When You Have No Slack Time…

When you have no slack time, you can’t start new projects.

When you have no slack time, you can’t start new projects.

When you have no slack time, you can’t run toward the projects that need your help.

When you have no slack time, you have no time to think.

When you have no slack time, you have no time to learn.

When you have no slack time, there’s no time for concern for others.

When you have no slack time, there’s no time for your best judgment.

When there is no slack time, what used to be personal becomes transactional.

When there is no slack time, any hiccup creates project slip.

When you have no slack time, the critical path will find you.

When no one has slack time, one project’s slip ripples delay into all the others.

When you have no slack time, excitement withers.

When you have no slack time, imagination dies.

When you have no slack time, engagement suffers.

When you have no slack time, burnout will find you.

When you have no slack time, work sucks.

When you have no slack time, people leave.

I have one question for you. How much slack time do you have?

“Hurry up Leonie, we are late…” by The Preiser Project is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Testing is an important part of designing.

When you design something, you create a solution to a collection of problems. But it goes far beyond creating the solution. You also must create objective evidence that demonstrates that the solution does, in fact, solve the problems. And the reason to generate this evidence is to help the organization believe that the solution solves the problem, which is an additional requirement that comes with designing something. Without this belief, the organization won’t go out to the customer base and convince them that the solution will solve their problems. If the sales team doesn’t believe, the customers won’t believe.

When you design something, you create a solution to a collection of problems. But it goes far beyond creating the solution. You also must create objective evidence that demonstrates that the solution does, in fact, solve the problems. And the reason to generate this evidence is to help the organization believe that the solution solves the problem, which is an additional requirement that comes with designing something. Without this belief, the organization won’t go out to the customer base and convince them that the solution will solve their problems. If the sales team doesn’t believe, the customers won’t believe.

In school, we are taught to create the solution, and that’s it. Here are the drawings, here are the materials to make it, here is the process documentation to build it, and my work here is done. But that’s not enough.

Before designing the solution, you’ve got to design the tests that create objective evidence that the solution actually works, that it provides the right goodness and it solves the right problems. This is an easy thing to say, but for a number of reasons, it’s difficult to do. To start, before you can design the right tests, you’ve got to decide on the right problems and the right goodness. And if there’s disagreement and the wrong tests are defined, the design community will work in the wrong areas to generate the wrong value. Yes, there will be objective evidence, and, yes, the evidence will create a belief within the organization that problems are solved and goodness is achieved. But when the sales team takes it to the customer, the value proposition won’t resonate and it won’t sell.

Some questions to ask about testing. When you create improvements to an existing product, what is the family of tests you use to characterize the incremental goodness? And a tougher question: When you develop a new offering that provides new lines of goodness and solves new problems, how do you define the right tests? And a tougher question: When there’s disagreement about which tests are the most important, how do you converge on the right tests?

Image credit — rjacklin1975

Problems, Solutions, and Complaints

If you see a problem, tell someone. But, also, tell them how you’d like to improve things.

If you see a problem, tell someone. But, also, tell them how you’d like to improve things.

Once you see a problem, you have an obligation to seek a solution.

Complaining is telling someone they have a problem but stopping short of offering solutions.

To stop someone from complaining, ask them how they might make the situation better.

Problems are good when people use them as a forcing function to create new offerings.

Problems are bad when people articulate them and then go home early.

Thing is, problems aren’t good or bad. It’s our response that determines their flavor.

If it’s your problem, it can never be our solution.

Sometimes the best solution to a problem is to solve a different one.

Problem-solving is 90% problem definition and 10% getting ready to define the problem.

When people don’t look critically at the situation, there are no problems. And that’s a big problem.

Big problems require big solutions. And that’s why it’s skillful to convert big ones into smaller ones.

Solving the right problem is much more important than solving the biggest problem.

If the team thinks it’s impossible to solve the problem, redefine the problem and solve that one.

You can relabel problems as “opportunities” as long as you remember they’re still problems

When it comes to problem-solving, there is no partial credit. A problem is either solved or it isn’t.

Why are people leaving your company?

People don’t leave a company because they feel appreciated.

People don’t leave a company because they feel appreciated.

People don’t leave a company because they feel part of something bigger than themselves.

People don’t leave a company because they see a huge financial upside if they stay.

People don’t leave a company because they are treated with kindness and respect.

People don’t leave a company because they can make less money elsewhere.

People don’t leave a company because they see good career growth in their future.

People don’t leave a company because they know all the key players and know how to get things done.

People don’t leave the company so they can abandon their primary care physician.

People don’t leave a company because their career path is paved with gold.

People don’t leave a company because they are highly engaged in their work.

People don’t leave a company because they want to uproot their kids and start them in a new school.

People don’t leave a company because their boss treats them too well.

People don’t leave a company because their work is meaningful.

People don’t leave a company because their coworkers treat them with respect.

People don’t leave a company because they want to pay the commission on a real estate transaction.

People don’t leave a company because they’ve spent a decade building a Trust Network.

People don’t leave a company because they want their kids to learn to trust a new dentist.

People don’t leave a company because they have a flexible work arrangement.

People don’t leave a company because they feel safe on the job.

People don’t leave a company because they are trusted to use their judgment.

People don’t leave the company because they want the joy that comes from rolling over their 401k.

People don’t leave a company when they have the tools and resources to get the work done.

People don’t leave a company when their workload is in line with their capacity to get it done.

People don’t leave a company when they feel valued.

People don’t leave a company so they can learn a whole new medical benefits plan.

People don’t leave a job because they get to do the work the way they think it should be done.

So, I ask you, why are people leaving your company?

“Penguins on Parade” by D-Stanley is licensed under

Stop reusing old ideas and start solving new problems.

Creating new ideas is easy. Sit down, quiet your mind, and create a list of five new ideas. There. You’ve done it. Five new ideas. It didn’t take you a long time to create them. But ideas are cheap.

Creating new ideas is easy. Sit down, quiet your mind, and create a list of five new ideas. There. You’ve done it. Five new ideas. It didn’t take you a long time to create them. But ideas are cheap.

Converting ideas into sellable products and selling them is difficult and expensive. A customer wants to buy the new product when the underlying idea that powers the new product solves an important problem for them. In that way, ideas whose solutions don’t solve important problems aren’t good ideas. And in order to convert a good idea into a winning product, dirt, rocks, and sticks (natural resources) must be converted into parts and those parts must be assembled into products. That is expensive and time-consuming and requires a factory, tools, and people that know how to make things. And then the people that know how to sell things must apply their trade. This, too, adds to the difficulty and expense of converting ideas into winning products.

The only thing more expensive than converting new ideas into winning products is reusing your tired, old ideas until your offerings run out of sizzle. While you extend and defend, your competitors convert new ideas into new value propositions that bring shame to your offering and your brand. (To be clear, most extend-and-defend programs are actually defend-and-defend programs.) And while you reuse/leverage your long-in-the-tooth ideas, start-ups create whole new technologies from scratch (new ideas on a grand scale) and pull the rug out from under you. The trouble is that the ultra-high cost of extend-and-defend is invisible in the short term. In fact, when coupled with reuse, it’s highly profitable in the moment. It takes years for the wheels to fall off the extend-and-defend bus, but make no mistake, the wheels fall off.

When you find the urge to create a laundry list of new ideas, don’t. Instead, solve new problems for your customers. And when you feel the immense pressure to extend and defend, don’t. Instead, solve new problems for your customers.

And when all that gets old, repeat as needed.

“Cave paintings” by allspice1 is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

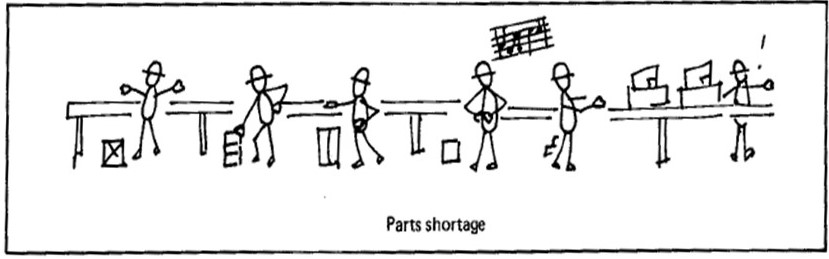

Supply chains don’t have to break.

We’ve heard a lot about long supply chains that have broken down, parts shortages, and long lead times. Granted, supply chains have been stressed, but we’ve designed out any sort of resiliency. Our supply chains are inflexible, our products are intolerant to variation and multiple sources for parts, and our organizations have lost the ability to quickly and effectively redesign the product and the parts to address issues when they arise. We’ve pushed too hard on traditional costing and have not placed any value on flexibility. And we’ve pushed too hard on efficiency and outsourced our design capability so we can no longer design our way out of problems.

We’ve heard a lot about long supply chains that have broken down, parts shortages, and long lead times. Granted, supply chains have been stressed, but we’ve designed out any sort of resiliency. Our supply chains are inflexible, our products are intolerant to variation and multiple sources for parts, and our organizations have lost the ability to quickly and effectively redesign the product and the parts to address issues when they arise. We’ve pushed too hard on traditional costing and have not placed any value on flexibility. And we’ve pushed too hard on efficiency and outsourced our design capability so we can no longer design our way out of problems.

Our supply chains are inflexible because that’s how we designed them. The products cannot handle parts from multiple suppliers because that’s how we designed them. And the parts cannot be made by multiple suppliers because that’s how we designed them.

Now for the upside. If we want a robust supply chain, we can design the product and the parts in a way that makes a robust supply chain possible. If we want the flexibility to use multiple suppliers, we can design the product and parts in a way that makes it possible. And if we want the capability to change the product to adapt to unforeseen changes, we can design our design organizations to make it possible.

There are established tools and methods to help the design community design products in a way that creates flexibility in the supply chain. And those same tools and methods can also help the design community create products that can be made with parts from multiple suppliers. And there are teachers who can help rebuild the design community’s muscles so they can change the product in ways to address unforeseen problems with parts and suppliers.

How much did it cost you when your supply chain dried up? How much did it cost you the last time a supplier couldn’t deliver your parts? How much did it cost you when your design community couldn’t redesign the product to keep the assembly line running? Would you believe me if I told you that all those costs are a result of choices you made about how to design your supply chain, your product, your parts, and your engineering community?

And would you believe me if I told you could make all that go away? Well, even if you don’t believe me, the potential upside of making it go away is so significant you may want to look into it anyway.

Image credit — New Manufacturing Challenge, Suzaki, 1987.

What do you like to do?

I like to help people turn complex situations into several important learning objectives.

I like to help people turn complex situations into several important learning objectives.

I like to help people turn important learning objectives into tight project plans.

I like to help people distill project plans into a single-page spreadsheet of who does what and when.

I like to help people start with problem definition.

I like to help people stick with problem definition until the problems solve themselves.

I like to help people structure tight project plans based on resource constraints.

I like to help people create objective measures of success to monitor the projects as they go.

I like to help people believe they can do the almost impossible.

I like to help people stand three inches taller after they pull off the unimaginable.

I like to help people stop good projects so they can start amazing ones.

If you want to do more of what you like and less of what you don’t, stop a bad project to start a good one.

So, what do you like to do?

Image credit — merec0

Three Things for the New Year

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Some things will be the same and some will be different. The trouble is that we won’t know which is which until we do. We can speculate on how it will be different, but the Universe doesn’t care about our speculation. Sure, it can be helpful to think about how things may go, but as long as we hold on to the may-ness of our speculations. And we don’t know when we’ll know. We’ll know when we know, but no sooner. Even when the Operating Plan declares the hardest of hard dates, the Universe sets the learning schedule on its own terms, and it doesn’t care about our arbitrary timelines.

What to do?

Step 1. Try three new things. Choose things that are interesting and try them. Try to try them in parallel as they may interact and inform each other. Before you start, define what success looks like and what you’ll do if they’re successful and if they’re not. Defining the follow-on actions will help you keep the scope small. For things that work out, you’ll struggle to allocate resources for the next stages, so start small. And if things don’t work out, you’ll want to say that the projects consumed little resources and learned a lot. Keep things small. And if that doesn’t work, keep them smaller.

Step 2. Rinse and repeat.

I wish you a happy and safe New Year. And thanks for reading.

Mike

“three” by Travelways.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Effective Interactions During Difficult Times

When times are stressful, it’s more difficult to be effective and skillful in our interactions with others. Here are some thoughts that could help.

When times are stressful, it’s more difficult to be effective and skillful in our interactions with others. Here are some thoughts that could help.

Decide how you want to respond, and then respond accordingly.

Before you respond, take a breath. Your response will be better.

If you find yourself responding before giving yourself permission, stop your response and come clean.

Better responses from you make for even better responses from others.

If you interrupt someone in the middle of their sentence so you can make your point, you made a different point.

If you find yourself preparing your response while listening to someone, that’s not listening.

If you recognize you’re not listening, now there are at least two people who know the truth.

When there are no words coming from your mouth, that doesn’t constitute listening.

The strongest deterrent to listening is talking.

If you disagree with one element of a person’s position, you can, at the same time, agree with other elements of their position. That’s how agreement works.

If you start with agreement, even the smallest bit, disagreement softens.

Before you can disagree, it’s important to listen and understand. And it’s the same with agreement.

It’s easy to agree if that’s what you want to accomplish. And it’s the same for disagreement.

If you want to move toward agreement, start with understanding.

If you want to demonstrate understanding, start with listening.

If you want to demonstrate good listening, start with kindness.

Here are three mantras I find helpful:

Talk less to listen more.

Before you respond, take a breath.

Kindness before agreement.

“Rock-em” by REL Waldman is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Elevating the Importance of Manufacturing and Construction

Restaurants aren’t open as much as they used to be because they cannot hire enough people to do the work. Simply put, there are too few people who want to take the orders; cook the food; deliver food to the tables; clear the tables; and wash the dishes. Sure, it’s an inconvenience that we can’t get a table, but because there are other ways to get food no one will starve because restaurants open. And while some restaurants will go out of business, this situation doesn’t fundamentally constrain the economy.

Restaurants aren’t open as much as they used to be because they cannot hire enough people to do the work. Simply put, there are too few people who want to take the orders; cook the food; deliver food to the tables; clear the tables; and wash the dishes. Sure, it’s an inconvenience that we can’t get a table, but because there are other ways to get food no one will starve because restaurants open. And while some restaurants will go out of business, this situation doesn’t fundamentally constrain the economy.

And the situation is similar with manufacturing and construction: no one wants those jobs either. But, that’s where the similarities end. The shortfall of people who want to work in manufacturing and construction will constrain the economy and prevent the renewal of our infrastructure. Gone are the days of relying on other countries to make all your products because we now know it’s not the most cost-effective way to go. But if there is no one willing to make the products, there will be no products made. And if there is no one willing to build the roads and bridges, roads and bridges will suffer. And if there are no products, no good roads, and no safe bridges, there can be no strong economy.

While there is disagreement around why people don’t want to work in manufacturing and construction, I will propose three for your consideration.

Firstly, the manufacturing and construction sectors have an image problem. People don’t see these jobs as high-tech, high-status jobs where the working environment is clean and safe. In short, people don’t see these jobs as jobs they can be proud and they don’t think others will think highly of them if they say they work in manufacturing or construction. And because of the history of layoffs, people don’t see these jobs as secure and predictable and don’t see them as reliable sources of income. This may not be the case for all people, but I think it applies to a lot of people.

Secondly, the manufacturing and construction sectors don’t pay enough. People don’t see these jobs as viable mechanisms to provide a solid standard of living for themselves and their families. This is a generalization, but I think it holds true.

Thirdly, the manufacturing and construction sectors require specialized knowledge, skills, and abilities skills that are not taught in traditional high schools or colleges. And without these qualifications, people are reluctant to apply. And if they do apply and a company hires them even though they don’t have the knowledge, skills, and abilities, companies must invest in training which creates a significant cost hurdle.

So, what are we to do?

To improve their image, the manufacturing and construction trade organizations and professional societies can come together and create a coordinated education program to change what people think about their industries. And states can help by educating their citizens on the importance of manufacturing and construction to the health of the states’ economies. This will be a long road, but I think it’s time to start.

To attract new talent, the manufacturing and construction sectors must pay a higher wage. In the short term, profits may be reduced, but imagine how much profits will be reduced if there are no people to build the products or fix the bridges. And over the long term, with improved business processes and working methods, profits will grow.

To train people to work in manufacturing and construction, we can reinstitute the Training Within Industry program of the 1940s. The Manufacturing Extension Partnership programs within the states can be a center of mass for this work along with the Construction Industry Institute and other construction trade organizations.

It’s time to join forces to make this happen.

The Two Sides of the Story

When you tell the truth and someone reacts negatively, their negativity is a surrogate for significance.

When you tell the truth and someone reacts negatively, their negativity is a surrogate for significance.

When you withhold the truth because someone will react negatively, you do everyone a disservice.

When you know what to do, let someone else do it.

When you’re absolutely sure what to do, maybe you’ve been doing it too long.

When you’re in a situation of complete uncertainty, try something. There’s no other way.

When you’re told it’s a bad idea, it’s probably a good one, but for a whole different reason.

When you’re told it’s a good idea, it’s time to come up with a less conventional idea.

When you’re afraid to speak up, your fear is a surrogate for importance.

When you’re afraid to speak up and you don’t, you do your company a disservice.

When you speak up and are met with laughter, congratulations, your idea is novel.

When you get angry, that says nothing about the thing you’re angry about and everything about you.

When someone makes you angry, that someone is always you.

When you’re afraid, be afraid and do it anyway.

When you’re not afraid, try harder.

When you’re understood the first time you bring up a new idea, it’s not new enough.

When you’re misunderstood, you could be onto something. Double down.

When you’re comfortable, stop what you’re doing and do something that makes you uncomfortable.

It’s time to get comfortable with being uncomfortable.

“mirror-image pickup” by jasoneppink is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski