Posts Tagged ‘Product Development Engine’

Change the plan or stay the course?

Plans are good, until they’re not. The key is knowing when to stay the course and when to adjust the plan.

Plans are good, until they’re not. The key is knowing when to stay the course and when to adjust the plan.

The time horizons for strategic plans or corporate initiatives can range from two to five years. To ensure we create the best plans, we assign the work to our best people, we provide them with the best information, and we ask them to use their best judgment. As input, we assess market fundamentals, technology trends, customer segments, our internal talent, our partners, our infrastructure, and our processes. We then set revenue targets and create project plans and resource allocation plans to realize the revenue goals. And then it’s go time.

We initiate the projects, work the plans, and report regularly on the progress. If the progress meets the monthly goal, we keep going. And if the progress doesn’t meet the monthly goal, we keep going. We invested significant time and effort into the plan, and it can be politically difficult, if not bad for your career, to change the plan. It takes confidence and courage to call for a change to a strategic plan or a corporate initiative. But two to five years is a long time, and things can (and do) change over the life of a plan.

A plan is created with the best knowledge available at the time. We assess the environment and use the knowledge to set the financial requirements for the plan. When the environment and requirements change, the plan should change.

Before considering any changes, if we learn that the assumptions used to create the plan are invalid, the plan should change. For example, if the resource allocation is insufficient, the timelines should be extended, resources should be added, or the scope of the work should be reduced. I think changing the plan is responsible management, and I think it’s irresponsible management to stay the course.

The environment can change in many ways. Here are five categories of change: tariffs, competition, internal talent (key people move on), new customer learning, and new technical learning (e.g., more technical risk than anticipated). Significant changes in any of these categories should trigger an assessment of the plan’s viability. This is not a sign of weakness. This is responsible management. And if the change in the environment invalidates the plan’s assumptions, the plan should change.

The specification (revenue targets) for the plans can change. There are at least two flavors of change: an increase in revenue goals or a shorter timeline to achieve revenue goals, which are usually caused by changes to the environment. And when there’s a need for more revenue or to deliver it sooner, the plans should be assessed and changed. Again, I think this is good management practice and not a sign of failure or weakness. When we realize the plan won’t meet the new specification, we should modify the plan.

When we learn the assumptions are wrong, we should change the plan. When the environment changes, we should change the plan. And when the specification changes, we should change the plan.

Image credit — Charlie Day

Fight Dilution!

With new product development projects, there is no partial credit. If you’re less than 100% done, there are zero sales. 90% done, zero sales. 95% done, zero sales. We all understand the concept, but our behavior often contradicts our understanding. You have too many projects, and our focus on efficiency is to blame.

With new product development projects, there is no partial credit. If you’re less than 100% done, there are zero sales. 90% done, zero sales. 95% done, zero sales. We all understand the concept, but our behavior often contradicts our understanding. You have too many projects, and our focus on efficiency is to blame.

Under the banner of efficiency, we run too many projects in parallel, and our limited resources become spread too thinly over too many projects. Project timelines grow, launch dates are pushed out, and revenue generation is delayed. And because there’s a shortfall in revenue, we start more projects to close the gap. That’s funny.

In short, we’ve morphed Start, Stop, Continue into Start, Start, Start.

Here’s a process to help you stop starting and start finishing.

Open a spreadsheet and list all your projects for the year. At the top of the column, list the projects you’ve completed. Below the completed projects, list your active projects, and below them, list your future (not yet started) projects. Highlight the completed projects and the active projects, and set the print area. Then, select “print on both sides of the page.” When you print the file, the future projects will be printed on the back of the page. This will help you focus on the completed and active projects and block you from trying to start a project before finishing one.

Now, go back to the top of the spreadsheet and select the completed projects and change the font to “strike through.” This will allow you to read the project names and remind yourself of the projects you completed. You can use this list to justify a strong performance rating at your upcoming performance review.

Skip down to the active projects and categorize them as fully staffed or partially staffed. Change the font color to red for the partially staffed projects and move them to the second page with the future projects. Print out the spreadsheet.

The completed projects will be at the top of the page in strike-through font, and the short list of fully staffed projects is listed below them in normal font. On the back of the page, the partially staffed projects are listed in red, and the future projects are listed below them. And now you’re ready to realize the power of the two-sided printout.

Step 1. Ignore the projects on the back of the page (under-staffed and yet to be started projects). They’re still on the do-do list, but they’ll wait patiently on the back of the page until resources are freed up and allocated.

Step 2. Finish the fully staffed projects on the front page.

Step 3. When you finish a project, change the font to “strike-through” and create a list of the freed-up resources.

Step 4. Flip to the back of the page, allocate the freed-up resources to one of the projects, and move the fully staffed project to the front of the page.

Step 5. Proceed to Step 2.

This is a straightforward process, but it requires great discipline.

Here’s a mantra to repeat daily – I will finish a project before I start the next one.

Image credit — iggyshoot

How I Develop Engineering Leaders

For the past two decades, I’ve actively developed engineering leaders. A good friend asked me how I do it, so I took some time to write it down. Here is the curriculum in the form of How Tos:

For the past two decades, I’ve actively developed engineering leaders. A good friend asked me how I do it, so I took some time to write it down. Here is the curriculum in the form of How Tos:

How to build trust. This is the first thing. Always. Done right, the trust-based informal networks are stronger than the formal organization chart. Done right, the informal networks can protect the company from bad decisions. Done right, the right information flows among the right engineers at the right time so the right work happens in the right way.

How to decide what to do next. This is a broad one. We start with a series of questions: What are we doing now? What’s the problem? How do you know? What should we do more of? What should we do less of? What resources are available? When must we be done?

How to map the current state. We don’t define the idealized future state or the North Star, we start with what’s happening now. We make one-page maps of the territory. We use drawings, flow charts, boxes/arrows, and the fewest words. And we take no action before there’s agreement on how things are. The value of GPS isn’t to define your destination, it’s to establish your location. That’s why we map the current state.

How to build momentum. It’s easy to jump onto a moving steam train, but a stationary one is difficult to get moving. We define the active projects and ask – How might we hitch our wagon to a fast-moving train?

How to start something new. We start small and make a thought-provoking demo. The prototype forces us to think through all the elements, makes things real, and helps others understand the concept. If that doesn’t work, we start smaller.

How to define problems so we can solve them easily. We define problems with blocks and arrows, and limit ourselves to one page. The problem is defined as a region of contact between two things, and we identify it with the color red. That helps us know where the problem is and when it occurs. If there are two problems on a page, we break it up into two pages with one problem. Then we decide to solve the problem before, during, or after it occurs.

How to design products that work better and cost less. We create Pareto charts of the cost of the existing product (cost by subassembly and cost by part) and set a cost reduction goal. We create Pareto charts of the part count of the existing product (part count by subassembly and part count by individual part number) and define a goal for part count reduction. We define test protocols that capture the functionality customers care about. We test the existing product and set performance improvement goals for the new one. We test the new product using the same protocols and show the data in a simple A-B format. We present all this data at formal design reviews.

How to define technology projects. We define how the customer does their work. We then define the evolutionary history of our products and services, and project that history forward. For lines of goodness with trajectories that predict improvement, we run projects to improve them. For lines of goodness with stalled trajectories, we run projects to establish new technologies and jump to the next S-curve. We assess our offerings for completeness and create technologies to fill the gap.

How to file the right patents. We ask these questions: How quickly will the customer notice the new functionality or benefit? Once recognized, will they care? Will the patent protect high-volume / high-margin consumables? There are more questions, but these are the ones we start with. And the patent team is an integral part of the technology reviews and product development process.

How to do the learning. We start with the leader’s existing goals and deliverables and identify the necessary How Tos to get their work done. There are no special projects or extra work.

If you’re interested in learning more about the curriculum or how to enroll, send me an email mike@shipulski.com.

Image credit — Paul VanDerWerf

Improve Focus To Improve Effectiveness

Business is about the effective allocation of resources. Companies win when they do that better than their competitors. Full stop. If you believe that, the question is how to allocate resources effectively. To me, everything starts with a map of the territory – a single-page map of today’s projects, the people you have, and the tools/infrastructure you have. In short, before you can reallocate resources, map how you allocate them now.

Business is about the effective allocation of resources. Companies win when they do that better than their competitors. Full stop. If you believe that, the question is how to allocate resources effectively. To me, everything starts with a map of the territory – a single-page map of today’s projects, the people you have, and the tools/infrastructure you have. In short, before you can reallocate resources, map how you allocate them now.

Let the mapping begin.

The first step is to create a one-page summary (a map) of the resources on hand and the projects they work on (how they are allocated). A simple spreadsheet is the way to go. At the top, running left to right, list the names of all the people. Give each person their column. On the left, running top to bottom, list the active projects, one project per row. For each project, move left to right and ask if the person works on the project. Put an X in their column if they contribute to the project in any way. If they work on the project 2% of their time or more, X marks the spot. You will be reluctant to do this, but the process is more meaningful if you do.

No fancy formats, no extra text, no headings, no footers, just columns of people against rows of projects. And it MUST fit one page. MUST. Reduce the font size and the margins to fit it on one page. And if that doesn’t work, set the print area and choose the setting that scales the print area to fit on one page. Put it on 11 by 17 paper if you must, but you must put it on one page. You’ll have to squint to read the font when you do it right.

When you look at the one-page printout, the first thing you will notice is that you have too many rows because you have too many projects. (And, yes, you should list the quiet projects no one knows about.) The second thing you will notice is that everyone has too many Xs because they work on too many projects. The third thing is some people have far more Xs than everyone else’s too many Xs. All the project managers want them on the projects because they are good at getting projects done.

Let the culling begin.

It’s time to stop. The best way to stop is to set a maximum time threshold to deliver the first dollar of revenue. Any project that cannot deliver revenue sooner than the threshold should stop. The threshold method is crude, fast, and effective. It’s a great way to do the first pass culling. For those projects that are difficult to stop due to political factors, don’t stop them but, rather, strongly pause them. Then, use the reallocation process (described later) to move resources to better projects and let the politically charged projects die a slow death. Good process beats bad projects.

Strike the cancelled projects from the record, eliminate their rows, and reprint the one-page map. If you have the right number of projects and they’re fully staffed (this is unlikely), execute the projects that made the cut. If you have too few projects, the next step is to come up with a set of new projects that deliver revenue sooner than the culled projects. If you still have too many projects (too many people with too many Xs), it’s time to thin the herd again. Sort the projects by the revenue they will generate over the threshold period plus three years. The best projects will bubble to the top, and the bad ones will sink to the bottom.

Let the reallocating begin.

Now, delete all the Xs from the spreadsheet so none of the projects are staffed and no one has a project. Start with the top row (your best project), move left to right, and place an X in the columns until the project is fully staffed. Allocate the resources to your best project and get after it right now. Because your best project was understaffed, incremental will flow to the project. This will increase the probability you will hit the launch date or even pull it in.

Next, move down one row to your second-best project and repeat the process. Add Xs left to right until the project is fully staffed. But this time there’s a constraint – each column can contain only one X. Because the people are now fully allocated to and actively working on your best project, they cannot work on the second-best project. With all the Xs in place and your second-best project fully staffed, work the project hard with the reallocated resources. Pull in the timeline if you can.

Repeat the process project by project until you can no longer fully staff a project. And here’s where the game gets interesting. Don’t work a project you cannot staff fully. There. I said it. With new product development projects, there is no partial credit. They’re either 100% done or 0% done. A project that’s 80% done delivers 0% of the revenue. But it’s worse than that. Making “progress” on a project that won’t launch because it’s understaffed consumes functional support resources and will slow down your most important projects. Don’t do that. Don’t run the project. Just don’t. You’re better off paying the people to stay home so they don’t consume functional resources needed by the more important projects.

Instead of paying the people to stay home, try to add them to the active projects so you can launch those sooner. In theory, those projects are fully staffed, but old behaviors die hard, and you probably didn’t fully staff the most important projects. For the people who still don’t have a project (they cannot speed up the projects), train them on the skills/tools they’ll need for the next round of projects. This will help you do the next projects better and faster. Or, they could start on more forward-looking projects that don’t consume resources needed by the more urgent projects.

The process to allocate people to the most important projects is the same for resources like infrastructure for reliability testing or product validation. With the same fully-staff-the-project approach, allocate the infrastructure resources to the most important projects. Once there is no more infrastructure capacity, don’t run an under-resourced project. If you run the lesser project, it will consume those precious infrastructure resources and slow down your most important projects.

You likely won’t be able to staff projects such that each person works on a single project. The concept is more directional than literal. Working on three projects is better than working on four, and two is better than three.

I did not describe how to estimate the project revenues, how to create new projects that deliver more revenue sooner, or how to create the right mix of projects – short, medium, and long. But in a first-things-first way, I suggest you start with a singular focus – reallocate resources to your best projects (and, likely, fewer of them), so those projects effectively deliver revenue your company needs.

I think more focus will bring you more effectiveness.

Image credit — Charlie Wales

How To Make Progress

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improving the right thing to make progress. If the problem invalidates the business model, stop what you’re doing and solve it right away because you don’t have a business if you don’t solve it. Any other activity isn’t progress, it’s dilution. Say no to everything else and solve it. This is how rapid progress is made. If the customer won’t buy the product if the problem isn’t solved, solve it. Don’t argue about priorities, don’t use shared resources, don’t try to be efficient. Be effective. Do one thing. Solve it. This type of discipline reduces time to market. No surprises here.

Avoiding improvement of the wrong thing to make progress. For lesser problems, declare them nuisances and permit yourself to solve them later. Nuisances don’t have to be solved immediately (if at all) so you can double down on the most important problems (speed, speed, speed). Demoting problems to nuisances is probably the most effective way to accelerate progress. Deciding what you won’t do frees up resources and emotional bandwidth to make rapid progress on things that matter.

Work the critical path to make progress. Know what work is on the critical path and what is not. For work on the critical path, add resources. Pull resources from non-critical path work and add them to the critical path until adding more slows things down.

Eliminate waiting to make progress. There can be no progress while you wait. Wait for a tool, no progress. Wait for a part from a supplier, no progress. Wait for raw material, no progress. Wait for a shared resource, no progress. Buy the right tools and keep them at the workstations to make progress. Pay the supplier for priority service levels to make progress. Buy inventory of raw materials to make progress. Ensure shared resources are wildly underutilized so they’re available to make progress whenever you need to. Think fire stations, fire trucks, and firefighters.

Help the team make progress. As a leader, jump right in and help the team know what progress looks like. Praise the crudeness of their prototypes to help them make them cruder (and faster) next time. Give them permission to make assumptions and use their judgment because that’s where speed comes from. And when you see “activity” call it by name so they can recognize it for themselves, and teach them how to turn their effort into progress.

Be relentless and respectful to make progress. Apply constant pressure, but make it sustainable and fun.

Image credit — Clint Mason

Top Blog Posts of 2024

Here are the top four blog posts from 2024 with a little summary of each.

Here are the top four blog posts from 2024 with a little summary of each.

It’s not the work, it’s the people. By far the most popular post. Here are some important words from the post: hard work, share, struggle, elbow-to-elbow, fear, crew, extra load, friend, through the wringer, smile, sad, care, easier. And I finished with a challenge.

For the most important people, take a minute and write down your shared experiences and what they mean to you. What would it mean to them if you shared your thoughts and feelings? Why not take a minute and find out? Wouldn’t work be more energizing and fun? If you agree, why not do it? What’s in the way? What’s stopping you?

Why not push through the discomfort and take things to the next level?

Projects, Products, People, and Problems. The post was written within the tight context of product development systems, but I think the tight one-liners have broader applicability. Here are a few of may favorites.

- To get more projects done, do fewer of them.

- Stop starting and start finishing.

- People grow when you create the conditions for their growth.

- When in doubt, help people.

- Trust is all-powerful.

- Whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Pro Tips for New Product Development Projects. This one was one was narrow and deep. Here are the main themes:

- Effectiveness is more important than efficiency, but we behave otherwise.

- Everyone has too many projects and that’s why they take so long.

- Resources – too highly utilized.

- Novelty – too much of a good thing isn’t wonderful.

I’m thankful! I wrote this for the Thanksgiving holiday. There were four themes: family, health, time, and telling people about your thankfulness. Family – straightforward. Health – appreciating our remaining health because we recognize it flowing away. This one is a little backward, but the Stoics know. And so does Buddha. Time – appreciation of our time, especially when others pull on us. Telling people about our thankfulness – this a great way to multiply the impact of our thankfulness.

Happy New Year and thanks for reading, Mike

Image credit — Anna Sofia Guerreirinho

Effectiveness Before Efficiency

Efficient – How do we do more projects with fewer people?

Efficient – How do we do more projects with fewer people?

Effective – Let’s choose the right project.

Would you rather do more projects that miss the mark or fewer that excite the customer?

Efficient – How do we finish the project faster?

Effective – Let’s fully staff the project.

Would you rather burn out the project team or deliver on what the customer wants?

Efficient – How do we reduce product cost by 5%?

Effective – Let’s make customers’ lives easier.

Would you rather reduce the cost or delight the customer?

Efficient – How can we go faster?

Effective – Let’s get it right.

Would you rather go fast and break things or get it right for the customer?

Efficient – How many projects can we run in parallel?

Effective – Let’s fully staff the most important projects.

Would you rather get halfway through four projects or complete two?

Efficient – How do we make progress on as many tasks as possible?

Effective – Let’s work on the critical path.

Would you rather work on things that don’t matter or nail the things that do?

Efficient – How can we complete the most tasks?

Effective – Let’s work on the hardest thing first.

Would you rather learn the whole thing won’t work before or after you waste time on the irrelevant?

If there’s a choice between efficiency and effectiveness, I choose effectiveness.

Image credit — Antarctica Bound

Why We Wait

We wait because we don’t have enough information to make a decision.

We wait because we don’t have enough information to make a decision.

We wait until the decision makes itself because no one wants to be wrong.

We wait for permission because of the negative consequences of being wrong.

We wait to use our judgment until we have evidence our judgment is right.

We wait for support resources because they are spread over too many projects.

We wait for a decision to be made because no one is sure who makes it.

We wait to reduce risk.

We wait to reduce costs.

We wait to move at the speed of trust.

We wait because too many people must agree.

We wait because disagreement comes too slowly.

We wait for disagreement because we don’t subscribe to “clear is kind.”

We wait when decisions are unmade.

We wait because there is insufficient courage to stop the bad projects.

We wait to stop things slowly.

We use waiting as a slow no.

We wait to reallocate resources because even bad projects have momentum.

We wait when we dislike the impending outcome.

We wait for the critical path.

We wait out of fear.

Image credit — Sylvia Sassen

Pro Tips for New Product Development Projects

Do the project right or do the right project – which would you choose?

Do the project right or do the right project – which would you choose?

If you improve time to market, the only thing that improves is time to market. How do you feel about that?

Customers pay for things that make their lives easier. Time to market doesn’t do that.

There’s no partial credit with new product development projects. If the product isn’t 100% ready for sale, it’s 0% ready.

If you made 1/8th progress on 8 projects, you made zero progress. But you did consume valuable resources.

If you made 100% progress on one project, you made progress.

When you have too many projects, you get too few done.

If you don’t know how many projects your company has, you have too many.

Would you rather choose the right project and run it inefficiently or choose the wrong project and run it efficiently?

When you choose the wrong project but run it efficiently, that’s called efficient ineffectiveness.

You can save several weeks making sure you choose the right project by starting the project too soon and running the wrong one for two years.

If your projects are slow, it’s likely the support functions are too highly utilized. Add capacity to keep their peak utilization below 85%.

When shared resources are sized appropriately, they’re underutilized most of the time. Think fire station and firefighters – when there’s a fire they respond quickly, and when there’s no fire they improve their skills so they can fight the next one better than the last.

If your projects are slow, check to see if you have resources on the critical path that work part-time. Part-time resources support multiple projects and don’t work full-time on your project. And you can’t control when they work on your project. There’s no place for that on the critical path.

If you’re thinking about using part-time resources on the critical path, don’t.

Know where the novelty is and work that first. And before you can work on the novelty you’ve got to know where it is.

You can have too little novelty, meaning the new product is so much like the old one there’s no need to launch it. Mostly, though, projects have too much novelty.

If you are working on a clean-sheet design, there is no such thing. There are no green-field projects. All projects are brown-field projects. It’s just that some are browner than others.

Novelty generates problems and problems take three times longer to solve than anyone thinks. To reduce the number of problems, declare as many as possible as annoyances. Unlike problems, annoyances don’t have to be solved by the project. Remember, it’s okay to save some work for the next project.

Even though you have a product development process, that process is powered by people. People make it work and people make it not work. If you get one thing right, get the people part right.

Image credit – claudia gabriela marques

How flexible are your processes and how do you know?

What would happen if the factory had to support demand that increased one percent per week? Without incremental investment, how many weeks could they meet the ever-increasing demand? That number is a measure of the system’s flexibility. More weeks, more flexibility. And the element of the manufacturing system that gives out first is the constraint. So, now you know how much demand you can support before there’s a problem and you know what the problem will be. And if you know the lead time to implement the improvement needed to support the increased demand, in a reverse-scheduling way, you know when to implement the improvement so it comes online when you need it.

What would happen if the factory had to support demand that increased one percent per week? Without incremental investment, how many weeks could they meet the ever-increasing demand? That number is a measure of the system’s flexibility. More weeks, more flexibility. And the element of the manufacturing system that gives out first is the constraint. So, now you know how much demand you can support before there’s a problem and you know what the problem will be. And if you know the lead time to implement the improvement needed to support the increased demand, in a reverse-scheduling way, you know when to implement the improvement so it comes online when you need it.

What would happen if the factory had to support demand that increased one percent in a week? How about two percent in a week, five percent, or ten percent? Without incremental investment, what percentage increase could they support in a single week? More percent increase, more flexibility. And the element of the manufacturing system that gives out first is the constraint. So, now you know how much increased demand you can support in a single week and you know the gating item that will block further increases. You know now where to clip the increased demand and push the extra demand into the next week. And you know the investment it would take to support a larger increase in a single week.

These two scenarios can be used to assess and quantify a process of any type. For example, to understand the flexibility of the new product development process, load it (virtually) with more projects to see where it breaks. Make a note of what it would take to increase the system’s flexibility and ask yourself if that’s a good investment. If it is, make that investment. If it isn’t, don’t.

This simple testing method is especially useful when the investment needed to increase flexibility has a long lead time or is expensive. If your testing says the system can support five percent more demand before it breaks and you know that demand will hit the system in ten weeks, I hope the lead time to implement the needed improvement is less than ten weeks. If not, you won’t be able to meet the increased demand. And I hope the money to make the improvement is already budgeted because a budgeting cycle is certainly longer than ten weeks and you can’t buy what you need if the money isn’t in the budget.

The first question to ask yourself is what is the minimum flexibility of the system that will trigger the next investment to improve throughput and increase flexibility? And the follow-on question: What is needed to improve throughput? What is the lead time for that solution? How much will it cost? Is the money budgeted? And do we have the resources (people) that can implement the improvement when it’s time?

When the cost of not meeting demand is high, the value of this testing process is high. When the lead times for the improvements are long, this testing process has a lot of value because it gives you time to put the improvements in place.

Continuous improvement of process utilization is also a continuous reduction of process flexibility. This simple testing approach can help identify when process flexibility is becoming dangerously low and give you the much-needed time to put improvements in place before it’s too late.

Image credit — Tambako The Jaguar

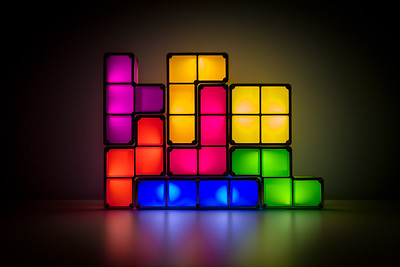

Playing Tetris With Your Project Portfolio

When planning the projects for next year, how do you decide which projects are a go and which are a no? One straightforward way is to say yes to projects when there are resources lined up to get them done and no to all others. Sure, the projects must have a good return on investment but we’re pretty good at that part. But we’re not good at saying no to projects based on real resource constraints – our people and our budgets.

When planning the projects for next year, how do you decide which projects are a go and which are a no? One straightforward way is to say yes to projects when there are resources lined up to get them done and no to all others. Sure, the projects must have a good return on investment but we’re pretty good at that part. But we’re not good at saying no to projects based on real resource constraints – our people and our budgets.

It’s likely your big projects are well-defined and well-staffed. The problem with these projects is usually the project timeline is disrespectful of the work content and the timeline is overly optimistic. If the project timeline is shorter than that of a previously completed project of a similar flavor, with a similar level of novelty and similar resource loading, the timeline is overly optimistic and the project will be late.

Project delays in the big projects block shared resources from moving onto other projects within the appropriate time window which cascades delays into those other projects. And the project resources themselves must stay on the big projects longer than planned (we knew this would happen even before the project started) which blocks the next project from starting on time and generates a second set of delays that rumble through the project portfolio. But the big projects aren’t the worst delay-generating culprits.

The corporate initiatives and infrastructure projects are usually well-staffed with centralized resources but these projects require significant work from the business units and is an incremental demand for them. And the only place the business units can get the resources is to pull them off the (too many) big projects they’ve already committed to. And remember, the timelines for those projects are overly optimistic. The big projects that were already late before the corporate initiatives and infrastructure projects are slathered on top of them are now later.

Then there are small projects that don’t look like they’ll take long to complete, but they do. And though the project plan does not call for support resources (hey, this is a small project you know), support resources are needed. These small projects drain resources from the big projects and the support resources they need. Delay on delay on delay.

Coming out of the planning process, all teams are over-booked with too many projects, too few resources, and timelines that are too short. And then the real fun begins.

Over the course of the year, new projects arise and are started even though there are already too few resources to deliver on the existing projects. Here’s a rule no one follows: If the teams are fully-loaded, new projects cannot start before old ones finish.

It makes less than no sense to start projects when resources are already triple-double booked on existing projects. This behavior has all the downside of starting a project (consumption of resources) with none of the upside (progress). And there’s another significant downside that most don’t see. The inappropriate “starting” of the new project allows the company to tell itself that progress is being made when it isn’t. All that happens is existing projects are further starved for resources and the slow pace of progress is slowed further.

It’s bad form to play Tetris with your project portfolio.

Running too many projects in parallel is not faster. In fact, it’s far slower than matching the projects to the resources on-hand to do them. It’s essential to keep in mind that there is no partial credit for starting a project. There is 100% credit for finishing a project and 0% credit for starting and running a project.

With projects, there are two simple rules. 1) Limit the number of projects by the available resources. 2) Finish a project before starting one.

Image credit – gerlos

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski