead of seeing the associated anxiety as unwanted and unpleasant, maybe you can use it as an indicator of importance. In that way, if you don’t feel anxious you know you’re doing what you’ve done before.

Doing anything for the first time is difficult. It goes with the territory. Instead of seeing the associated anxiety as unwanted and unpleasant, maybe you can use it as an indicator of importance. In that way, if you don’t feel anxious you know you’re doing what you’ve done before.

Innovation, as a word, has been over used (and misused). Some have used the word to repackage the same old thing and make it fresh again, but more commonly people doing good work attach the word innovation to their work when it’s not. Just because you improved something doesn’t mean it’s innovation. This is the confusion made by the lean and Six Sigma movements – continuous improvement is not innovation. The trouble with saying that out loud is people feel the distinction diminishes the importance of continuous improvement. Continuous improvement is no less important than innovation, and no more. You need them both – like shoes and socks. But problems arise when continuous improvement is done in the name of innovation and innovation is done at the expense of continuous improvement – in both cases it’s shoes, no socks.

Coming up with an acid test for innovation is challenging. Innovation is a know-it-when-you-see-it thing that’s difficult to describe in clear language. It’s situational, contextual and there’s no prescription. [One big failure mode with innovation is copying someone else’s best practice. With innovation, cutting and pasting one company’s recipe into another company’s context does not work.] But prescriptions and recipes aside, it can be important to know when it’s innovation and when it isn’t.

If the work creates the foundation that secures your company’s growth goals, don’t worry about what to call it, just do it. If that work doesn’t require something radically new and different, all-the-better. But you likely set growth goals that were achievable regardless of the work you did. But still, there’s no need to get hung up on the label you attach to the work. If the work helps you sell to customers you could not sell to before, call it what you will, but do more of it. If the work creates a whole new market, what you call it does not matter. Just hurry up and do it again.

If your CEO is worried about the long term survivability of your company, don’t fuss over labelling your work with the right word, do something different. If you have to lower your price to compete, don’t assign another name to the work, do different work. If your new product is the same as your old product, don’t argue if it’s the result of continuous improvement or discontinuous improvement. Just do something different next time.

Labelling your work with the right word is not the most important thing. It’s far more important to ask yourself – Five years from now, if the company is offering a similar product to a similar set of customers, what will it be like to work at the company? Said another way, arguing about who is doing innovation and who is not gets in the way of doing the work needed to keep the company solvent.

If the work scares you, that’s a good indication it’s meaningful. And meaningful is good. If it scares you because it may not work, you’re definitely trying something new. And that’s good. But it’s even better if the work scares you because it just might come to be. If that’s the case, your body recognizes the work could dismantle a foundational element of your business – it either invalidates your business model or displaces a fundamental technology. Regardless of the specifics, anxiety is a good surrogate for importance.

In some cases, it can be important what you call the work. But far more important than getting the name right is doing the right work. If you want to argue about something, argue if the work is meaningful. And once a decision is reached, act accordingly. And if you want to have a debate, debate the importance of the work, then do the important work as fast as you can.

Do the important work at the expense of arguing about the words.

It’s time to make a difference.

If on the first day on your new job your stomach is all twisted up with anxiety and you’re second guessing yourself because you think you took a job that is too big for you, congratulations. You got it right. The right job is supposed to feel that way. If on your first day you’re totally comfortable because you’ve done it all before and you know how it will go, you took the job for the money. And that’s a terrible reason to take a job.

If on the first day on your new job your stomach is all twisted up with anxiety and you’re second guessing yourself because you think you took a job that is too big for you, congratulations. You got it right. The right job is supposed to feel that way. If on your first day you’re totally comfortable because you’ve done it all before and you know how it will go, you took the job for the money. And that’s a terrible reason to take a job.

You got the job because someone who knew what it would take to get it done believed you were the right one to do just that. This wasn’t charity. There was something in it for them. They needed the job done and they wanted a pro. And they chose you. The fact their stomach isn’t in knots says nothing about their stomach and everything about their belief in you. And the knots in your stomach? That ‘s likely a combination of immense desire to do a good job and an on-the-low-side belief in yourself.

If we’re not stretching we’re not learning, and if we’re not learning we’re not living. So why the nerves? Why the self doubt? Why don’t we believe in ourselves? When we look inside, we see ourselves in the moment – in the now, as we are. And sometimes when we look inside there are only re-run stories of our younger selves. It’s difficult to see our future selves, to see our own growth trajectory from the inside. It’s far easier to see a growth trajectory from the outside. And that’s what the hiring team sees – our future selves – and that’s why they hire.

This growth-stretch, anxiety-doubt seesaw is not unique to new jobs. It’s applicable right down the line – from temporary assignments, big projects and big tasks down to small tasks with tight deliverables. If you haven’t done it before, it’s natural to question your capability. But if you trust the person offering the job, it should be natural to trust their belief in you.

When you sit in your new chair for the first time and you feel queasy, that’s not a sign of incompetence it’s a sign of significance. And it’s a sign you have an opportunity to make a difference. Believe in the person that hired you, but more importantly, believe in yourself. And go make a difference.

Image credit – Thomas Angermann

The Top Three Enemies of Innovation – Waiting, Waiting, Waiting

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

With regard to time and resources, innovation’s biggest enemy is waiting. There. I said it.

There are books and articles that say innovation is too complex to do quickly, but complexity isn’t the culprit. It’s true there’s a lot of uncertainty with innovation, but, uncertainty isn’t the reason it takes as long as it does. Some blame an unhealthy culture for innovation’s long time constant, but that’s not exactly right. Yes, culture matters, but it matters for a very special reason. A culture intolerant of innovation causes a special type of waiting that, once eliminated, lets innovation to spool up to break-neck speeds.

Waiting? Really? Waiting is the secret? Waiting isn’t just the secret, it’s the top three secrets.

In a backward way, our incessant focus on productivity is the root cause for long wait times and, ultimately, the snail’s pace of innovation. Here’s how it goes. Innovation takes a long time so productivity and utilization are vital. (If they’re key for manufacturing productivity they must be key to innovation productivity, right?) Utilization of fixed assets – like prototype fabrication and low volume printed circuit board equipment – is monitored and maximized. The thinking goes – Let’s jam three more projects into the pipeline to get more out of our shared resources. The result is higher utilizations and skyrocketing queue times. It’s like company leaders don’t believe in queuing theory. Like with global warming, the theory is backed by data and you can’t dismiss queuing theory because it’s inconvenient.

One question: If over utilization of shared resources delays each prototype loop by two weeks (creates two weeks of incremental wait time) and you cycle through 10 prototype loops for each innovation project, how many weeks does it delay the innovation project? If you said 20 weeks you’re right, almost. It doesn’t delay just that one project; it delays all the projects that run through the shared resource by 20 weeks. Another question: How much is it worth to speed up all your innovation projects by 20 weeks?

In a second backward way, our incessant drive for productivity blinds us of the negative consequences of waiting. A prototype is created to determine viability of a new technology, and this learning is on the project’s critical path. (When the queue time delays the prototype loop by two weeks, the entire project slips two weeks.) Instead of working to reduce the cycle time of the prototype loop and advance the critical path, our productivity bias makes us work on non-critical path tasks to fill the time. It would be better to stop work altogether and help the company feel the pain of the unnecessarily bloated queue times, but we fill the time with non-critical path work to look busy. The result is activity without progress, and blindness to the reason for the schedule slip – waiting for the over utilized shared resource.

A company culture intolerant of uncertainty causes the third and most destructive flavor of waiting. Where productivity and over utilization reduce the speed of innovation, a culture intolerant of uncertainty stops innovation before it starts. The culture radiates negative energy throughout the labs and blocks all experiments where the results are uncertain. Blocking these experiments blocks the game-changing learning that comes with them, and, in that way, the culture create infinite wait time for the learning needed for innovation. If you don’t start innovation you can never finish. And if you fix this one, you can start.

To reduce wait time, it’s important to treat manufacturing and innovation differently. With manufacturing think efficiency and machine utilization, but with innovation think effectiveness and response time. With manufacturing it’s about following an established recipe in the most productive way; with innovation it’s about creating the new recipe. And that’s a big difference.

If you can learn to see waiting as the enemy of innovation, you can create a sustainable advantage and a sustainable company. It’s time to change expectations around waiting.

Image credit – Pulpolux !!!

Systematic Innovation

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

To put one of these innovation systems in place, the first step is to define the group that will make the decisions. Let’s call them the Decision Group, or DG for short. (By the way, this is the same group that regularly orients itself with the information steams.) And the theme of the decisions is how to deploy the organization’s resources. The decision group (DG) should be diverse so it can see things from multiple perspectives.

The DG uses the company’s mission and growth objectives as their guiding principles to set growth goals for the innovation work, and those goals are clearly placed within the context of the company’s mission.

The first action is to orient the DG in the past. Resources are allocated to analyze the product launches over the past ten years and determine the lines of ideality (themes of goodness, from the customers’ perspective). These lines define the traditional ideality (traditional themes of goodness provided by your products) are then correlated with historical profitability by sales region to evaluate their importance. If new technology projects provide value along these traditional lines, the projects are continuous improvement projects and the objective is market share gain. If they provide extreme value along traditional lines, the projects are of the dis-continuous improvement flavor and their objective is to grow the market. If the technology projects provide value along different lines and will be sold to a different customer base, the projects could be disruptive and could create new markets.

The next step is to put in place externally focused information streams which are used for continuous observation and continual orientation. An example list includes: global and regional economic factors, mergers/acquisitions/partnerships, legal changes, regulatory changes, geopolitical issues, competitors’ stock price and quarterly updates, and their new products and patents. It’s important to format the output for easy visualization and to make collection automatic.

Then, internally focused information streams are put in place that capture results from the actions of the project team and deliver them, as inputs, for observation and orientation. Here’s an example list: experimental results (technology and market-centric), analytical results (technical and market), social media experiments, new concepts from ideation sessions (IBEs), invention disclosures, patent filings, acquisition results, product commercialization results and resulting profits. These information streams indicate the level of progress of the technology projects and are used with the external information streams to ground the DG’s orientation in the achievements of the projects.

All this infrastructure, process, and analysis is put in place to help the DG make good (and fast) decisions about how to allocate resources. To make good decisions, the group continually observes the information streams and continually orients themselves in the reality of the environment and status of the projects. At this high level, the group decides not how the project work is done, rather what projects are done. Because all projects share the same resource pool, new and existing projects are evaluated against each other. For ongoing work the DG’s choice is – stop, continue, or modify (more or less resources); and for new work it’s – start, wait, or never again talk about the project.

Once the resource decision is made and communicated to the project teams, the project teams (who have their own decision groups) are judged on how well the work is executed (defined by the observed results) and how quickly the work is done (defined by the time to deliver results to the observation center.)

This innovation system is different because it is a double learning loop. The first one is easy to see – results of the actions (e.g., experimental results) are fed back into the observation center so the DG can learn. The second loop is a bit more subtle and complex. Because the group continuously re-orients itself, it always observes information from a different perspective and always sees things differently. In that way, the same data, if observed at different times, would be analyzed and synthesized differently and the DG would make different decisions with the same data. That’s wild.

The pace of this double learning loop defines the pace of learning which governs the pace of innovation. When new information from the streams (internal and external) arrive automatically and without delay (and in a format that can be internalized quickly), the DG doesn’t have to request information and wait for it. When the DG makes the resource-project decisions it’s always oriented within the context of latest information, and they don’t have to wait to analyze and synthesize with each other. And when they’re all on the same page all the time, decisions don’t have to wait for consensus because it already has. And when the group has authority to allocate resources and chooses among well-defined projects with clear linkage to company profitability, decisions and actions happen quickly. All this leads to faster and better innovation.

There’s a hierarchical set of these double learning loops, and I’ve described only the one at the highest level. Each project is a double learning loop with its own group of deciders, information streams, observation centers, orientation work and actions. These lower level loops are guided by the mission of the company, goals of the innovation work, and the scope of their projects. And below project loops are lower-level loops that handle more specific work. The loops are fastest at the lowest levels and slowest at the highest, but they feed each other with information both up the hierarchy and down.

The beauty of this loop-based innovation system is its flexibility and adaptability. The external environment is always changing and so are the projects and the people running them. Innovation systems that employ tight command and control don’t work because they can’t keep up with the pace of change, both internally and externally. This system of double loops provides guidance for the teams and sufficient latitude and discretion so they can get the work done in the best way.

The most powerful element, however, is the almost “living” quality of the system. Over its life, through the work itself, the system learns and improves. There’s an organic, survival of the fittest feel to the system, an evolutionary pulse, that would make even Darwin proud.

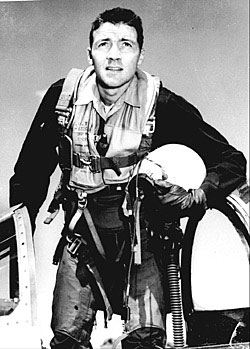

But, really, it’s Colonel John Boyd who should be proud because he invented all this. And he called it the OODA loop. Here’s his story – Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War.

Where possible, I have used Boyd’s words directly, and give him all the credit. Here is a list of his words: observe, orient, decide, act, analyze-synthesize, double loop, speed, organic, survival of the fittest, evolution.

Image attribution – U.S. Government [public domain]. by wikimedia commons.

Clarity is King

It all starts and ends with clarity. There’s not much to it, really. You strip away all the talk and get right to the work you’re actually doing. Not the work you should do, want to do, or could do. The only thing that matters is the work you are doing right now. And when you get down to it, it’s a short list.

It all starts and ends with clarity. There’s not much to it, really. You strip away all the talk and get right to the work you’re actually doing. Not the work you should do, want to do, or could do. The only thing that matters is the work you are doing right now. And when you get down to it, it’s a short list.

There’s a strong desire to claim there’s a ton of projects happening all at once, but projects aren’t like that. Projects happen serially. Start one, finish one is the best way. Sure it’s sexy to talk about doing projects in parallel, but when the rubber meets the road, it’s “one at time” until you’re done.

The thing to remember about projects is there’s no partial credit. If a project is half done, the realized value is zero, and if a project is 95% done, the realized value is still zero (but a bit more frustrating). But to rationalize that we’ve been working hard and that should count for something, we allocate partial credit where credit isn’t due. This binary thinking may be cold, but it’s on-the-mark. If your new product is 90% done, you can’t sell it – there is no realized value. Right up until it’s launched it’s work in process inventory that has a short shelf like – kind of like ripe tomatoes you can’t sell. If your competitor launches a winner, your yet-to-see-day light product over-ripens.

Get a pencil and paper and make the list of the active projects that are fully staffed, the ones that, come hell or high water, you’re going to deliver. Short list, isn’t it? Those are the projects you track and report on regularly. That’s clarity. And don’t talk about the project you’re not yet working on because that’s clarity, too.

Are those the right projects? You can slice them, categorize them, and estimate the profits, but with such a short list, you don’t need to. Because there are only a few active projects, all you have to do is look at the list and decide if they fit with company expectations. If you have the right projects, it will be clear. If you don’t, that will be clear as well. Nothing fancy – a list of projects and a decision if the list is good enough. Clarity.

How will you know when the projects are done? That’s easy – when the resources start work on the next project. Usually we think the project ends when the product launches, but that’s not how projects are. After the launch there’s a huge amount of work to finish the stuff that wasn’t done and to fix the stuff that was done wrong. For some reason, we don’t want to admit that, so we hide it. For clarity’s sake, the project doesn’t end until the resources start full-time work on the next project.

How will you know if the project was successful? Before the project starts, define the launch date and using that launch data, set a monthly profit target. Don’t use units sold, units shipped, or some other anti-clarity metric, use profit. And profit is defined by the amount of money received from the customer minus the cost to make the product. If the project launches late, the profit targets don’t move with it. And if the customer doesn’t pay, there’s no profit. The money is in the bank, or it isn’t. Clarity.

Clarity is good for everyone, but we don’t behave that way. For some reason, we want to claim we’re doing more work than we actually are which results in mis-set expectations. We all know it’s matter of time before the truth comes out, so why not be clear? With clarity from the start, company leaders will be upset sooner rather than later and will have enough time to remedy the situation.

Be clear with yourself that you’re highly capable and that you know your work better than anyone. And be clear with others about what you’re working on and what you’re not. Be clear about your test results and the problems you know about (and acknowledge there are likely some you don’t know about).

I think it all comes down to confidence and self-worth. Have the courage wear clarity like a badge of honor. You and your work are worth it.

Image credit – Greg Foster

Innovation Fortune Cookies

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If you know how it will turn out, you waited too long.

Whether you like it or not, when you start something new uncertainty carries the day.

Don’t define the idealized future state, advance the current state along its lines of evolutionary potential.

Try new things then do more of what worked and less of what didn’t.

Without starting, you never start. Starting is the most important part

Perfection is the enemy of progress, so are experts.

Disruption is the domain of the ignorant and the scared.

Innovation is 90% people and the other half technology.

The best training solves a tough problem with new tools and processes, and the training comes along for the ride.

The only thing slower than going too slowly is going too quickly.

An innovation best practice – have no best practices.

Decisions are always made with judgment, even the good ones.

image credit – Gwen Harlow

To make the right decision, use the right data.

When it’s time for a tough decision, it’s time to use data. The idea is the data removes biases and opinions so the decision is grounded in the fundamentals. But using the right data the right way takes a lot of disciple and care.

When it’s time for a tough decision, it’s time to use data. The idea is the data removes biases and opinions so the decision is grounded in the fundamentals. But using the right data the right way takes a lot of disciple and care.

The most straightforward decision is a decision between two things – an either or – and here’s how it goes.

The first step is to agree on the test protocols and measure systems used to create the data. To eliminate biases, this is done before any testing. The test protocols are the actual procedural steps to run the tests and are revision controlled documents. The measurement systems are also fully defined. This includes the make and model of the machine/hardware, full definition of the fixtures and supporting equipment, and a measurement protocol (the steps to do the measurements).

The next step is to create the charts and graphs used to present the data. (Again, this is done before any testing.) The simplest and best is the bar chart – with one bar for A and one bar for B. But for all formats, the axes are labeled (including units), the test protocol is referenced (with its document number and revision letter), and the title is created. The title defines the type of test, important shared elements of the tested configurations and important input conditions. The title helps make sure the tested configurations are the same in the ways they should be. And to be doubly sure they’re the same, once the graph is populated with the actual test data, a small image of the tested configurations can be added next to each bar.

The configurations under test change over time, and it’s important to maintain linkage between the test data and the tested configuration. This can be accomplished with descriptive titles and formal revision numbers of the test configurations. When you choose design concept A over concept B but unknowingly use data from the wrong revisions it’s still a data-driven decision, it’s just wrong one.

But the most important problem to guard against is a mismatch between the tested configuration and the configuration used to create the cost estimate. To increase profit, test results want to increase and costs wants to decrease, and this natural pressure can create divergence between the tested and costed configurations. Test results predict how the configuration under test will perform in the field. The cost estimate predicts how much the costed configuration will cost. Though there’s strong desire to have the performance of one configuration and the cost of another, things don’t work that way. When you launch you’ll get the performance of AND cost of the configuration you launched. You might as well choose the configuration to launch using performance data and cost as a matched pair.

All this detail may feel like overkill, but it’s not because the consequences of getting it wrong can decimate profitability. Here’s why:

Profit = (price – cost) x volume.

Test results predict goodness, and goodness defines what the customer will pay (price) and how many they’ll buy (volume). And cost is cost. And when it comes to profit, if you make the right decision with the wrong data, the wheels fall off.

Image credit – alabaster crow photographic

Prototypes Are The Best Way To Innovate

If you’re serious about innovation, you must learn, as second nature, to convert your ideas into prototypes.

If you’re serious about innovation, you must learn, as second nature, to convert your ideas into prototypes.

Funny thing about ideas is they’re never fully formed – they morph and twist as you talk about them, and as long as you keep talking they keep changing. Evolution of your ideas is good, but in the conversation domain they never get defined well enough (down to the nuts-and-bolts level) for others (and you) to know what you’re really talking about. Converting your ideas into prototypes puts an end to all the nonsense.

Job 1 of the prototype is to help you flesh out your idea – to help you understand what it’s all about. Using whatever you have on hand, create a physical embodiment of your idea. The idea is to build until you can’t, to build until you identify a question you can’t answer. Then, with learning objective in hand, go figure out what you need to know, and then resume building. If you get to a place where your prototype fully captures the essence of your idea, it’s time to move to Job 2. To be clear, the prototype’s job is to communicate the idea – it’s symbolic of your idea – and it’s definitely not a fully functional prototype.

Job 2 of the prototype is to help others understand your idea. There’s a simple constraint in this phase – you cannot use words – you cannot speak – to describe your prototype. It must speak for itself. You can respond to questions, but that’s it. So with your rough and tumble prototype in hand, set up a meeting and simply plop the prototype in front of your critics (coworkers) and watch and listen. With your hand over your mouth, watch for how they interact with the prototype and listen to their questions. They won’t interact with it the way you expect, so learn from that. And, write down their questions and answer them if you can. Their questions help you see your idea from different perspectives, to see it more completely. And for the questions you cannot answer, they the next set of learning objectives. Go away, learn and modify your prototype accordingly (or build a different one altogether). Repeat the learning loop until the group has a common understanding of the idea and a list of questions that only a customer can answer.

Job 3 is to help customers understand your idea. At this stage it’s best if the prototype is at least partially functional, but it’s okay if it “represents” the idea in clear way. The requirement is prototype is complete enough for the customer can form an opinion. Job 3 is a lot like Job 2, except replace coworker with customer. Same constraint – no verbal explanation of the prototype, but you can certainly answer their direction questions (usually best answered with a clarifying question of your own such as “Why do you ask?”) Capture how they interact with the prototype and their questions (video is the best here). Take the data back to headquarters, and decide if you want to build 100 more prototypes to get a broader set of opinions; build 1000 more and do a small regional launch; or scrap it.

Building a prototype is the fastest, most effective way to communicate an idea. And it’s the best way to learn. The act of building forces you to make dozens of small decisions to questions you didn’t know you had to answer and the physical nature the prototype gives a three dimensional expression of the idea. There may be disagreement on the value of the idea the prototype stands for, but there will be no ambiguity about the idea.

If you’re not building prototypes early and often, you’re not doing innovation. It’s that simple.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski