Archive for the ‘Part Count Reduction’ Category

DFA and Lean – A Most Powerful One-Two Punch

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

Still not convinced parts are the key? Take a look at the seven wastes and add “of parts” to the end of each one. Here is what it looks like:

- Waste of overproduction (of parts)

- Waste of time on hand – waiting (for parts)

- Waste in transportation (of parts)

- Waste of processing itself (of parts)

- Waste of stock on hand – inventory (of parts)

- Waste of movement (from parts)

- Waste of making defective products (made of parts)

And look at Suzaki’s cartoons. (Click them to enlarge.) What do you see? Parts.

Take out the parts and the waste is not reduced, it’s eliminated. Let’s do a thought experiment, and pretend your product had 50% fewer parts. (I know it’s a stretch.) What would your factory look like? How about your supply chain? There would be: fewer parts to ship, fewer to receive, fewer to move, fewer to store, fewer to handle, fewer opportunities to wait for late parts, and fewer opportunities for incorrect assembly. Loosen your thinking a bit more, and the benefits broaden: fewer suppliers, fewer supplier qualifications, fewer late payments; fewer supplier quality issues, and fewer expensive black belt projects. Most importantly, however, may be the reduction in the transactions, e.g., work in process tracking, labor reporting, material cost tracking, inventory control and valuation, BOMs, routings, backflushing, work orders, and engineering changes.

However, there is a big problem with the thought experiment — there is no one to design out the parts. Since company leadership does not thrust greatness on the design community, design engineers do not have to participate in lean. No one makes them do DFA-driven part count reduction to compliment lean. Don’t think you need the design community? Ask your best manufacturing engineer to write an engineering change to eliminates parts, and see where it goes — nowhere. No design engineer, no design change. No design change, no part elimination.

It’s staggering to think of the savings that would be achieved with the powerful pairing of DFA and lean. It would go like this: The design community would create a low waste design on which the lean community would squeeze out the remaining waste. It’s like the thought experiment; a new product with 50% fewer parts is given to the lean folks, and they lean out the low waste value stream from there. DFA and lean make such a powerful one-two punch because they hit both sides of the waste equation.

DFA eliminates parts, and lean reduces waste from the ones that remain.

There are no technical reasons that prevent DFA and lean from being done together, but there are real failure modes that get in the way. The failure modes are emotional, organizational, and cultural in nature, and are all about people. For example, shared responsibility for design and manufacturing typically resides in the organizational stratosphere – above the VP or Senior VP levels. And because of the failure modes’ nature (organizational, cultural), the countermeasures are largely company-specific.

What’s in the way of your company making the DFA/lean thought experiment a reality?

Product Design – the most powerful (and missing) element of lean

Lean has been beneficial for many companies, helping improve competitiveness and profitability. But, lean has not been nearly as effective as it can be because there is a missing ingredient – product design. Where lean can reduce the waste of making and moving parts, product design can eliminate the parts altogether; where lean can reduce setup times for big machines, product design can change the parts so they no longer need the big machines; where lean can reduce inventory, product design can eliminate it by designing out parts; where lean can make the supply chain more efficient, product design can radically shorten it by designing out the long lead time elements.

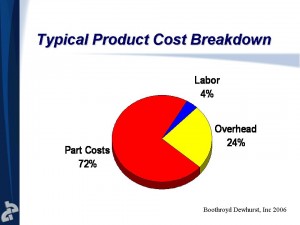

The power of product design is even more evident when considering the breakdown of product cost. Here is some data from Nick Dewhurst taken from multiple-hundred DFMA analyses showing the typical cost breakdown of products.

Of the three buckets of cost, material cost is by far the largest 74%, and this is where product development shines. Product design can eliminate 40 to 50% of material cost resulting in radical cost savings. Lean cannot. I will go a bit further and say that material cost reductions are largely off limits to the lean folks since it requires fundamental product changes.

Side note – Probably most surprising about cost breakdown data is labor cost is only 4%. Why we move our manufacturing to “low cost countires” to chase 50% labor reductions to net a whopping 2% cost reduction is beyond me, but that’s for a different post.

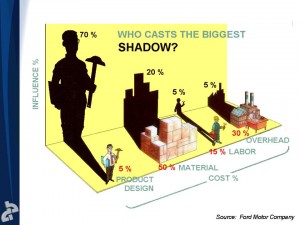

Let’s face it – material cost reduction is where it’s at, and lean does not have the toolbox to reduce material cost. There’s no mystery here. What is mysterious, however, is that companies looking to survive at all costs are not pulling the biggest lever at their disposal – product design. Here is a bit of old data from Ford showing that Product Design has the biggest lever on cost. We’ve know this for a long time, but we still don’t do it.

Clearly, the best approach of is to combine the power of product design with lean. It goes like this: the engineers design a low cost, low waste product that is introduced to the production line, and the lean folks improve efficiency and reduce cost from there. We’ve got the lean part down, but not the product design part.

There are two things in the way of designing low cost, low waste products in a way that helps take lean to the next level. First, product development teams don’t know how to do the work. To overcome this, train them in DFMA. Second, and most important, company leaders don’t give the product development teams the tools, time, and training to do the work. Company leaders won’t take the time to do the work because they think it will delay product launches. Also, they don’t want to invest in the tools and training because the cost is too high, even though a little math shows the investment is more than paid back with the first product launch. To fix that, educate them on the methods, the resource needs, and the savings.

Good luck.

Design for Manufacture and Assembly Helps OEM Reduce Warranty Costs, Boost Profits

Design2Part Magazine published a good article on DFMA’s ability to cut costs, labor, floor space and improve global competitiveness.

An expert from the article:

Five-year implementation of DFMA software creates strong business model for improving global competitiveness

“We started with a vision to make radical improvements in both product performance and product economies,” stated Mike Shipulski, Hypertherm’s director of engineering. “Hypertherm met both of these goals by aggressively applying Boothroyd Dewhurst’s software within our existing programs for robust design and lean manufacturing. We found their product simplification software made it easy for us to improve a product’s performance-to-cost ratio. Moreover, we learned that DFMA ideas and financial estimates also lead to profound savings beyond labor and part cost, creating a domino effect ‘downstream’ in operational areas of our organization.”

Redesigns get radical improvements using DFMA

Redesigns get radical improvements using DFMA

Hypertherm, Inc. of Hanover, NH, is among the world’s foremost manufacturers of plasma arc cutting equipment. Founded in 1968 with a staff of two, the company today has 750 employees, with subsidiaries, sales offices, and distributors in multiple countries. All technology development, product development, and manufacturing is done in the Hanover area.

View of the new HyPerformance Plasma HPR130 plasma cutter from Hypertherm. The company used Design for Manufacture and Analysis (DFMA) methodology to radically redesign — and improve — the system’s manufacturability. In the new plasma cutter, system subassemblies took 45% to 89% less time to put together. Assembly floor space opened up by 40%. Warranty cost went down 83%. Cost savings amounted to $5 million over 24 months, which helped the company achieve record earnings and its highest profit sharing on record.

Hypertherm’s products range from lightweight, manual plasma cutting equipment to highly mechanized systems that operate with CNC cutting machines. Its advanced technology serves a global customer base in every industry that depends on quality and reliability in high-temperature metal cutting, such as shipbuilding, construction, farm equipment, rail car and truck manufacture, and plant maintenance.

Recently, Hypertherm engineers tackled a project of mammoth proportions when they remodeled the company’s highly successful HD3070 plasma cutting system — and ultimately created the new HyPerformance Plasma HPR130 plasma cutter. Before the redesign project, the HD3070 sold well and was widely regarded as a standard for robust, high-precision cutting in the industry. Hypertherm wanted to make the product even better.

“We started with a vision to make a radical improvement in product performance coupled with a radical reduction in product cost,” says Mike Shipulski, director of engineering for Hypertherm. He believed that using the methodology of Design for Manufacture and Analysis (DFMA) would help identify unnecessary parts, highlight assembly difficulties that Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski