Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

Four Things That Matter

Health matters. What did you do this year to take care of your physical health? What did you do this year to take care of your mental health? Next year what can you stop doing to make it easier to take care of your physical and mental health? Without your health, what do you have?

Health matters. What did you do this year to take care of your physical health? What did you do this year to take care of your mental health? Next year what can you stop doing to make it easier to take care of your physical and mental health? Without your health, what do you have?

Family matters. What did you do this year to connect more deeply with your family? And how do you feel about that? Next year what can you change to make it easier to deepen your relationships with a couple of family members? If you’re going to forgive anyone next year, why not forgive a family member? Without family, what do you have?

Friends matter. What did you do this year to reconnect with old friends? What did you do this year to help turn a good friendship into a great one? What did you do this year to make new friends? Next year what will make it easier to reestablish old friendships, deepen the good ones, and create new ones? Without friends, what do you have?

Fun matters. What did you do this year to have fun for fun’s sake? Why is it so difficult to have fun? Next year what can you change to make it easier for you to have more fun? Without fun, what do you have?

“Friendship” by *~Dawn~* is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Reducing Time To Market vs. Improving Profits

X: We need to decrease the time to market for our new products.

X: We need to decrease the time to market for our new products.

Me: So, you want to decrease the time it takes to go from an idea to a commercialized product?

X: Yes.

Me: Okay. That’s pretty easy. Here’s my idea. Put some new stickers on the old product and relaunch it. If we change the stickers every month, we can relaunch the product every month. That will reduce the time to market to one month. The metrics will go through the roof and you’ll get promoted.

X: That won’t work. The customers will see right through that and we won’t sell more products and we won’t make more money.

Me: You never said anything about making more money. You said you wanted to reduce the time to market.

X: We want to make more money by reducing time to market.

Me: Hmm. So, you think reducing time to market is the best way to make more money?

X: Yes. Everyone knows that.

Me: Everyone? That’s a lot of people.

X: Are you going to help us make more money by reducing time to market?

Me: I won’t help you with both. If you had to choose between making more money and reducing time to market, which would you choose?

X: Making money, of course.

Me: Well, then why did you start this whole thing by asking me for help improving time to market?

X: I thought it was the best way to make more money.

Me: Can we agree that if we focus on making more money, we have a good chance of making more money?

X: Yes.

Me: Okay. Good. Do you agree we make more money when more customers buy more products from us?

X: Everyone knows that.

Me: Maybe not everyone, but let’s not split hairs because we’re on a roll here. Do you agree we make more money when customers pay more for our products?

X: Of course.

Me: There you have it. All we have to do is get more customers to buy more products and pay a higher price.

X: And you think that will work better than reducing time to market?

Me: Yes.

X: And you know how to do it?

Me: Sure do. We create new products that solve our customers’ most important problems.

X: That’s totally different than reducing time to market.

Me: Thankfully, yes. And far more profitable.

X: Will that also reduce the time to market?

Me: I thought you said you’d choose to make more money over reducing time to market. Why do you ask?

X: Well, my bonus is contingent on reducing time to market.

Me: Listen, if the previous new product development projects took two years, and you reduce the time to market to one and half years, there’s no way for you to decrease time to market by the end of the year to meet your year-end metrics and get your bonus.

X: So, the metrics for my bonus are wrong?

Me: Right.

X: What should I do?

Me: Let’s work together to launch products that solve important customer problems.

X: And what about my bonus?

Me: Let’s not worry about the bonus. Let’s worry about solving important customer problems, and the bonuses will take care of themselves.

Image credit — Quinn Dombrowski

X: Me: format stolen from @swardley. Thank you, Simon.

Which new product development project should we do first?

X: Of the pool of candidate new product development projects, which project should we do first?

X: Of the pool of candidate new product development projects, which project should we do first?

Me: Let’s do the one that makes us the most money.

X: Which project will make the most money?

Me: The one where the most customers buy the new product, pay a reasonable price, and feel good doing it.

X: And which one is that?

Me: The one that solves the most significant problem.

X: Oh, I know our company’s most significant problem. Let’s solve that one.

Me: No. Customers don’t care about our problems, they only care about their problems.

X: So, you’re saying we should solve the customers’ problem?

Me: Yes.

X: Are you sure?

Me: Yes.

X: We haven’t done that in the past. Why should we do it now?

Me: Have your previous projects generated revenue that met your expectations?

X: No, they’ve delivered less than we hoped.

Me: Well, that’s because there’s no place for hope in this game.

X: What do you mean?

Me: You can’t hope they’ll buy it. You need to know the customers’ problems and solve them.

X: Are you always like this?

Me: Only when it comes to customers and their problems.

image credit: Kyle Pearce

It’s not so easy to move manufacturing work back to the US.

I hear it’s a good idea to move manufacturing work back to the US.

Before getting into what it would take to move manufacturing work back to the US, I think it’s important to understand why manufacturing companies moved their work out of the US. Simply put, companies moved their work out of the US because their accounting systems told them they would make more money if they made their products in countries with lower labor costs. And now that labor costs have increased in these no longer “low-cost countries”, those same accounting systems think there’s more money to be made by bringing manufacturing back to the US.

At a low level of abstraction, manufacturing, as a word, is about making discrete parts like gears, fenders, and tires using machines like gear shapers, stamping machines, and injection molding machines. The cost of manufacturing the parts is defined by the cost of the raw material, the cost of the machines, the cost of energy to power the machines, the cost of the factory, and the cost of the people to run the machines. And then there’s assembly, which, as a word, is about putting those discrete parts together to make a higher-level product. Where manufacturing makes the gears, fenders, and tires, assembly puts them together to make a car. And the cost of assembly is defined by the cost of the factory, the cost of fixtures, and the cost of the people to assemble the parts into the product. And the cost of the finished product is the sum of the cost of making the parts (manufacturing) and the cost of putting them together (assembly).

It seems pretty straightforward to make more money by moving the manufacturing of discrete parts back to the US. All that has to happen is to find some empty factory space, buy new machines, land them in the factory, hire the people to run the machines, train them, source the raw material, hire the manufacturing experts to reinvent/automate the manufacturing process to reduce cycle time and reduce labor time and then give them six months to a year to do that deep manufacturing work. That’s quite a list because there’s little factory space available that’s ready to receive machines, the machines cost money, there are few people available to do manufacturing work, the cost to train them is high (and it takes time and there are no trained trainers). But the real hurdles are the deep work required to reinvent/automate the process and the lack of manufacturing experts to do that work. The question you should ask is – Why does the manufacturing process have to be reinvented/automated?

There’s a dirty little secret baked into the accounting systems’ calculations. The cost accounting says there can be no increased profit without reducing the time to make the parts and reducing the labor needed to make them. If the work is moved from country A to country B and the costs (cycle time, labor hours, labor rate) remain constant, the profit remains constant. Simply moving from country A to country B does nothing. Without the deep manufacturing work, profits don’t increase. And if your country doesn’t have the people with the right expertise, that deep manufacturing work cannot happen.

And the picture is similar for moving assembly work back to the US. All that has to happen is to find empty factory space, hire and train people to do the assembly work, reroute the supply chains to the new factory, redesign the product so it can be assembled with an automated assembly line, hire/train the people to redesign the product so it can be assembled in an automated way, design the new automated assembly process, build it, test it, hire/train the automated assembly experts to do that work, hire the people to support and run the automated assembly line, and pay for the multi-million-dollar automated assembly line. And the problems are similar. There’s not a lot of world-class factory space, there are few people available to run the automated assembly line, and the cost of the automated assembly line is significant. But the real problems are the lack of experts to redesign the product for automated assembly and the lack of expertise to design, build, and validate the assembly line. And here are the questions you should ask – Why do we need to automate the assembly process and why does the product have to be redesigned to do that?

It’s that dirty little secret rearing its ugly head again. The cost accounting says there can be no increased profit without reducing the labor to assemble the parts. make them. If the work is moved from country A to country B and the assembly costs (labor hours, labor rate) remain constant, the profit remains constant. Simply moving from country A to country B does nothing. Without deep design work (design for automated assembly) and ultra-deep automated assembly work, profits don’t increase. And if your country doesn’t have the people with the right expertise, that deep design and automated assembly work cannot happen.

If your company doesn’t have the time, money, and capability to reinvent/automate manufacturing processes, it’s a bad idea to move manufacturing work back to the US. It simply won’t work. Instead, find experts who can help you develop/secure the capability to reinvent/automate manufacturing processes to reduce the cost of manufacturing.

If your company doesn’t have the time, money, and capability to design products for automated assembly and to design, build, and validated automated assembly systems, it’s a bad idea to move assembly work back to the US. It, too, simply won’t work. Instead, partner with experts who know how to do that work so you can reduce the cost of assembly.

Short Lessons

Show customers what’s possible. Then listen.

Show customers what’s possible. Then listen.

The best projects are small until they’re not.

Today’s location before tomorrow’s destination.

The best idea requires the least effort.

Ready, fire, aim is better than ready, aim, aim, aim.

Be certain about the uncertainty.

Do so you can discuss.

Put it on one page.

Fail often, but call it learning.

Current state before future state.

Say no now to say yes later.

Effectiveness over efficiency.

Finish one to start one.

Demonstrate before asking.

Sometimes slower is faster.

Build trust before you need it.

“Yin & Yang martini” by AMagill is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Three Important Choices for New Product Development Projects

Choose the right project. When you say yes to a new project, all the focus is on the incremental revenue the project will generate and none of the focus is on unrealized incremental revenue from the projects you said no to. Next time there’s a proposal to start a new project, ask the team to describe the two or three most compelling projects that they are asking the company to say no to. Grounding the go/no-go decision within the context of the most compelling projects will help you avoid the real backbreaker where you consume all your product development resources on something that scratches the wrong itch while you prevent those resources from creating something magical.

Choose the right project. When you say yes to a new project, all the focus is on the incremental revenue the project will generate and none of the focus is on unrealized incremental revenue from the projects you said no to. Next time there’s a proposal to start a new project, ask the team to describe the two or three most compelling projects that they are asking the company to say no to. Grounding the go/no-go decision within the context of the most compelling projects will help you avoid the real backbreaker where you consume all your product development resources on something that scratches the wrong itch while you prevent those resources from creating something magical.

Choose what to improve. Give your customers more of what you gave them last time unless what you gave them last time is good enough. Once goodness is good enough, giving customers more is bad business because your costs increase but their willingness to pay does not. Once your offering meets the customers’ needs in one area, lock it down and improve a different area.

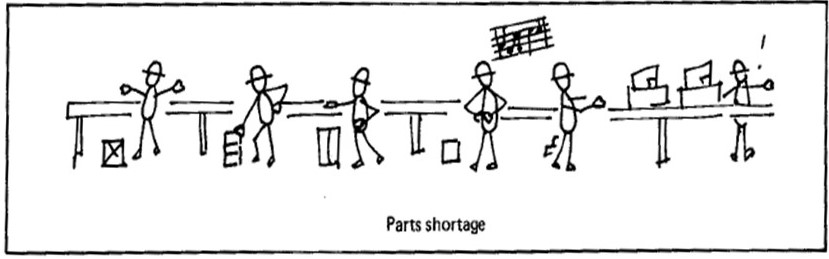

Choose how to staff the projects. There is a strong temptation to run many projects in parallel. It’s almost like our objective is to maximize the number of active projects at the expense of completing them. Here’s the thing about projects – there is no partial credit for partially completed projects. Eight active projects that are eight (or eighty) percent complete generate zero revenue and have zero commercial value. For your most important project, staff it fully. Add resources until adding more resources would slow the project. Then, for your next most important project, repeat the process with your remaining resources. And once a project is completed, add those resources to the pool and start another project. This approach is especially powerful because it prioritizes finishing projects over starting them.

“Three Cows” by Sunfox is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Speaking your truth is objective evidence you care.

When you see something, do you care enough to say something?

When you see something, do you care enough to say something?

If you disagree, do you care enough to say it out loud?

When the emperor has no clothes, do you care enough to hand them a cover-up?

Cynicism is grounded in caring. Do you care enough to be cynical?

Agreement without truth is not agreement. Do you care enough to disagree?

Violation of the status quo creates conflict. Do you care enough to violate?

If you care, speak your truth.

“Great Grey Owl (Strix nebulosa)” by Bernard Spragg is marked with CC0 1.0.

Radical Cost Reduction and Reinvented Supply Chains

As geopolitical pressures rise, some countries that supply the parts that make up your products may become nonviable. What if there was a way to reinvent the supply chain and move it to more stable regions? And what if there was a way to guard against the use of child labor in the parts that make up your product? And what if there was a way to shorten your supply chain so it could respond faster? And what if there was a way to eliminate environmentally irresponsible materials from your supply chain?

As geopolitical pressures rise, some countries that supply the parts that make up your products may become nonviable. What if there was a way to reinvent the supply chain and move it to more stable regions? And what if there was a way to guard against the use of child labor in the parts that make up your product? And what if there was a way to shorten your supply chain so it could respond faster? And what if there was a way to eliminate environmentally irresponsible materials from your supply chain?

Our supply chains source parts from countries that are less than stable because the cost of the parts made in those countries is low. And child labor can creep into our supply chains because the cost of the parts made with child labor is low. And our supply chains are long because the countries that make parts with the lowest costs are far away. And our supply chains use environmentally irresponsible materials because those materials reduce the cost of the parts.

The thing with the supply chains is that the parts themselves govern the manufacturing processes and materials that can be used, they dictate the factories that can be used and they define the cost. Moving the same old parts to other regions of the world will do little more than increase the price of the parts. If we want to radically reduce cost and reinvent the supply chain, we’ve got to reinvent the parts.

There are methods that can achieve radical cost reduction and reinvent the supply chain, but they are little known. The heart of one such method is a functional model that fully describes all functional elements of the system and how they interact. After the model is complete, there is a straightforward, understandable, agreed-upon definition of how the product functions which the team uses to focus the go-forward design work. And to help them further, the method provides guidelines and suggestions to prioritize the work.

I think radical cost reduction and more robust supply chains are essential to a company’s future. And I am confident in the ability of the methods to deliver solid results. But what I don’t know is: Is the need for radical cost reduction strong enough to cause companies to adopt these methods?

“Zen” by g0upil is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Three Scenarios for Scaling Up the Work

Breaking up work into small chunks can be a good way to get things started. Because the scope of each chunk is small, the cost of each chunk is small making it easier to get approval to do the work. The chunk approach also reduces anxiety around the work because if nothing comes from the chunk, it’s not a big deal because the cost of the work is so low. It’s a good way to get started, and it’s a good way to do a series of small chunks that build on each other. But what happens when the chunks are successful and it’s time to scale up the investment by a factor of several hundred thousand or a million?

Breaking up work into small chunks can be a good way to get things started. Because the scope of each chunk is small, the cost of each chunk is small making it easier to get approval to do the work. The chunk approach also reduces anxiety around the work because if nothing comes from the chunk, it’s not a big deal because the cost of the work is so low. It’s a good way to get started, and it’s a good way to do a series of small chunks that build on each other. But what happens when the chunks are successful and it’s time to scale up the investment by a factor of several hundred thousand or a million?

The scaling scenario. When the early work (the chunks) was defined an agreement in principle was created that said the larger investment would be made in a timely way if the small chunks demonstrated the viability of a whole new offering for your customers. The result of this scenario is a large investment is allocated quickly, resources flow quickly, and the scaling work begins soon after the last chunk is finished. This is the least likely scenario.

The more chunks scenario. When the chunks were defined, everyone was excited that the novel work had actually started and there was no real thought about the resources required to scale it into something meaningful and material. Since the resources needed to scale were not budgeted, the only option to keep things going is to break up the work into another series of small chunks. Though the organization sees this as progress, it’s not. The only thing that can deliver the payout the organization needs is to scale up the work. The follow-on chunks distract the company and let it think there is progress, when, really, there is only delayed scaling.

The scale next year scenario. When the chunks were defined, no one thought about scaling so there was no money in the budget to scale. A plan and cost estimate are created for the scaling work and the package waits to be assessed as part of the annual planning process. And as the waiting happens, the people that did the early work (the chunks) move on to other projects and are not available to do the scaling work even if the work gets funded next year. And because the work is new it requires new infrastructure, new resources, new teams, new thinking, and maybe a new company. All this newness makes the price tag significant and it may require more than one annual planning cycle to justify the expense and start the work.

Scaling a new invention into a full-sized business is difficult and expensive, but if you’re looking to create radical growth, scaling is the easiest and least expensive way to go.

“100 Dollar Bills” by Philip Taylor PT is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

How To Complete More Projects

Before you decide which project to start, decide which project you’ll stop.

Before you decide which project to start, decide which project you’ll stop.

The best way to stop a project is to finish it. The next best way is to move the resources to a more important project.

If you find yourself starting before finishing, stop starting and start finishing.

People’s output is finite. Adding a project that violates their human capacity will not result in more completed projects but will cause your best people to leave.

If people’s calendars are full, the only way to start something new is to stop something old.

If you start more projects than you finish, you’re stopping projects before they’re finished. You’re probably not stopping them in an official way, rather, you’re letting them wither and die a slow death. But you’re definitely stopping them.

When you start more projects than you finish, the number of active projects increases. And without a corresponding increase in resources, fewer projects are completed.

The best way to reduce the number of projects you finish is to start new projects.

Make a list of the projects that you stopped over the last year. Is it a short list?

Make a list of projects that are understaffed and under-resourced yet still running in the background. Is that list longer?

A rule to live by: If a project is understaffed, staff it or stop it.

If you can’t do that, reduce the scope to fit the resources or stop it.

Would you prefer to complete one project at a time or do three simultaneously and complete none?

When it comes to stopping projects, it’s stopped or it isn’t. There’s no partial credit for talking about stopping a project.

If you want to learn if a project is worthy of more resources, stop the project. If the needed resources flow to the project, the project is worthy. If not, at least you stopped a project that shouldn’t have been started.

People don’t like working on projects where the work content is greater than the resources to do the work. These projects are a major source of burnout.

If you know you have too many projects, everyone else knows it too. Stop the weakest projects or your credibility will suffer.

“Circus Renz Berlin, Holland 2011” by dirkjanranzijn is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

It’s good to have experience, until the fundamentals change.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

The system works well when we correctly match the historical context with today’s context and the system’s fundamentals remain unchanged. There are two potential failure modes here. The first is when we mistakenly map the context of today’s situation with a memory-context pair that does not apply. With this, we misapply our experience-based knowledge in a context that demands different knowledge and different decisions. The second (and more dangerous) failure mode is when we correctly identify the match between past and current contexts but the rules that underpin the context have changed. Here, we feel good that we know how things will turn out, and, at the same time, we’re oblivious to the reality that our experience-based knowledge is out of date.

“If a cat sits on a hot stove, that cat won’t sit on a hot stove again. That cat won’t sit on a cold stove either. That cat just don’t like stoves.” Mark Twain

If you tried something ten years ago and it failed, it’s possible that the underpinning technology has changed and it’s time to give it another try.

If you’ve been successful doing the same thing over the last ten years, it’s possible that the underpinning business model has changed and it’s time to give a different one a try.

“Hissing cat” by Consumerist Dot Com is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski