Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

Your Words Make All The Difference.

Sometimes people are unskillful with their words, and what they say can have multiple interpretations. But, though you don’t have control over their words, you do have control over how you interpret them. And the translation you choose makes all the difference. On the flipside, when you choose your words skillfully they can have a singular translation. And that, too, makes all the difference. Here are some examples.

Sometimes people are unskillful with their words, and what they say can have multiple interpretations. But, though you don’t have control over their words, you do have control over how you interpret them. And the translation you choose makes all the difference. On the flipside, when you choose your words skillfully they can have a singular translation. And that, too, makes all the difference. Here are some examples.

It can’t be done. Translations: 1) We’ve never tried it and we don’t know how to go about it. 2) We know you’ll not give us the time and the resources to do it right, and because of that, we won’t be successful. 3) Wow. I like that idea, but we’re already so overloaded. Do you think we can talk about that in the second half of the year?

We tried that but it didn’t work. Translations: 1) Twelve years ago someone who made a prototype and it worked pretty well. But, she wasn’t given the time to take it to the next level and the project was abandoned. 2) We all think that’s a wonderful idea and really want to work on it, but we’re too busy to think about that. If I come clean, will you give me the resources to do it right?

Why didn’t you follow the best practice? Translations: 1) I’m afraid of the uncertainty around this innovation work and I’ve heard best practices can reduce risk. 2) I don’t really know what I’m talking about, but this seems like a safe question to ask without tipping my hand. 3) I want to make a difference at the company, but I’ve never been part of a project with so much newness. Can you teach me?

That’s not how we do it. Translations: 1) I’ve always done it that way, and thinking about doing it differently scares me. 2) Though the process is clunky, we’ve been told to follow it. And I don’t want to get in trouble. 3) That sounds like a good idea, but I don’t have the time to think through the potential implications to our customers.

What are you working on? Translation: I’m interested in what you’re working on because I care about you.

Can I help you? Translation: You’ve helped me in the past and I see you’re in a tough situation. I care about you. What can I do to help?

Good job. Translation: I want to positively reinforce your good work in front of everyone because, well, you did good work.

That’s a good idea. Translation: I think highly of you, I like that you stuck out your neck, and I hope you do it regularly.

I need help. Translation: I know you are highly capable and I trust you. I’m in a tight spot here. Can you help me?

Thank you. Translation: You were helpful and I appreciate it. Thank you.

How you choose your words and how you choose to assign meaning to others’ words make all the difference. Choose skillfully.

image credit — woodleywonderworks

You don’t find the next new thing, it finds you.

Doing something new is harder than it looks.

Doing something new is harder than it looks.

The first step to doing new is to realize you have no interest in doing what was done last time. Profitable or not, the same old recipe just doesn’t do it for you. You don’t have to know why you don’t want to replay the tape, you just have to know you don’t want to. So don’t.

But it’s not enough to know what you don’t want to do, you’ve got to know what you do want to do. To figure that out, you’ve got to stop doing. The focused, churning mind isn’t your friend here because it thinks of ideas that are too closely related to what it knows. This is the job for the idle mind. The idle mind has nothing to focus on, so it doesn’t. It runs in the background imagining the impossible and considering the absurd. And since it runs without your knowledge, you can’t get in its way. So do nothing. Turn off your electronics and sit. Feel uncomfortable. Give your mind no place to go so it can go where it wants. Read a biography about an important historical figure. Travel to their century so while you’re visiting your subconscious can figure out what to do.

You don’t figure out what’s next. What’s next finds you while you’re not looking for it. And the best way to do that is to do nothing.

Doing nothing is a lot of work. And it’s difficult to do. My advice – start with 15 minutes of nothing. Anything more is too much. Take your mobile phone out of your pocket, put it on your desk (or throw it at the floor and stomp on it) and walk to a quiet place and sit. Close your eyes, sit and watch. You’ll see your monkey mind search for the next big thing and not find it. Then you’ll see it think about something that scares you and you’ll get scared. Then you’ll see it think about an old argument and you’ll jump back into it and relive it. Then, after a while, you’ll realize you’re not watching, you’re reliving. Then you’ll see your mind try again in vain to find the next thing to do. And after 15 minutes of this nonsense, you’re done with your first session of nothing.

Repeat this process over 5 days and a good idea will find you. You may be sleeping, showering, eating or reading, but no worries, it will find you. Something will click and you’ll put together two things that aren’t meant to be together but, once together, make a lot of sense – like a strange Ben and Jerry’s flavor you taste for the first time and eat the whole pint.

The new idea isn’t the new thing itself, it’s the first step toward finding the next thing to do. But, you’ve started wandering down a crazy new path that’s no longer crazy, and you’re on your way.

Resume your daily 15 minute sessions of nothing and, in between, mix in some small experiments to test, refine or invalidate your next new thing. Repeat, as needed.

And don’t stop until what you’re looking for finds you.

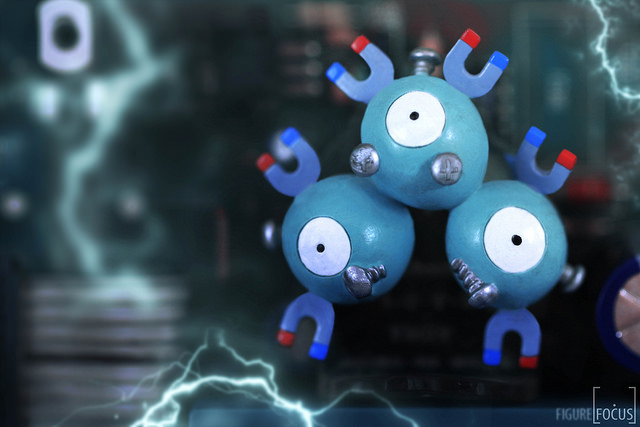

Image credit – Figure Focus.

Creating a brand that lasts.

One of the best ways to improve your brand is to improve your products. The most common way is to provide more goodness for less cost – think miles per gallon. Usually it’s a straightforward battle between market leaders, where one claims quantifiable benefit over the other – Ours gets 40 mpg and theirs doesn’t. And the numbers are tied to fully defined test protocols and testing agencies to bolster credibility. Here’s the data. Buy ours

One of the best ways to improve your brand is to improve your products. The most common way is to provide more goodness for less cost – think miles per gallon. Usually it’s a straightforward battle between market leaders, where one claims quantifiable benefit over the other – Ours gets 40 mpg and theirs doesn’t. And the numbers are tied to fully defined test protocols and testing agencies to bolster credibility. Here’s the data. Buy ours

But there’s a more powerful way to improve your brand, and that’s to map your products to reliability. It’s far a more difficult game than the quantified head-to-head comparison of fuel economy and it’s a longer play, but done right, it’s a lasting play that is difficult to beat. Run the thought experiment: think about the brands you associate with reliability. The brands that come to mind are strong, lasting brands, brands with staying power, brands whose products you want to buy, brands you don’t want to compete against. When you buy their products you know what you’re going to get. Your friends tell you stories about their products.

There’s a complete a complete tool set to create products that map to reliability, and they work. But to work them, the commercialization team has to have the right mindset. The team must have the patience to formally define how all the systems work and how they interact. (Sounds easy, but it can be painfully time consuming and the level of detail is excruciatingly extreme.) And they have to be willing to work through the discomfort or developing a common understanding how things actually work. (Sounds like this shouldn’t be an issue, but it is – at the start, everyone has a different idea on how the system works.) But more importantly, they’ve got to get over the natural tendency to blame the customer for using the product incorrectly and learn to design for unintended use.

The team has got to embrace the idea that the product must be designed for use in unpredictable ways in uncontrolled conditions. Where most teams want to narrow the inputs, this team designs for a wider range of inputs. Where it’s natural to tighten the inputs, this team designs the product to handle a broader set of inputs. Instead of assuming everything will work as intended, the team must assume things won’t work as intended (if at all) and redesign the product so it’s insensitive to things not going as planned. It’s strange, but the team has to design for hypothetical situations and potential problems. And more strangely, it’s not enough to design for potential problems the team knows about, they’ve got to design for potential problems they don’t know about. (That’s not a typo. The team must design for failure modes it doesn’t know about.)

How does a team design for failure modes it doesn’t know about? They build a computer-based behavioral model of the system, right down to the nuts, bolts and washers, and they create inputs that represent the environment around the system. They define what each element does and how it connects to the others in the system, capturing the governing physics and propagation paths of connections. Then they purposefully break the functions using various classes of failure types, run the analysis and review the potential causes. Or, in the reverse direction, the team perturbs the system’s elements with inputs and, as the inputs ripple through the design, they find previously unknown undesirable (harmful) functions.

Purposefully breaking the functions in known ways creates previously unknown potential failure causes. The physics-based characterization and the interconnection (interaction) of the system elements generate unpredicted potential failure causes that can be eliminated through design. In that way, the software model helps find potential failures the team did not know about. And, purposefully changing inputs to the system, again through the physics and interconnection of the elements, generates previously unknown harmful functions that can be designed out of the product.

If you care about the long-term staying power of your brand, you may want to take a look at TechScan, the software tool that makes all this possible.

Image credit — Chris Ford.

Selling New Products to New Customers in New Markets

There’s a special type of confusion that has blocked many good ideas from seeing the light of day. The confusion happens early in the life of a new technology when it is up and running in the lab but not yet incorporated in a product. Since the new technology provides a new flavor of customer goodness, it has the chance to create incremental sales for the company. But, since there are no products in the market that provide the novel goodness, by definition there can be no sales from these products because they don’t yet exist. And here’s the confusion. Organizations equate “no sales” with “no market”.

There’s a special type of confusion that has blocked many good ideas from seeing the light of day. The confusion happens early in the life of a new technology when it is up and running in the lab but not yet incorporated in a product. Since the new technology provides a new flavor of customer goodness, it has the chance to create incremental sales for the company. But, since there are no products in the market that provide the novel goodness, by definition there can be no sales from these products because they don’t yet exist. And here’s the confusion. Organizations equate “no sales” with “no market”.

There’s a lot of risk with launching new products with new value propositions to new customers. You invest resources to create the new technologies and products, create the sales tools, train the sales teams, and roll it out well. And with all this hard work and investment, there’s a chance no one will buy it. Launching a product that improves on an existing product with an existing market is far less risky – customers know what to expect and the company knows they’ll buy it. The status quo when stable if all the players launch similar products, right up until it isn’t. When an upstart enters the market with a product that offers new customer goodness (value proposition) the same-old-same-old market-customer dynamic is changed forever.

A market-busting product is usually launched by an outsider – either a big player moves into a new space or a startup launches its first product. Both the new-to-market big boy and the startup have a far different risk profile than the market leader, not because their costs to develop and launch a new product are different, but because they have not market share. For them, they have no market share to protect any new sales are incremental. But for the established players, most of their resources are allocated to protecting their existing business and any resources diverted toward a new-to-market product is viewed as a loss of protective power and a risk to their market share and profitability. And on top of that, the incumbent sees sales of the new product as a threat to sales of the existing products. There’s a good chance that their some of their existing customers will prefer the new goodness and buy the new-to-market product instead of the tried-and-true product. In that way, sales growth of their own new product is seen as an attack no their own market share.

Business leaders are smart. Theoretically, they know when a new product is proposed, because it hasn’t launched yet, there can be no sales. Yet, practically, because their prime directive to protect market share is so all-encompassing and important, their vision is colored by it and they confound “no sales” with “no market”. To move forward, it’s helpful to talk about their growth objectives and time horizon.

With a short time horizon, the best use of resources is to build on what works – to launch a product that builds on the last one. But when the discussion is moved further out in time, with a longer time horizon it’s a high risk decision to hold on tightly to what you have as the market changes around you. Eventually, all recipes run out of gas like Henry Ford’s Model T. And the best leading indicator of running low on fuel is when the same old recipe cannot deliver on medium-term growth objectives. Short term growth is still there, but further out they are not. Market forces are squeezing the juice out of your past success.

Ultimately, out of desperation, the used-to-be market leader will launch a new-to-market product. But it’s not a good idea to do this work only when it’s the only option left. Before they’re launched, new products that offer new value to customers will, by definition, have no sales. Try to hold back the fear-based declaration that there is no market. Instead, do the forward-looking marketing work to see if there is a market. Assume there is a market and build some low cost learning prototypes and put them in front of customers. These prototypes don’t yet have to be functional; they just have to communicate the idea behind the new value proposition.

Before there is a market, there is an idea that a market could exist. And before that could-be market is served, there must be prototype-based verification that the market does in fact exist. Define the new value proposition, build inexpensive prototypes and put them in front of customers. Listen to their feedback, modify the prototypes and repeat.

Instead of arguing whether the market exists, spend all your energy proving that it does.

Image credit — lensletter

Doing New Work

If you know what to do, do it. But if you always know what to do, do something else. There’s no excitement in turning the crank every-day-all-day, and there’s no personal growth. You may be getting glowing reviews now, but when your process is documented and becomes standard work, you’ll become one of the trivial many that follow your perfected recipe, and your brain will turn soggy.

If you know what to do, do it. But if you always know what to do, do something else. There’s no excitement in turning the crank every-day-all-day, and there’s no personal growth. You may be getting glowing reviews now, but when your process is documented and becomes standard work, you’ll become one of the trivial many that follow your perfected recipe, and your brain will turn soggy.

If you want to do the same things more productively, do continuous improvement. Look at the work and design out the waste. I suggest you look for the waiting and eliminate it. (One hint – look for people or parts queueing up and right in front of the pile you’ll find the waste maker.) But if you always eliminate waste, do something else. Break from the minimization mindset and create something new. Maximize something. Blow up the best practice or have the courage to obsolete your best work. In a sea of continuous improvement, be the lighthouse of doing new.

When you do something for the first time, you don’t know how to do it. It’s scary, but that’s just the feeling you want. The cold feeling in your chest is a leading indicator of personal growth. (If you don’t have a sinking feeling in your gut, see paragraph 1.) But organizations don’t make it easy to do something for the first time. The best approach is to start small. Try small experiments that don’t require approval from a budget standpoint and are safe to fail. Run the experiments under the radar and learn in private. Grow your confidence in yourself and your thinking. After you have some success, show your results to people you trust. Their input will help you grow. And you’ll need every bit of that personal growth because to staff and run a project to bring your new concept to life you’ll need resources. And for that you’ll need to dance with the most dangerous enemy of doing new things – the deadly ROI calculation.

The R is for return. To calculate the return for the new concept you need to know: how many you’ll sell, how much you’ll sell them for, how much it will cost, and how well it will work. All this must be known BEFORE resources can be allocated. But that’s not possible because the new thing has never been done before. Even before talking about investment (I), the ROI calculation makes a train wreck of new ideas. To calculate investment, you’ve got to know how many person-hours will be needed, the cost of the materials to make the prototypes and the lab resources needed for testing. But that’s impossible to know because the work has never been done before. The ROI is a meaningless calculation for new ideas and its misapplication has spelled death for more good ideas than anything else known to man.

Use the best practice and standardize the work. There’s immense pressure to repeat what was done last time because our companies prefer incremental growth that’s predictable over unreasonable growth that’s less certain. And add to that the personal risk and emotional discomfort of doing new things and it’s a wonder how we do anything new at all.

But magically, new things do bubble up from the bottom. People do find the courage to try things that obsolete the business model and deliver new lines of customer goodness. And some even manage survive the run through the ROI gauntlet. With odds stacked against them, your best people push through their fears cut through the culture of predictability.

Imagine what they will do when you demand they do new work, give them the tools, time and training to do it, and strike the ROI calculation from our vocabulary.

Image credit – Tony Sergo

Finding Your Full Potential

If you’re all sad or anxious, you’re not operating at full potential.

If you’re all sad or anxious, you’re not operating at full potential.

If you’re sad, you’re thinking about the past. You’re remembering what happened and wishing it went differently. You’re compromising the present by spending emotional energy on something that cannot change. The past is gone, never to return. Can’t unwind it, can’t undo it. Let it go. Bring your mind back to your body. It’s time to realize your potential, and the only way to do that is to live in the present.

If you’re anxious or afraid, you’re thinking about the future. You’re thinking about what may happen and imagining that it’s not going to go your way. You’re practicing failure in the future. It’s not possible to control the future, so don’t try. And don’t worry about problems that haven’t happened yet because they may not happen at all. Grab your mind and reattach it to your body because the future is not made in the future, it’s made in the present. And that’s just where you’ll find your full potential.

You operate at your full potential when you apply your full attention to the present. In the present, all your internal resources are applied to the situation at hand. If you are in a conversation with a friend, you are fully engaged and practicing full-body listening. If you are working on a problem, each hemisphere sees it from its own perspective all-the-while discussing it with its better half. Point is, you’re all-in. Point is, all of you is in the present.

When you find your mind wandering in the past, take a breath and bring it back to the present so you can get back to living at your potential. When you find your mind worrying in the future, take two breaths and head back to the home of your full potential.

Whether you find it in the past or future, just bring your mind back to the present. There’s nothing wrong with a mind that wanders. Minds wander. That’s their nature. That’s what they do. Don’t be sad and don’t worry. Just bring it back.

Image credit – TEDxPioneerValley2012

Don’t mentor. Develop young talent.

Your young talent deserves your attention. But it’s not for the sake of the young talent, it’s for the survival of your company.

Your young talent deserves your attention. But it’s not for the sake of the young talent, it’s for the survival of your company.

Your young talent understands technology far better than your senior leaders. And they don’t just know how it works, they know why people use it. And it’s not just social media. They know how to code, they know how to prototype (I think the call it hacking, or something like that.) and they know how things fit together. And they know what’s next. But they don’t know how to get things done within your organization.

Mentoring isn’t the right word. It’s a tired word without meaning, and we’ve demonstrated we care about it only from a compliance standpoint and not a content standpoint. The mentorship checklist – set up regular meetings, meet infrequently without an agenda, lie it die a slow death and then declare compliance. Nurturing is a better word, but it has connotations of taking care. Parenting captures the essence of the work, but it doesn’t fit with the language of companies. But that may not be so bad, because the work doesn’t fit with the operations companies.

In the short term it’s inefficient to spend precious leadership bandwidth on young talent, but in the long run, it’s the only way to go. Just as the yardwork goes more slowly when your kids help, the next time it’s a bit faster. But the real benefit, the unquantifiable benefit, is the pure joy of spending time with irreverent, energetic, idealistic young people. Yes, there’s less productivity (fewer leaves raked per hour), but that’s not what it’s about. There’s growth, increased capability and shared experience that will set up the next lesson.

The biggest mistake is to come up with special “mentorship projects”. Adding work for the sake of growing talent is wrong on so many levels. Instead, help them with the work they’re expected to do. Dig in. Help them. Contribute to their projects. Go to their meetings. Provide technical guidance. Look ahead for potential problems and tell them they are looming over the horizon. Let them make the decisions. Let them choose the path, but run ahead and make sure they negotiate the corner. If they’re going to make it, let them scoot through without them seeing you. If they’re going to crash, grab the wheel and negotiate the corner with them. Then, when things have calmed down, tell them why you stepped in.

Your children watch you. They watch how you interact with your spouse; they watch how you handle stressful situations; they watch how you treat other children; they listen to what you say to them; they listen to how you say it. And when the words disagree with the unsaid sentiment, they believe the sentiment. Your children know you by your actions. You are transparent to them. They know everything about you. They know why you do things and they know what you stand for. And young talent is no different.

There is nothing more invigorating than a bright, young person willing to dig in and make a difference. Their passion is priceless. And as much as you are helping them, they are helping you. They spark new thinking; they help you see the implicit assumptions you’ve left untested for too long and then naively stomp on them and give you a save-face way to revisit your old thinking. When the toddler learns to walk, even the grandparents spring to life and spryly support them step-by-step.

Don’t call it parenting, but behave like one. Take the time to form the close relationships that transcend the generational divide. Make it personal, because it is. And when you have too much to do and too little time to invest in young talent, do it anyway. Do it for them or do it for the company, but do it.

But in the end, do it for the right reason, the selfish reason – because it the best thing for you.

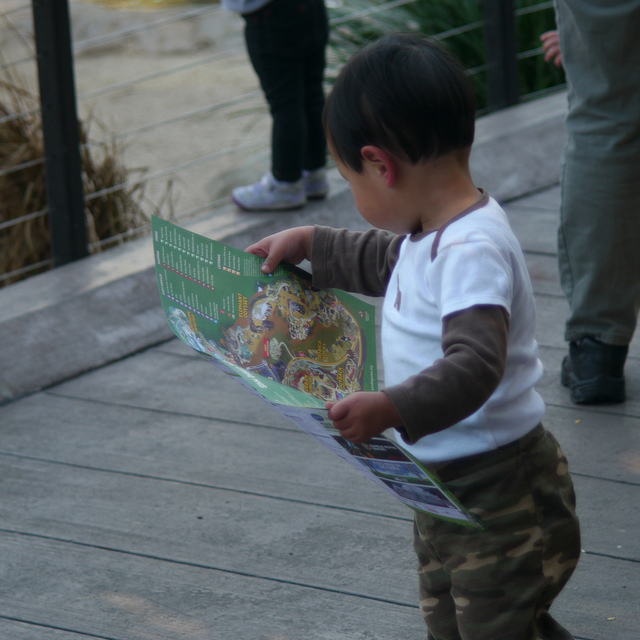

Image credit – mliu92

Step-Wise Learning

At every meeting you have a chance to move things forward or hold them back. When a new idea is first introduced it’s bare-naked. In its prenatal state, it’s wobbly and can’t stand on its own and is vulnerable to attack. But since it’s not yet developed, it’s impressionable and willing to evolve into what it could be. With the right help it can go either way – die a swift death or sprout into something magical.

At every meeting you have a chance to move things forward or hold them back. When a new idea is first introduced it’s bare-naked. In its prenatal state, it’s wobbly and can’t stand on its own and is vulnerable to attack. But since it’s not yet developed, it’s impressionable and willing to evolve into what it could be. With the right help it can go either way – die a swift death or sprout into something magical.

Early in gestation, the most worthy ideas don’t look that way. They’re ugly, ill-formed, angry or threatening. Or, they’re playful, silly or absurd. Depending on your outlook, they can be a member of either camp. And as your outlook changes, they can jump from one camp to the other. Or, they can sit with one leg in each. But none of that is about the idea, it’s all about you. The idea isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a reflection of you. The idea is nothing until you attach your feelings to it. Whether it lives or dies depends on you.

Are you looking for reasons to say yes or reasons to say no?

On the surface, everyone in the organization looks like they’re fully booked with more smart goals than they can digest and have more deliverables than they swallow, but that’s not the case. Though it looks like there’s no room for new ideas, there’s plenty of capacity to chew on new ideas if the team decides they want to. Every team can spare and hour or two a week for the right ideas. The only real question is do they want to?

If someone shows interest and initiative, it’s important to support their idea. The smallest acceptable investment is a follow-on question that positively reinforces the behavior. “That’s interesting, tell me more.” sends the right message. Next, “How do you think we should test the idea?” makes it clear you are willing to take the next step. If they can’t think of a way to test it, help them come up with a small, resource-lite experiment. And if they respond with a five year plan and multi-million dollar investment, suggest a small experiment to demonstrate worthiness of the idea. Sometimes it’s a thought experiment, sometimes it’s a discussion with a customer and sometimes it’s a prototype, but it’s always small. Regardless of the idea, there’s always room for a small experiment.

Like a staircase, a series of small experiments build on each other to create big learning. Each step is manageable – each investment is tolerable and each misstep is survivable – and with each experiment the learning objective is the same: Is the new idea worthy of taking the next step? It’s a step-wise set of decisions to allocate resources on the right work to increase learning. And after starting in the basement, with step-by-step experimentation and flight-by-flight investment, you find yourself on the fifth floor.

This is about changing behavior and learning. Behavior doesn’t change overnight, it changes day-by-day, step-by-step. And it’s the same for learning – it builds on what was learned yesterday. And as long at the experiment is small, there can be no missteps. And it doesn’t matter what the first experiment is all about, as long as you take the first step.

Your team will recognize your new behavior because it respectful of their ideas. And when you respect their ideas, you respect them. Soon enough you will have a team that stands taller and runs small experiments on their own. Their experiments will grow bolder and their learning will curve will steepen. Then, you’ll struggle to keep up with them, and you’ll have them right where you want them.

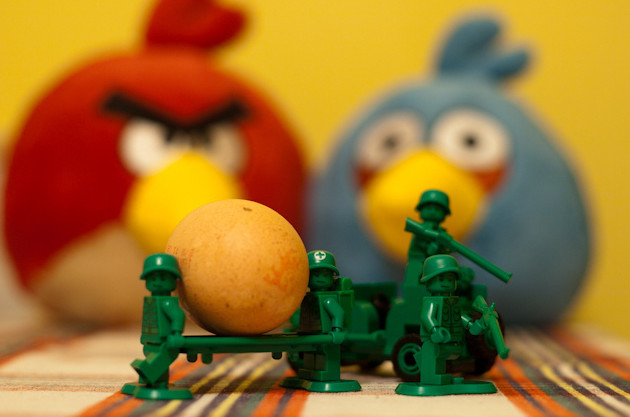

image credit — Rob Warde

There is no failure, there is only learning.

You’re never really sure how your new project will turn out, unless you don’t try. Not trying is the only way to guarantee certainty – certainty that nothing good will come of it.

You’re never really sure how your new project will turn out, unless you don’t try. Not trying is the only way to guarantee certainty – certainty that nothing good will come of it.

There’s been a lot of talk about creating a culture where failure is accepted. But, failure will never be accepted, and nor should it be. Even the failing forward flavor won’t be tolerated. There’s a skunk-like stink to the word that cannot be cleansed. Failure, as a word, should be struck from the vernacular.

If you have a good plan and you execute it well, there can be no failure. The plan can deliver unanticipated results, but that’s not failure, that’s called learning. If the team runs the same experiment three times in a row, that, too, is not failure. That’s “not learning”. The not learning is a result of something, and that something should be pursued until you learn its name and address. And once named, made to go away.

When the proposed plan is reviewed and improved before it’s carried out, that’s not failure. That’s good process that creates good learning. If the plan is not reviewed, executed well and generates results less than anticipated, it’s not failure. You learned your process needs to change. Now it’s time to improve it.

When a good plan is executed poorly, there is no failure. You learned that one of your teams executed in a way that was different than your expectations. It’s time to learn why it went down as it did and why your expectations were the way they were. Learning on all fronts, failing on none.

Nothing good can come of using the f word, so don’t use it. Use “learn” instead. Don’t embrace failure, embrace learning. Don’t fail early and often, learn early and often. Don’t fail forward (whatever that is), just learn.

With failure there is fear of repercussion and a puckering on all fronts. With learning there is openness and opportunity. You choose the words, so choose wisely.

Image credit – IZATRINI.com

Is it novel?

Agree or not, companies think they have to grow to survive. (I don’t believe it.) For companies of all sizes and shapes, growth is the single most important forcing function. Is has tidal wave power, and whether you’re a surfer, sailor or power-boater, it’s important to respect it. More than that, when push comes to shove, it’s the only wave in town.

Agree or not, companies think they have to grow to survive. (I don’t believe it.) For companies of all sizes and shapes, growth is the single most important forcing function. Is has tidal wave power, and whether you’re a surfer, sailor or power-boater, it’s important to respect it. More than that, when push comes to shove, it’s the only wave in town.

Companies’ recipe for growth is simple: make more, sell more. And some keep it simpler: sell more.

The best growth: sell new products or provide new services to new customers; next best: sell new to the same customers; next next best: sell more of the same to the same customers. The last flavor is the easiest, right up until it isn’t. And once it isn’t, companies must come up with new things to sell. That works for a while, until it doesn’t. Then, and only then, after exhausting all other possibilities, companies must create real newness and try to sell it to strangers.

The model works well as long as everyone in the industry follows it. But when an up-start outsider enters the market back-to-front, the wheels fall off. When they develop useful newness before you and sell it to your customers (new customers for them), that’s not good. And that’s why it’s so important to start with different — right now.

To help your company do more work that’s different, start with an inventory of your novelty. Novel work is work that creates difference, and that difference can be defined only in comparison with the state-of-the-art (what is, or the baseline system). Start with a functional analysis of your state-of-the-art. Create a block diagram of your business model, your most successful product and the service that defines your brand. Take a look at your technology and new product development projects and flag the ones that will create things that aren’t on your three functional analyses. (Improvement projects, because they improve what is, cannot be flagged as novel.)

Put all your novelty on one page and decide if you like it. (No way around it, how you respond to the level and type of novelty in your quiver is a judgment call.) If you like what you see, keep going. If you don’t, stop some improvement projects and start some projects that create useful novelty. The stopping will not come easy. Existing projects have momentum and people have personal attachment to them. The only thing powerful enough to stop them is the all-powerful growth objective. If company leaders learn the existing projects won’t meet the growth objective, the tidal wave will sweep away some lesser projects to make room for new ones.

There will be great internal pressure to add projects without stopping some, but that won’t work. Everyone is fully booked and can’t deliver on additional projects even if you tell them to. If you’re not willing to stop projects, you’re better off staying the course and waiting until you finish one before you start a project to increase your novelty score.

Novelty is good because there’s more upside potential, and improvement is good because there’s more certainty. One is not better than the other. You need both.

In the end, you’re going to have to judge if you’re happy with what you’ve got. That’s a difficult task that no one can make easier for you. But it is possible to use your judgment better. If you can clearly call out what’s novel and what’s not, you’re on your way.

Image credit – s3aphotography (image cropped)

Put your success behind you.

The biggest blocker of company growth is your successful business model. And the more significant it’s historical success, the more it blocks.

Novelty meaningful to the customer is the life force of company growth. The easiest novelty to understand is novelty of product function. In a no-to-yes way, the old product couldn’t do it, but the new one can. And the amount of seconds it takes for the customer to notice (and in the case of meaningful novelty, appreciate) the novelty is in an indication of its significance. If it takes three months of using the product, rigorous data collection and a t-test, that’s not good. If the customer turns on the product and the novelty smashes him in the forehead like a sledgehammer, well, that’s better.

It’s difficult to create a product with meaningful novelty. Engineers know what they know, marketers know what they market, and the salesforce knows how to sell what they sell. And novelty cuts across their comfort. The technology is slightly different, the marketing message diverges a bit, and the sales argument must be modified. The novelty is driven by the product and the people respond accordingly. And, the new product builds on the old one so there’s familiarity.

Where injecting novelty into the product is a challenge, rubbing novelty on the business model provokes a level 5 pucker. Nothing has the stopping power of a proposed change to the business model. Novelty in the product is to novelty in the business model as lightning is to lightning bug – they share a word, but that’s it.

Novelty in the product is novelty of sheet metal, printed circuit boards and software. Novelty in the business model is novelty in how people do their work and novelty in personal relationships. Novelty in the product banal, novelty in the business model is personal.

No tools or best practices can loosen the pucker generated by novelty in the business model. The tired business model has been the backplane of success for longer than anyone can remember. The long-in-the-tooth model has worn deep ruts of success into the organization. Even the all-powerful Lean Startup methodology can’t save you.

The healing must start with an open discussion about the impermanence of all things, including the business model. The most enduring radioactive element has a half-life, and so does the venerable business model, even the most successful.

Where novelty in the product is technical, novelty in the business model is emotional. And that’s what makes it so powerful. Sprinkling the business model with novelty is scary at a deeply personal level – career jeopardy, mortgage insecurity and family volatility are primal drivers. But if you can push through, the rewards are magical.

Your business model has shaped you into an organization that’s optimized to do what it does. You can’t create new markets and sell to new products to new customers without changing your business model. Your business model may have been your secret sauce, but the world’s tastes have changed. It’s time to put your success behind you.

Image credit — MandaRose

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski