Posts Tagged ‘Competitiveness’

Would you rather have too many projects or too many resources?

When you have more projects than people, you have far more activity but far less progress.

When you have more projects than people, you have far more activity but far less progress.

Pro Tip: Activity doesn’t pay the bills. Progress does.

Would you rather make lightning progress on two projects or tortoise progress on four? I prefer lightning.

But isn’t four projects better than two? It is, if you get compensated for the number of active projects. But it’s not, if you get compensated for finishing projects.

Pro tip: There’s no partial credit for a project that’s less than 100% done.

But how to protect your resources from four projects when you have the resources to deliver on two? This is not a complicated answer: block the extra project from entering the pipeline until you finish one.

Pro Tip: Finish one before you start one, not the other way around.

But what about the efficiency that comes from shared resources that can be spread over four projects? Don Reintertsen would say “Shared resources create waiting and waiting is the enemy.” I agree with Don, but I think his language is too reserved. I say “If you’re focused on the efficiency that comes from shared resources, you don’t know what you’re doing.”

Pro Tip: Waiting kills progress. Don’t do it.

Here’s a process to consider.

- Define the resources you have on hand to work on projects.

- Choose the most important project and fully staff the project. If the project is fully staffed, start the project.

- Define the remaining unallocated resources.

- Choose the next most important project and fully staff the project. If the project is fully staffed, start the project. If the project is not fully staffed, don’t start a project until you finish one, or you can hire the incremental resources to fully staff a project.

- Repeat.

Image credit – KIUKO (Elephant Tortoise)

Do you have what it takes?

When there’s no light, no one can see.

When there’s no light, no one can see.

When no one can see, what do you do?

Can you be a source of light?

Do you care enough to do that?

When there’s too much input, focus is difficult.

When there’s a shortfall of focus, what do you do?

Can you dampen things and bring focus?

Do you have the emotional energy for that?

When there’s too much emotional stress, people become scattered.

When scattering comes, what do you do?

Can you pull people together?

Do you take responsibility and do that?

When the old recipe no longer works, people pucker.

When there is puckering, what do you do?

Can you recognize the pucker and plot a new course?

Do you bring the energy for that?

When there is support and guidance, people do great work.

When they did great work, did you play a role?

When they did great work, did you tell them?

Do you have the mojo to do it again?

When there is air cover and protection, people take risks.

When they took a risk, did you create the causes and conditions?

When they took a risk, did you praise them in public?

Do you have what it takes to praise in public?

When there is a teacher and time to learn, everything gets better.

When they learned, were you the teacher?

When they learned, did you create the opportunity for them to demonstrate their learning?

Do you have what it takes to teach and create the causes and conditions for learning to come more easily?

Image credit — Darren Flinders, Flamborough Lighthouse

Projects generate progress.

Companies make progress through projects.

Companies make progress through projects.

Projects have objectives that are defined by the company’s growth or improvement objectives.

Projects have quantifiable goals that are, hopefully, time-bound.

Projects require resources, and those resources limit the number of projects that are completed.

Projects are run with the resources allocated, not with the resources we want to allocate.

Projects have timelines that are governed by the work content, novelty, and resources.

Project timelines cannot violate the governing constraints of work content, novelty, and resources.

Projects have project managers, or they’re not projects.

Projects can be accelerated by eliminating waiting. To find the waiting, look for the work queued up in front of the bottleneck resources. Those resources are usually resources that support multiple projects (shared resources). When it comes to waiting, shared resources are almost always the culprit.

Projects have a critical path. A one-day delay (waiting) on the critical path delays project completion by a day. That’s how you know it’s the critical path.

If you don’t know the project’s critical path, you don’t know much.

When it comes to projects, effectiveness is far more important than efficiency, yet we fixate on efficiency. Would you rather run the wrong project efficiently (ineffective) or run the right project inefficiently (effective)?

Regardless of the business you’re in, it’s all about the projects.

Image credit — State Library of South Australia

Overcoming Your Success

Success locks in current practice.

Success locks in current practice.

May you have the blessing of declining revenues to see what must change.

Year-on-year growth hides inefficiencies.

May you have one bad year to help you see those inefficiencies.

Past success blinds us to the onset of decline.

May you have brave heretics to sound the alarm early in the decline.

A strong track record of growth prevents new ideas from seeing the light of day.

May you allocate revenue from that growth to bring the next-generation offering to life.

High market share creates intellectual inertia and stagnation.

May you have the luxury of strong competitors that get stronger every year.

A history of unassailable technical advantage breeds competence-induced failure.

May you have the courage to obsolete your best work.

A strong focus on process, combined with remarkable success, extends standard work beyond its useful life.

May you recognize that commercial conditions have changed, and it’s time to dismantle the very thing that generated your success.

Image credit — Thomas_H_foto

Decisions, Decisions, Decisions

If a decision can be unmade, it’s okay to make it quickly.

If a decision can be unmade, it’s okay to make it quickly.

Delaying a decision is a decision.

When a decision remains unmade, there’s a reason. However, that reason is often unspoken.

The effort to make the right decision is proportional to the consequences of getting it wrong.

Decisions are sometimes made without the non-deciders realizing that they were made.

Trouble arises when the decision maker is not the customer of the consequences.

Decisions are made slowly when people are afraid to make them.

When you don’t know a decision was made, you’ll continue to behave as if it wasn’t.

If five people are responsible for the decision, who is responsible for the decision?

Even if you are unaware that a decision was made, you’ll likely be expected to behave as if you knew it was.

If no decisions will be made at the meeting, don’t go. Just read the minutes.

Documenting decisions is not standard work, but I think it should be.

Decisions can be made, not made, unmade, re-made, and re-unmade.

Decisions aren’t decisions until behavior aligns with them.

When a decision is yet to be made, you can influence the decision by behaving as if it was made in your favor.

If you wait long enough, the decision will make itself.

Image credit — yawning hunter

996 or Bust

996 is all the rage. You work 9 am to 9 pm, 6 days a week. Startups are doing it. Might non-startups start doing it?

996 is all the rage. You work 9 am to 9 pm, 6 days a week. Startups are doing it. Might non-startups start doing it?

Productivity is important and competition is severe. And I’m all for working hard, but I don’t think the 996 schedule is the most effective way to achieve productivity goals, at least not for all jobs.

My decision-making capabilities diminish when I am tired, and I would be tired if I worked a 996 schedule. My interpersonal and organizational effectiveness would suffer if I worked 996. My planning skills would degrade if I worked 996. My family life would suffer if I worked 996. And my physical and mental health would degrade..

In my work, I make many decisions, I create conditions for teams and organizations to do new work, and I contemplate the future and figure out what to do next. Maybe I should be able to do this work well with a 996 schedule. But I know myself, and I know I would be far less effective working 996. Maybe my work is uniquely unfit for 996? Maybe I am uniquely unfit for 996?

Some questions for you:

- How many hours can you concentrate in one day?

- How about the second day?

- If you worked a 996 schedule, would you get more done?

- How many weeks could you work 996 before the wheels fall off?

The startup pace is rapid. Progress must be made before the money runs out. At these early stages, when a company’s existence depends on hitting the super agressive timelines, I think 996 is especially attractive to startup companies The potential financial upside is large which may make for a fair trade – more hours for the chance of outsized compensation.

But what if an established company sets extremely tight timelines and offers remarkable compensation if those timelines are met? Does 996 become viable? What if an established company sets startup-like timelines but without added compensation? Would 996 be viable in that case?

Some countries and regions work a 996 schedule as a matter of course – no limited to startups and (likely) no special compensation. And it seems to work for them, at least from the outside. And 996 may be an important supporting element of their impressively low costs, high quality, and speed.

If those countries amd regions can sustain their 996 culture, and I think they will, it will create pressure on other countries to adopt a similar approach to avoid falling further behind.

I’m unsure what broad adoption of 996 would mean for the world.

Image credit — Evan

When Your Plans Must Change….

To do new things, you’ve got to stop old things.

To do new things, you’ve got to stop old things.

If you don’t stop old things, you can’t start new things.

Resources limit the work that can be done.

If you have more work than resources, you won’t be able to complete everything.

Spread your resources across fewer projects, and you’ll accomplish more.

If you run more projects, you’ll get fewer done. Resource density matters.

For new behavior to start, old behavior must stop.

If you don’t stop old behavior, you can’t start new behavior.

When your standard work no longer works, it becomes non-standard work.

When it’s time for new work, non-standard work becomes standard work.

To get more done, improve efficiency.

To get the right work done, improve effectiveness.

New behavior requires a forcing function.

No forcing function, no change.

Things change at the speed of trust.

No trust, no change.

Transformational change isn’t a thing.

Evolutionary change is a thing.

Starting new projects is easy.

Finishing new projects requires stopping/finishing old ones, which is difficult.

Creating a start-doing list is common.

Creating a stop-doing list is unheard of.

Image credit — Demetri Dourambeis

Getting To Know Your Projects

Good new product development projects deliver value to customers. Bad ones create value for your company, not for customers. Can you discern between custom value and company value? What do you do when there’s an abundance of company value and a shortfall of customer value? Do you run the project anyway or pull the emergency brake as soon as possible?

Customers decide if the new product has value. That’s a rule. No one likes that rule, but it’s still a rule. The loudest voice doesn’t decide; it only drowns out the customer’s voice.

Having too many projects is worse than having too few. With too few, you finish projects quickly because shared resources are not overutilized. With too many, shared resources are overbooked, their service times blossom, and projects are late. Would you rather start two projects and finish two or start seven and finish none? That’s how it goes with projects.

Three enemies of new product development: waiting, waiting, waiting. Waiting that extends the critical path is the worst flavor of all. Can you tell when the waiting is on the critical path? If you calculate the cost of delay, it’s possible to spend money to eliminate waiting that’s on the critical path and make more money for your company. H/T to Don Rienertsen.

For projects, effectiveness is more important than efficiency. Yes, you read that correctly. Would you rather efficiently run the wrong project (low effectiveness) or run the right project inefficiently? Do you spend more mental energy on efficiency or effectiveness? (You don’t have to say your answer out loud.)

I think post-mortems of projects have no value. The next project will be different, and the learning will not be applicable or forgotten altogether. However, I think pre-mortems are powerful and can improve the effectiveness of a project BEFORE it is started. I suggest you try it on your next project.

Strategy is realized through projects. Projects generate growth. Cost savings come to life through projects. I think building a deeper understanding of your projects is the most important thing you can do.

Image credit — Mike Keeling (one too many head on collisions)

Solving The Wrong Problem

The CEO doesn’t decide if it’s good enough. The VP of Marketing doesn’t decide if it’s good enough. The VP of Engineering doesn’t decide if it’s good enough. The customer decides if it’s good enough.

The CEO doesn’t decide if it’s good enough. The VP of Marketing doesn’t decide if it’s good enough. The VP of Engineering doesn’t decide if it’s good enough. The customer decides if it’s good enough.

If the product isn’t selling, the price may be okay, but the performance may not be good. In this case, it’s time to add some sizzle. And who decides if the sizzle is sufficient? You guessed it – the customer. And if you add the sizzle and they buy more, the sizzle was the problem. If they don’t buy more, it wasn’t the sizzle.

If the product isn’t selling, the performance may be okay, but the price may be too high. In this case, it’s time to pull some cost out of the product and reduce the price. Maybe a better way is to test a lower price with customers. If they buy more, it’s worth doing the work to pull out the cost. If they don’t buy at the lower price, the price isn’t the problem. You still have some work to do.

If the product isn’t selling, both the performance and the price may be the problem. It’s time to add some sizzle and lower the price. But there’s no need to do the work until you test the hypothesis. Make a one-page sales tool with the new sizzle and price. If they like it, make it so. If they don’t like it, make another sales tool with some different sizzle and a different price. Repeat the process until the customer likes the new offering. Then, make it so.

If the product isn’t selling, it’s possible the sales channel isn’t making enough money when they sell your product. To test this, go on several sales calls with them. If they are unwilling to bring you on the sales calls, it’s a good sign that there’s not enough money in it for them. There are three ways to move forward. Reduce the price to the channel partner. If they sell more, you’re off to the races if, of course, there is enough margin in the product to support the reduced price. Make it easier for them to sell your product so they spend less time and effort and make more profit. Sell through a different channel.

When your product isn’t selling, figure out why it isn’t selling. And because there are many possible reasons your product isn’t selling, it’s best to create a hypothesis and test it. Your job is not to solve the problem; rather, your job is to figure out what the problem is and to decide whether it’s worth solving.

If you create a one-page sales tool with a lower price and customers still don’t want to buy it, don’t bother to design out the cost or reduce the price. If you create a one-page sales tool with a new DVP and the customers still don’t want to buy it, don’t do the work to develop that new DVP. If you test a reduced price to the channel and they sell a few more systems, don’t reduce the price because it’s not worth it.

Once you have objective evidence that you know what the problem is and it’s worth solving, do the work to solve it and implement the solution. If you don’t have objective evidence that you know what the problem is, it’s not yet time to solve it.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem. And the customer decides if the problem is worth solving.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

How To Put The Business Universe On One Page

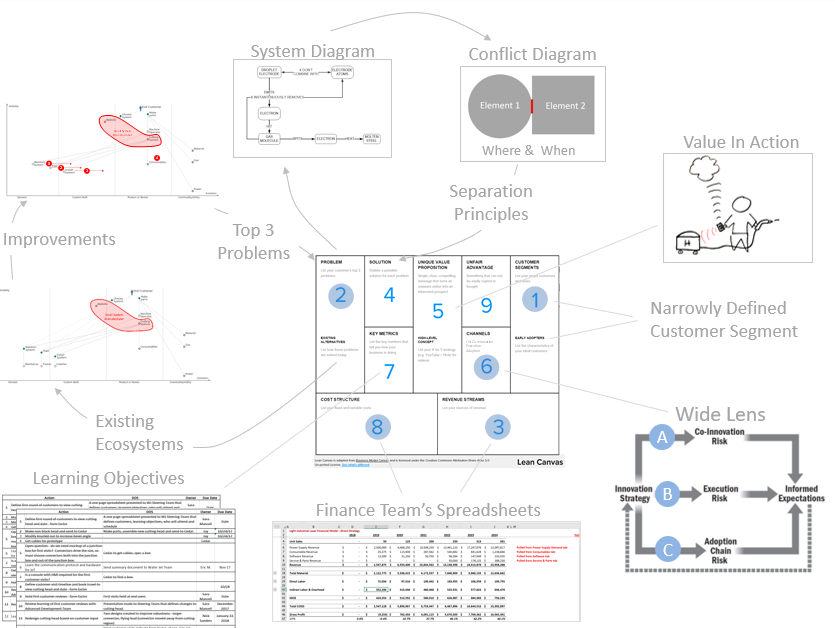

When I want to understand a large system, I make a map. If the system is an ecosystem, I combine Wardley Maps by Simon Wardley with Wide Lens / Winning The Right Game by Ron Adner. On Wardley maps, activities and actors are placed on the map, and related elements are connected. On the left are infant and underdeveloped elements, and on the right are fully developed / commodity elements. It’s like an S-curve that’s been squished flat.

When I want to understand a large system, I make a map. If the system is an ecosystem, I combine Wardley Maps by Simon Wardley with Wide Lens / Winning The Right Game by Ron Adner. On Wardley maps, activities and actors are placed on the map, and related elements are connected. On the left are infant and underdeveloped elements, and on the right are fully developed / commodity elements. It’s like an S-curve that’s been squished flat.

Wide Lens prompts you to consider co-innovation (who needs to innovate for you to be successful) and adoption (who needs to believe your idea is a good one). Winning The Right Game makes you think through the sequence of attracting partners like a visual time-lapse of the ecosystem’s evolution. This is a killer combination that demands you put the whole system on one page – all the players/partners, all the activities sorted by maturity, all the interactions, and the evolution of the partner network and maturity of the system elements. This forces a common understanding of the ecosystem. There’s no way out. Did I say it must fit on one page?

When the large system is a technological system, I make a map. I use the best TRIZ book (Innovation On Demand) by Victor Fey. A functional analysis is performed on the system using noun-verb pairs that are strung together to represent how the system behaves. If you want to drive people crazy, this is the process for you. It requires precise words for each noun (element) and verb (action) pair, and the pairs must hang together in a way that represents the physical system. There can be only one description of the system, and the fun and games don’t stop until the team converges on a single representation of the system. It’s all good fun until someone loses an eye.

When I want to understand a business/technology/product/service offering that has not been done before (think startup), I use Lean Canvas by Ash Maurya. The Lean Canvas requires you to think through all elements of the system and forces you to put it on one page. (Do you see a theme here?) Value proposition, existing alternatives, channel to market, customer segments, metrics, revenue, costs, problems, and solutions – all of them on one page.

And then to blow people’s minds, I combine Wardley Maps, Wide Lens, Winning The Right Game, functional analysis of TRIZ, value in action, and Lean Canvas on one page. And this is what it looks like.

Ash’s Lean Canvas is the backplane. Ron’s Wide Lens supports 6 (Channel), forcing a broader look than a traditional channel view. Ron’s Winning The Right Game and Simon’s Wardley Map are smashed together to support 2 (Existing Alternatives/Problems). A map is created for the existing system with system elements (infants on the left, retirees on the right) and partners/players, which are signified by color (red blob). Then, a second map is created to define the improvements to be made (red circles with arrows toward a more mature state). Victor’s Functional Analysis/System diagram defines the problematic system, and TRIZ tools, e.g., Separation Principles, are used to solve the problem.

When I want to understand a system (ecosystem or technological system), I make a map. And when I want to make a good map, I put it on one page. And when I want to create a new technological system that’s nested in a new business model that’s nested in a new ecosystem, I force myself to put the whole universe on one page.

Image credit – Giuseppe Zeta

Good Teachers Are Better Than Good

Good teachers change your life. They know what you know and bring you along at a pace that’s right for you, not too slowly that you’re bored and not too quickly that your head spins. And everything they do is about you and your learning. Good teachers prioritize your learning above all else.

Good teachers change your life. They know what you know and bring you along at a pace that’s right for you, not too slowly that you’re bored and not too quickly that your head spins. And everything they do is about you and your learning. Good teachers prioritize your learning above all else.

Chris Brown taught me Axiomatic Design. He helped me understand that design is more than what a product does. All meetings and discussions with Chris started with the three spaces – Functional Requirements (FRs) what it does, Design Parameters (DPs) what it looks like, and Process Variables (PVs) how to make it. This was the deepest learning of my professional life. To this day, I am colored by it. And the second thing he taught me was how to recognize functional coupling. If you change one input to the design and two outputs change, that’s functional coupling. You can manage functional coupling if you can see it. But if you can’t see it, you’re hosed. Absolutely hosed.

Vicor Fey taught me TRIZ. He helped me understand the staggering power of words to limit and shape our thinking. I will always remember when he passionately expressed in his wonderful accent, “I hate words!” And to this day, I draw pictures of problems and I avoid words. And the second thing he taught me is that a problem always exists between two things, and those things must touch each other. I make people’s lives miserable by asking – Can you draw me a picture of the problem? And, Which two system elements have the problem, and do they touch each other? And the third thing he taught me was to define problems (Yes, Victor, I know I should say conflicts.) in time. This is amazingly powerful. I ask – “Do you want to solve the problem before it happens, while it happens, or after it happens?” Defining the problem in time is magically informative.

Don Clausing taught me Robust Design. He helped me understand that you can’t pass a robustness test. He said, “If you don’t break it, you don’t know how good it is.” He was an ornery old codger, but he was right. Most tests are stopped before the product fails, and that’s wrong. He also said, “You’ve got to test the old design if you want to know if the new one is better.” To this day, I press for A/B testing, where the old design and new design are tested against the same test protocol. This is much harder than it sounds and much more powerful. He taught me to test designs at stress levels higher than the operating stresses. He said, “Test it, break it, and improve it. And when you run out of time, launch it.” And, lastly, he said, “Improve robustness at the expense of predicting it.” He gave zero value to statistics that predict robustness and 100% value to failure mode-based testing of the old design versus the new one.

The people I work with don’t know Chris, Victor, or Don. But they know the principles I learned from them. I’m a taskmaster when it comes to FRs-DPs-PVs. Designs must work well, be clearly defined by a drawing, and be easy to make. And people know there’s no place in my life for functional coupling. My coworkers know to draw a picture of the problem, and it better be done on one page. And they know the problem must be shown to exist between two things that touch. And they know they’ll get the business from me if they don’t declare that they’re solving it before, during, or after. They know that all new designs must have A/B test results, and the new one must work better than the old one. No exceptions.

I am thankful for my teachers. And I am proud to pass on what they gave me.

Image credit — Christof Timmermann

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski