Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Letting Yourself Be Inspired by Others

When you try something new, check to see who has done something similar. Decompose their design approach. What were they trying to achieve? What outcome were they looking for? Who were their target customers? Do this for at least three existing designs – three real examples that are for sale today.

When you try something new, check to see who has done something similar. Decompose their design approach. What were they trying to achieve? What outcome were they looking for? Who were their target customers? Do this for at least three existing designs – three real examples that are for sale today.

Here’s a rule to live by: When trying something new, don’t start from scratch.

What you are trying to achieve is unique, but has some commonality with existing solutions. The outcome you are looking for is unique, but it’s similar to outcomes others have tried to achieve. Your target customers are unique, but some of their characteristics are similar to the customers of the solutions you’ll decompose.

Here’s another rule: There are no “clean sheet” sheet designs, so don’t try to make one.

There was an old game show called Name That Tune, where contestants would try to guess the name of a song by hearing just a few notes. The player wins when they can name the tune with the *fewest* notes. And it’s the same with new designs – you want to provide a novel customer experience using the fewest new notes.

A rule: Reuse what you can, until you can’t.

Because the customer is the one who decides if your new offering offers them new value, the novel elements of your design don’t have to look drastically different in a side-by-side comparison way. But the novel elements of your offering do have to make a significant difference in the customer’s life. With that said, however, it can be helpful if the design element responsible for the novel goodness is visually different from the existing alternatives. But if that’s not the case, you can add a non-functional element to the novelty-generating element to make it visible to the customer. For example, you could add color, or some type of fingerprint, to the novel element of the design so that customers can see what creates the novelty for them. Then, of course, you market the heck out of the new color or fingerprint.

A rule: It’s better to make a difference in a customer’s life than, well, anything else.

Don’t be shy about learning from what other companies have done well. That’s not to say you should violate their patents, but it’s a compliment when you adopt some of their best stuff. Learn from them and twist it. Understand what they did and abstract it. See the best in two designs and combine them. See the goodness in one domain and bring it to another.

Doing something for the first time is difficult, why not get inspiration from others and make it easier?

“two of a kind” by anathea is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The One Thing That’s Always in the Way

If you could get another good job at the drop of a hat, how would you work differently? Would you speak your mind or bite your tongue?

If you could get another good job at the drop of a hat, how would you work differently? Would you speak your mind or bite your tongue?

If you didn’t care about getting a promotion, would you succumb to groupthink or dissent?

If your ego didn’t get in the way, would you stop following the worn-out recipe and make a new one?

If you don’t judge yourself by the number of people who work for you, would your work be better? Would you choose to work on different projects? How do you feel about that?

If you knew your time at the company was finite, how would your contribution change? Who would you stop working with? Who would you start working with? Wouldn’t that feel good?

If you didn’t care about your yearly rating, wouldn’t your rating improve?

If you cared more about helping others, wouldn’t your talents (and the returns) be multiplied?

If your time horizon was doubled, wouldn’t work on projects that are important at the expense of those that are urgent?

If your ego didn’t block you from working on projects that might fail, wouldn’t you work on projects that could obsolete your best work?

If you cared about the long-term success of the company, wouldn’t you work more with young people to get them ready for the next decade?

If you cared solely about doing the right projects in the right way, wouldn’t you help your best team members move to the most important projects, even if that meant they worked for someone else?

If you cared about helping people develop, would you formalize their development areas and help them grow, or take the easy route and let them flounder?

If you didn’t care about getting the credit, how would you and your work be different? Would the company be better for it? How about your happiness?

If you declined every other meeting and just read the meeting minutes, would that be a problem? And even if there are no meeting minutes to read, don’t you think that you’d get along just fine? And don’t you think you’d get more done?

What would you have to change to work more often with young people?

What would you have to change so your best people could be moved to the most important projects?

What would you have to change so you’d dissent when that’s what’s needed?

What would you have to change to develop others, even if it cost you a promotion?

What would you have to change so you could ditch the urgent projects and start the meaningful ones?

What would you have to change so you could spend more time developing young talent?

What would you have to change so you could attend fewer meetings and make more progress?

What would you have to change so you could work on the most outlandish projects?

What’s in the way of looking inside and figuring out how to live differently?

If you were able to change, who would you start work with? Who would you stop working with? Which projects would you start and which would you stop? Which meetings would you skip? Who are the three young people you’d help grow?

If you were able to change, would you be better for it? And how about the people that work with you? And how about your family? And wouldn’t your company be better for it?

So I ask you – What’s in the way? And what are you going to do about it?

“Evie looking in the mirror” by Ambernectar 13 is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

When is too much too much?

When you’re out of gas, you’re out of gas. And there are no two ways about it, the last year has emptied our tanks. And when your tank is empty, it’s empty. When there’s nothing left, there’s nothing left. But what if you’re asked for more?

When you’re out of gas, you’re out of gas. And there are no two ways about it, the last year has emptied our tanks. And when your tank is empty, it’s empty. When there’s nothing left, there’s nothing left. But what if you’re asked for more?

What is the mechanism to communicate that the workload is too much? How do you tell your boss that you can’t produce as you did before the pandemic because, well, you’re emotionally exhausted? How do you tell company leadership that this is not the time to layer on more corporate initiatives and elevate the importance of accountability? And if you do deliver those messages, will there be ramifications to your career? No ramifications you say? Then why do most feel overwhelmed yet say nothing?

How might we conserve our emotional energy to focus on what’s important? And what if the company thinks business continuity is most important and you think your family’s continuity is most important? What’s a caring parent to do? How about a loving spouse? How about an exhausted employee who wants desperately to contribute to the cause? And what if you’re all three? And what about your mental health?

If you can help someone, help them. If you don’t have the energy for that, tell them you know they are suffering and sit with them. They don’t expect you to fix it, they just want you to sit with them.

If you’re part of a team, check in with your teammates. Again, no need to try and fix them, just listen to them. Really listen. Listen so you can repeat what you heard in your own words. There’s power in being heard.

If you’re in a position to tell company leadership that people are living on the edge, tell them. If you’re not in that position, find someone who might be and ask them to pass it along. Tell them it’s important. Tell them it’s dire.

And when you go home to your family, tell them you’re exhausted and tell them you love them. And you’re doing your best. And tell them you know they’re doing their best, too. And tell them you love them.

“Too much stress got ahold of this @acsabudhabi student!” by ToGa Wanderings is licensed under CC BY 2.0

It’s not a race to complete the most tasks.

If you have too much to do, that means you have more tasks than time. And because time is limited, the only way out is to change how you think about your task list.

If you have too much to do, that means you have more tasks than time. And because time is limited, the only way out is to change how you think about your task list.

If you have too many tasks, you haven’t yet decided which tasks are important and which are less important. Until you rank tasks by importance, you’ll think you have too many.

When you have more tasks than you can handle, you don’t. You can handle what you can handle. No problem there. What you have are expectations that are out of line with the reality of what one person can get done in a day. What you can get done is what you can get done. Then end. The thing to understand about task lists is they don’t give a damn about work content. They are perfectly happy to get longer when new tasks are added, regardless of your capacity to get them done. That’s just how it goes with task lists. Why do you think it’s okay to judge yourself negatively for a growing task list?

Just because a task is on a task list doesn’t mean it must get done. A task list is just a tool to keep track of tasks, nothing more. A task list helps you assess which tasks are most important so you can work on the right one until it’s time to go home.

Here are some tips on how to handle your tasks.

Identify your top three most important tasks and work on the most important one until it’s complete.

When the most important task is complete, move each task one step closer to the top and work on the most important one until it’s complete.

If you’re not willing to finish a task, don’t start it. (Think switching cost.)

Don’t start a task before finishing one. (No partial for a half-done task.)

The fastest way to complete a task is to simply remove it from the list. (Full credit for deleting a task of low importance.)

Complete the tasks you can complete and leave the rest. (And no self-judgment or guilt.)

It’s not about completing the most tasks. It’s about completing the most important ones.

Image credit — kosmolaut

Thinking Dynamically

If you’re asked to do cost reduction, before doing that work, ask for objective evidence that the work to grow the top line is adequately staffed. You can’t secure your company’s future through cost reduction, so before you spend time and effort to grow the bottom line, make sure the work to grow the top line is more than fully staffed. Without top-line growth, cost reduction is nothing more than a race to the bottom.

If you’re asked to do cost reduction, before doing that work, ask for objective evidence that the work to grow the top line is adequately staffed. You can’t secure your company’s future through cost reduction, so before you spend time and effort to grow the bottom line, make sure the work to grow the top line is more than fully staffed. Without top-line growth, cost reduction is nothing more than a race to the bottom.

If you’re asked to do more of what was done last time, before doing that work, look back and plot how that line of goodness has improved over time. If the goodness over time is flat (it hasn’t increased), the technology is mature, there’s nothing left, and you should improve something else (a new line of goodness). If the goodness continues to increase over time, ask customers if it’s already good enough. Do this by asking if they’d pay more for more goodness. If they won’t pay more, it’s already good enough. Stop work on that tired, old line of goodness and work on a new one. If goodness over time is still increasing and customers will pay more, teach someone else how to improve that line of goodness so you can establish the next line of goodness which will be needed when the old one gets tired.

If you’re asked to make your product do more, before doing that work, figure out if the planet will be better off if your product does more. If the planet will frown if your product does more, make your product do less with far less. In that way, your customers will get a bit less, but they’ll use far fewer resources and the planet will smile. And when the planet smiles, so will the stockholders of the company that provides less with far less.

If you’re asked to improve a specific line of goodness, before doing that work, look to see if competitive technologies are also improving on that same line of goodness. If their improvement slope is steeper than yours, you will be overtaken. Find a new line of goodness to improve, or buy the dominant company in that’s making progress with the competitive technology. Don’t wait, or sooner rather than later, they’ll buy you.

If you’re asked to make your product do more, before doing that work, look at the byproducts that will increase and how that relates to the regulatory standards. If those nasty byproducts are (or will be) regulated, future improvements will be blocked by regulatory limits. You can argue about when those limits will be a problem, but you can’t argue that those regulatory limits will ultimately take you out by the knees. It’s a tough pill to swallow, but it’s time to look to a new technology because your existing one will soon be outlawed.

Everything changes. Nothing is static. Technologies get better, then it’s difficult to make the next improvement. Competitors get better, then it’s difficult to be better than them. Environmental constraints get tighter, then you’re legally blocked from improvements that violate those constraints. Last year’s solutions become obsolete. Last year’s analysis tools become obsolete. Last year’s best materials are no longer best. And last year’s manufacturing best processes are no longer best. That’s just how it works.

Before you allocate precious resources to do what you did last time, spend a little time to analyze the situation in a dynamic sense. What changed since last time? Has the regulatory environment changed? Have competitors made improvements? Have new competitors emerged with new technologies? Has your legacy technology run out of gas or does it still have legs? Have new tools come of age and who is using them?

Everything has a half-life – technologies, products, services, tools, processes, business models, and people. When new things are come to be, the only thing you can guarantee is that time will run out and they will run their course. Even if your business model has been successful, it has a half-life and it will die.

Success causes us to think statically, but the universe behaves dynamically. The trick is to use the resources created by our success to sow the seeds that must grow into the solutions of an uncertain future. The best time to plant a tree was fifteen years ago, and the next best time to plant one is today.

Image credit — Matthew Dillon

To increase profits, make the planet smile.

What if the most profitable thing you could do was work that reduced the rise in the earth’s temperature? What if it was most profitable to reduce CO2 emissions, improve water quality or generate renewable energy? Or what if it was most profitable to do work that indirectly made the planet smile?

What if the most profitable thing you could do was work that reduced the rise in the earth’s temperature? What if it was most profitable to reduce CO2 emissions, improve water quality or generate renewable energy? Or what if it was most profitable to do work that indirectly made the planet smile?

What if while your competitors greenwashed their products and you radically reduced the environmental impacts of yours? And what if the market would pay more for your greener product? And what if your competitors saw this and disregarded the early warning signs of their demise? This is what I call a compete-with-no-one condition. This is where your competitors eat each other’s ankles in a race to the bottom while you raise prices and sell more on a different line of goodness – environmental goodness. This is where you compete against no one because you’re the only one with products that make the planet smile.

The problem with an environmentally-centric, compete-with-no-one approach is you have to put yourself out there and design and commercialize new products based on this “unproven” goodness. In a world of profits through cost, quality and speed, you’ve got to choose profits through reduced CO2, improved water quality and renewable energy. Why would anyone pay more for a more environmentally responsible product when its price is higher than the ones that work well and pollute just as much as they did last year?

When the Toyota Prius hybrid first arrived on the market, it cost more than traditional cars and its performance was nothing special. Yet it sold. Yes, it had radically improved fuel economy, but the fuel savings didn’t justify the higher price, yet it sold. Competitors advertised that the Prius hybrid didn’t make financial sense, yet it sold. With the Prius hybrid, Toyota took an environmentally-centric, compete-with-no-one approach. They made little on each vehicle or even lost money, but they did it anyway. They did the most important thing. They started.

The Toyota Prius hybrid wasn’t a logical purchase, it was an emotional one. People bought them to make a statement about themselves – I drive a funny-shaped car that gets great gas mileage, I’m environmentally responsible, and I want you to know that. And as other companies scoffed, Toyota created a new category and owned the whole thing.

And, slowly, as Toyota improved the technology and reduced their costs, the price of the Prius dropped and they sold more. And then all the other manufacturers jumped into the race and tried to catch up. And while everyone else cut their teeth on high volume manufacturing a hybrid vehicle, Toyota accelerated.

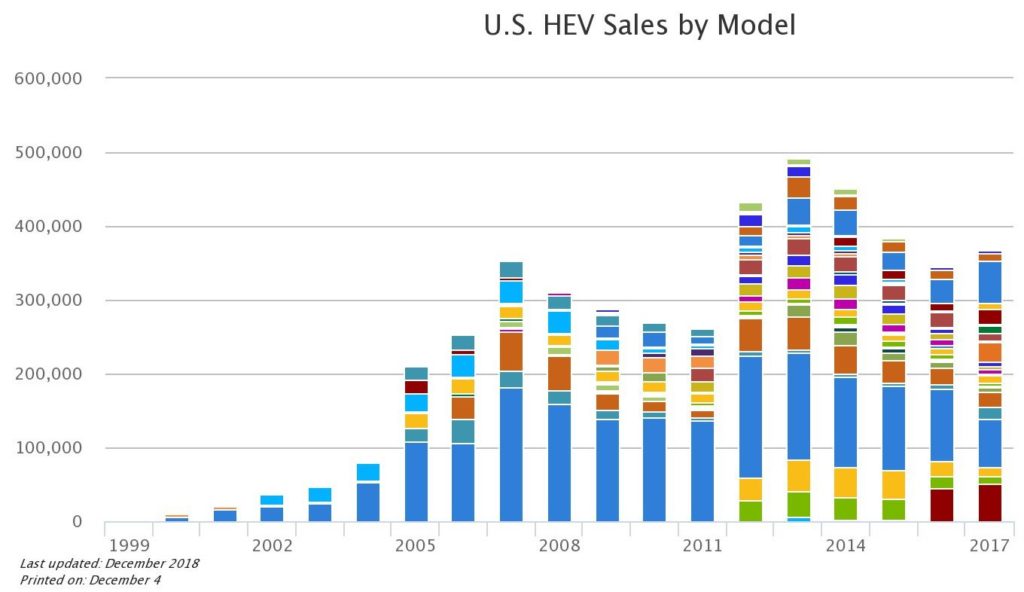

Below is a chart of hybrid electric vehicles (hev) sold in the US from 2000 to 2017. Each color represents a different model and the Toyota Prius hybrid is represented by the tall blue segment of each year’s stacked bar. In 2000, Toyota sold 5,562 Prius hybrids (60% of all hevs). In 2005, they sold 107,897 Prius hybrids, 17,989 Highlander hybrids and 20,674 Lexus hybrids for a total of 209,711 hybrids (69% of all hevs). In 2007, they sold 181,221 Prius and five other hybrid models for a total of 228,593 (65% of all hevs). In 2017, sold 15 hybrid models and the nearest competitor sold 4 models. The reduction from 2008 to 2011 is due to reduced gas prices. (Here’s a link to the chart.)

The success of the Prius vehicle set off the battery wars which set the stage for the plug-in hybrids (larger batteries) and all-electric vehicles (still larger batteries). At the start, the Prius didn’t make sense in a race-to-the-bottom way, but it made sense to people that wanted to make the planet smile. It cost more, and it sold. And that was enough for Toyota to make profits with a more environmentally friendly product. No, Prius didn’t save the planet, but it showed companies that it’s possible to make profits while making the planet smile (a bit). And it made it safe for companies to pursue the next generation of environmentally-friendly vehicles.

The only way to guarantee you won’t make more profits with environmentally responsible products is to believe you won’t. And that may be okay unless one of your companies believes it is possible.

Here’s a thought experiment. Put yourself ten years into the future. There is more CO2 in the atmosphere, the earth is warmer, sea levels are higher, water is more polluted and renewable energy is far cheaper. Are your sales higher if your product creates more CO2, or less? Are your sales higher if your product heats the earth, or cools it? Are your sales higher if your product pollutes water, or makes it cleaner? Are your sales higher because you bet against renewable energy, or because you embraced it? Are your sales higher because you made the planet frown, or smile?

Now, with your new perspective, bring yourself back to the present and do what it takes to increase sales ten years from now. Your future self, your children, their children, and the planet will thank you.

Image credit saeru

When it rains, don’t blame the clouds.

When it rains, you get wet. It doesn’t matter if you get mad at the clouds, you still get wet. And if you curse the sky, you still get wet. So, why the anger and cursing? Do you really think the clouds see you’re outside and choose to rain on you? Do you think the sky is out to get you?

When someone aims snarl words at you, you get angry because you take it personally. But, their harsh words are about them, not you. And they’re not aiming at you; you just happen to be near them when the words jump out of their mouth. Like the clouds don’t choose to rain on you; you just happen to be under them when their water comes out.

It’s much easier to accept that the clouds are not out to get you because the clouds are not people. It takes a lot of personal work to let someone’s snarl words pass through you. But if a screen door can do it, so can you.

The screen door lets the breeze pass through. It doesn’t flap or flutter, it just lets the hot air pass. It’s there when it’s time to block the bugs but not there when it’s time to let the breeze pass. The screen door doesn’t take the breeze personally, it lets it pass through.

When someone snarls at you, be a screen door and let those words pass through. Try to remember their words are about them, not you. When the snarl words are swirling, don’t be there emotionally. Don’t own their words; don’t accept their gift. Don’t be there emotionally.

But after the storm of words dissipates, be there for them. Ask them what’s bothering them. Listen. Try to understand. Empathize. I bet you’ll learn what’s really going on with them.

In the heat of the moment, it’s easy to take things personally. But if you visualize them as a cloud, maybe you can weather the storm they are trying to create. Or, it may be easier to imagine yourself as a screen door and let their words pass.

Either way, cloud or screen door, it takes practice. And either way, it can make a big difference in your happiness.

The Importance of Helping Others

When someone you care about needs help, help them. Even when you have other things to do, help them anyway.

When someone you care about needs help, help them. Even when you have other things to do, help them anyway.

When people ask you for help, it’s a sign they trust you. And they trust you because you’ve demonstrated over time that your words and behaviors match. You said you’d do A and you did A. You said you’d do B and you did B. And because you’ve made that investment in them over the years, they value you and your time. And because they value you and your time, they don’t want to be a burden to you. And if they think you’ve got a lot on your plate, they may downplay the importance of their need for help and say things like “It’s no big deal.” or “It’s not that important.” or “It’s okay, it can wait.”.

However unforcefully, they asked for help because the need it. It was a big deal for them to ask because they know you are busy. And their willingness to dismiss or delay, is not a sign of unimportance of their need. Rather, it’s a show of their respect for you and your time. They desperately need your help, but care enough about you to give you any opportunity to say no. Those are the telltale signs that it’s time to stop what you’re doing and help them. This is the time when you can make the biggest difference. Stop immediately and help them.

Your helping starts with listening and listening starts with getting ready to listen. Smile and tell them that this little chat deserves a coffee or cold drink and walk with them to get a beverage. This critical step serves several functions. It makes it clear you are willing to make time for them and puts them at ease; it gives you time to let go of what you were working on so you can give them your full attention; and it gives you a little time to put yourself in their shoes so you will be able to hear what really going on.

By making time for them, you’ve already helped them. Someone they trust and respect stopped what they were doing and made time for them. They’re already standing two inches taller. And, with a clear head, you actively listen and understand, they grow another two inches. Often, just telling their story is enough for them to solve their own problem. In that way, your helping starts and ends with listening. And other times, they don’t really want you to solve their problem, they just want you to listen and empathize. And when they’re looking for more, rather than giving them answers, they’d rather you ask clarifying questions and paraphrase to demonstrate understanding.

You can’t do this for everyone, but you can do it for the people you care about most. Sure, you have to scamper to catch up on your own work, but it’s worth it. By helping them you help yourself twice – once from happiness that comes from helping someone you care about and twice from the joy that comes from watching them do the same for people they care about.

Our work is difficult and our lives are busy. But our work gets easier when we get and give help. And even with our always-on, always-connected culture, life is about building meaningful connections. How can your life be too busy for that?

Maybe we have it backwards. What if meaningful connections aren’t something we create so we can do our work better? What if we think of work as nothing more than a mechanism to create meaningful connections?

Image credit – Jlhopgood.

How mature is your technology?

As a technologist it’s important to know the maturity of a technology. Like people, technologies are born, they become children, then adolescents, then adults and then they die. And like with people, the character and behavior of technologies change as they grown and age. A fledgling technology may have a lot of potential, but it can’t pay the mortgage until it matures. To know a technologies level of maturity is to know when it’s premature to invest, to know when it’s time to invest, to know when to ride it for all it’s worth and time to let it go.

As a technologist it’s important to know the maturity of a technology. Like people, technologies are born, they become children, then adolescents, then adults and then they die. And like with people, the character and behavior of technologies change as they grown and age. A fledgling technology may have a lot of potential, but it can’t pay the mortgage until it matures. To know a technologies level of maturity is to know when it’s premature to invest, to know when it’s time to invest, to know when to ride it for all it’s worth and time to let it go.

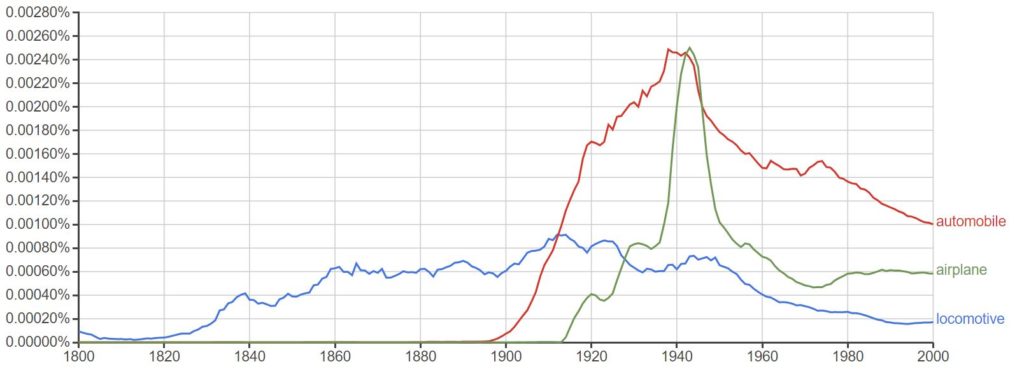

Google has a tool called Ngram Viewer that performs keyword searches of a vast library of books and returns a plot of how frequently the word was found in the books. Just type the word in the search line, specify the years (1800-2007) and look at the graph.

Below is a graph I created for three words: locomotive, automobile and airplane. (Link to graph.) If each word is assumed to represent a technology, the graph makes it clear when authors started to write about the technologies (left is earliest) and how frequently it was used (taller is more prevalent). As a technology, locomotives came first, as they were mentioned in books as early as 1800. Next came the automobile which hit the books just before 1900. And then came the airplane which first showed itself in about 1915.

In the 1820s the locomotives were infants. They were slow, inefficient and unreliable. But over time they matured and replaced the Pony Express. In the late 1890s the automobiles were also infants and also slow, inefficient and unreliable. But as they matured, they displaced some of the locomotives. And the airplanes of 1915 were unsafe and barely flight-worthy. But over time they matured and displaced the automobiles for the longest trips.

[Side note – the blip in use of the word in 1940s is probably linked to World War II.]

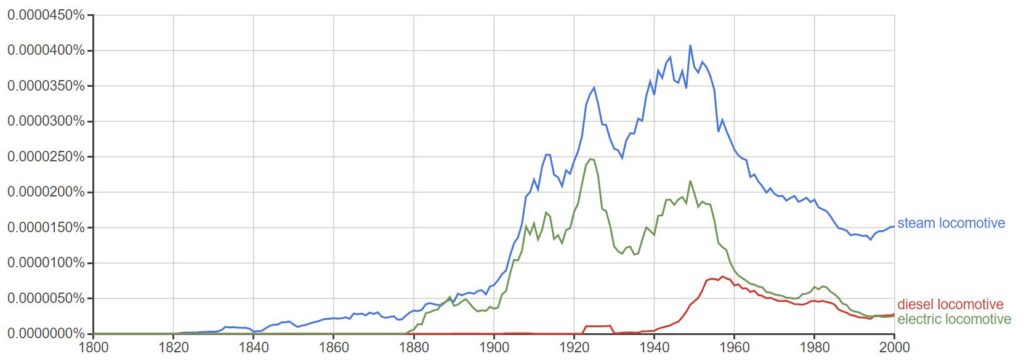

But for the locomotive, there’s a story with a story. Below is a graph I created for: steam locomotive, diesel locomotive and electric locomotive. After it matured in the 1840s and became faster and more efficient, the steam locomotive displaced the wagon trains. But, as technology likes to do, the electric locomotive matured several decades after it’s birth in 1880 and displaced it’s technological parent the steam locomotive. There was no smoke with the electric locomotive (city applications) and it did not need to stop to replenish it’s coal and water. And then, because turn-about is fair play, the diesel locomotive displaced some of the electric locomotives.

The Ngram Viewer tool isn’t used for technology development because books are published long after the initial technology development is completed and there is no data after 20o7. But, it provides a good example of how new technologies emerge in society and how they grow and displace each other.

To assess the maturity of the youngest technologies, technologists perform similar time-based analyses but on different data sets. Specialized tools are used to make similar graphs for patents, where infant technologies become public when they’re disclosed in the form of patents. Also, special tools are used to analyze the prevalence of keywords (i.e., locomotives) for scientific publications. The analysis is similar to the Ngram Viewer analysis, but the scientific publications describe the new technologies much sooner after their birth.

To know the maturity of the technology is to know when a technology has legs and when it’s time to invent it’s replacement. There’s nothing worse than trying to improve a mature technology like the diesel locomotive when you should be inventing the next generation Maglev train.

Image credit – kanegen

Even entrepreneurial work must fit with the brand.

To meet ever-increasing growth objectives, established companies want to be more entrepreneurial. And the thinking goes like this – launch new products and services to create new markets, do it quickly and do it on a shoestring. Do that Lean Startup thing. Build minimum viable prototypes (MVPs), show them to customers, incorporate their feedback, make new MVPs, show them again, and then thoselaunch.

To meet ever-increasing growth objectives, established companies want to be more entrepreneurial. And the thinking goes like this – launch new products and services to create new markets, do it quickly and do it on a shoestring. Do that Lean Startup thing. Build minimum viable prototypes (MVPs), show them to customers, incorporate their feedback, make new MVPs, show them again, and then thoselaunch.

For software products, that may work well, largely because it takes little time to create MVPs, customers can try the products without meeting face-to-face and updating the code doesn’t take all that long. But for products and services that require new hardware, actual hardware, it’s a different story. New hardware takes a long time to invent, a long time to convert into an MVP, a long time to show customers and a long time to incorporate feedback. Creating new hardware and launching quickly in an entrepreneurial way don’t belong in the same sentence, unless there’s no new hardware.

For hardware, don’t think smartphones, think autonomous cars. And how’s that going for Google and the other software companies? As it turns out, it seems that designing hardware and software are different. Yes, there’s a whole lot of software in there, but there’s also a whole lot of new sensor systems (hardware). And, what complicates things further is that it’s all packed into an integrated system of subsystems where the hardware and software must cooperate to make the good things happen. And, when the consequences of a failure are severe, it’s more important to work out the bugs.

And that’s the rub with entrepreneurship and an established brand. For quick adoption, there’s strong desire to leverage the established brand – GM, Ford, BMW – but the output of the entrepreneurial work (new product or service) has to fit with the brand. GM can’t launch something that’s half-baked with the promise to fix it later. Ford can come out with a new app that is clunky and communicates intermittently with their hardware (cars) because it will reflect poorly on all their products. In short, they’ll sell fewer cars. And BMW can’t come out with an entrepreneurial all-electric car that handles poorly and is slow off the start. If they do, they’ll sell fewer cars. If you’re an established company with an established brand, the output of your entrepreneurial work must fit with the established brand.

If you’re a software startup, launch it when it’s half-baked and fix it later, as long as no one will die when it flakes out. And because it’s software, iterate early and often. And, there’s no need to worry about what it will do to the brand, because you haven’t created it yet. But if you’re a hardware startup, be careful not to launch before it’s ready because you won’t be able to move quickly and you’ll be stuck with your entrepreneurial work for longer than you want. Maybe, even long enough to sink the brand before it ever learned to swim. Developing hardware is slow. And developing robust hardware-software systems is far slower.

If you’re an established company with an established brand, tread lightly with that Lean Startup thing, even when it’s just software. An entrepreneurial software product that works poorly can take down the brand, if, of course, your brand stands for robust, predictable, value and safety. And if the entrepreneurial product relies on new hardware, be doubly careful. If it goes belly-up, it will be slow to go away and will put a lot of pressure on that wonderful brand you took so long to build.

If you’re an established brand, it may be best to buy your entrepreneurial products and services from the startups that took the risk and made it happen. That way you can buy their successful track record and stand it on the shoulders of your hard-won brand.

Image credit – simpleinsomnia

With novelty, less can be more.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

To create something new, don’t look to the future. Instead, sit in the present and understand the system as it is. Define the major elements and what they do. Define connections among the elements. Create a functional diagram using blocks for the major elements, using a noun to name each block, and use arrows to define the interactions between the elements, using a verb to label each arrow. This sounds like a complete waste of time because it’s assumed that everyone knows how the current state system behaves. The system has been the backbone of our success, of course everyone knows the inputs, the outputs, who does what and why they do it.

I have created countless functional models of as-is systems and never has everyone agreed on how it works. More strongly, most of the time the group of experts can’t even create a complete model of the as-is system without doing some digging. And even after three iterations of the model, some think it’s complete, some think it’s incomplete and others think it’s wrong. And, sometimes, the team must run experiments to determine how things work. How can you imagine an idealized future state when you don’t understand the system as it is? The short answer – you can’t.

And once there’s a common understanding of the system as it is, if there’s a call for a clean sheet design, run away. A call for a clean sheet design is sure fire sign that company leadership doesn’t know what they’re doing. When creating something new it’s best to inject the minimum level of novelty and reuse the rest (of the system as it is). If you can get away with 1% novelty and 99% reuse, do it. Novelty, by definition, hasn’t been done before. And things that have never been done before don’t happen quickly, if they happen at all. There’s no extra credit for maximizing novelty. Think of novelty like ghost pepper sauce – a little goes a long way. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a clean sheet design and do the opposite.

Greenfield designs should be avoided like the plague. The existing system has coevolved with its end users so that the system satisfies the right needs, the users know how to use the system and they know what to expect from it. In a hand-in-glove way, the as-is system is comfortable for end users because it fits them. And that’s a big deal. Any deviation from baseline design (novelty) will create discomfort and stress for end users, even if that novelty is responsible for the enhancement you’re trying to deliver. Novelty violates customer expectations and violating customer expectations is a dangerous game. Again, when you think novelty, think ghost peppers. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a green field and do the opposite.

This approach is not incrementalism. Where you need novelty, inject it. And where you don’t need it, reuse. Design the system to maximize new value but do it with minimum novelty. Or, better still, offer less with far less. Think 90% of the value with 10% of the cost.

Image credit – Laurie Rantala

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski