Archive for the ‘One Page Thinking’ Category

With Innovation, It’s Trust But Verify.

Your best engineer walks into your office and says, “I have this idea for a new technology that could revolutionize our industry and create new markets, markets three times the size of our existing ones.” What do you do? What if, instead, it’s a lower caliber engineer that walks into your office and says those same words? Would you do anything differently? I argue you would, even though you had not heard the details in either instance. I think you’d take your best engineer at her word and let her run with it. And, I think you’d put less stock in your lesser engineer, and throw some roadblocks in the way, even though he used the same words. Why? Trust.

Your best engineer walks into your office and says, “I have this idea for a new technology that could revolutionize our industry and create new markets, markets three times the size of our existing ones.” What do you do? What if, instead, it’s a lower caliber engineer that walks into your office and says those same words? Would you do anything differently? I argue you would, even though you had not heard the details in either instance. I think you’d take your best engineer at her word and let her run with it. And, I think you’d put less stock in your lesser engineer, and throw some roadblocks in the way, even though he used the same words. Why? Trust.

Innovation is largely a trust-based sport. We roll the dice on folks that have already put it on the table, and, conversely, we raise the bar on those that have not yet delivered – they have not yet earned our trust. Seems rational and reasonable – trust those who have earned it. But how did they earn your trust the first time, before they delivered? Trust.

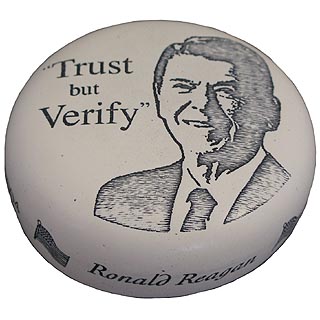

There is no place for trust in the sport of innovation. It’s unhealthy. Ronald Reagan had it right:

Trust, but verify.

As we know, he really meant there was no place for trust in his kind of sport. Every action, every statement had to be verified. The consequences so cataclysmic, no risk could be tolerated. With innovation consequences are not as severe, but they are still substantial. A three year, multi-million (billion?) dollar innovation project that returns nothing is substantial. Why do we tolerate the risk that comes with our trust-based approach? I think it’s because we don’t think there’s a better way. But there is. What we need is some good, old-fashioned verification mixed in with our innovation.

When the engineer comes into your office and says she can reinvent your industry, what do you ask yourself? What do you want to verify? You want to know if the new idea is worth a damn, if it will work, if there are fundamental constraints in the way. But, unfortunately for you, verification requires knowledge of the physics, and you’re no physicist. However, don’t lose hope. There are two simple tactics, non-technical tactics, to help with this verification business.

First – ask the engineers a simple question, “What conflict is eliminated with the new technology?” Good, innovative technologies eliminate fundamental, long standing conflicts. These long standing conflicts limit a technology in a way that is so fundamental engineers don’t even know they exist. When a fundamental conflict is eliminated, long held “design tradeoffs” no longer apply, and optimizing is replaced by maximizing. With optimizing, one aspect of the design is improved at the expense of another. With maximizing, both aspects of the design are improved without compromise. If the engineers cannot tell you about the conflict they’ve eliminated, your trust has not been sufficiently verified. Ask them to come back when they can answer your question.

Second – when they come back with their answer, it will be too complex to be understood, even by them. Tell them to come back when they can describe the conflict on a single page using a simple block diagram, where the blocks, labeled with everyday nouns, represent parts of the design intimately involved with the conflict, and the lines, labeled with everyday verbs, represent actions intimately involved with the conflict. If they can create a block diagram of the conflict, and it makes sense to you, your trust has been sufficiently verified. (For a post with a more detailed description of the block diagrams, click on “one page thinking” in the Category list.)

Though your engineers won’t like it at first, your two-pronged verification tactics will help them raise their game, which, in turn, will improve the risk/reward ratio of your innovation work.

Innovation, Technical Risk, and Schedule Risk

There is a healthy tension between level of improvement, or level of innovation, and time to market. Marketing wants radical improvement, infinitely short project schedules, and no change to the product. Engineers want to sign up for the minimum level of improvement, project schedules sufficiently long to study everything to death, and want to change everything about the new product. It’s healthy because there is balance – both are pulling equally hard in opposite directions and things end up somewhere in the middle. It’s not a stress-free environment, but it’s not too bad. But, sometimes the tension is unhealthy.

There are two flavors of unhealthy tension. First is when engineering has too much pull; they (we) sandbag on product performance and project timelines and change the design willy-nilly simply because they can (and it’s fun). The results are long project timelines, highly innovative designs that don’t work well, a lack of product robustness, and a boatload of new parts and assemblies. (Product complexity.) Second is when Marketing has too much pull; they ask for radical improvement in product functionality with project timelines too short for the level of innovation, and tightly constrain product changes such that solutions are not within the constraints. The results are long project timelines and un-innovative designs that don’t meet product specifications. (The solutions are outside the constraints.) Both sides are at fault in both scenarios. There are no clean hands.

What are the fundamentals behind all this gamesmanship? For engineering it’s technical risk; for marketing it’s schedule risk. Engineering minimizes what it signs up for in order to reduce technical risk and petitions for long project timelines to reduce it. Marketing minimizes product changes (constraints) to reduce schedule risk and petitions for short project timelines to reduce it. (Product development teams work harder with short schedules.) Something’s got to change. Read the rest of this entry »

Problems are good

Everyone laughs at the person who says “We don’t have problems, we have opportunities.” Why do we say that? We know that’s crap. We have problems; problems are real; and it’s okay to call them by name. In fact, it’s healthy. Problems are good. Problems focus our thinking. There is a serious and important nature to the word problem, and it sets the right tone. Everyone knows if the situation has risen to the level of a problem it’s important and action must be taken. People feel good about organizing themselves around a problem – problems help rally the troops.

In a previous post on innovation, I talked about the tight linkage between problems and innovation. In the pre-innovation state there is a problem; in the post-innovation state there is no problem. The work in the middle is a good description of the thing we call innovation. It could also be called problem solving.

Behind every successful product launch is a collection of solved problems. The engineering team defines the problems, understands the physics, changed the design, and makes problems go away. Behind every unsuccessful product launch is at least one unsolved problem. These unsolved problems disrupt product launches – limiting product function, delaying launches, and cancelling others altogether. All this can be caused by a single unsolved problem. Read the rest of this entry »

Engineering your way out of the recession

Like you, I have been thinking a lot about the recession. We all want to know how to move ourselves to the other side, where things are somewhat normal (the old normal, not the new one). Like usual, my mind immediately goes to products. To me, having the right products is vital to pulling ourselves out of this thing. There is nothing novel in this thinking; I think we all agree that products are important. But, there are two follow-on questions that are important. First, what makes products “right” to move you quickly to the other side? Second, do you have the capability to engineer the “right” products?

Like you, I have been thinking a lot about the recession. We all want to know how to move ourselves to the other side, where things are somewhat normal (the old normal, not the new one). Like usual, my mind immediately goes to products. To me, having the right products is vital to pulling ourselves out of this thing. There is nothing novel in this thinking; I think we all agree that products are important. But, there are two follow-on questions that are important. First, what makes products “right” to move you quickly to the other side? Second, do you have the capability to engineer the “right” products?

The first question – what makes products “right” for these times? Capacity is important to understanding what makes products right. Capacity utilization is at record lows with most industries suffering from a significant capacity glut. With decreased sales and idle machines, customers are no longer interested in products that improve productivity of their existing product lines because they can simply run their idle machines more. And, they are not interested in buying more capacity (your products) at a reduced price. They will simply run their idle machines more. You can’t offer an improvement of your same old product that enables customers to make their same old products a bit faster and you can’t offer them your same old products at a lower price. However, you can sell them products that enable them to capture business they currently do not have. For example, enable them to manufacture products that their idle machines CANNOT make at all. To do that means your new products must do something radically different than before; they must have radically improved functionality or radically new features. This is what makes products right for these times.

On to the second question – do you have the capability to engineer the right products? Read the rest of this entry »

Can CEOs meaningfully guide technology work?

Leading, shaping, and guiding technology work is hard, even for technologists who spend all day doing it. So, it seems the all-too-busy CEOs don’t stand a chance at effectively shaping their companies’ technical work. And it’s not just the non-technologist CEOs who have a problem; the technologist CEOs also have a problem, as they don’t have sufficient time to dig deeply into the details or stay current on the state-of-the-art. So, as a CEO, technologist or not, it is difficult to meaningfully lead, shape, and guide technical work.

Leading, shaping, and guiding technology work is hard, even for technologists who spend all day doing it. So, it seems the all-too-busy CEOs don’t stand a chance at effectively shaping their companies’ technical work. And it’s not just the non-technologist CEOs who have a problem; the technologist CEOs also have a problem, as they don’t have sufficient time to dig deeply into the details or stay current on the state-of-the-art. So, as a CEO, technologist or not, it is difficult to meaningfully lead, shape, and guide technical work.

So why is this technology stuff so hard to shape and guide? Well, here are a few reasons: technologies have their own set of arcane languages, each with many dialects (and no dictionary); they have their own technology-centric acronyms that technologists mix and match as they see fit; and they are full of long-forgotten formulae. And these formulae are composed of strange math shapes and symbols. And, as if to elevate confusion to stratospheric levels, the math symbols are Greek letters. So, literally, this technology stuff is written in Greek. So what’s an all-too-busy CEO to do? Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski