Posts Tagged ‘Fear’

520 Wednesdays in a Row

This is a special post for me. It’s a huge milestone. With this post, I have written a new blog post every Wednesday evening for the last ten years. That’s 520 Wednesdays in a row. I haven’t missed a single one and none have been repeats. As I write this, the significance is starting to sink in.

This is a special post for me. It’s a huge milestone. With this post, I have written a new blog post every Wednesday evening for the last ten years. That’s 520 Wednesdays in a row. I haven’t missed a single one and none have been repeats. As I write this, the significance is starting to sink in.

Most of the posts I’ve written at the kitchen table with my earbuds set firmly in my ears and my family going about its business around me. But I’ve written them in the car; I’ve written them in a hospital waiting room; I’ve written them in a diner over lunch while on a three-week motorcycle trip, and I’ve written them at a state park while on vacation. No matter what, I’ve published a post on Wednesday night.

I write to challenge myself. I write to teach myself. I write to provide my own mentorship. I have no one to proof my writing and there are always mistakes of grammar, spelling and word choice. But that doesn’t stop me. No one limits the topics I cover, nor does anyone help me choose a topic. It’s just me and my laptop battling it out. It doesn’t have to be that way, but that’s the way it has been for the last ten years.

I used to read, respond and obsess over comments written by readers, but I started to limit my writing based on them so now my posts are closed to comments. I write more freely now, but I miss the connection that came from the comments.

I used to obsessively track the number of subscribers and Google analytics data. Now I don’t know how many subscribers I have, nor do I know who has visited my website over the last couple of years. Now I just write. But maybe I should check.

When you can write about anything you want, the topics you choose make a fingerprint, or maybe a soul-print. I don’t know what my choices say about me, but that’s the old me.

What’s the grand plan? There isn’t one. What’s next? It’s uncertain.

Thanks for reading.

Mike

image credit — Joey Gannon

If you’re not sure…

If you’re not sure, it likely hasn’t been done before.

If you’re not sure, it likely hasn’t been done before.

If you’re sure it’s been done before, teach someone how to do it.

If you’re not sure, you may not know how people will respond.

If you’re sure how they’ll respond, why bother?

If you’re not sure, you may be onto something.

If you’re sure, it’s re-hash.

If you’re not sure, it deserves your time.

If you’re sure, it deserves to be done poorly.

If you’re not sure, the uncertainty may be a sign of importance.

If you’re sure, it’s important someone else does it.

If you’re not sure, it may be a big learning opportunity.

If you’re sure, take the opportunity to learn something else.

If you’re not sure, your idea may threaten the status quo.

If you’re sure the status quo will like it, commit to something else to threaten the timeline.

If you’re not sure, it will be exciting.

If you’re sure, it will be exciting to grow someone worthy.

If you’re not sure, invest the time to figure out the fundamentals.

If you’re sure, invest in a future leader and teach them the fundamentals.

If you’re not sure, do it anyway.

If you’re sure, do something else.

Image credit – Nik Wallenda

The Difficulty of Commercializing New Concepts

If you have the data that says the market for the new concept is big enough, you waited too long.

If you have the data that says the market for the new concept is big enough, you waited too long.

If you require the data that verifies the market is big enough before pursuing new concepts, you’ll never pursue them.

If you’re afraid to trust the judgement of your best technologists, you’ll never build the traction needed to launch new concepts.

If you will sell the new concept to the same old customers, don’t bother. You already sold them all the important new concepts. The returns have already diminished.

If you must sell the new concept to new customers, it could create a whole new business for you.

If you ask your successful business units to create and commercialize new concepts, they’ll launch what they did last time and declare it a new concept.

If you leave it to your successful business units to decide if it’s right to commercialize a new concept created by someone else, they won’t.

If a new concept is so significant that it will dwarf the most successful business unit, the most successful business unit will scuttle it.

If the new concept is so significant it warrants a whole new business unit, you won’t make the investment because the sales of the yet-to-be-launched concept are yet to be realized.

If you can’t justify the investment to commercialize a new concept because there are no sales of the yet-to-be-launched concept, you don’t understand that sales come only after you launch. But, you’re not alone.

If a new concept makes perfect sense, you would have commercialized it years ago.

If the new concept isn’t ridiculed by the Status Quo, do something else.

If the new concept hasn’t failed three times, it’s not a worthwhile concept.

If you think the new concept will be used as you intend, think again.

If you’re sure a new concept will be a flop, you shouldn’t be. Same goes for the ones you’re sure will be successful.

If you’re afraid to trust your judgement, you aren’t the right person to commercialize new concepts.

And if you’re not willing to put your reputation on the line, let someone else commercialize the new concept.

Image credit – Melissa O’Donohue

As a leader, be truthful and forthcoming.

Have you ever felt like you weren’t getting the truth from your leader? You know – when they say something and you know that’s not what they really think. Or, when they share their truth but you can sense that they’re sharing only part of the truth and withholding the real nugget of the truth? We really have no control over the level of forthcoming of our leaders, but we do have control over how we respond to their incomplete disclosure.

There are times when leaders cannot, by law, disclose things. But, even then, they can make things clear without disclosing what legally cannot be disclosed. For example, they can say: “That’s a good question and it gets to the heart of the situation. But, by law, I cannot answer that question.” They did not answer the question, but they did. They let you know that you understand the situation; they let you know that there is an answer; and the let you know why they cannot share it with you. As the recipient of that non-answer answer, I respect that leader.

There are also times when a leader withholds information or gives a strategically partial response for inappropriate reasons. When a leader withholds information to manipulate or control, that’s inappropriate. It’s also bad leadership. When a leader withholds information from their smartest team members, they lose trust. And when leaders lose trust, the best people are crestfallen and withhold their best work. The thinking goes like this. If my leader doesn’t trust me enough to share the complete set of information with me it’s because they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust and they don’t think highly of me. And if they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust, they don’t understand who I am and what I stand for. And if they don’t understand me and know what I stand for, they’re not worthy of my best work.

As a leader, you must share all you can. And when you can’t, you must tell your team there are things you can’t share and tell them the reasons why. Your team can handle the fact that there are some things you cannot share. But what your team cannot hand is when you withhold information so you can gain the upper hand on them. And your team can tell when you’re withholding with your best interest in mind. Remember, you hired them because they were smart, and their smartness doesn’t go away just because you want to control them.

If your direct reports always tell you they can get it done even when they don’t have the capacity and capability, that’s not the behavior you want. If your direct reports tell you they can’t get it done when they can’t get it done, that’s the behavior you want. But, as a leader, which behavior do you reward? Do you thank the truthful leader for being truthful about the reality of insufficient resources and do you chastise the other leader for telling you what you want to hear? Or, do you tell the truthful leader they’re not a team player because team players get it done and praise the unjustified can-do attitude of the “yes man” leader? As a leader, I suggest you think deeply about this. As a direct report of a leader, I can tell you I’ve been punished for responding in way that was in line with the reality of the resources available to do the work. And I can also tell you that I lost all respect for that leader.

As a leader, you have three types of direct reports. Type I are folks are happy where they are and will do as little as possible to keep it that way. Type II are people that are striving for the next promotion and will tell you whatever you want to hear in order to get the next job. Type III are the non-striving people who will tell you what you need to hear despite the implications to their career. Type I people are good to have on your team. They know what they can do and will tell you when the work is beyond their capability. Type II people are dangerous because they think only of themselves. They will hang you out to dry if they think it will advance their career. And Type III people are priceless.

Type III people care enough to protect you. When you ask them for something that can’t be done, they care enough about you to tell you the truth. It’s not that they don’t want to get it done, they know they cannot. And they’re willing to tell you to your face. Type II people don’t care about you as a leader; they only care about themselves. They say yes when they know the answer is no. And they do it in a way that absolves them of responsibility when the wheels fall off. As a leader, which type do you want on your team? And as a leader, which type do you promote and which do you chastise. And, how do you feel about that?

As a leader, you must be truthful. And when you can’t disclose the full truth, tell people. And when your Type II direct reports give you the answer they know you want to hear, call them on their bullshit. And when your Type III folks give you the answer they know you don’t want to hear, thank them.

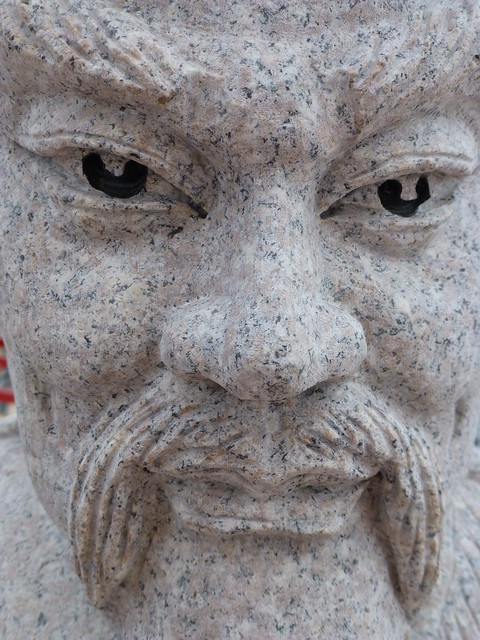

Image credit — Anandajoti Bhikkhu

Innovation Truths

If it’s not different, it can’t be innovation.

If it’s not different, it can’t be innovation.

With innovation, ideas are the easy part. The hard part is creating the engine that delivers novel value to customers.

The first goal of an innovation project is to earn the right to do the second hardest thing. Do the hardest thing first.

Innovation is 50% customer, 50% technology and 75% business model.

If you know how it will turn out, it’s not innovation.

Don’t invest in a functional prototype until customers have placed orders for the sell-able product.

If you don’t know how the customer will benefit from your innovation, you don’t know anything.

If your innovation work doesn’t threaten the status quo, you’re doing it wrong.

Innovation moves at the speed of people.

If you know when you’ll be finished, you’re not doing innovation.

With innovation, the product isn’t your offering. Your offering is the business model.

If you’re focused on best practices, you’re not doing innovation. Innovation is about doing things for the first time.

If you think you know what the customer wants, you don’t.

Doing innovation within a successful company is seven times hard than doing it in a startup.

If you’re certain, it’s not innovation.

With innovation, ideas and prototypes are cheap, but building the commercialization engine is ultra-expensive.

If no one will buy it, do something else.

Technical roadblocks can be solved, but customer/market roadblocks can be insurmountable.

The first thing to do is learn if people will buy your innovation.

With innovation, customers know what they don’t want only after you show them your offering.

With innovation, if you’re not scared to death you’re not trying hard enough.

The biggest deterrent to innovation is success.

Image credit — Sherman Geronimo-Tan

Seeing Things as They Can’t Be

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

Seeing things as they are. The same logic applies when it’s time to improve an existing product or service. The first thing to do is to see the system as it is. But seeing things as they are is difficult. We have a tendency to see things as we want them or to see them in ways that make us look good (or smart). Or, we see them in a way that justifies the improvements we already know we want to make.

To battle our biases and see things as they are, we use tools such as block diagrams to define the system as it is. The most important element of the block diagram is clarity. The first revision will be incorrect, but it must be clear and explicit. It must describe things in a way that creates a singular understanding of the system. The best block diagrams can be interpreted only one way. More strongly, if there’s ambiguity or lack of clarity, the thing has not yet risen to the level of a block diagram.

The block diagram evolves as the team converges on a single understanding of things as they are. And with a diagram of things as they are, a solution is readily defined and validated. If when tested the proposed solution makes the problem go away, it’s inferred that the team sees things as they are and the solution takes advantage of that understanding to make the problem go away.

Seeing things as they may be. Even whey the solution fixes the problem, the team really doesn’t know if they see things as they are. Really, all they know is they see things as they may be. Sure, the solution makes the problem go away, but it’s impossible to really know if the solution captures the physics of failure. When the system is large and has a lot of moving parts, the team cannot see things as they are, rather, they can only see the system as it may be. This is especially true if the system involves people, as people behave differently based on how they feel and what happened to them yesterday.

There’s inherent uncertainty when working with larger systems and systems that involve people. It’s not insurmountable, but you’ve got to acknowledge that your understanding of the system is less than perfect. If your company is used to solving small problems within small systems, there will be little tolerance for the inherent uncertainty and associated unpredictability (in time) of a solution. To help your company make the transition, replace the language of “seeing things as they are” with “seeing things as they may be.” The same diagnostic process applies, but since the understanding of the system is incomplete or wrong, the proposed solutions cannot not be pre-judged as “this will work” and “that won’t work.” You’ve got to be open to all potential solutions that don’t contradict the system as it may be. And you’ve got to be tolerant of the inherent unpredictability of the effort as a whole.

Seeing things as they could be. To create something that doesn’t yet exist, something does things like never before, something altogether new, you’ve got to stand on top of your understanding of the system and jump off. Whether you see things as they are or as they may be, the new system will be different. It’s not about diagnosing the existing system; it’s about imagining the system as it could be. And there’s a paradox here. The better you understand the existing system, the more difficulty you’ll have imagining the new one. And, the more success the company has had with the system as it is, the more resistance you’ll feel when you try to make the system something it could be.

Seeing things as they could be takes courage – courage to obsolete your best work and courage to divest from success. The first one must be overcome first. Your body creates stress around the notion of making yourself look bad. If you can create something altogether better, why didn’t you do it last time? There’s a hit to the ego around making your best work look like it’s not all that good. But once you get over all that, you’ve earned the right to go to battle with your organization who is afraid to move away from the recipe responsible for all the profits generated over the last decade.

But don’t look at those fears as bad. Rather, look at them as indicators you’re working on something that could make a real difference. Your ego recognizes you’re working on something better and it sends fear into your veins. The organization recognizes you’re working on something that threatens the status quo and it does what it can to make you stop. You’re onto something. Keep going.

Seeing things as they can’t be. This is rarified air. In this domain you must violate first principles. In this domain you’ve got to run experiments that everyone thinks are unreasonable, if not ill-informed. You must do the opposite. If your product is fast, your prototype must be the slowest. If the existing one is the heaviest, you must make the lightest. If your reputation is based on the highest functioning products, the new offering must do far less. If your offering requires trained operators, the new one must prevent operator involvement.

If your most seasoned Principal Engineer thinks it’s a good idea, you’re doing it wrong. You’ve got to propose an idea that makes the most experienced people throw something at you. You’ve got to suggest something so crazy they start foaming at the mouth. Your concepts must rip out their fillings. Where “seeing things as they could be” creates some organizational stress, “seeing things as they can’t be” creates earthquakes. If you’re not prepared to be fired, this is not the domain for you.

All four of these domains are valuable and have merit. And we need them all. If there’s one message it’s be clear which domain you’re working in. And if there’s a second message it’s explain to company leadership which domain you’re working in and set expectations on the level of uncertainty and unpredictability of that domain.

Image credit – David Blackwell.

The Trust Network II

I stand by my statement that trust is the most important element in business (see The Trust Network.)

I stand by my statement that trust is the most important element in business (see The Trust Network.)

The Trust Network are the group of people who get the work done. They don’t do the work to get promoted, they just do the work because they like doing the work. They don’t take others’ credit (they’re not striving,) they just do the work. And they help each other do the work because, well, it’s the right thing to do.

Sometimes, they use their judgement to protect the company from bad ideas. But to be clear, they don’t protect the Status Quo. They use their good judgement to decide if a new idea has merit, and if it doesn’t, they try to shape it. And if they can’t shape it, they block it. Their judgement is good because their mutual trust allows them to talk openly and honestly and listen to each other. And through the process, they come to a decision and act on it.

But there’s another side to the Trust Network. They also bring new ideas to the company.

Trying new things is scary, but the Trust Network makes it safe. When someone has a good idea, the Network positively reinforces the goodness of the idea and recommends a small experiment. And when one installment of positivity doesn’t carry the day, the Trust Network comes together to create the additional positivity need to grow the idea into an experiment.

To make it safe, the Trust Network knows to keep the experiment small. If the small experiment doesn’t go as planned, they know there will be no negative consequences. And if the experiment’s results do attract attention, they dismiss the negativity of failure and talk about the positivity of learning. And if there is no money to run the experiment, they scare it up. They don’t stop until the experiment is completed.

But the real power of the Trust Network shows its hand after the successful experiment. The toughest part of innovation is the “now what” part, where successful experiments go to die. Since no one thought through what must happen to convert the successful experiment to a successful product, the follow-on actions are undefined and unbudgeted and the validated idea dies. But the Trust Network knows all this, so they help the experimenter define the “then what” activities before the experiment is run. That way, the resources are ready and waiting when the experiment is a success. The follow-on activities happen as planned.

The Trust Network always reminds each other that doing new things is difficult and that it’s okay that the outcome of the experiment is unknown. In fact, they go further and tell each other that the outcome of the experiment is unknowable. Regardless of the outcome of the experiment, the Trust Network is there for each other.

To start a Trust Network, find someone you trust and trust them. Support their new ideas, support their experiments and support the follow-on actions. If they’re afraid, tell them to be afraid and run the experiment. If they don’t have the resources to run the experiment, find the resources for them. And if they’re afraid they won’t get credit for all the success, tell them to trust you.

And to grow your Trust Network, find someone else you trust and trust them. And, repeat.

Image credit — Rolf Dietrich Brecher

Business is about feelings and emotions.

If you use your sane-and-rational lenses and the situation doesn’t make sense, that’s because the situation is not governed by sanity and rationality. Yet, even though there’s a mismatch between the system’s behavior and sane-and-rational, we still try to understand the system through the cloudy lenses of sanity and rationality.

If you use your sane-and-rational lenses and the situation doesn’t make sense, that’s because the situation is not governed by sanity and rationality. Yet, even though there’s a mismatch between the system’s behavior and sane-and-rational, we still try to understand the system through the cloudy lenses of sanity and rationality.

Computer programs are sane and rational; Algorithms are sane and rational; Machines are sane and rational. Fixed inputs yield predicted outputs; If this, then that; Repeat the experiment and the results are repeated. In the cold domain of machines, computer programs and algorithms you may not like the output, but you’re not surprised by it.

But businesses are not run by computer programs, algorithms and machines. Businesses are run by people. And that’s why things aren’t always sane and rational in business.

Where computer programs blindly follow logic that’s coded into them, people follow their emotions. Where algorithms don’t decide what to do based on their emotional state, people do. And where machines aren’t afraid to try something new, people are.

When something doesn’t make sense to you, it’s because your assumptions about the underlying principles are wrong. If you see things that violate logic, it’s because logic isn’t the guiding principle. And if logic isn’t the guiding principle, the only other things that could be driving the irrationality are feelings and emotions. But if you think the solution is to make the irrational system behave rationally, be prepared to be perplexed and frustrated.

The underpinnings of management and leadership are thoughts, feelings and emotions. And, thoughts are governed by feelings and emotions. In that way, the currency of management and leadership is feelings and emotions.

If your first inclination is to figure out a situation using logic, don’t. Logic is for computers, and even that’s changing with deep learning. Business is about people. When in doubt, assess the feelings and emotions of the people involved. And once you understand their thoughts and feelings, you’ll know what to do.

Business isn’t about algorithms. Business is about people. And people respond based on their emotional state. If you want to be a good manager, focus on people’s feelings and emotions. And if you want to be a good leader, do the same.

Image credit: Guiseppe Milo

On Gumption

Doing new work takes gumption. But there are two problems with gumption. One, you’ve got to create it from within. Two, it takes a lot of energy to generate the gumption and to do that you’ve got to be physically fit and mentally grounded. Here are some words that may help.

Doing new work takes gumption. But there are two problems with gumption. One, you’ve got to create it from within. Two, it takes a lot of energy to generate the gumption and to do that you’ve got to be physically fit and mentally grounded. Here are some words that may help.

Move from self-judging to self-loving. It makes a difference.

It’s never enough until you decide it’s enough. And when you do, you can be more beholden to yourself.

You already have what you’re looking for. Look inside.

Taking care of yourself isn’t selfish, it’s self-ful.

When in doubt, go outside.

You can’t believe in yourself without your consent.

Your well-being is your responsibility. And it’s time to be responsible.

When you move your body, your mind smiles.

With selfish, you take care of yourself at another’s expense. With self-ful, you take care of yourself because you’re full of self-love.

When in doubt, feel the doubt and do it anyway.

If you’re not taking care of yourself, understand what you’re putting in the way and then don’t do that anymore.

You can’t help others if you don’t take care of yourself.

If you struggle with taking care of yourself, pretend you’re someone else and do it for them.

Image credit — Ramón Portellano

You can’t innovate when…

Your company believes everything should always go as planned.

You still have to do your regular job.

The project’s completion date is disrespectful of the work content.

Your company doesn’t recognize the difference between complex and complicated.

The team is not given the tools, training, time and a teacher.

You’re asked to generate 500 ideas but you’re afraid no one will do anything with them.

You’re afraid to make a mistake.

You’re afraid you’ll be judged negatively.

You’re afraid to share unpleasant facts.

You’re afraid the status quo will be allowed to squash the new ideas, again.

You’re afraid the company’s proven recipe for success will stifle new thinking.

You’re afraid the project team will be staffed with a patchwork of part time resources.

You’re afraid you’ll have to compete for funding against the existing business units.

You’re afraid to build a functional prototype because the value proposition is poorly defined.

Project decisions are consensus-based.

Your company has been super profitable for a long time.

The project team does not believe in the project.

Image credit Vera & Gene-Christophe

Your response is your responsibility.

If you don’t want to go to work in the morning, there’s a reason. If’ you/re angry with how things go, there’s a reason. And if you you’re sad because of the way that people treat you, there’s a reason. But the reason has nothing to do with your work, how things are going or how people treat you. The reason has everything to do with your ego.

If you don’t want to go to work in the morning, there’s a reason. If’ you/re angry with how things go, there’s a reason. And if you you’re sad because of the way that people treat you, there’s a reason. But the reason has nothing to do with your work, how things are going or how people treat you. The reason has everything to do with your ego.

And your ego has everything to do with what you think of yourself and the identity you attach to yourself. If you don’t want to go to work, it’s because you don’t like what your work says about you or your image of your self. If you are angry with how things go, it’s because how things go says something about you that you don’t like. And if you’re sad about how people treat you, it’s because you think they may be right and you don’t like what that says about you.

The work is not responsible for your dislike of it. How things go is not responsible for your anger. And people that treat you badly are not responsible for your sadness. Your dislike is your responsibility, your anger is your responsibility and your sadness is your responsibility. And that’s because your response is your responsibility.

Don’t blame the work. Instead, look inside to understand how the work cuts against the grain of who you think you are. Don’t blame the things for going as they go. Instead, look inside to understand why those things don’t fit with your self-image. Don’t blame the people for how they treat you. Instead, look inside to understand why you think they may be right.

It’s easy to look outside and assign blame for your response. It’s the work’s fault, it’s the things’ fault, and it’s the people’s fault. But when you take responsibility for your response, when you own it, work gets better, things go better and people treat you better. Put simply, you take away their power to control how you feel and things get better.

And if work doesn’t get better, things don’t go better and people don’t treat you better, not to worry. Their responses are their responsibility.

Image credit Mrs. Gemstone

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski