A Race for Learning – Video Training with TED-Ed

I’ve been thinking about how to use video to train engineers. The trouble with video is it takes time and money to create. But what if you could create lessons using existing video? That’s what the new TED-Ed platform can do. With TED-Ed, any YouTube video can be “flipped” into a customized lesson.

I’ve been thinking about how to use video to train engineers. The trouble with video is it takes time and money to create. But what if you could create lessons using existing video? That’s what the new TED-Ed platform can do. With TED-Ed, any YouTube video can be “flipped” into a customized lesson.

Instead of trying to describe it, I used the new platform to create a video lesson. Click the link below and give it a try. (The platform is still in beta version, so I’m not sure how will go. But that’s how it is with experiments.)

Video lesson: Innovation, Caveman-Style

When answering the questions, it may ask you to sign up for an account. Click the X in the upper right of the message to make it go away, and keep going. If the video does not work at all, poke around the TED-Ed website.

Either way, so we can accelerate our learning and get out in front, please post a comment or two.

Celebrating Three Years of Shipulski On Design

Today is a celebration – three years of Shipulski On Design!

Today is a celebration – three years of Shipulski On Design!

I get lot’s of great feeback, but the best is when you tell me my writing touched you and helped you do your work differently. You may see this as my gift to you, but I see it as your gift to me.

Thank you for reading and commenting.

Below are some highlights for 2012:

Accomplishments in 2012

- Third year of weekly blog posts without missing a beat or repeating (203 posts in total).

- Second year of daily tweets – 1520 in all (@mikeshipulski).

- Top 40 Innovation Bloggers – Innovation Excellence, the web’s top innovation site.

- Sixth consecutive year as Keynote Speaker at International Forum on DFMA.

- Started Pinterest page – cool engineering pictures and video content – (ShipOnDesign).

- Third year of LinkedIn working group – Systematic DFMA Deployment.

- Second year writing a column for Assembly Magazine (6 columns this year).

Top 5 Posts

- Why it’s tough to decide — how to spot unmade decisions – gremlin style.

- Choose your path — the three paths explained – short and good.

- Impossible — well, almost.

- What is Design for Manufacturing and Assembly — the basics – video style.

- When It’s Time For a New Cowpath — great photo

I look forward to a great year 4.

Beyond Dead Reckoning

We’re afraid of technology development because it’s risky. And figuring out where to go is the risky part. To figure out where to go companies use several strategies: advance multiple technologies in parallel; ask the customer; or leave it to company leader’s edict. Each comes with its strengths and weaknesses.

We’re afraid of technology development because it’s risky. And figuring out where to go is the risky part. To figure out where to go companies use several strategies: advance multiple technologies in parallel; ask the customer; or leave it to company leader’s edict. Each comes with its strengths and weaknesses.

I think the best way to figure out where to go is to figure out where you are. And the best way to do that is data-driven S-curve analysis.

To collect data, look to your most recent product launches, say five, and characterize them using a goodness-to-cost ratio. (Think miles per gallon for your technology.) Then plot them chronologically and see how the goodness ratio has evolved – flat, slow growth, steep growth, or decline. The shape of the curve positions your technology within the stages of the S-curve and its location triangulated with contextual clues. You know where you are so you can figure out where to go.

Here’s what the stages feel like and what to do when you’re in them:

Stage 1: Infancy – New physics are used to deliver a known function, but it’s not ready for commercialization. This is like early days of the gasoline-electric hybrid vehicles, where the physics of internal combustion was combined with the physics of batteries. In Stage 1 the elements of the overall system are established, like when Honda developed its first generation Honda Insight and GM its EV1. Prototypes are under test, and they work okay, but not great. In Stage 1, goodness-to-cost is lower than existing technologies (and holding), but the bet is when they mature goodness-to-cost will be best on the planet.

If your previous products were Stage 4 (Maturity) or Stage 5 (Decline), your new project should be in Stage 1. If your existing project is in Stage 1, focus on commercialization. If all your previous projects were (are) in Stage 1, you should focus on commercializing one (moving to Stage 2) at the expense of starting a new one.

Stage 2: Transitional – A product is launched in the market and there is intense competition with existing technologies. In Stage 2, several versions of new technology are introduced (Prius, Prius pluggable, GM’s Volt, Nissan Leaf), and they fight it out. Goodness-to-cost is still less than existing technologies, but there’s some element of the technology that’s attractive. For electric vehicles, think emissions.

If your previous products were Stage 4 (Maturity) or Stage 5 (Decline) and your current project just transitioned from Stage 1, you’re in the right place. In Stage 2, fill gaps in functionality; increase controllability – better controls to improve battery performance; and develop support infrastructure -electric fueling stations.

Stage 3: Growth – Goodness-to-cost increases rapidly, and so do sales. (I think most important for an electric vehicle is miles per charge.)

If you’re in Stage 3, it’s time to find new applications – e.g., electric motorcycles, or shorten energy flow paths – small electric motors at the wheels.

Stage 4: Maturity – The product hits physical limits – flat miles per gallon; hits limits in resources – fossil fuels; hits economic limits – costly carbon fiber body panels to reduce weight; or there’s rapid growth in harmful factors – air pollution.

If you’re in Stage 4, in the short term add auxiliary functions – entertainment systems, mobile hotspot, heated steering wheel, heated washer fluid; or improve aesthetics – like the rise of the good looking small coupe. In the long term, start a Stage 1 project to move to new physics – hydrogen fuel cells.

Stage 5: Decline – New and more effective systems have entered their growth stage – Nissan Leaf outsells Ford pickup trucks.

If you’re in Stage 5, long ago you should have started at Stage 1 project – new physics. If you haven’t, it may be too late.

S-curve analysis guides, but doesn’t provide all the answers. That said, it’s far more powerful than rock-paper-scissors.

(This thinking was blatantly stolen from Victor Fey’s training on Advanced S-Curve Analysis. Thank you, Victor.)

More Risk, Less Consequence

WHY? To grow sales in existing markets and create sales in new markets.

WHY? To grow sales in existing markets and create sales in new markets.

WHAT? Create innovative technologies and design products with more function and less cost.

HOW? Educate the engineering engine.

This is easier said than done, because for years we’ve set one-sided expectations – new products must work and timelines must be met – and driven risk tolerance out of our engineering engine. Now it’s time to inject it back in.

The message – Our thinking must change. We must take more risk, but do it safely by reducing negative consequences of risk.

To reduce negative consequences of risk, we must learn to localize risk through the narrowest and deepest problem definition, and learn to secure the launch so it’s safe to try new things.

We must do more up-front technology work, but learn to do it far more narrowly and deeply. We must learn to hold ourselves accountable to rigorous problem definition, and we must put our best people on technology projects.

To focus creativity we must learn to set seemingly unrealistic time constraints; to focus our actions we can look to a powerful mantra – spend a little, learn a lot.

The trouble with new thinking is it takes new thinking. If you don’t have it, go get it. If you already have it, figure out why you haven’t used it.

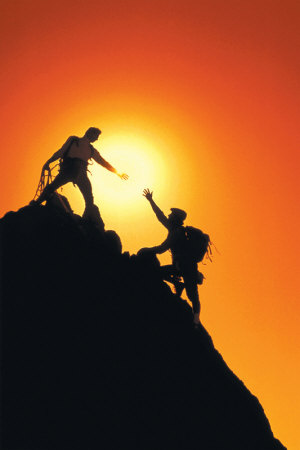

The Pilgrimage of Change

The pilgrimage of change is hard.

The pilgrimage of change is hard.

Before we start, we must believe there’s a way to get there.

Before that, we must believe in the goodness of the destination.

Before that, we must believe there’s a destination.

Before that, we must want something different.

Before that, we must see things as they are.

Before that, we must want to understand.

Before that, we must be curious.

And to do that, we must believe in ourselves.

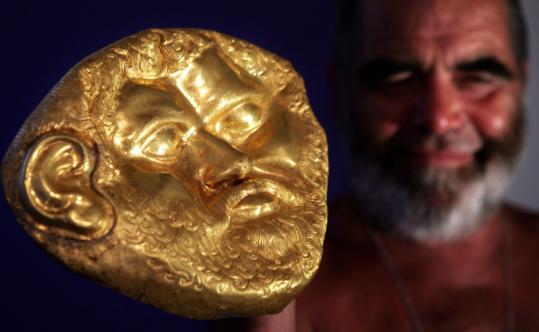

The Archeologist Technologist

Archeologists look back to see what was; they scratch the ground to find what the past left behind; then they study their bounty and speculate backward in time.

Archeologists look back to see what was; they scratch the ground to find what the past left behind; then they study their bounty and speculate backward in time.

But what makes a good archeologist? In a word – belief. Archeologists must believe there’s something out there, something under the dirt waiting for them. Sure, they use their smarts to choose the best place to dig and dig with the best tools, but they know something’s out there and have a burning desire to find it. The first rule of archeology – don’t dig, don’t find.

There’s almost direct overlap between archeologists and technologists, with one difference – where archeologists dig to define the past and technologists dig to define the future.

Technologists must use their knowledge and experience to dig in the right place and must use the best analytical digging tools. Creativity and knowledge are required to decide where to dig, and once unearthed the technologist must interpret the fragments and decide how to knit together the skeleton. But to me, the most important part of the analogy is belief – for the archeologist belief that fossils are buried under the dirt waiting to be discovered and for the technologist belief that technology is buried and waiting to be discovered.

Before powered flight, the Wright brothers believed technology was out there waiting for them. Their first flight was a monumental achievement, and I don’t want to devalue their work, but think about it – what did they create that wasn’t already there? Yes, they knit together technologies in new ways, but they didn’t create the laws of aerodynamics used for the wings (neither did the earliest aerodynamicists); they did not create the laws of thermodynamics behind the gasoline engine (neither did the early thermodynamicists who measured existing phenomena to make the laws); and they didn’t create the wood for the structure. But what they did do is dig for technology.

Space travel – for most of our history just a dream. But decades before rocket technology, it was all there waiting – the periodic table to make the fuel, the physics to make thrust, and the mechanics to create the structure. Natural resources and technologies were quilted together and processed in new ways, yes. But the technologies, or the rules to create them, were already there waiting to be discovered. And what Goddard did was dig.

The archeologist-technologist analogy can be helpful, but the notion of preexisting technology is way out there – it smacks of predestination in which I don’t believe.

But what I do believe in is belief – belief you have the capability to discover a forward-looking fossil – a future genus that others thought impossible. But only if you dig.

The first rule of technology – don’t dig, don’t find.

A Race To The Top

We all want to increase sales. But to do do this, our products must offer a better value proposition – they must increase the goodness-to-cost ratio. And to do this we increase goodness and decrease cost. (No argument here – this is how everyone does it.) When new technologies mature, we design them in to increase goodness and change manufacturing and materials to reduce cost. Then, we sell. This is the proven cowpath. But there’s a problem.

We all want to increase sales. But to do do this, our products must offer a better value proposition – they must increase the goodness-to-cost ratio. And to do this we increase goodness and decrease cost. (No argument here – this is how everyone does it.) When new technologies mature, we design them in to increase goodness and change manufacturing and materials to reduce cost. Then, we sell. This is the proven cowpath. But there’s a problem.

The problem is everyone is thinking this way. You’re watching/developing the same technologies as your competitors; improving the same manufacturing processes; and trying the same materials. On its own, this a recipe for hyper-competition. But with the sinking economy driving more focus on fewer consumers, price is the differentiator. With this cowpath it’s a race to the bottom.

But there’s a better way where there are no competitors and millions (maybe billions) of untapped consumers clamoring for new products. Yes, it’s based on the time-tested method of improving the goodness-to-cost ratio, but there’s a twist – instead of more it’s less. The ratio is increased with less goodness and far less cost. Since no one in their right mind will take this less-with-far-less approach, there is no competition – it’s just you. And because you will provide less goodness, you must sell where others don’t – into the untapped sea of yet-to-be consumers of developing world. With less-with-far-less it’s a race to the top.

Technology is the most important element of less-with-far-less. By reducing some goodness requirements and dropping others all together, immature technologies become viable. You can incorporate fledgeling technologies sooner and commercialize products with their unreasonably large goodness-to-cost ratios. The trick – think less output and narrow-banded goodness.

Immature technologies have improved goodness-to-cost ratios (that’s why we like them), but their output is low. But when a product is designed to require less output, previously immature technologies become viable. Sure, there’s a little less goodness, but the cost structure is far less – just right for the developing world.

Immature technologies are more efficient and smaller, but their operating range is small. But when a product is designed to work within a narrow band of goodness, technologies become viable sooner. Yes, the product does less, but the cost structure is far less – a winning combination for the developing world.

Less-with-far-less makes the product fit the technology – that’s not the hard part. And less-with-far-less makes the product fit the developing world – not hard. In our all-you-can-eat world, where more is seen as the only way, we can’t comprehend how less can win the race to the top. The hard part is less.

Less-with-far-less is not limited by technology or market – it’s limited because we can’t see less as more.

A Fraternity of Team Players

It’s easy to get caught up in what others think. (I fall into that trap myself.) And it’s often unclear when it happens. But what is clear: it’s not good for anyone.

It’s easy to get caught up in what others think. (I fall into that trap myself.) And it’s often unclear when it happens. But what is clear: it’s not good for anyone.

It’s hard to be authentic, especially with the Fraternity of Team Players running the show, because, as you know, to become a member their bylaws demand you take their secret oath:

I [state your name] do solemnly swear to agree with everyone, even if I think differently. And in the name of groupthink, I will bury my original ideas so we can all get along. And when stupid decisions are made, I will do my best to overlook fundamentals and go along for the ride. And if I cannot hold my tongue, I pledge to l leave the meeting lest I utter something that makes sense. And above all, in order to preserve our founding fathers’ externally-validated sense of self, I will feign ignorance and salute consensus.

It’s not okay that the fraternity requires you check your self at the door. We need to redefine what it means to be a team player. We need to rewrite the bylaws.

I want to propose a new oath:

I [state your name] do solemnly swear to think for myself at all costs. And I swear to respect the thoughts and feelings of others, and learn through disagreement. I pledge to explain myself clearly, and back up my thoughts with data. I pledge to stand up to the loudest voice and quiet it with rational, thoughtful discussion. I vow to bring my whole self to all that I do, and to give my unique perspective so we can better see things as they are. And above all, I vow to be true to myself.

Before you’re true to your company, be true to yourself. It’s best for you, and them.

Separation of church and state, yes; separation of team player and self, no.

Less-With-Far-Less for the Developing World

The stalled world economy will make growth difficult, and companies are digging in for the long haul, getting ready to do more of what they do best – add more function and features, sell more into existing markets, and sell more to existing customers. More of the same, but better. But growth will not come easy with more-on-more thinking. It will be more-on-more trench warfare – ugly hand-to-hand combat with little ground gained. It’s time for another way. It’s time for less. It’s time to create new markets with less-with-far-less thinking.

The stalled world economy will make growth difficult, and companies are digging in for the long haul, getting ready to do more of what they do best – add more function and features, sell more into existing markets, and sell more to existing customers. More of the same, but better. But growth will not come easy with more-on-more thinking. It will be more-on-more trench warfare – ugly hand-to-hand combat with little ground gained. It’s time for another way. It’s time for less. It’s time to create new markets with less-with-far-less thinking.

Real growth will come from markets and consumers that don’t exist. Real (and big) growth will come from the developing world. They’re not buying now, but they will. They will when product are developed that fit them. But here’s the kicker – products for the developed world cannot be twisted and tweaked to fit. Your products must be re-imagined.

The fundamentals are different in the developing world. Three important ones are – ability to pay, population density, and literacy/skill.

The most important fundamental is the developing world’s ability to pay. They will buy, but to buy products must cost 10 to 100 times less. (No typo here – 10 to 100 times less.) Traditional cost reduction approaches such as Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DFMA) won’t cut it – their 50% cost reductions are not even close. Reinvention is needed; radical innovation is needed; fundamental innovation is needed. Less-with-far-less thinking is needed.

To achieve 10-100X cost reductions, the product must do less and do it far more efficiency (with far less). Product functionality must be decimated – ripped off the bone until only bone remains. The product must do only one thing. Not two – one. The product must be stripped to its essence, and new technology must be developed to radically improve efficiency of delivering its essence. Products for the developing world will require higher levels of technology than products for the developed world.

Radical narrowing of functionality will make viable the smaller, immature, more efficient technologies. Infant technologies usually have lower output and less breadth, but that’s just what’s needed – narrow, deep, and less. Less-with-far-less.

In the developing world, population density is low. People are spread out, and rural is the norm. And it’s not developed world rural, it’s three-day-hike rural. In the developing world, people don’t go to products; products go to people. If it’s not portable, it won’t sell. And developing world portable does not mean wheels – it means backpack. Your products must fit in a backpack and must be light enough to carry in one.

Big, stationary, expensive equipment is not exempt. It also must fit in a backpack. And this cannot be achieved with twist-and-bend engineering. To fit in a backpack, the product must be stripped naked and new technology must be developed to radically improve efficiency. This requires radical narrowing, radical reimagining, and radical innovation. It requires less-with-far-less thinking. (And if it doesn’t run on batteries, it should at least have battery backup to deal with rolling blackouts.)

People in the developing world are intelligent, but most cannot read well and have little experience with developed world products. Where the developed world’s solution is picture-based installation instructions, less-with-far-less products for the developing world demand no instructions. For the developing world, the instruction manual is the on button. And this requires serious technology – software algorithms fed by low cost sensors. And the only way it’s possible is by distilling the product to its essence. Algorithms, yes, but algorithms to do only one thing very well. Less-with-far-less.

The developed world makes products with output that requires judgment – multi-colored graphical output that lets the user decide if things went well. Products for the developing world must have binary output – red/green, beep/no-beep. Less-with-far-less. But again, this seemingly lower-level functionality (a green light versus a digital display) actually requires more technology. The product must interpret results and decide if it’s good – much harder than a sexy graphical output that requires interpretation and judgement.

Creating products for the developing world requires different thinking. Instead of adding more functions and features, it’s about creating new technologies that do one thing very well (and nothing more) and do it with super efficiency. Products for the developing world require higher technologies than those for the developed world. And done well, the developed world will buy them. But the crazy thing is, the less-with-far-less products that will be a hit in the developing world will boomerang back and be an even bigger hit in the developed world.

You might be a superhero if…

- Using just dirt, rocks, and sticks, you can bring to life a product that makes life better for society.

- Using just your mind, you can radically simplify the factory by changing the product itself.

- Using your analytical skills, you can increase product function in ways that reinvent your industry.

- Using your knowledge of physics, you can solve a longstanding manufacturing problem by making a product insensitive to variation.

- Using your knowledge of Design for Manufacturing and Assembly, you can reduce product cost by 50%.

- Using your knowledge of materials, you can eliminate a fundamental factory bottleneck by changing what the product is made from.

- Using your curiosity and creativity, you can invent and commercialize a product that creates a new industry.

- Using your superpowers, you think you can fix a country’s economy one company at a time.

How To Accelerate Engineers Into Social Media

Engineers fear social media, but shouldn’t. Our fear comes from lack of knowledge around information flow. Because we don’t understand how information flow works, we stay away. But our fear is misplaced – with social media information flow is controllable.

Engineers fear social media, but shouldn’t. Our fear comes from lack of knowledge around information flow. Because we don’t understand how information flow works, we stay away. But our fear is misplaced – with social media information flow is controllable.

For engineers, one-way communication is the best way to start. Engineers should turn on the information tap and let information flow to them. Let the learning begin.

At first, stay away from FaceBook – it’s the most social (non-work feel), least structured, and most difficult to understand – at least to me.

To start, I suggest LinkedIn – it’s the least social (most work-like) and highly controllable. It’s simple to start – create an account, populate your “resume stuff” (as little as you like) and add some connections (people you know and trust). You now have a professional network who can see your resume stuff and they can see yours. But no one else can, unless you let them. Now the fun part – find and join a working group in your interest area. A working group is group of like-minded people who create work-related discussions on a specific topic. Mine is called Systematic DFMA Deployment. You can search for a group, join (some require permission from the organizer), and start reading the discussions. The focused nature of the groups is comforting and you can read discussions without sharing any personal information. To start two-way communication, you can comment on a discussion.

After LinkedIn, engineers should try Twitter. Tweets (sounds funny, doesn’t it?) are sentences (text only) that are limited to 140 characters. With Twitter, one-way communication is the way to start – no need to share information. Just create an account and you’re ready to learn. With LinkedIn it’s about working groups, and with Twitter it’s about hashtags (#). Hashtags create focus with Twitter and make it searchable. For example, if the tweet creator uses #DFMA in the sentences, you can find it. Search for #DFMA and you’ll find tweets (sub-140 character sentences) related to design for manufacturing and assembly. When you find a hashtag of interest, monitor those tweets. (You can automate hashtag searches – HootSuite – but that’s for later). And when you find someone who consistently creates great content, you can follow them. Once followed, all their tweets are sent to your Twitter account (Twitter feed). To start two-way communication you can retweet (resend a tweet you like), send a direct message to someone (like a short email), or create your own tweet.

Twitter’s format comforts me – short, dense bursts of sentences and no more. Long tweets are not possible. But a tweet can contain a link to a website which points to a specific page on the web. To me it’s a great combination – short sentences that precisely point to the web.

With engineers and social media, the goal is to converge on collaboration. Ultimately, engineers move from one-way communication to two-way communication, and then to collaboration. Collaboration on LinkedIn and Twitter allows engineers to learn from (and interact with) the world’s best subject matter experts. Let me say that again – with LinkedIn and Twitter, engineers get the latest technical data, analyses, and tools from the best people in the world. And it’s all for free.

For engineers, social and media are the wrong words. For engineers, the right words are – controlled, focused, work-related information flow. And when engineers get comfortable with information flow, they’ll converge on collaboration. And with collaboration, engineers will learn from each other, help each other, innovate and, even, create personal relationships with each other.

Companies still look at social media as a waste of work time, and that’s especially true when it comes to their engineers. But that’s old thinking. More bluntly, that’s dangerous thinking. When their engineers use social media, companies will develop better products and technologies and commercialize them faster.

Plain and simple, companies that accelerate their engineers into social media will win.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski