Archive for the ‘Uncertainty’ Category

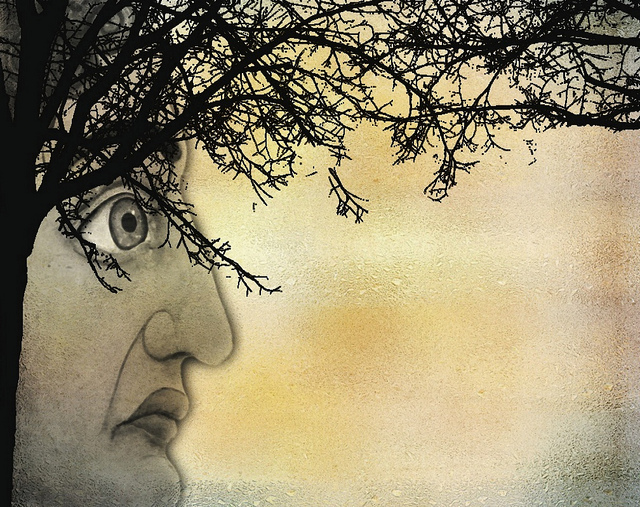

How to wallow in the mud of uncertainty.

Creativity and innovation are dominated by uncertainty. And in the domain of uncertainty, not only are the solutions unknown, the problems are unknown. And yet, we still try to use the tried-and-true toolbox of certainty even after it’s abundantly clear those wrenches don’t fit.

Creativity and innovation are dominated by uncertainty. And in the domain of uncertainty, not only are the solutions unknown, the problems are unknown. And yet, we still try to use the tried-and-true toolbox of certainty even after it’s abundantly clear those wrenches don’t fit.

When wallowing in the mud of uncertainty and company leaders ask, “When will you be done?”, the only real answer is a description of the next thing you’ll try to learn. “We will learn if Step 1 is possible.” And then the predicted response, “Well, when will you be done with that?” The only valid response is, “It depends.” Though truthful, this goes over like a lead balloon. And the dialog continues – “Okay, then, what is Step 2?” The unpalatable answer, “It depends. If Step 1 is successful, we’ll move onto Step 2, but if Step 1 is unsuccessful, we’ll step back and regroup.” This, too, though truthful, is unsatisfactory.

When doing creative work, there’s immense pressure to be done on time. But, that pressure is inappropriate. Yes, there can be pressure to learn quickly and effectively, but the expectation to be done within an arbitrary timeline is ludicrous. Managers don’t know this, but when they demand a completion date for a task that has never been done before, the people doing the creative work know the manager doesn’t know what they’re doing. They won’t tell the manager what they think, but they definitely think it. And when pushed to give a completion date, they’ll give one, knowing full well the predicted date is just as arbitrary as the manager’s desired timeline.

But learning objectives can create common ground. Starting with “We want to learn if…”, learning objectives define what the project team must learn. Though there’s no agreement on when things will be completed, everyone can agree on the learning objectives. And with clearly defined learning objectives and measurable definitions of success, the project can move forward with consensus. There is still consternation over the lack of hard deadlines for the learning objectives, but there is agreement on the sequence of events, tests protocols or analyses that will be carried out to learn what must be learned.

Two rules to live by: If you know when you’ll be done, you’re not doing innovation. And if no one is surprised by the solution, you’re not doing creative work.

Image credit – Michael Carian

Moving from Static to Dynamic

At some point, what worked last time won’t work this time. It’s not if the business model will go belly-up, it’s when. There are two choices. We can bury our heads in the sands of the status quo, or we can proactively observe the world in a forward-looking way and continually reorient ourselves as we analyze and synthesize what we see.

At some point, what worked last time won’t work this time. It’s not if the business model will go belly-up, it’s when. There are two choices. We can bury our heads in the sands of the status quo, or we can proactively observe the world in a forward-looking way and continually reorient ourselves as we analyze and synthesize what we see.

The world is dynamic, but we behave like it’s static. We have massive intellectual inertia around what works today. In a rearward-looking way, we want to hold onto today’s mental models and we reject the natural dynamism swirling around us. But the signals are clear. There’s cultural change, political change, climate change and population change. And a lower level, there’s customer change, competition change, technology change, coworker change, family change and personal change. And still, we cling to static mental models and static business models. But how to move from static to dynamic?

Continual observation and scanning is a good place to start. And since things become real when resources are allocated, allocating resources to continually observe and scan sends a strong message. We created this new position because things are changing quickly and we need to be more aware and more open minded to the dynamic nature of our world. Sure, observation should be focused and there should be a good process to decide on focus areas, but that’s not the point. The point is things are changing and we will continually scan for storms brewing just over the horizon. And, yes, there should be tools and templates to record and organize the observations, but the important point is we are actively looking for change in our environment.

Observation has no value unless the observed information is used for orientation in the new normal. For orientation, analysis and synthesis is required across many information sources to develop ways to deal with the unfamiliar and unforeseen. [1] It’s important to have mechanisms to analyze and synthesize, but the value comes when beliefs are revised and mental models are updated. Because the information cuts against history, tradition and culture, to make shift in thinking requires diversity of perspective, empathy and a give-and-take dialog. [1] It’s a nonlinear process that is ironed out as you go. It’s messy and necessary.

It’s risky to embrace a new perspective, but it’s far riskier to hold onto what worked last time.

[1] Osinga, Frans, P.B. Science, Strategy and War, The strategic theory of John Boyd. New York: Routledge, 2007.

image credit – gabe popa

Learn in small batches, rinse and repeat.

When the work is new, it can’t be defined and managed like work that has been done before.

When the work is new, it can’t be defined and managed like work that has been done before.

Sometimes there’s a tendency to spend months to define the market, the detailed specification and the project timeline and release the package as a tidal wave that floods the organization with new work. Instead, start with a high-level description of the market, a rough specification and the major project milestones, all of which will morph, grow and inform each other as the team learns. Instead of a big batch, think bite-sized installments that build on each other. Think straw-man that gets its flesh as the various organizations define their learning objectives and learn them.

Instead of target customer segments and idealized personas, define how the customers will interact with the new product or service. Use the storyboard format to capture sequence of events (what they do), the questions they ask themselves and how they know they’ve done it right. Make a storyboard for the top three to five most important activities the customers must do. There’s good learning just trying to decide on the top three to five activities, never mind the deep learning that comes when you try to capture real activities of real customers. [Hint – the best people to capture real customer activities are real customers.]

Instead of a detailed list of inputs and outputs, fill in the details of the storyboards. Create close-ups of the user interfaces and label the dials, buttons and screens. When done well, the required inputs and outputs bubble to the surface. And define the customer’s navigation path, as it defines the sequence of things and where the various inputs come to be and the various outputs need to be. What’s nice is learning by iteration can be done quickly since its done in the domain of whiteboards and markers.

Instead of defining everything, just define what’s new and declare everything else is the same as last time.

The specification for the first prototypes is to bring the storyboards to life and to show the prototypes to real customers. Refine and revise based on the learning, and rinse and repeat, as needed.

As the design migrates toward customer value and confidence builds, it’s then time to layer on the details and do a deep dive into the details – specs, test protocols, manufacturing, sales and distribution.

At early stages of innovation work, progress isn’t defined by activity, it’s defined by learning. And it can look like nothing meaningful is happening as there is a lot of thinking and quiet time mixed in with infrequent bursts active activity. But that’s what it takes to answer the big questions of the front end.

When in doubt, answer the big questions at the expense of the details. And to stay on track, revisit and refine the learning objectives. And to improve confidence, show it to real customers.

And rinse and repeat, as needed.

Image credit – Jason Samfield

Working with uncertainty

Try – when you’re not sure what to do.

Try – when you’re not sure what to do.

Listen – when you want to learn.

Build – when you want to put flesh on the bones of your idea.

Think – when you want to make progress.

Show a customer – when you want to know what your idea is really worth.

Put it down – when you want your subconscious to solve a problem.

Define – when you want to solve.

Satisfy needs – when you want to sell products

Persevere – when the status quo kicks you in the shins.

Exercise – when you want set the conditions for great work.

Wait – when you want to run out of time and money.

Fear failure – when you want to block yourself from new work.

Fear success – when you want to stop innovation in its tracks.

Self-worth – when you want to overcome fear.

Sleep – when you want to be on your game.

Chance collision – when you want something interesting to work on.

Write – when you want to know what you really think.

Make a hand sketch – when you want to communicate your idea.

Ask for help – when you want to succeed.

Image credit – Daniel Dionne

The WHY and HOW of Innovation

Innovation is difficult because it demands new work. But, at a more basic level, it’s difficult because it requires an admission that the way you’ve done things is no longer viable. And, without public admission the old way won’t carry the day, innovation cannot move forward. After the admission there’s no innovation, but it’s one step closer.

Innovation is difficult because it demands new work. But, at a more basic level, it’s difficult because it requires an admission that the way you’ve done things is no longer viable. And, without public admission the old way won’t carry the day, innovation cannot move forward. After the admission there’s no innovation, but it’s one step closer.

After a public admission things must change, a cultural shift must happen for innovation to take hold. And for that, new governance processes are put in place, new processes are created to set new directions and new mechanisms are established to make sure the new work gets done. Those high-level processes are good, but at a more basic level, the objectives of those process areto choose new projects, manage new projects and allocate resources differently. That’s all that’s needed to start innovation work.

But how to choose projects to move the company toward innovation? What are the decision criteria? What is the system to collect the data needed for the decisions? All these questions must be answered and the answers are unique to each company. But for every company, everything starts with a top line growth objective, which narrows to an approach based on an industry, geography or product line, which then further necks down to a new set of projects. Still no innovation, but there are new projects to work on.

The objective of the new projects is to deliver new usefulness to the customer, which requires new technologies, new products and, possibly, new business models. And with all this newness comes increased uncertainty, and that’s the rub. The new uncertainty requires a different approach to project management, where the main focus moves from execution of standard tasks to fast learning loops. Still no innovation, but there’s recognition the projects must be run differently.

Resources must be allocated to new projects. To free up resources for the innovation work, traditional projects must be stopped so their resources can flow to the innovation work. (Innovation work cannot wait to hire a new set of innovation resources.) Stopping existing projects, especially pet projects, is a major organizational stumbling block, but can be overcome with a good process. And once resources are allocated to new projects, to make sure the resources remain allocated, a separate budget is created for the innovation work. (There’s no other way.) Still no innovation, but there are people to do the innovation work.

The only thing left to do is the hardest part – to start the innovation work itself. And to start, I recommend the IBE (Innovation Burst Event). The IBE starts with a customer need that is translated into a set of design challenges which are solved by a cross-functional team. In a two-day IBE, several novel concepts are created, each with a one page plan that defines next steps. At the report-out at the end of the second day, the leaders responsible for allocating the commercialization resources review the concepts and plans and decide on next steps. After the first IBE, innovation has started.

There’s a lot of work to help the organization understand why innovation must be done. And there’s a lot of work to get the organization ready to do innovation. Old habits must be changed and old recipes must be abandoned. And once the battle for hearts and minds is won, there’s an equal amount of work to teach the organization how to do the new innovation work.

It’s important for the organization to understand why innovation is needed, but no customer value is delivered and no increased sales are booked until the organization delivers a commercialized solution.

Some companies start innovation work without doing the work to help the organization understand why innovation work is needed. And some companies do a great job of communicating the need for innovation and putting in place the governance processes, but fail to train the organization on how to do the innovation work.

Truth is, you’ve got to do both. If you spend time to convince the organization why innovation is important, why not get some return from your investment and teach them how to do the work? And if you train the organization how to do innovation work, why not develop the up-front why so everyone rallies behind the work?

Why isn’t enough and how isn’t enough. Don’t do one without the other.

Image credit — Sam Ryan

Innovation is about good judgement.

It’s not the tools. Innovation is not hampered by a lack of tools (See The Innovator’s Toolkit for 50 great ones.), it’s hampered because people don’t know how to start. And it’s hampered because people don’t know how to choose the right tool for the job. How to start? It depends. If you have a technology and no market there are a set of tools to learn if there’s a market. Which tool is best? It depends on the context and learning objective. If you have a market and no technology there’s a different set of tools. Which tool is best? You guessed it. It depends on the work. And the antidote for ‘it depends’ is good judgement.

It’s not the tools. Innovation is not hampered by a lack of tools (See The Innovator’s Toolkit for 50 great ones.), it’s hampered because people don’t know how to start. And it’s hampered because people don’t know how to choose the right tool for the job. How to start? It depends. If you have a technology and no market there are a set of tools to learn if there’s a market. Which tool is best? It depends on the context and learning objective. If you have a market and no technology there’s a different set of tools. Which tool is best? You guessed it. It depends on the work. And the antidote for ‘it depends’ is good judgement.

It’s not the process. There are at least several hundred documented innovation processes. Which one is best? There isn’t a best one – there can be no best practice (or process) for work that hasn’t been done before. So how to choose among the good practices? It depends on the culture, depends on the resources, depends on company strengths. Really, it depends on good judgment exercised by the project leader and the people that do the work. Seasoned project leaders know the process is different every time because the context and work are different every time. And they do the work differently every time, even as standard work is thrust on them. With new work, good judgement eats standardization for lunch.

It’s not the organizational structure. Innovation is not limited by a lack of novel organizational structures. (For some of the best thinking, see Ralph Ohr’s writing.) For any and all organizational structures, innovation effectiveness is limited by people’s ability to ride the waves and swim against the organizational cross currents. In that way, innovation effectiveness is governed by their organizational good judgement.

Truth is, things have changed. Gone are the rigid, static processes. Gone are the fixed set of tools. Gone are the black-and-white, do-this-then-do-that prescriptive recipes. Going forward, static must become dynamic and rigid must become fluid. One-size-fits-all must evolve into adaptable. But, fortunately, gone are the illusions that the dominant player is too big to fail. And gone are the blinders that blocked us from taking the upstarts seriously.

This blog post was inspired by a recent blog post by Paul Hobcraft, a friend and grounded innovation professional. For a deeper perspective on the ever-increasing complexity and dynamic nature of innovation, his post is worth the read.

After I read Paul’s post, we talked about the import role judgement plays in innovation. Though good judgement is not usually called out as an important factor that governs innovation effectiveness, we think it’s vitally important. And, as the pressure increases to deliver tangible innovation results, its importance will increase.

Some open questions on judgement: How to help people use their judgement more effectively? How to help them use it sooner? How to judge if someone has the right level of good judgement?

Image credit – Michael Coghlan

Improving What Is and Creating What Isn’t

There are two domains – what is and what isn’t. We’re most comfortable in what is and we don’t know much about what isn’t. Neither domain is best and you can’t have one without the other. Sometimes it’s best to swim in what is and other times it’s better to splash around in what isn’t. Though we want them, there are no hard and fast rules when to swim and when to splash.

Improvement lives in the domain of what is. If you’re running a Six Sigma project, a lean project or a continuous improvement program you’re knee deep in what is. Measure, analyze, improve, and control what is. Walk out to the production floor, count the machines, people and defects, measure the cycle time and eliminate the wasteful activities. Define the current state and continually (and incrementally) improve what is. Clear, unambiguous, measurable, analytical, rational.

The close cousins creativity and innovation live in the domain of what isn’t. They don’t see what is, they only see gaps, gulfs and gullies. They are drawn to the black hole of what’s missing. They define things in terms of difference. They care about the negative, not the image. They live in the Bizarro world where strength is weakness and far less is better than less. Unclear, ambiguous, intuitive, irrational.

What is – productivity, utilization, standard work. What isn’t – imagination, unstructured time, daydreaming. Predictable – what is. Unknowable – what isn’t.

In the world of what is, it’s best to hire for experience. What worked last time will work this time. The knowledge of the past is all powerful. In the world of what isn’t, it’s best to hire young people that know more than you do. They know the latest technology you’ve never heard of and they know its limitations.

Improving what is pays the bills while creating what isn’t fumbles to find the future. But when what is runs out of gas, what isn’t rides to the rescue and refuels. Neither domain is better, and neither can survive without the other.

The magic question – what’s the best way to allocate resources between the domains? The unsatisfying answer – it depends. And the sextant to navigate the dependencies – good judgement.

Image credit – JD Hancock

Transcending Our Financial Accounting Systems

In business and in life, one of the biggest choices is what to do next. Sounds simple, but it’s not.

In business and in life, one of the biggest choices is what to do next. Sounds simple, but it’s not.

The decision has many facets and drives many questions, for example: Does it fit with core competence? Does it fit with the brand? How many will we sell? What will the market look like after it’s launched? Do we have what it takes to pull it off?

These questions then explode into a series of complex financial analyses like – return on investment, return on capital, return on net assets (and all its flavors) and all sorts of yet-to-be created return on this’s and that’s. This return business is all about the golden ratio – how much will we make relative to how much it costs. All the calculations, regardless of their name, are variations on this theme. And all suffer the same fundamental flaw – they are based on an artificial system of financial accounting.

To me, especially when working in new territory, we must transcend the self-made biases and limitations of GAAP and ask the bedrock question – Is it worth it?

In the house of cards of our financial accounting, worth equals dollars. Nothing more, nothing less. And this simplistic, formulaic characterization has devastating consequence. Worth is broader than profit, it’s nuanced, it’s philosophical, it’s about people, it’s about planet. Yet we let our accounting systems lead us around by the nose as if people don’t matter, like the planet doesn’t matter, like what we stand for doesn’t matter. Simply put, worth is not dollars.

The single-most troubling artifact of our accounting systems is its unnatural bias toward immediacy. How much will we make next year? How about next quarter? What will we spend next month? If we push out the expense by a month how much will we save? What will it do to this quarter’s stock price? It’s like the work has no validity unless the return on investment isn’t measured in days, weeks or months. It seems the only work that makes it through the financial analysis gauntlet is work that costs nothing and returns almost nothing. Under the thumb of financial accounting, projects are small in scope, smaller in resource demands and predictable in time. This is a recipe for minimalist improvement and incrementalism.

What about the people doing the work? Why aren’t we concerned they can’t pay their mortgages? Why do we think it’s okay to demand they work weekends? Why don’t we hold their insurance co-pays at reasonable levels? Why do we think it’s okay to slash our investment in their development? What about their self-worth? Just because we can’t measure it in a financial sense, don’t we think it’s a liability to foster disenchantment and disengagement? If we considered our people an asset in a financial accounting sense, wouldn’t we invest in them to protect their output? Why do we preventive maintenance on our machines but not our people?

When doing innovative work, our financial accounting systems fail us. These systems were designed in an era when it was best to increase the maturity of immature systems. But now that our systems are mature, and our objective is to obsolete them, our ancient financial accounting systems hinder more than help. The domains of reinvention and disruption are dominated by judgement, not rigid accounting rules. Innovation is the domain of incomplete data and uncertain outcomes and not the domain of debits and credits.

Profit is important, but profit is a result. Financial accounting doesn’t create profit, people create profit. And the currency of people are thoughts, feelings and judgement.

With innovation, it’s better to create the conditions so people believe in the project and are fully engaged in their work. With creativity, it’s better to have empowered people who will move mountains to do what must be done. With work that’s new, it’s better to trust people and empower them to use their best judgement.

Image credit – Jeremy Tarling

With innovation, it depends.

By definition, when the work is new there is uncertainty. And uncertainty can be stressful. But, instead of getting yourself all bound up, accept it. More than that, relish in it. Wear it as a badge of honor. Not everyone gets the chance to work on something new – only the best do. And, because you’ve been asked to do work with a strong tenor of uncertainty, someone thinks you’re the best.

By definition, when the work is new there is uncertainty. And uncertainty can be stressful. But, instead of getting yourself all bound up, accept it. More than that, relish in it. Wear it as a badge of honor. Not everyone gets the chance to work on something new – only the best do. And, because you’ve been asked to do work with a strong tenor of uncertainty, someone thinks you’re the best.

But uncertainty is an unknown quantity, and our systems have been designed to reject it, not swim in it. When companies want to get serious they drive toward a culture of accountability and the new work gets the back seat. Accountability is mis-mapped to predictability, successful results and on time delivery. Accountability, as we’ve mapped it, is the mortal enemy of new work. When you’re working on a project with a strong element of uncertainty, the only certainty is the task you have in front of you. There’s no certainty on how the task will turn out, rather, there’s only the simple certainty of the task.

With work with low uncertainty there are three year plans, launch timelines and predictable sales figures. Task one is well-defined and there’s a linear flow of standard work right behind it – task two through twenty-two are dialed in. But when working with uncertainty, the task at hand is all there is. You don’t know the next task. When someone asks what’s next the only thing you can say is “it depends.” And that’s difficult in a culture of traditional accountability.

An “it depends” Gannt chart is an oxymoron, but with uncertainty step two is defined by step one. If A, then B. But if the wheels fall off, I’m not sure what we’ll do next. The only thing worse than an “it depends” Gantt chart is an “I’m not sure” Gannt chart. But with uncertainty, you can be sure you won’t be sure. With uncertainty, traditional project planning goes out the window, and “it depends” project planning is the only way.

With uncertainty, traditional project planning is replaced by a clear distillation of the problem that must be solved. Instead of a set of well-defined tasks, ask for a block diagram that defines the problem that must be solved. And when there’s clarity and agreement on the problem that must be solved, the supporting tasks can be well-defined. Step one – make a prototype like this and test it like that. Step two – it depends on how step one turns out. If it goes like this then we’ll do that. If it does that, we’ll do the other. And if it does neither, we’re not sure what we’ll do. You don’t have to like it, but that’s the way it is.

With uncertainty, the project plan isn’t the most important thing. What’s most important is relentless effort to define the system as it is. Here’s what the system is doing, here’s how we’d like it to behave and, based on our mechanism-based theory, here’s the prototype we’re going to build and here’s how we’re going to test it. What are we going to do next? It depends.

What’s next? It depends. What resources do you need? It depends. When will you be done? It depends.

Innovation is, by definition, work that is new. And, innovation, by definition, is uncertain. And that’s why with innovation, it depends. And that’s why innovation is difficult.

And that’s why you’ve got to choose wisely when you choose the people that do your innovation work.

Image credit – Sara Biljana Gaon (off)

Sometimes things need to get worse before they can get better.

All the scary words are grounded in change. Innovation, by definition, is about change. When something is innovative it’s novel, useful and successful. Novel is another word for different and different means change. That’s why innovation is scary. And that’s why radical innovation is scarier.

All the scary words are grounded in change. Innovation, by definition, is about change. When something is innovative it’s novel, useful and successful. Novel is another word for different and different means change. That’s why innovation is scary. And that’s why radical innovation is scarier.

Continuous improvement, where everything old is buffed and polished into something new, is about change. When people have followed the same process for fifteen years and then it’s improved, people get scared. In their minds improved isn’t improved, improved is different. And different means change. Continuous improvement is especially scary because it makes processes more productive and frees up people to do other things, unless, of course, there are no other things to do. And when that happens their jobs go away. Every continuous improvement expert knows when the first person loses their job due to process improvement the program is dead in the saddle, yet it happens. And that’s scary on a number of fronts.

And then there’s disruption. While there’s disagreement on what it actually is, there is vicious agreement that after a disruption the campus will be unrecognizable. And unrecognizable things are unrecognizable because they are different from previous experience. And different means change. With mortal innovation there are some limits, but with disruption everything is fair game. With disruption everything can change, including the venerable, yet decrepit, business model. With self-disruption, the very thing responsible for success is made to go away by the people that that built it. And that’s scary. And when a company is disrupted from the outside it can die. And, thankfully, that’s scary.

But change isn’t scary. Thinking about change is scary.

There’s one condition where change is guaranteed – when the pain of the current situation is stronger than the fear of changing it. One source of pain could be from a realization the ship will run aground if a new course isn’t taken. When pain of the immanent shipwreck (caused by fear) overpowers the fear of uncharted waters, the captain readily pulls hard to starboard. And when the crew realizes it’s sink or swim, they swim.

Change doesn’t happen before it’s time. And before things get bad enough, it’s not time.

When the cruise ship is chugging along in fair seas, change won’t happen. Right before the fuel runs out and the generators quit, it’s all you can eat and margaritas for everyone. And right after, when the air conditioning kicks out and the ice cream melts, it’s bedlam. But bedlam is not the best way to go. No sense waiting until the fuel’s gone to make change. Maybe someone should keep an eye the fuel gauge and let the captain know when there’s only a quarter tank. That way there’s some time to point the ship toward the closest port.

There’s no reason to wait for a mutiny to turn the ship, but sometimes an almost mutiny is just the thing.

As a captain, it’s difficult to let things get worse so they can get better. But if there’s insufficient emotional energy to power change, things must get worse. The best captains run close to the reef and scrape the hull. The buffet tables shimmy, the smoked salmon fouls the deck and the liquor bottles rattle. And when done well, there’s a deep groan from the bowels of the ship that makes it clear this is no drill. And if there’s a loud call for all hands on deck and a cry for bilge pumps at the ready, all the better.

To pull hard in a new direction, sometimes the crew needs help to see things as they are, not as they were.

Image credit – Francis Bijl

The Cycle of Success

There’s a huge amount of energy required to help an organization do new work.

There’s a huge amount of energy required to help an organization do new work.

At every turn the antibodies of the organization reject new ideas. And it’s no surprise. The organization was created to do more of what it did last time. Once there’s success the organization forms structures to make sure it happens again. Resources migrate to the successful work and walls form around them to prevent doing yet-to-be-successful work. This all makes sense while the top line is growing faster than the artificially set growth goal. More resources applied to the successful leads to a steeper growth rate. Plenty of work and plenty of profit. No need for new ideas. Everyone’s happy.

When growth rate of the successful company slows below arbitrary goal, the organization is slow to recognize it and slower to acknowledge it and even slower to assign true root cause. Instead, the organization doubles down on what it knows. More resources are applied, efficiency improvements are put in place, and clearer metrics are put in place to improve accountability. Everyone works harder and works more hours and the growth rate increases a bit. Success. Except the success was too costly. Though total success increased (growth), success per dollar actually decreased. Still no need for new ideas. Everyone’s happy, but more tired.

And then growth turns to contraction. With no more resources move to the successful work, accountability measures increase to unreasonable levels and people work beyond their level of effectiveness. But this time growth doesn’t come. And because people are too focused on doing more of what used to work, new ideas are rejected. When a new idea is proposed, it goes something like this “We don’t need new ideas, we need growth. Now, get out of my way. I’m too busy for your heretical ideas.” There’s no growth and no tolerance for new ideas. No one is happy.

And then a new idea that had been flying under the radar generates a little growth. Not a lot, but enough to get noticed. And when the old antibodies recognize the new ideas and try to reject it, they cannot. It’s too late. The new idea has developed a protective layer of growth and has become a resistant strain. One new idea has been tolerated. Most are unhappy because there’s only one small pocket of growth and a few are happy because there’s one small pocket of growth.

It’s difficult to get the first new idea to become successful, but it’s worth the effort. Successful new ideas help each other and multiply. The first one breaks trail for the second one and the second one bolsters the third. And as these new ideas become more successful something special happens. Where they were resistant to the antibodies they become stronger than the antibodies and eat them.

Growth starts to grow and success builds on success. And the cycle begins again.

Image credit – johnmccombs

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski