Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

Function first, no exceptions.

Before a design can be accused of having too much material and labor costs, it must be able to meet its functional specifications. Before that is accomplished, it’s likely there’s not enough material and labor in the design and more must be added to meet the functional specifications. In that way, it likely doesn’t cost enough. If the cost is right but the design doesn’t work, you don’t have a viable offering.

Before a design can be accused of having too much material and labor costs, it must be able to meet its functional specifications. Before that is accomplished, it’s likely there’s not enough material and labor in the design and more must be added to meet the functional specifications. In that way, it likely doesn’t cost enough. If the cost is right but the design doesn’t work, you don’t have a viable offering.

Before the low-cost manufacturing process can be chosen, the design must be able to do what customers need it to do. If the design does not yet meet its functional specification, it will change and evolve until it can. And once that is accomplished, low-cost manufacturing processes can be selected that fit with the design. Sure, the design might be able to be subtly adapted to fit the manufacturing process, but only as much as it preserves the design’s ability to meet its functional requirements. If you have a low-cost manufacturing process but the design doesn’t meet the specifications, you don’t have anything to sell.

Before a product can function robustly over a wide range of operating conditions, the prototype design must be able to meet the functional requirements at nominal operating conditions. If you’re trying to improve robustness before it has worked the first time, your work is out of sequence.

Before you can predict when the project will be completed, the design must be able to meet its functional requirements. Before that, there’s no way to predict when the product will launch. If you advertise the project completion date before the design is able to meet the functional requirements, you’re guessing on the date.

When your existing customers buy an upgrade package, it’s because the upgrade functions better. If the upgrade didn’t work better, customers wouldn’t buy it.

When your existing customers replace the old product they bought from you with the new one you just launched, it’s because the new one works better. If the new one didn’t work better, customers wouldn’t buy it.

Function first, no exceptions.

Image credit — Mrs Airwolfhound

How To Finish Projects

Finishing a project is usually associated with completing all the deliverables. But in the real world there are other flavors of finishing that come when there is no reason or ability to complete all the deliverables or completing them will take too long.

Finishing a project is usually associated with completing all the deliverables. But in the real world there are other flavors of finishing that come when there is no reason or ability to complete all the deliverables or completing them will take too long.

Everyone’s favorite flavor of finishing is when all the deliverables are delivered and sales of the new product are more than anticipated. Finishing this way is good for your career. Finish this way if you can.

When most of the deliverables are met, but some of them aren’t met at the levels defined by the specification, the specification can be reduced to match the actual performance and the project can be finished. This is the right thing to do when the shortfall against the specification is minor and the product will still be well received by customers. In this case, it makes no sense to hold up the launch for a minor shortfall. There is no shame here. It’s time to finish and make money.

After working on the project for longer than planned and the deliverables aren’t met, it’s time to finish the project by stopping it. Though this type of finishing is emotionally difficult, finishing by stopping is far better than continuing to spend resources on a project that will likely never amount to anything. Think opportunity cost. If allocating resources to the project won’t translate into customer value and cash, it’s better to finish now so you can allocate the resources to a project that has a better chance of delivering value to you and your customers.

Before a project is started in earnest and the business case doesn’t make sense, or the commercial risk is too high, or the technical risk is too significant, or it’s understaffed, finish the project by not starting it. This is probably the most important type of finishing you can do. Again, think of opportunity cost. By finishing early (before starting) resources can start a new project almost immediately and resources were prevented from working on a project that wasn’t going to deliver value.

Just as we choose the right way to start projects and the right way to run them, we must choose the right way to finish them.

Image credit — majiedqasem

The Three Ts of Empowerment

If you give a person the tools, time, and training, you’ve empowered them. They know what to do, they have supporting materials, and they have the permission to spend the time they need to get it done.

If you give a person the tools, time, and training, you’ve empowered them. They know what to do, they have supporting materials, and they have the permission to spend the time they need to get it done.

If you give a person the tools and the time but not the training, they will struggle to figure out the tools but they’ll likely get there in the end. It won’t be all that efficient, but because you’ve given them the time they’ll be able to figure out the tools and get it done.

If you give a person the time but not the tools or the training, they’ll go on a random walk and make no progress. Yes, you’ve given them the time, but you’ve given them no real support or guidance. They’ll likely become tired and frustrated and you’ll have allocated their time yet made no progress.

If you give a person the tools and training but not the time, you’ve demoralized them. They have new skills and new tools and want to use them, but they’re too busy doing their day job. This is the opposite of empowerment.

If you’re not willing to give people the time to do new work, don’t bother providing new tools, and don’t bother training them. Stay the course and accept things as they are. Otherwise, you’ll disempower your best people.

But if you want to empower people, give them all three – tools, time, and training.

Image credit — Paul Balfe

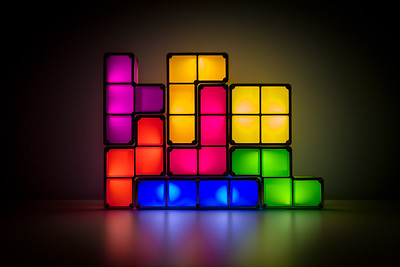

Playing Tetris With Your Project Portfolio

When planning the projects for next year, how do you decide which projects are a go and which are a no? One straightforward way is to say yes to projects when there are resources lined up to get them done and no to all others. Sure, the projects must have a good return on investment but we’re pretty good at that part. But we’re not good at saying no to projects based on real resource constraints – our people and our budgets.

When planning the projects for next year, how do you decide which projects are a go and which are a no? One straightforward way is to say yes to projects when there are resources lined up to get them done and no to all others. Sure, the projects must have a good return on investment but we’re pretty good at that part. But we’re not good at saying no to projects based on real resource constraints – our people and our budgets.

It’s likely your big projects are well-defined and well-staffed. The problem with these projects is usually the project timeline is disrespectful of the work content and the timeline is overly optimistic. If the project timeline is shorter than that of a previously completed project of a similar flavor, with a similar level of novelty and similar resource loading, the timeline is overly optimistic and the project will be late.

Project delays in the big projects block shared resources from moving onto other projects within the appropriate time window which cascades delays into those other projects. And the project resources themselves must stay on the big projects longer than planned (we knew this would happen even before the project started) which blocks the next project from starting on time and generates a second set of delays that rumble through the project portfolio. But the big projects aren’t the worst delay-generating culprits.

The corporate initiatives and infrastructure projects are usually well-staffed with centralized resources but these projects require significant work from the business units and is an incremental demand for them. And the only place the business units can get the resources is to pull them off the (too many) big projects they’ve already committed to. And remember, the timelines for those projects are overly optimistic. The big projects that were already late before the corporate initiatives and infrastructure projects are slathered on top of them are now later.

Then there are small projects that don’t look like they’ll take long to complete, but they do. And though the project plan does not call for support resources (hey, this is a small project you know), support resources are needed. These small projects drain resources from the big projects and the support resources they need. Delay on delay on delay.

Coming out of the planning process, all teams are over-booked with too many projects, too few resources, and timelines that are too short. And then the real fun begins.

Over the course of the year, new projects arise and are started even though there are already too few resources to deliver on the existing projects. Here’s a rule no one follows: If the teams are fully-loaded, new projects cannot start before old ones finish.

It makes less than no sense to start projects when resources are already triple-double booked on existing projects. This behavior has all the downside of starting a project (consumption of resources) with none of the upside (progress). And there’s another significant downside that most don’t see. The inappropriate “starting” of the new project allows the company to tell itself that progress is being made when it isn’t. All that happens is existing projects are further starved for resources and the slow pace of progress is slowed further.

It’s bad form to play Tetris with your project portfolio.

Running too many projects in parallel is not faster. In fact, it’s far slower than matching the projects to the resources on-hand to do them. It’s essential to keep in mind that there is no partial credit for starting a project. There is 100% credit for finishing a project and 0% credit for starting and running a project.

With projects, there are two simple rules. 1) Limit the number of projects by the available resources. 2) Finish a project before starting one.

Image credit – gerlos

When you say yes to one thing, you say no to another.

Life can get busy and complicated, with too many demands on our time and too little time to get everything done. But why do we accept all the “demands” and why do we think we have to get everything done? If it’s not the most important thing, isn’t a “demand for our time” something less than a demand? And if some things are not all that important, doesn’t it say we don’t have to do everything?

Life can get busy and complicated, with too many demands on our time and too little time to get everything done. But why do we accept all the “demands” and why do we think we have to get everything done? If it’s not the most important thing, isn’t a “demand for our time” something less than a demand? And if some things are not all that important, doesn’t it say we don’t have to do everything?

When life gets busy, it’s difficult to remember it’s our right to choose which things are important enough to take on and which are not. Yes, there are negative consequences of saying no to things, but there are also negative consequences of saying yes. How might we remember the negative consequences of yes?

When you say to yes to one thing, you say no to the opportunity to do something else. Though real, this opportunity cost is mostly invisible. And that’s the problem. If your day is 100% full of meetings, there is no opportunity for you to do something that’s not on your calendar. And in that moment, it’s easy to see the opportunity cost of your previous decisions, but that doesn’t do you any good because the time to see the opportunity cost was when you had the choice between yes and no.

If you say yes because you are worried about what people will think if you say no, doesn’t that say what people think about you is important to you? If you say yes because your physical health will improve (exercise), doesn’t that say your health is important to you? If you say yes to doing the work of two people, doesn’t it say spending time with your family is less important?

Here’s a proposed system to help you. Open your work calendar and move one month into the future. Create a one-hour recurring meeting with yourself. You just created a timeslot where you said no in the future to unimportant things and said yes in the future to important things. Now, make a list of three important things you want to do during those times. And after one month of this, create a second one-hour recurring meeting with yourself. Now you have two hours per week where you can prioritize things that are important to you. Repeat this process until you have allocated four hours per week to do the most important things. You and stop at four hours or keep going. You’ll know when you get the balance right.

And for Saturday and Sunday, book a meeting with yourself where you will do something enjoyable. You can certainly invite family and/or friends, but it the activity must be for pure enjoyment. You can start small with a one-hour event on Saturday and another on Sunday. And, over the weeks, you can increase the number and duration of the meetings.

Saying yes in the future to something important is a skillful way to say no in the future to something less important. And as you use the system, you will become more aware of the opportunity cost that comes from saying yes.

Image credit – Gilles Gonthier

If you want to change things, do a demo.

When you demo something new, you make the technology real. No longer can they say – that’s not possible.

When you demo something new, you make the technology real. No longer can they say – that’s not possible.

When you demo something new, you help people see what it is and what it isn’t. And that brings clarity.

When you demo something new, people take sides. And that says a lot about them.

When you demo something new, be prepared to demo it again. It takes time for people to internalize new concepts.

When someone asks you to repeat the demo so others can see it, it’s a sign there’s something interesting about the demo. Repeat it.

When someone calls out fault with a minor element of the demo, they also reinforce the strength of the main elements.

When you demo something new and it works perfectly, you should have demo’d it sooner.

When the demo works perfectly, you’re not trying hard enough.

When you demo something new, there is no way to predict the action items spawned by the demo. In fact, the reason to do the demo is to learn the next action items.

When you demo something new, make the demo short so the conversation can be long.

When you demo something new, shut your mouth and let the demo do the talking.

When you demo something new, keep track of the questions that arise. Those questions will inform the next demo.

When you demo something new and it’s misunderstood, congratulations. You’ve helped the audience loosen their thinking.

If you want to change people’s thinking, do a demo.

Image credit – Ralf Steinberger

Overcoming Not Invented Here (NIH), The Most Powerful Blocker of Innovation

When new ideas come from the outside, they are dismissed out of hand. The technical term for this behavior is Not Invented Here (NIH). Because it was not invented by the party with official responsibility, that party stomps it into dust. But NIH doesn’t stomp in public; it stomps in mysterious ways.

When new ideas come from the outside, they are dismissed out of hand. The technical term for this behavior is Not Invented Here (NIH). Because it was not invented by the party with official responsibility, that party stomps it into dust. But NIH doesn’t stomp in public; it stomps in mysterious ways.

Wow! That’s a great idea! Then, mysteriously, no progress is made and it dies a slow death.

That’s cool! Then there’s a really good reason why it can’t be worked.

That’s interesting! Then that morphs into the kiss of death.

We never thought of that. But it won’t scale.

That’s novel! But no one is asking for it.

That’s terribly exciting! We’ll study it into submission.

That’s incredibly different! And likely too different.

When the company’s novel ideas die on the vine, they likely die at the hands of NIH. If you can’t understand why a novel idea never made it out of the lab, investigate the crime scene and you may find NIH’s fingerprints. If customers liked the new idea yet it went nowhere, it could be NIH was behind the crime. If it makes sense, but it doesn’t make progress, NIH is the prime suspect.

If a team is not receptive to novel ideas from the outside, it’s because they consider their own ideas sufficiently good to meet their goals. Things are going well and there’s no reason to adopt new ideas from the outside. And buried in this description are the two ways to overcome NIH.

The fastest way to overcome NIH is to help a new idea transition from an idea conceived by someone outside the team to an idea created by someone inside the team. Here’s how that goes. The idea is first demonstrated by the external team in the form of a functional prototype. This first step aims to help the internal team understand the new idea. Then, the first waiting period is endured where nothing happens. After the waiting period, a somewhat different functional prototype is created by the external team and shown to the internal team. The objective is to help the internal team understand the new idea a little better. Then, the second waiting period is endured where nothing happens. Then, a third functional prototype is created and shown to the internal team. This time, shortcomings are called out by the external team that can only be addressed by the internal team. Then, the last waiting period is endured. Then, after the third waiting period, the internal team addresses the shortcomings and makes the idea their own. NIH is dead, and it’s off to the races.

The second fastest way to overcome NIH is to wait for the internal team to transition to a team that is receptive to new ideas initiated outside the team. The only way for a team to make the transition is for them to realize that their internal ideas are insufficient to meet their objectives. This can only come after their internal ideas are shown to be inadequate multiple times. Only after exhausting all other possibilities, will a team consider ideas generated from outside the team.

When the external team recognizes the internal team is out of ideas, they demonstrate a functional prototype to the internal team. And they do it in an “informational” way, meaning the prototype is investigatory in nature and not intended to become the seed of the internal team’s next generation platform. And as it turns out, it’s only a strange coincidence that the functional prototype is precisely what the internal team needs to fuel the next-generation platform. And the prototype is not fully wrung out. And as it turns out, the parts that need to be wrung out are exactly what the external team knows how to do. And when the internal team needs expertise from the external team to address the novel elements, as it turns out the external team conveniently has the time to help out.

Not Invented Here (NIH) is real. And it’s a powerful force. And it can be overcome. And when it is overcome, the results are spectacular.

Image credit — Becky Mastubara

Show Them What’s Possible

When you want to figure out what’s next, show customers what’s possible. This is much different than asking them what they want. So, don’t do that. Instead, show them a physical prototype or a one-page sales tool that explains the value they would realize.

When you want to figure out what’s next, show customers what’s possible. This is much different than asking them what they want. So, don’t do that. Instead, show them a physical prototype or a one-page sales tool that explains the value they would realize.

When they see what’s possible, the world changes for them. They see their work from a new perspective. They see how the unchangeable can change. They see some impossibilities as likely. They see old constraints as new design space. They see the implications of what’s possible from their unique context. And they’re the only ones that can see it. And that’s one of the main points of showing them what’s possible – for YOU to see the implications of what’s possible from their perspective. And the second point is to hear from them what you should have shown them, how you missed the mark, and what you should show them next time.

When you show customers what’s possible, that’s not where things end. It’s where things start.

When you show customers what’s possible, it’s an invitation for them to tell you what it means to them. And it’s also an invitation for you to listen. But listening can be challenging because your context is different than theirs. And because they tell you what they think from their perspective, they cannot be wrong. They might be the wrong customer, or you might have a wrong understanding of their response, but how they see it cannot be wrong. And this can be difficult for the team to embrace.

What you do after learning from the customer is up to you. But there’s one truism – what you do next will be different because of their feedback. I am not saying you should do what they say or build what they ask for. But I think you’ll be money ahead if your path forward is informed by what you learn from the customers.

Image credit — Alexander Henning Drachmann

Start, Stop, Continue Gone Bad

Stop, Start, Continue is a powerful, straightforward way to manage things.

Stop, Start, Continue is a powerful, straightforward way to manage things.

If it’s not working, Stop.

If it’s working well, Continue.

If there’s a big opportunity to grow, Start.

Sounds pretty simple, but it’s often executed poorly.

The most dangerous variant of Stop, Start, Continue is Start, Start, Continue. Regardless of how well projects are doing, they Continue. The market has changed but the product hasn’t launched yet, Continue the project. Though the technical risk is increasing instead of decreasing, keep your mouth shut and Continue the project. Though resources have moved to different projects (that have recently started), Continue the project and pretend progress is being made. And though Continue is a big problem, Starting is a bigger one.

With Start, Start, Continue, the company’s eyes are too big for their stomach. Because there is no mechanism to limit the start of new projects based on the available resources (people, tools, infrastructure), projects start without the resources needed to get them done. In the short term, there’s a celebration because an important new project has started. But a month later, everyone on the project team knows the project is doomed because the project is largely unstaffed. And because of the tight lips, no one in company leadership knows there’s a problem. The telltale signs of Start, Start, Continue are long projects (insufficient resources) and a lack of Finishing (too many projects and too little focus).

There is a little-known process that can overpower Start, Start, Continue. It’s called Stop, Stop, Stop. It’s simple and powerful.

With Stop, Stop, Stop, stalled projects are stopped and resources are freed up to accelerate the best remaining projects. Think of it as moving from Continue existing projects to Accelerate the most important projects. And with Stop, Stop, Stop, there is no starting. None. There is only stopping, at least to start. Pet projects are stopped. Long-in-the-tooth projects are stopped. Irrelevant projects are stopped. And even good projects are stopped to allow great projects to Start.

With Stop, Stop, Stop, at least two projects must stop before a new project can start. And it’s better to stop three.

The result of Stop, Stop, Stop is a glut of freed-up resources that can be applied to amazing new projects. And because the resources are unallocated and ready to go, those new projects can be fully staffed and can make progress quickly. And because there are now fewer projects overall, the shared resources can respond more quickly for double acceleration. And with fewer projects, there are fewer resource collisions among projects and fewer slowdowns. Triple acceleration and a lighter project management burden.

If your projects are moving too slowly, use Stop, Stop, Stop to stop the worst projects. If you have too many projects and too few resources, Stop, Stop, Stop can set you free. If you want to Start an amazing new project, use Stop, Stop, Stop to free up the resources to make it happen.

Before you Start, Stop. And before you Continue, Stop. And instead of pretending to Stop or talking about Stopping, Stop.

How To Grow Talent

Show them how the work is done.

Show them how the work is done.

Ask them what they saw.

Praise them for what they recognized and describe what they didn’t.

Repeat

Explain how the work is done.

You do work, and they watch. Then switch places.

Ask them what they felt and what questions they have.

Praise them for their openness and answer their questions.

Repeat.

Ask them how the work should be done and listen.

Praise them for their insights and suggest alternative approaches for consideration.

Choose the work together. They do the work. You check in as needed.

Ask them how they felt while doing the work. Ask if they have questions.

Praise them for sharing, validate their feelings, and answer their questions.

Repeat.

Ask them to do the work.

They choose the approach and do the work. You do something else, but stay close.

If they ask questions, answer them.

Check in with them after the work is done, but they own the agenda.

Repeat

Ask them what work should be done next and listen.

Acknowledge their discomfort. Explain that it’s supposed to feel like that.

They choose the work, they choose the approach, and you stay away.

If they ask questions, answer with more questions. They can work it out on their own.

Check in with them after the work is done, but make it a social visit. That’s how pros treat other pros.

Image credit – skyseeker

The Best Way To Make Projects Go Faster

When there are too many projects, all the projects move too slowly.

When there are too many projects, all the projects move too slowly.

When there are too many projects, adding resources doesn’t help much and may make things worse.

To speed up the important projects, stop the less important projects. There’s no better way.

When there are too many projects, stopping comes before starting.

All projects are important, it’s just that some are more important than others. Stop the lesser ones.

When someone says all projects are equally important, they don’t understand projects.

If all projects are equally important, then they are also equally unimportant and it does not matter which projects are stopped. This twist of thinking can help people choose the right projects to stop.

When there are too many projects, stop two before starting another.

Finishing a project is the best way to stop a project, but that takes too long. Stop projects in their tracks.

There is no partial credit for a project that is 80% complete and blocking other projects. It’s okay to stop the project so others can finish.

Queueing theory says wait times increase dramatically when utilization of shared resources reaches 85%. The math says projects should be stopped well before shared resources are fully booked.

If you want to go faster, stop the lesser projects.

Image credit – Rodrigo Olivera

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski