Archive for the ‘Top Line Growth’ Category

Three Important Choices for New Product Development Projects

Choose the right project. When you say yes to a new project, all the focus is on the incremental revenue the project will generate and none of the focus is on unrealized incremental revenue from the projects you said no to. Next time there’s a proposal to start a new project, ask the team to describe the two or three most compelling projects that they are asking the company to say no to. Grounding the go/no-go decision within the context of the most compelling projects will help you avoid the real backbreaker where you consume all your product development resources on something that scratches the wrong itch while you prevent those resources from creating something magical.

Choose the right project. When you say yes to a new project, all the focus is on the incremental revenue the project will generate and none of the focus is on unrealized incremental revenue from the projects you said no to. Next time there’s a proposal to start a new project, ask the team to describe the two or three most compelling projects that they are asking the company to say no to. Grounding the go/no-go decision within the context of the most compelling projects will help you avoid the real backbreaker where you consume all your product development resources on something that scratches the wrong itch while you prevent those resources from creating something magical.

Choose what to improve. Give your customers more of what you gave them last time unless what you gave them last time is good enough. Once goodness is good enough, giving customers more is bad business because your costs increase but their willingness to pay does not. Once your offering meets the customers’ needs in one area, lock it down and improve a different area.

Choose how to staff the projects. There is a strong temptation to run many projects in parallel. It’s almost like our objective is to maximize the number of active projects at the expense of completing them. Here’s the thing about projects – there is no partial credit for partially completed projects. Eight active projects that are eight (or eighty) percent complete generate zero revenue and have zero commercial value. For your most important project, staff it fully. Add resources until adding more resources would slow the project. Then, for your next most important project, repeat the process with your remaining resources. And once a project is completed, add those resources to the pool and start another project. This approach is especially powerful because it prioritizes finishing projects over starting them.

“Three Cows” by Sunfox is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Three Scenarios for Scaling Up the Work

Breaking up work into small chunks can be a good way to get things started. Because the scope of each chunk is small, the cost of each chunk is small making it easier to get approval to do the work. The chunk approach also reduces anxiety around the work because if nothing comes from the chunk, it’s not a big deal because the cost of the work is so low. It’s a good way to get started, and it’s a good way to do a series of small chunks that build on each other. But what happens when the chunks are successful and it’s time to scale up the investment by a factor of several hundred thousand or a million?

Breaking up work into small chunks can be a good way to get things started. Because the scope of each chunk is small, the cost of each chunk is small making it easier to get approval to do the work. The chunk approach also reduces anxiety around the work because if nothing comes from the chunk, it’s not a big deal because the cost of the work is so low. It’s a good way to get started, and it’s a good way to do a series of small chunks that build on each other. But what happens when the chunks are successful and it’s time to scale up the investment by a factor of several hundred thousand or a million?

The scaling scenario. When the early work (the chunks) was defined an agreement in principle was created that said the larger investment would be made in a timely way if the small chunks demonstrated the viability of a whole new offering for your customers. The result of this scenario is a large investment is allocated quickly, resources flow quickly, and the scaling work begins soon after the last chunk is finished. This is the least likely scenario.

The more chunks scenario. When the chunks were defined, everyone was excited that the novel work had actually started and there was no real thought about the resources required to scale it into something meaningful and material. Since the resources needed to scale were not budgeted, the only option to keep things going is to break up the work into another series of small chunks. Though the organization sees this as progress, it’s not. The only thing that can deliver the payout the organization needs is to scale up the work. The follow-on chunks distract the company and let it think there is progress, when, really, there is only delayed scaling.

The scale next year scenario. When the chunks were defined, no one thought about scaling so there was no money in the budget to scale. A plan and cost estimate are created for the scaling work and the package waits to be assessed as part of the annual planning process. And as the waiting happens, the people that did the early work (the chunks) move on to other projects and are not available to do the scaling work even if the work gets funded next year. And because the work is new it requires new infrastructure, new resources, new teams, new thinking, and maybe a new company. All this newness makes the price tag significant and it may require more than one annual planning cycle to justify the expense and start the work.

Scaling a new invention into a full-sized business is difficult and expensive, but if you’re looking to create radical growth, scaling is the easiest and least expensive way to go.

“100 Dollar Bills” by Philip Taylor PT is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

The first step is to understand the system as it is.

If there’s a recurring problem, take the time to make sure the system hasn’t changed since last time and make sure the context and environment are still the same. If everything is the same, and there are no people involved in the system, it’s a problem that resides in the clear domain. Here’s a link from Dave Snowden who talks about the various domains. In this video, Dave calls this domain the “simple” domain. Solve it like you did last time.

If there’s a recurring problem, take the time to make sure the system hasn’t changed since last time and make sure the context and environment are still the same. If everything is the same, and there are no people involved in the system, it’s a problem that resides in the clear domain. Here’s a link from Dave Snowden who talks about the various domains. In this video, Dave calls this domain the “simple” domain. Solve it like you did last time.

If there’s a new problem, take the time to understand the elements of the system that surround the problem. Define the elements and define how they interact, and define how they set the context and constraints for the problem. And then, define the problem itself. Define when it happens, what happens just before, and what happens after. If there are no people involved, if the solution is not immediately evident, if it’s a purely mechanical, electromechanical, chemical, thermal, software, or hardware, it’s a problem in the complicated domain (see Dave’s video above) and you’ll be able to solve it with the right experts and enough time.

If you want to know the next evolution of the system, how it will develop and evolve, the situation is more speculative and there’s no singular answer. Still, the first step is the same – take the time to understand the elements of the system and how they interact. Then, look back in time and learn the previous embodiments of the system and define its trajectory – how it evolved into its current state. If there has been consistent improvement along a singular line of goodness, it’s likely the system will want to continue to evolve in that direction. If the improvement has flattened, it’s likely the system will try to evolve along a different line of evolution.

I won’t go into the specifics of lines of evolution of technological systems, as it’s a big topic. But if you want to know more, here’s a nice description of evolution along the line of adaptability by my teacher, Victor Fey – The best products know how to adapt.

If there are people involved with the system, it’s a complex system (see Dave’s video). (There are complex systems that don’t involve people, but I find this a good way to talk about complex systems.) The first step is to define the system as it is, but because the interactions among the elements are not predictable, your only hope is to probe, sense, and respond by doing more of what works and less of what doesn’t. Thanks to Dave Snowden for that language.

The first step is always to understand the system as it is.

“Space – Antennae Galaxies” by Trodel is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

When You Don’t Know What To Do…

When you don’t know what to do, what do you do? This is a difficult question.

When you don’t know what to do, what do you do? This is a difficult question.

Here are some thoughts that may help you figure out what to do when you really don’t know.

Don’t confuse activity with progress.

Gather your two best friends, go off-site, and define the system as it is.

Don’t ask everyone what they think because the Collective’s thoughts will be diffuse, bland, and tired.

Get outside.

Draw a picture of how things work today.

Get a good meal.

Make a graph of goodness over time. If it’s still increasing, do more of what you did last time. If it’s flat, do something else.

Get some exercise.

Don’t judge yourself negatively. This is difficult work.

Get some sleep.

Help someone with their problem. The distraction will keep you out of the way as your mind works on it for you.

Spend time with friends.

Try a new idea at the smallest scale. It will likely lead to a better one. Repeat.

Use your best judgment.

Image credit – Andrew Gustar

Testing is an important part of designing.

When you design something, you create a solution to a collection of problems. But it goes far beyond creating the solution. You also must create objective evidence that demonstrates that the solution does, in fact, solve the problems. And the reason to generate this evidence is to help the organization believe that the solution solves the problem, which is an additional requirement that comes with designing something. Without this belief, the organization won’t go out to the customer base and convince them that the solution will solve their problems. If the sales team doesn’t believe, the customers won’t believe.

When you design something, you create a solution to a collection of problems. But it goes far beyond creating the solution. You also must create objective evidence that demonstrates that the solution does, in fact, solve the problems. And the reason to generate this evidence is to help the organization believe that the solution solves the problem, which is an additional requirement that comes with designing something. Without this belief, the organization won’t go out to the customer base and convince them that the solution will solve their problems. If the sales team doesn’t believe, the customers won’t believe.

In school, we are taught to create the solution, and that’s it. Here are the drawings, here are the materials to make it, here is the process documentation to build it, and my work here is done. But that’s not enough.

Before designing the solution, you’ve got to design the tests that create objective evidence that the solution actually works, that it provides the right goodness and it solves the right problems. This is an easy thing to say, but for a number of reasons, it’s difficult to do. To start, before you can design the right tests, you’ve got to decide on the right problems and the right goodness. And if there’s disagreement and the wrong tests are defined, the design community will work in the wrong areas to generate the wrong value. Yes, there will be objective evidence, and, yes, the evidence will create a belief within the organization that problems are solved and goodness is achieved. But when the sales team takes it to the customer, the value proposition won’t resonate and it won’t sell.

Some questions to ask about testing. When you create improvements to an existing product, what is the family of tests you use to characterize the incremental goodness? And a tougher question: When you develop a new offering that provides new lines of goodness and solves new problems, how do you define the right tests? And a tougher question: When there’s disagreement about which tests are the most important, how do you converge on the right tests?

Image credit — rjacklin1975

Stop reusing old ideas and start solving new problems.

Creating new ideas is easy. Sit down, quiet your mind, and create a list of five new ideas. There. You’ve done it. Five new ideas. It didn’t take you a long time to create them. But ideas are cheap.

Creating new ideas is easy. Sit down, quiet your mind, and create a list of five new ideas. There. You’ve done it. Five new ideas. It didn’t take you a long time to create them. But ideas are cheap.

Converting ideas into sellable products and selling them is difficult and expensive. A customer wants to buy the new product when the underlying idea that powers the new product solves an important problem for them. In that way, ideas whose solutions don’t solve important problems aren’t good ideas. And in order to convert a good idea into a winning product, dirt, rocks, and sticks (natural resources) must be converted into parts and those parts must be assembled into products. That is expensive and time-consuming and requires a factory, tools, and people that know how to make things. And then the people that know how to sell things must apply their trade. This, too, adds to the difficulty and expense of converting ideas into winning products.

The only thing more expensive than converting new ideas into winning products is reusing your tired, old ideas until your offerings run out of sizzle. While you extend and defend, your competitors convert new ideas into new value propositions that bring shame to your offering and your brand. (To be clear, most extend-and-defend programs are actually defend-and-defend programs.) And while you reuse/leverage your long-in-the-tooth ideas, start-ups create whole new technologies from scratch (new ideas on a grand scale) and pull the rug out from under you. The trouble is that the ultra-high cost of extend-and-defend is invisible in the short term. In fact, when coupled with reuse, it’s highly profitable in the moment. It takes years for the wheels to fall off the extend-and-defend bus, but make no mistake, the wheels fall off.

When you find the urge to create a laundry list of new ideas, don’t. Instead, solve new problems for your customers. And when you feel the immense pressure to extend and defend, don’t. Instead, solve new problems for your customers.

And when all that gets old, repeat as needed.

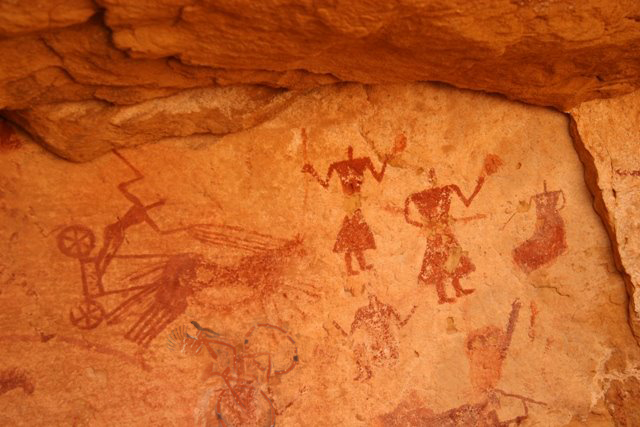

“Cave paintings” by allspice1 is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

What do you like to do?

I like to help people turn complex situations into several important learning objectives.

I like to help people turn complex situations into several important learning objectives.

I like to help people turn important learning objectives into tight project plans.

I like to help people distill project plans into a single-page spreadsheet of who does what and when.

I like to help people start with problem definition.

I like to help people stick with problem definition until the problems solve themselves.

I like to help people structure tight project plans based on resource constraints.

I like to help people create objective measures of success to monitor the projects as they go.

I like to help people believe they can do the almost impossible.

I like to help people stand three inches taller after they pull off the unimaginable.

I like to help people stop good projects so they can start amazing ones.

If you want to do more of what you like and less of what you don’t, stop a bad project to start a good one.

So, what do you like to do?

Image credit — merec0

Three Things for the New Year

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Some things will be the same and some will be different. The trouble is that we won’t know which is which until we do. We can speculate on how it will be different, but the Universe doesn’t care about our speculation. Sure, it can be helpful to think about how things may go, but as long as we hold on to the may-ness of our speculations. And we don’t know when we’ll know. We’ll know when we know, but no sooner. Even when the Operating Plan declares the hardest of hard dates, the Universe sets the learning schedule on its own terms, and it doesn’t care about our arbitrary timelines.

What to do?

Step 1. Try three new things. Choose things that are interesting and try them. Try to try them in parallel as they may interact and inform each other. Before you start, define what success looks like and what you’ll do if they’re successful and if they’re not. Defining the follow-on actions will help you keep the scope small. For things that work out, you’ll struggle to allocate resources for the next stages, so start small. And if things don’t work out, you’ll want to say that the projects consumed little resources and learned a lot. Keep things small. And if that doesn’t work, keep them smaller.

Step 2. Rinse and repeat.

I wish you a happy and safe New Year. And thanks for reading.

Mike

“three” by Travelways.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The Two Sides of the Story

When you tell the truth and someone reacts negatively, their negativity is a surrogate for significance.

When you tell the truth and someone reacts negatively, their negativity is a surrogate for significance.

When you withhold the truth because someone will react negatively, you do everyone a disservice.

When you know what to do, let someone else do it.

When you’re absolutely sure what to do, maybe you’ve been doing it too long.

When you’re in a situation of complete uncertainty, try something. There’s no other way.

When you’re told it’s a bad idea, it’s probably a good one, but for a whole different reason.

When you’re told it’s a good idea, it’s time to come up with a less conventional idea.

When you’re afraid to speak up, your fear is a surrogate for importance.

When you’re afraid to speak up and you don’t, you do your company a disservice.

When you speak up and are met with laughter, congratulations, your idea is novel.

When you get angry, that says nothing about the thing you’re angry about and everything about you.

When someone makes you angry, that someone is always you.

When you’re afraid, be afraid and do it anyway.

When you’re not afraid, try harder.

When you’re understood the first time you bring up a new idea, it’s not new enough.

When you’re misunderstood, you could be onto something. Double down.

When you’re comfortable, stop what you’re doing and do something that makes you uncomfortable.

It’s time to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.

“mirror-image pickup” by jasoneppink is licensed under CC BY 2.0

How To Be Novel

By definition, the approach that made you successful will become less successful over time and, eventually, will run out of gas. This fundamental is not about you or your approach, rather it’s about the nature of competition and evolution. There’s an energy that causes everything to change, grow and improve and your success attracts that energy. The environment changes, the people change, the law changes and companies come into existence that solve problems in better and more efficient ways. Left unchanged, every successful business endeavor (even yours) has a half-life.

By definition, the approach that made you successful will become less successful over time and, eventually, will run out of gas. This fundamental is not about you or your approach, rather it’s about the nature of competition and evolution. There’s an energy that causes everything to change, grow and improve and your success attracts that energy. The environment changes, the people change, the law changes and companies come into existence that solve problems in better and more efficient ways. Left unchanged, every successful business endeavor (even yours) has a half-life.

If you want to extend the life of your business endeavor, you’ve got to be novel.

By definition, if you want to grow, you’ve got to raise your game. You’ve got to do something different. You can’t change everything, because that’s inefficient and takes too long. So, you’ve got to figure out what you can reuse and what you’ve got to reinvent.

If you want to grow, you’ve got to be novel.

Being novel is necessary, but expensive. And risky. And scary. And that’s why you want to add just a pinch of novelty and reuse the rest. And that’s why you want to try new things in the smallest way possible. And that’s why you want to try things in a time-limited way. And that’s why you want to define what success looks like before you test your novelty.

Some questions and answers about being novel:

Is it easy to be novel? No. It’s scary as hell and takes great emotional strength.

Can anyone be novel? Yes. But you need a good reason or you’ll do what you did last time.

How can I tell if I’m being novel? If you’re not scared, you’re not being novel. If you know how it will turn out, you’re not being novel. If everyone agrees with you, you’re not being novel.

How do I know if I’m being novel in the right way? You cannot. Because it’s novel, it hasn’t been done before, and because it hasn’t been done before there’s no way to predict how it will go.

So, you’re saying I can’t predict the outcome of being novel? Yes.

If I can’t predict the outcome of being novel, why should I even try it? Because if you don’t, your business will go away.

Okay. That last one got my attention. So, how do I go about being novel? It depends.

That’s not a satisfying answer. Can you do better than that? Well, we could meet and talk for an hour. We’d start with understanding your situation as it is, how this current situation came to be, and talk through the constraints you see. Then, we’d talk about why you think things must change. I’d then go away for a couple of days and think about things. We’d then get back together and I’d share my perspective on how I see your situation. Because I’m not a subject matter expert in your field, I would not give you answers, but, rather, I’d share my perspective that you could use to inform your choice on how to be novel.

“Giraffe trying to catch a twig with her tongue” by Tambako the Jaguar is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

If you want to understand innovation, understand novelty.

If you want to get innovation right, focus on novelty.

If you want to get innovation right, focus on novelty.

Novelty is the difference between how things are today and how they might be tomorrow. And that comparison calibrates tomorrow’s idea within the context of how things are today. And that makes all the difference. When you can define how something is novel, you have an objective measure of things.

How is it different than what you did last time? If you don’t know, either you don’t know what you did last time or you don’t know the grounding principle of your new idea. Usually, it’s a little of the former and a whole lot of the latter. And if you don’t know how it’s different, you can’t learn how potential customers will react to the novelty. In fact, if you don’t know how it’s different, you can’t even decide who are the right potential customers.

A new idea can be novel in unique ways to different customer segments and it can be novel in opposite ways to intermediaries or other partners in the business model. A customer can see the novelty as something that will make them more profitable and an intermediary can see that same novelty as something that will reduce their influence with the customer and lead to their irrelevance. And, they’ll both be right.

Novelty is in the eye of the beholder, so you better look at it from their perspective.

Like with hot sauce, novelty comes in a range of flavors and heat levels. Some novelty adds a gentle smokey flavor to your favorite meal and makes you smile while the ghost pepper variety singes your palate and causes you to lose interest in the very meal you grew up on. With novelty, there is no singular level of Scoville Heat Unit (SHU) that is best. You’ve got to match the heat with the situation. Is it time to improve things a bit with a smokey, yet subtle, chipotle? Or, is it time to submerge things in pure capsaicin and blow the roof off? The good news is the bad news – it’s your choice.

With novelty, you can choose subtle or spicy. Choose wisely.

And like with hot sauce, novelty doesn’t always mix well with everything else on the plate. At the picnic, when you load your plate with chicken wings, pork ribs, and apple pie, it’s best to keep the hot sauce away from the apple pie. Said more strongly, with novelty, it’s best to use separate plates. Separate the teams – one team to do heavy novelty work, the disruptive work, to obsolete the status quo, and a separate team to the lighter novelty work, the continuous improvement work, to enhance the existing offering.

Like with hot sauce, different people have different tolerance levels for novelty. For a given novelty level, one person can be excited while another can be scared. And both are right. There’s no sense in trying to change a person’s tolerance for novelty, they either like it or they don’t. Instead of trying to teach them to how to enjoy the hottest hot sauce, it’s far more effective to choose people for the project whose tolerance for novelty is in line with the level of novelty required by the project.

Some people like habanero hot sauce, and some don’t. And it’s the same with novelty.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski