Archive for February, 2016

Patents are supposed to improve profitability.

Everyone likes patents, but few use them as a business tool.

Everyone likes patents, but few use them as a business tool.

Patents define rights assigned by governments to inventors (really, the companies they work for) where the assignee has the right to exclude others from practicing the concepts described in the patent claims. And patent rights are limited to the countries that grant patents. If you want to get patent rights in a country, you submit your request (application) and run their gauntlet. Patents are a country-by-country business.

Patents are expensive. Small companies struggle to justify the expense of filing a single patent and big companies struggle to justify the expense of their portfolio. All companies want to reduce patent costs.

The patent process starts with invention. Someone must go to the lab and invent something. The invention is documented by the inventor (invention disclosure) and the invention is scored by a cross-functional team to decide if it’s worthy of filing. If deemed worthy, a clearance search is done to see if it’s different from all other patents, all products offered for sale, and all the other literature in the public domain (research papers, publications). Then, then the patent attorneys work their expensive magic to draft a patent application and file it with the government of choice. And when the rejection arrives, the attorneys do some research, address the examiner’s concerns and submit the paperwork.

Once granted, the fun begins. The company must keep watch on the marketplace to make sure no one sells products that use the patented technology. It’s a costly, never-ending battle. If infringement is suspected, the attorneys exchange documents in a cease-and-desist jousting match. If there’s no resolution, it’s time to go to court where prosecution work turns up the burn rate to eleven.

To reduce costs, companies try to reduce the price they pay to outside law firms that draft their patents. It’s a race to the bottom where no one wins. Outside firms get paid less money per patent and the client gets patents that aren’t as good as they could be. It’s a best practice, but it’s not best. Treating patent work as a cost center isn’t right. Patents are a business tool that help companies make money.

Companies are in business to make money and they do that by selling products for more than the cost to make them. They set clear business objectives for growth and define the market-customers to fuel that growth. And the growth is powered by the magic engine of innovation. Innovation creates products/services that are novel, useful and successful and patents protect them. That’s what patents do best and that’s how companies should use them.

If you don’t have a lot of time and you want to understand a patent, read the claims. If you have less time, read the independent claims. Chris Brown, Ph.D.

Patents are all about claims. The claims define how the invention is different (novel) from what’s tin the public domain (prior art). And since innovation starts with different, patents fit nicely within the innovation framework. Instead of trying to reduce patent costs, companies should focus on better claims, because better claims means better patents. Here are some thoughts on what makes for good claims.

Patent claims should capture the novelty of the invention, but sometimes the words are wrong and the claims don’t cover the invention. And when that happens, the patent issues but it does not protect the invention – all the downside with none of the upside. The best way to make sure the claims cover the invention is for the inventor to review the claims before the patent is filed. This makes for a nice closed-loop process.

When a novel technology has the potential to provide useful benefit to a customer, engineers turn those technologies into prototypes and test them in the lab. Since engineers are minimum energy creatures and make prototypes for only the technologies that matter, if the patent claims cover the prototype, those are good claims.

When the prototype is developed into a product that is sold in the market and the novel technology covered by the claims is what makes the product successful, those are good claims.

If you were to remove the patented technology from the product and your customer would notice it instantly and become incensed, those are the best claims.

Instead of reducing the cost of patents, create processes to make sure the right claims are created. Instead of cutting corners, embed your patent attorneys in the technology development process to file patents on the most important, most viable technology. Instead of handing off invention disclosures to an isolated patent team, get them involved in the corporate planning process so they understand the business objectives and operating plans. Get your patent attorneys out in the field and let them talk to customers. That way they’ll know how to spot customer value and write good claims around it.

Patents are an important business tool and should be used that way. Patents should help your company make money. But patents aren’t the right solution to all problems. Patent work can be slow, expensive and uncertain. A more powerful and more certain approach is a strong investment in understanding the market, ritualistic technology development, solid commercialization and a relentless pursuit of speed. And the icing on the top – a slathering of good patent claims to protect the most important bits.

Image credit – Matthais Weinberger

You probably don’t have an organizational capability gap.

The organizational capability of a company defines its ability to get things done. If you can’t pull it off, you have an organizational capability problem, or so the traditional thinking goes.

The organizational capability of a company defines its ability to get things done. If you can’t pull it off, you have an organizational capability problem, or so the traditional thinking goes.

If you don’t have enough people to do the work, and the work is not new, that’s not a capability gap, that’s an organizational capacity gap. Capacity gaps are filled in straightforward ways. 1.) You can hire more people like the ones who do the work today and train them with the people you already have. Or for machines – buy more of the old machines you know and love. 2.) Map the work processes and design out the waste. Find the piles of paper or long queues and the bottleneck will be right in front. Figure out how to get more work through bottleneck. Professional tip – ignore everything but the bottleneck because fixing a non-bottleneck will only make you tired and sweaty and won’t increase throughput. 3.) Move people and machines from the work to create a larger shortfall. If no one complains, it wasn’t a problem and don’t fix it. If the complaints skyrocket, use the noise to justify the first or second option. And don’t let your ego get in the way – bigger teams aren’t better, they’re just bigger.

If your company systematically piles too work on everyone’s plate, you don’t have an organizational capability problem, you have a leadership problem.

If you’re asked to put together a future state organization and define its new capabilities, you don’t have an organizational capability gap. A capability gap exists only when there’s a business objective that must be satisfied, and a paper exercise to create a future state organization is not a business objective. Before starting the work, ask for the company’s growth objectives and an explanation of the new work your team will have to do to achieve those objectives. And ask how much money has been budgeted (and approved) for the future state organization and when you can make the first hire. This will reduce the urgency of the exercise, and may stop it altogether. And everyone will know there’s no “organizational capability gap.”

If you’re asked to put together a project plan (with timeline and budget) to create a new technology and present the plan to the CEO next week, you have an organizational capability gap. If there’s a shortfall in the company’s growth numbers and the VP of business development calls you at home and tells you to put together a plan to create a new market in a new country and present it to her tomorrow, you have an organizational capability gap. If the VP of sales takes you to a fancy restaurant and asks you to make a napkin sketch of your plan to sell the new product through a new channel, you have an organizational capability gap.

Real organizational capability gaps are rare. Unless there’s a change, there can be no organizational capability gap. There can be no gap without a new business deliverable, new technology, new partnership, new product, new market, or new channel. And without a timeline and an approved budget, I don’t know what you have, but you don’t have organizational capability gap.

Image credit – Jehane

Your Words Make All The Difference.

Sometimes people are unskillful with their words, and what they say can have multiple interpretations. But, though you don’t have control over their words, you do have control over how you interpret them. And the translation you choose makes all the difference. On the flipside, when you choose your words skillfully they can have a singular translation. And that, too, makes all the difference. Here are some examples.

Sometimes people are unskillful with their words, and what they say can have multiple interpretations. But, though you don’t have control over their words, you do have control over how you interpret them. And the translation you choose makes all the difference. On the flipside, when you choose your words skillfully they can have a singular translation. And that, too, makes all the difference. Here are some examples.

It can’t be done. Translations: 1) We’ve never tried it and we don’t know how to go about it. 2) We know you’ll not give us the time and the resources to do it right, and because of that, we won’t be successful. 3) Wow. I like that idea, but we’re already so overloaded. Do you think we can talk about that in the second half of the year?

We tried that but it didn’t work. Translations: 1) Twelve years ago someone who made a prototype and it worked pretty well. But, she wasn’t given the time to take it to the next level and the project was abandoned. 2) We all think that’s a wonderful idea and really want to work on it, but we’re too busy to think about that. If I come clean, will you give me the resources to do it right?

Why didn’t you follow the best practice? Translations: 1) I’m afraid of the uncertainty around this innovation work and I’ve heard best practices can reduce risk. 2) I don’t really know what I’m talking about, but this seems like a safe question to ask without tipping my hand. 3) I want to make a difference at the company, but I’ve never been part of a project with so much newness. Can you teach me?

That’s not how we do it. Translations: 1) I’ve always done it that way, and thinking about doing it differently scares me. 2) Though the process is clunky, we’ve been told to follow it. And I don’t want to get in trouble. 3) That sounds like a good idea, but I don’t have the time to think through the potential implications to our customers.

What are you working on? Translation: I’m interested in what you’re working on because I care about you.

Can I help you? Translation: You’ve helped me in the past and I see you’re in a tough situation. I care about you. What can I do to help?

Good job. Translation: I want to positively reinforce your good work in front of everyone because, well, you did good work.

That’s a good idea. Translation: I think highly of you, I like that you stuck out your neck, and I hope you do it regularly.

I need help. Translation: I know you are highly capable and I trust you. I’m in a tight spot here. Can you help me?

Thank you. Translation: You were helpful and I appreciate it. Thank you.

How you choose your words and how you choose to assign meaning to others’ words make all the difference. Choose skillfully.

image credit — woodleywonderworks

You don’t find the next new thing, it finds you.

Doing something new is harder than it looks.

Doing something new is harder than it looks.

The first step to doing new is to realize you have no interest in doing what was done last time. Profitable or not, the same old recipe just doesn’t do it for you. You don’t have to know why you don’t want to replay the tape, you just have to know you don’t want to. So don’t.

But it’s not enough to know what you don’t want to do, you’ve got to know what you do want to do. To figure that out, you’ve got to stop doing. The focused, churning mind isn’t your friend here because it thinks of ideas that are too closely related to what it knows. This is the job for the idle mind. The idle mind has nothing to focus on, so it doesn’t. It runs in the background imagining the impossible and considering the absurd. And since it runs without your knowledge, you can’t get in its way. So do nothing. Turn off your electronics and sit. Feel uncomfortable. Give your mind no place to go so it can go where it wants. Read a biography about an important historical figure. Travel to their century so while you’re visiting your subconscious can figure out what to do.

You don’t figure out what’s next. What’s next finds you while you’re not looking for it. And the best way to do that is to do nothing.

Doing nothing is a lot of work. And it’s difficult to do. My advice – start with 15 minutes of nothing. Anything more is too much. Take your mobile phone out of your pocket, put it on your desk (or throw it at the floor and stomp on it) and walk to a quiet place and sit. Close your eyes, sit and watch. You’ll see your monkey mind search for the next big thing and not find it. Then you’ll see it think about something that scares you and you’ll get scared. Then you’ll see it think about an old argument and you’ll jump back into it and relive it. Then, after a while, you’ll realize you’re not watching, you’re reliving. Then you’ll see your mind try again in vain to find the next thing to do. And after 15 minutes of this nonsense, you’re done with your first session of nothing.

Repeat this process over 5 days and a good idea will find you. You may be sleeping, showering, eating or reading, but no worries, it will find you. Something will click and you’ll put together two things that aren’t meant to be together but, once together, make a lot of sense – like a strange Ben and Jerry’s flavor you taste for the first time and eat the whole pint.

The new idea isn’t the new thing itself, it’s the first step toward finding the next thing to do. But, you’ve started wandering down a crazy new path that’s no longer crazy, and you’re on your way.

Resume your daily 15 minute sessions of nothing and, in between, mix in some small experiments to test, refine or invalidate your next new thing. Repeat, as needed.

And don’t stop until what you’re looking for finds you.

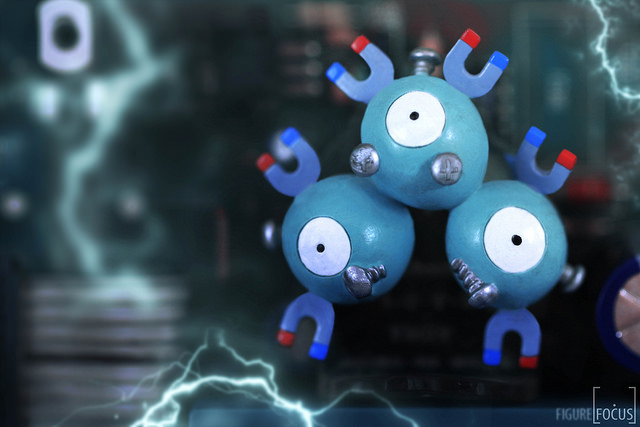

Image credit – Figure Focus.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski