Archive for the ‘Cost Savings’ Category

DFA Saves More than Six Sigma and Lean

I can’t believe everyone isn’t doing Design for Assembly (DFA), especially in these tough economic times. It’s almost like CEOs really don’t want to grow stock price. DFA, where the product design is changed to reduce the cost of putting things together, routinely achieves savings of 20-50% in material cost, and the same for labor cost. And the beauty of the material savings is that it falls right to the bottom line. For a product that costs $1000 with 60% material cost ($600) and 10% profit margin ($100), a 10% reduction in material cost increases bottom line contribution by 60% (from $100 to $160). That sounds pretty good to me. But, remember, DFA can reduce material cost by 50%. Do that math and, when you get up off the floor, read on.

Unfortunately for DFA, the savings are a problem – they’re too big to be believed. That’s right, I said too big. Here’s how it goes. An engineer (usually an older one who doesn’t mind getting fired, or a young one who doesn’t know any better) brings up DFA in a meeting and says something like, “There’s this crazy guy on the web writing about DFA who says we can design out 20-50% of our material cost. That’s just what we need.” A pained silence floods the room. One of the leaders says something like, “Listen, kid, the only part you got right is calling that guy crazy. We’re the world leaders in our field. Don’t you think we would have done that already if it was possible? We struggle to take out 2-3% material cost per year. Don’t talk about 20-50% because is not possible.” DFA is down for the count.

Also unfortunate is the name – DFA. You’ve got to admit DFA doesn’t roll off the tongue like six sigma which also happens to sound like sex sigma, where DFA does not. I think we should follow the lean sigma trend and glom some letters onto DFA so it can ride the coat tails of the better known methodologies. Here are some letters that could help:

Lean DFA; DFA Lean; Six Sigma DFA; Six DFA Sigma (this one doesn’t work for me); Lean DFA Sigma

Its pedigree is also a problem – it’s not from Toyota, so it can’t be worth a damn. Maybe we should make up a story that Deming brought it to Japan because no one in the west would listen to him, and it’s the real secret behind Toyota’s success. Or, we can call it Toyota DFA. That may work.

Though there is some truth to the previous paragraphs, the main reason no one is doing DFA is simple:

No one is asking the design community to do DFA.

Here is the rationalization: The design community is busy and behind schedule (late product launches). If we bother them with DFA, they may rebel and the product will never launch. If we leave them alone and cross our fingers, maybe things will be all right. That is a decision made in fear, which, by definition, is a mistake.

The design community needs greatness thrust upon them. It’s the only way.

Just as the manufacturing community was given no choice about doing six sigma and lean, so should the design community be given no choice about doing DFA.

No way around it, the first DFA effort is a leap of faith. The only way to get it off the ground is for a leader in the organization to stand up and say “I want to do DFA.” and then rally the troops to make it happen.

I urge you to think about DFA in the same light as six sigma or lean: If your company had a lean or six sigma project that would save you 20-50% on your product cost, would you do it? I think so.

Who in your organization is going to stand up and make it happen?

Product Design – the most powerful (and missing) element of lean

Lean has been beneficial for many companies, helping improve competitiveness and profitability. But, lean has not been nearly as effective as it can be because there is a missing ingredient – product design. Where lean can reduce the waste of making and moving parts, product design can eliminate the parts altogether; where lean can reduce setup times for big machines, product design can change the parts so they no longer need the big machines; where lean can reduce inventory, product design can eliminate it by designing out parts; where lean can make the supply chain more efficient, product design can radically shorten it by designing out the long lead time elements.

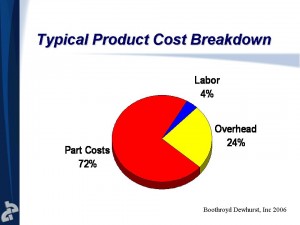

The power of product design is even more evident when considering the breakdown of product cost. Here is some data from Nick Dewhurst taken from multiple-hundred DFMA analyses showing the typical cost breakdown of products.

Of the three buckets of cost, material cost is by far the largest 74%, and this is where product development shines. Product design can eliminate 40 to 50% of material cost resulting in radical cost savings. Lean cannot. I will go a bit further and say that material cost reductions are largely off limits to the lean folks since it requires fundamental product changes.

Side note – Probably most surprising about cost breakdown data is labor cost is only 4%. Why we move our manufacturing to “low cost countires” to chase 50% labor reductions to net a whopping 2% cost reduction is beyond me, but that’s for a different post.

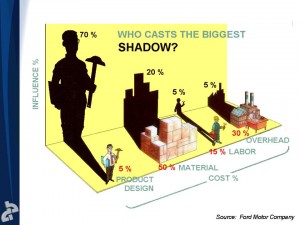

Let’s face it – material cost reduction is where it’s at, and lean does not have the toolbox to reduce material cost. There’s no mystery here. What is mysterious, however, is that companies looking to survive at all costs are not pulling the biggest lever at their disposal – product design. Here is a bit of old data from Ford showing that Product Design has the biggest lever on cost. We’ve know this for a long time, but we still don’t do it.

Clearly, the best approach of is to combine the power of product design with lean. It goes like this: the engineers design a low cost, low waste product that is introduced to the production line, and the lean folks improve efficiency and reduce cost from there. We’ve got the lean part down, but not the product design part.

There are two things in the way of designing low cost, low waste products in a way that helps take lean to the next level. First, product development teams don’t know how to do the work. To overcome this, train them in DFMA. Second, and most important, company leaders don’t give the product development teams the tools, time, and training to do the work. Company leaders won’t take the time to do the work because they think it will delay product launches. Also, they don’t want to invest in the tools and training because the cost is too high, even though a little math shows the investment is more than paid back with the first product launch. To fix that, educate them on the methods, the resource needs, and the savings.

Good luck.

Out of the recession — top line or bottom line approach?

I have been watching the news and listening to the pundits, and, apparently, we are steaming out of the great recession and the manufacturing flywheel is nearing full speed.

I have been watching the news and listening to the pundits, and, apparently, we are steaming out of the great recession and the manufacturing flywheel is nearing full speed.

As we all know, that’s a bunch of crap. Many manufactures are still in survival mode where cost cutting has crossed into the ridiculous; where the best talent has been cut; and where the product development flywheel is motionless. We are far from coming out of this thing, and the bad stuff we had to do to survive will take time to undo.

However, some companies are considering options to accelerate themselves out of the soup. They are asking the big question – what is the fastest way out?

To me, the fastest way out is all about three things: product, product, product — do you have the right products coming to market? Or, if not, how can you get your product development flywheel moving so the right products hit the market as quickly as possible? But, what are the attributes of the “right product”?

I think there are two components of the right product: the top line component and the bottom line component. The top line component (which drives top line growth) is all about function and features. More function equals increased sales through market share and price. The bottom line component (bottom line growth) is all about cost. Pretty basic. But, if your resources are limited (like most of us) and can improve only one, which should you improve?

Bottom line cost reduction is not glamorous, but the balance sheet improvment is surprisingly good. Let me give an example. Product A is an existing product that sells for $1000 and it costs you $800 to produce, providing $200 profit per unit. You spend your product development resources on a bottom line effort and reduce product cost by 20%. Still selling for $1000 but with a cost of $640 (0.8 * $800), profit dollars increase by 80% ($360 vs. $200). Not bad especially since sales have not increased.

Top line growth has a strong emotional component which energizes people, and the upside potential is huge. Here is an example using the same product as above. Product A still sells for $1000, costs you $800, and you make $200 per unit. You spend your product development resources on a top line project to add better functionality and more features. Because you don’t have time to address the bottom line component, your costs go up 10% (to $880). But, you do get the function and features you wanted, and the market can support a 10% price increase to $1100. Profit per unit is up 10% t0 $220 ($1100 – $880). Your engineering really came through and the market likes your new product and sales increase by 20%. With all that, profit dollars increase by 32% ($220*1.2 = $264 vs. $200).

Clearly the examples are contrived to illustrate a point: bottom line cost reduction is powerful and so are top line sales growth and price increase. And the best answer is not to choose between top line and bottom line components. It makes a lot of sense to do a little of both, because it’s the fastest way out of the soup.

Engage product design in DFMA now; achieve 30 to 50% later

I wrote an article on the level of savings when product designers are engaged in DFMA.

Here is an excerpt:

This month, Shipulski details the company’s lean product-design efforts as he issues a “call to action” for lean manufacturers everywhere to involve their product-design teams.

Why should the manufacturing engineering community care about engaging the product design community in pursuits such as design for manufacturing (DFM) and design for assembly (DFM)? The answer is simple—to make (and save) money

Leading manufacturers cite upfront design creates significant downstream savings

Results from a new survey show that upfront design using DFMA methods creates significant savings in operational cost — downstream savings.

An exerpt from the survey:

Sixty-eight percent of a survey group, including Fortune 400 companies, measured an increase in production throughput, and 47 percent an increase in profit per unit of factory floor space, after applying Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DFMA®) techniques to their organizations’ supply chains. A roundtable discussion of these and other results from the questionnaire, conducted by Boothroyd Dewhurst, Inc., is now available.

Respondents included Dell, Motorola, TRW Automotive, Raytheon, MDS Analytical Technologies, Magna Intier Automotive Seating and other leading North American manufacturers. Some participants also contributed to a candid roundtable discussion about applying design simplification and early costing to Lean and Six Sigma programs, along with the opportunities missed by industry in measuring financial best practices.

Measuring DFMA Savings

Wes Iverson, Managing Editor of Automation World, wrote a good artcle on DFMA’s ability to cut product cost, reduce part count, and save assembly floor space.

Measuring DFMA Savings — Automation World

An expert from his article:

When a Hypertherm team led by Shipulski designed a major new plasma cutting machine several years ago, the team was able to reduce the number of parts required to about 700, down from around 1,400 in the previous generation design. The result was a machine that took about four hours to build, compared to 10 hours for the previous unit, enabling Hypertherm to hit its 35 percent cost reduction target for the system.

Design for Manufacture and Assembly Helps OEM Reduce Warranty Costs, Boost Profits

Design2Part Magazine published a good article on DFMA’s ability to cut costs, labor, floor space and improve global competitiveness.

An expert from the article:

Five-year implementation of DFMA software creates strong business model for improving global competitiveness

“We started with a vision to make radical improvements in both product performance and product economies,” stated Mike Shipulski, Hypertherm’s director of engineering. “Hypertherm met both of these goals by aggressively applying Boothroyd Dewhurst’s software within our existing programs for robust design and lean manufacturing. We found their product simplification software made it easy for us to improve a product’s performance-to-cost ratio. Moreover, we learned that DFMA ideas and financial estimates also lead to profound savings beyond labor and part cost, creating a domino effect ‘downstream’ in operational areas of our organization.”

Redesigns get radical improvements using DFMA

Redesigns get radical improvements using DFMA

Hypertherm, Inc. of Hanover, NH, is among the world’s foremost manufacturers of plasma arc cutting equipment. Founded in 1968 with a staff of two, the company today has 750 employees, with subsidiaries, sales offices, and distributors in multiple countries. All technology development, product development, and manufacturing is done in the Hanover area.

View of the new HyPerformance Plasma HPR130 plasma cutter from Hypertherm. The company used Design for Manufacture and Analysis (DFMA) methodology to radically redesign — and improve — the system’s manufacturability. In the new plasma cutter, system subassemblies took 45% to 89% less time to put together. Assembly floor space opened up by 40%. Warranty cost went down 83%. Cost savings amounted to $5 million over 24 months, which helped the company achieve record earnings and its highest profit sharing on record.

Hypertherm’s products range from lightweight, manual plasma cutting equipment to highly mechanized systems that operate with CNC cutting machines. Its advanced technology serves a global customer base in every industry that depends on quality and reliability in high-temperature metal cutting, such as shipbuilding, construction, farm equipment, rail car and truck manufacture, and plant maintenance.

Recently, Hypertherm engineers tackled a project of mammoth proportions when they remodeled the company’s highly successful HD3070 plasma cutting system — and ultimately created the new HyPerformance Plasma HPR130 plasma cutter. Before the redesign project, the HD3070 sold well and was widely regarded as a standard for robust, high-precision cutting in the industry. Hypertherm wanted to make the product even better.

“We started with a vision to make a radical improvement in product performance coupled with a radical reduction in product cost,” says Mike Shipulski, director of engineering for Hypertherm. He believed that using the methodology of Design for Manufacture and Analysis (DFMA) would help identify unnecessary parts, highlight assembly difficulties that Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski