Archive for the ‘Uncertainty’ Category

Three Things for the New Year

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Some things will be the same and some will be different. The trouble is that we won’t know which is which until we do. We can speculate on how it will be different, but the Universe doesn’t care about our speculation. Sure, it can be helpful to think about how things may go, but as long as we hold on to the may-ness of our speculations. And we don’t know when we’ll know. We’ll know when we know, but no sooner. Even when the Operating Plan declares the hardest of hard dates, the Universe sets the learning schedule on its own terms, and it doesn’t care about our arbitrary timelines.

What to do?

Step 1. Try three new things. Choose things that are interesting and try them. Try to try them in parallel as they may interact and inform each other. Before you start, define what success looks like and what you’ll do if they’re successful and if they’re not. Defining the follow-on actions will help you keep the scope small. For things that work out, you’ll struggle to allocate resources for the next stages, so start small. And if things don’t work out, you’ll want to say that the projects consumed little resources and learned a lot. Keep things small. And if that doesn’t work, keep them smaller.

Step 2. Rinse and repeat.

I wish you a happy and safe New Year. And thanks for reading.

Mike

“three” by Travelways.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Your core business is your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

Your core business, the long-standing business that has made you what you are, is both your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

Your core business, the long-standing business that has made you what you are, is both your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

The Core generates the revenue, but it also starves fledgling businesses so they never make it off the ground.

There’s a certainty with the Core because it builds on success, but its success sets the certainty threshold too high for new businesses. And due to the relatively high level of uncertainty of the new business (as compared to the Core) the company can’t find the gumption to make the critical investments needed to reach orbit.

The Core has generated profits over the decades and those profits have been used to create the critical infrastructure that makes its success easier to achieve. The internal startup can’t use the Core’s infrastructure because the Core doesn’t share. And the Core has the power to block all others from taking advantage of the infrastructure it created.

The Core has grown revenue year-on-year and has used that revenue to build out specialized support teams that keep the flywheel moving. And because the Core paid for and shaped the teams, their support fits the Core like a glove. A new offering with a new value proposition and new business model cannot use the specialized support teams effectively because the new offering needs otherly-specialized support and because the Core doesn’t share.

The Core pays the bills, and new ventures create bills that the Core doesn’t like to pay.

If the internal startup has to compete with the Core for funding, the internal startup will fail.

If the new venture has to generate profits similar to the Core, the venture will be a misadventure.

If the new offering has to compete with the Core for sales and marketing support, don’t bother.

If the fledgling business’s metrics are assessed like the Core’s metrics, it won’t fly, it will flounder.

If you try to run a new business from within the Core, the Core will eat it.

To work effectively with the Core, borrow its resources, forget how it does the work, and run away.

To protect your new ventures from the Core, physically separate them from the Core.

To protect your new businesses from the Core, create a separate budget that the Core cannot reach.

To protect your internal startup from the Core, make sure it needs nothing from the Core.

To accelerate the growth of the fledgling business, make it safe to violate the Core’s first principles.

To bolster the capability of your new business, move resources from the Core to the new business.

To de-risk the internal startup, move functional support resources from the Core to the startup.

To fund your new ventures, tax the Core. It’s the only way.

“Core Memory” by JD Hancock is licensed under CC BY 2.0

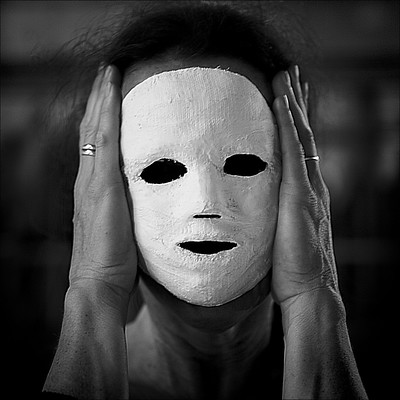

Everyone is doing their best, even though it might not look that way.

In these trying times when stress is high, supply chains are empty, and the pandemic is still alive and well, here’s a mantra to hold onto:

In these trying times when stress is high, supply chains are empty, and the pandemic is still alive and well, here’s a mantra to hold onto:

Everyone is doing their best, even though it might not look that way.

When restaurants are only open four days a week because they have no one to take the orders and clean the dishes, they are trying their best. Sure, you can’t go there for dinner on those off-days. And, sure, it cramps your style. And, sure, it looks like they’re doing it just to piss you off. But they are trying their best. They want to be open. They want to serve you dinner and take your money. It may not look like it, but they are doing their best. How might you hold onto that reality? How might you engage your best self and respond accordingly?

The situation at restaurants is one of many where people are trying their best but environmental realities have caused their best to be less than it was. Car dealers want to sell cars, but there are fewer of them to sell. The prices are higher, the choices are fewer, and the lead times are longer. The salespeople aren’t out to get you; there’s simply more demand than cars. If you want a car, try to buy one. But if you can’t or you don’t like the price, what does it say about you if you get angry at the salesperson? It may not look like it, but they are trying their best. How might you hold onto that? What would it take for you to behave like they are trying their best?

Plumbers and electricians have more work than they can handle. If they don’t answer their phone, or don’t respond quickly, or respond with a quote that’s higher than you think reasonable, don’t take it personally. They are doing their best. Plumbers actually like to trade their time for your money and it’s the same with electricians. But, there are simply more pipes to be worked on than there are plumbers to work them. And there’s more wiring to do than there are electricians to do work. Their best isn’t as good as it was, but it’s still their best. You can get angry, but that won’t get your leaks fixed or your new electrical outlets installed. How might you hold onto the fact that they are doing their best? And, how might you engage your best self to respond with kindness and understanding?

And it’s the same situation at work. Everyone is trying their best, though it may look that way. Our families or parents are struggling; our kids are having a difficult time; we can’t find plumbers; we can’t hire electricians; we cannot afford new cars prices; there are no cars to buy; and the restaurants are closed. This is crazy enough on its own, but all those outside stressors are sitting on top of a collection of work-related stressors. There are many vacant positions so there are fewer people to do the work; competitors have upped the pressure; under the banner of doing more with less, more projects have been added, even though there are fewer people; and profitability goals have been turned up to eleven.

How might we hold onto the reality that our personal lives are stressful and, though we are trying harder than ever, our best CANNOT be good as it used to be? And how might we hold onto the reality that with such stress at home, we are giving our all but we have LESS to give.

Let’s help each other hold onto the mantra:

Everyone is doing their best, even though it might not look that way.

“the mask” by wolfgangfoto is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

A Leading Indicator of Personal Growth — Fear

When was the last time you did something that scared you? And a more important follow-on question: How did you push through your fear and turn it into action?

When was the last time you did something that scared you? And a more important follow-on question: How did you push through your fear and turn it into action?

Fear is real. Our bodies make it, but it’s real. And the feelings we create around fear are real, and so are the inhibitions we wrap around those feelings. But because we have the authority to make the fear, create the feelings, and wrap the inhibitions, we also have the authority to unmake, un-create, and unwrap.

Fear can feel strong. Whether it’s tightness in the gut, coldness in the chest, or lushness in the face, the physical manifestations in the body are recognizable and powerful. The sensations around fear are strong enough to stop us in our tracks. And in the wild of a bygone time, that was fear’s job – to stop us from making a mistake that would kill us. And though we no longer venture into the wild, fear responds to family dynamics, social situations, interactions at work, as if we still live in the wild.

To dampen the impact of our bodies’ fear response, the first step is to learn to recognize the physical sensations of fear for what they are – sensations we make when new situations arise. To do that, feel the sensations, acknowledge your body made them, and look for the novelty, or divergence from our expectations, that the sensations stand for. In that way, you can move from paralysis to analysis. You can move from fear as a blocker to fear as a leading indicator of personal growth.

Fear is powerful, and it knows how to create bodily sensations that scare us. But, that’s the chink in the armor that fear doesn’t want us to know. Fear is afraid to be called by name, so it generates these scary sensations so it can go on controlling our lives as it sees fit. So, next time you feel the sensations of fear in your body, welcome fear warmly and call it by name. Say something like, “Hello Fear. Thank you for visiting with me. I’d like to get to know you better. Can you stay for a coffee?”

You might find that Fear will engage in a discussion with you and apologize for causing you trouble. Fear may confess that it doesn’t like how it treats you and acknowledge that it doesn’t know how to change its ways. Or, it may become afraid and squirt more fear sensations into your body. If that happens, tell Fear that you understand it’s just doing what it evolved to do, and repeat your offer to sit with it and learn more about its ways.

The objective of calling Fear by name is to give you a process to feel and validate the sensations and then calm yourself by looking deeply at the novelty of the situation. By looking squarely into Fear’s eyes, it will slowly evaporate to reveal the nugget of novelty it was cloaking. And with the novelty in your sights, you can look deeply at this new situation (or context or interpersonal dynamic) and understand it for what it is. Without Fear’s distracting sensations, you will be pleasantly surprised with your ability to see the situation for what it is and take skillful action.

So, when Fear comes, feel the sensations. Don’t push them away. Instead, call Fear by name. Invite Fear to tell its story, and get to know it. You may find that accepting Fear for what it is can help you grow your relationship with Fear into a partnership where you help each other grow.

“tractor pull 02 – Arnegard ND – 2013-07-04” by Tim Evanson is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

How To See What’s Missing

With one eye open and the other closed, you have no depth perception. With two eyes open, you see in three dimensions. This ability to see in three dimensions is possible because each eye sees from a unique perspective. The brain knits together the two unique perspectives so you can see the world as it is. Or, as your brain thinks it is, at least.

With one eye open and the other closed, you have no depth perception. With two eyes open, you see in three dimensions. This ability to see in three dimensions is possible because each eye sees from a unique perspective. The brain knits together the two unique perspectives so you can see the world as it is. Or, as your brain thinks it is, at least.

And the same can be said for an organization. When everyone sees things from a single perspective, the organization has no depth perception. But with at least two perspectives, the organization can better see things as they are. The problem is we’re not taught to see from unique perspectives.

With most presentations, the material is delivered from a single perspective with the intention of helping everyone see from that singular perspective. Because there’s no depth to the presentation, it looks the same whether you look at it with one eye or two. But with some training, you can learn how to see depth even when it has purposely been scraped away.

And it’s the same with reports, proposals, and plans. They are usually written from a single perspective with the objective of helping everyone reach a single conclusion. But with some practice, you can learn to see what’s missing to better see things as they are.

When you see what’s missing, you see things in stereo vision.

Here are some tips to help you see what’s missing. Try them out next time you watch a presentation or read a report, proposal, or plan.

When you see a WHAT, look for the missing WHY on the top and HOW on the bottom. Often, at least one slice of bread is missing from the why-what-how sandwich.

When you see a HOW, look for the missing WHO and WHEN. Usually, the bread or meat is missing from the how-who-when sandwich.

Here’s a rule to live by: Without finishing there can be no starting.

When you see a long list of new projects, tasks, or initiatives that will start next year, look for the missing list of activities that would have to stop in order for the new ones to start.

When you see lots of starting, you’ll see a lot of missing finishing.

When you see a proposal to demonstrate something for the first time or an initial pilot, look for the missing resources for the “then what” work. After the prototype is successful, then what? After the pilot is successful, then what? Look for the missing “then what” resources needed to scale the work. It won’t be there.

When you see a plan that requires new capabilities, look for the missing training plan that must be completed before the new work can be done well. And look for the missing budget that won’t be used to pay for the training plan that won’t happen.

When you see an increased output from a system, look for the missing investment needed to make it happen, the missing lead time to get approval for the missing investment, and the missing lead time to put things in place in time to achieve the increased output that won’t be realized.

When you see a completion date, look for the missing breakdown of the work content that wasn’t used to arbitrarily set the completion date that won’t be met.

When you see a cost reduction goal, look for the missing resources that won’t be freed up from other projects to do the cost reduction work that won’t get done.

It’s difficult to see what’s missing. I hope you find these tips helpful.

“missing pieces” by LeaESQUE is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Certainty or novelty – it’s your choice.

When you follow the best practice, by definition your work is not new. New work is never done the same way twice. That’s why it’s called new.

When you follow the best practice, by definition your work is not new. New work is never done the same way twice. That’s why it’s called new.

Best practices are for old work. Usually, it’s work that was successful last time. But just as you can never step into the same stream twice, when you repeat a successful recipe it’s not the same recipe. Almost everything is different from last time. The economy is different, the competitors are different, the customers are in a different phase of their lives, the political climate is different, interest rates are different, laws are different, tariffs are different, the technology is different, and the people doing the work are different. Just because work was successful last time doesn’t mean that the old work done in a new context will be successful next time. The most important property of old work is the certainty that it will run out of gas.

When someone asks you to follow the best practice, they prioritize certainty over novelty. And because the context is different, that certainty is misplaced.

We have a funny relationship with certainty. At every turn, we try to increase certainty by doing what we did last time. But the only thing certain with that strategy is that it will run out of gas. Yet, frantically waving the flag of certainty, we continue to double down on what we did last time. When we demand certainty, we demand old work. As a company, you can have too much “certainty.”

When you flog the teams because they have too much uncertainty, you flog out all the novelty.

What if you start the design review with the question “What’s novel about this project?” And when the team says there’s nothing novel, what if you say “Well, go back to the drawing board and come back with some novelty.”? If you seek out novelty instead of squelching it, you’ll get more novelty. That’s a rule, though not limited to novelty.

A bias toward best practices is a bias toward old work. And the belief underpinning those biases is the belief that the Universe is static. And the one thing the Universe doesn’t like to be called is static. The Universe prides itself on its dynamic character and unpredictable nature. And the Universe isn’t above using karma to punish those who call it names.

“Stonecold certainty” by philwirks is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

The Illusion of Control

Unhappy: When you want things to be different than they are.

Unhappy: When you want things to be different than they are.

Happy: When you accept things as they are.

Sad: When you fixate on times when things turned out differently than you wanted.

Neutral: When you know you have little control over how things will turn out.

Anxious: When you fixate on times when things might turn out differently than you want.

Stressed: When you think you have control over how things will turn out.

Relaxed: When you know you don’t have control over how things will turn out.

Agitated: When you live in the future.

Calm: When you live in the present.

Sad: When you live in the past.

Angry: When you expect a just world, but it isn’t.

Neutral: When you expect that it could be a just world, but likely isn’t.

Happy: When you know it doesn’t matter if the world is just.

Angry: When others don’t meet your expectations.

Neutral: When you know your expectations are about you.

Happy: When you have no expectations.

Timid: When you think people will judge you negatively.

Neutral: When you think people may judge you negatively or positively.

Happy: When you know what people think about you is none of your business.

Distracted: When you live in the past or future.

Focused: When you live in the now.

Afraid of change: When you think all things are static.

Accepting change: When you know all things are dynamic.

Intimidated: When you think you don’t meet someone’s expectations.

Confident: When you know you did your best.

Uncomfortable: When you want things to be different than they are.

Comfortable: When you know the Universe doesn’t care what you think.

“Space – Antennae Galaxies” by Trodel is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The Dark Underbelly of Success

Best practice – a tired recipe you recycle because you think the world is static.

Best practice – a tired recipe you recycle because you think the world is static.

Emergent practice – a new way to work created from whole cloth because the context is new.

Worst practice – a best practice applied to a world that has changed around you.

Novel practice– work that recognizes the world is a different place but is dismissed out-of-hand because everyone wants to live in the comfortable past.

Continuous improvement – when you try to put a shine on a tired, old process that worked ten years ago.

Discontinuous improvement – work that is disrespectful to the Status Quo and hurts people’s feelings.

Grow the core – when you do what you did in 2010 because you don’t know what else to do.

Obsolete your best work – when you do work that makes it clear to your customers that they should not have purchased your most successful product.

Reduce operating expense – what you do when you don’t know how to grow the top line and want to eliminate the flexibility to respond to an uncertain future.

Grow the top line – when you launch a new product that causes your customers to happily throw away the product they just bought from you.

A PowerPoint slide deck that defines your strategic plan – an electronic work product that distracts you from the reality of an ever-changing future.

A new product that is radically better than your last one – what you should create instead of a PowerPoint slide deck that defines your strategic plan.

MBA – a university degree that gives you a pedigree so companies hire you.

Ph.D. – a university degree that teaches you to learn, but takes too long.

Return On Investment (ROI) – a calculation that scuttles new work that would reinvent your business.

Imagination – thinking that will help you navigate an uncertain future, but is knee-capped by the ROI calculation.

Standard work – a process you used last time and will use next time because, again, you think the world is static.

Judgment – thinking that creates a whole new business trajectory to address an uncertain future but can get you fired if you use it.

A sustainable competitive advantage – a relic of a slow-moving world.

Continual change – the only way to deal with an ever-accelerating future.

Success – profits from work done by people who retired from your company some time ago.

Success – the thing that blocks you from working on the unproven.

Success – what pays the bills.

Success – what jeopardizes your ability to pay the bills in five years.

Success – why people think old practices are best practices.

Success – why new work is so difficult to do.

Success – why continuous improvement carries the day.

Success – why discontinuous improvement threatens.

Success – the mother of complacency.

“dark underbelly” by JoeBenjamin is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The Innovation Mantra

We have an immense distaste for uncertainty. And, as a result, we create for ourselves a radical and unskillful overestimation of our ability to control things. Our distaste of uncertainty is really a manifestation of our fear of death. When we experience and acknowledge uncertainty, it’s an oblique reminder that we will die. And that’s why talk ourselves into the belief we can control thing we really cannot. It’s a defense mechanism that creates distance between ourselves and from feeling our fear of death. And it’s the obliquity that makes it easier to overestimate our ability to control our environment. Without the obliquity, it’s clear we can’t control our environment, the very thing we wake up to every morning, and it’s clear we can’t control much. And if we can’t control much, we can’t control our aging and our ultimate end. And this is why we reject uncertainty at all costs.

We have an immense distaste for uncertainty. And, as a result, we create for ourselves a radical and unskillful overestimation of our ability to control things. Our distaste of uncertainty is really a manifestation of our fear of death. When we experience and acknowledge uncertainty, it’s an oblique reminder that we will die. And that’s why talk ourselves into the belief we can control thing we really cannot. It’s a defense mechanism that creates distance between ourselves and from feeling our fear of death. And it’s the obliquity that makes it easier to overestimate our ability to control our environment. Without the obliquity, it’s clear we can’t control our environment, the very thing we wake up to every morning, and it’s clear we can’t control much. And if we can’t control much, we can’t control our aging and our ultimate end. And this is why we reject uncertainty at all costs.

Predictable, controllable, repeatable, measurable – overt rejections of uncertainty. Six Sigma – Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control – overt rejection of uncertainty. Standard work – rejection of uncertainty. Don’t change the business model – a rejection of uncertainty. A rejection of novelty is a rejection of uncertainty. And that’s why we don’t like novelty. It scares us deeply. And it scares us because it reminds us that everything changes, including our skin, joints, and hairline. And that’s why it’s so challenging to do innovation.

Innovation reminds us of our death and that’s why it’s difficult? Really? Yes.

Six Sigma is comforting because its programmatic illusion of control lets us forget about our death? Yes.

The aging business model reminds us of our death and that’s why we won’t let it go? Yes.

That’s crazy! Yes, but at the deepest level, I think it’s true.

I understand if you disagree with my rationale. And I understand if you think my thinking is morbid. If that’s the case, I suggest you write down why you think it’s so incredibly difficult to create a new business model, to do novel work, or to obsolete your best work. I’ll stop for a minute to give you time to grab a pen and paper. Okay, now put your pen to paper and write down why doing innovation (doing novel work) is so difficult. Now, ask yourself why that is. And do that three more times. Where did you end up? What’s the fundamental reason why doing new work (and the uncertainty that comes with it) is so difficult to do?

To be clear, I’m not advocating that you tell everyone that innovation is difficult because it reminds them that they’ll die. I explained my rationale to give you an idea of the magnitude of the level of fear around uncertainty so that, when someone is scared to death of novelty, you might help them navigate their fear.

Trying something new doesn’t invalidate what you did over the last decade to grow your business, nor will it replace it immediately, if it all. Maybe the new work will add to what you’ve done over the last decade. Maybe the new work will amplify what’s made you successful. Maybe the new work will slowly and effectively migrate your business to greener pastures. And maybe it won’t work at all. Or, maybe your customers will make it work and bury you and your business.

With innovation, start small. That way the threat is smaller. Run small experiments and share the results, especially the bad results. That way you demonstrate that unanticipated results don’t kill you and, when you share them, you demonstrate that you’re not afraid of uncertainty. Try many things in parallel to demonstrate that it’s okay that everything doesn’t turn out well and you’re okay with it. And when someone asks what you’ll do next, tell them “I don’t know because it depends on how the next experiment turns out.”

When you’re asked when you’ll be done with an innovation project, tell them “I don’t know because the work has never been done before.” And if they say you must give them a completion date, tell them “If you must have a completion date, you do the project.”

When you’re running multiple experiments in parallel and you’re asked what you’ll do next, tell them you’ll do “more of what works and less of what doesn’t.” And if they say “that’s not acceptable”, then tell them “Well, then you run the project.”

We don’t have nearly as much control as our minds want to us believe, but that’s okay as long as we behave like we know it’s true. Uncertainty is uncomfortable, but that’s not a bad thing. In fact, I think it’s a good thing.

If people aren’t afraid, there can be no uncertainty. And if there’s no uncertainty, there can be no novelty. And if there’s no novelty, there can be no innovation. If people aren’t afraid, you’re doing it wrong.

As a leader, tell them you’re afraid but you’re going to do it anyway.

As a leader, tell your team that it’s natural to be afraid and their fear is a leading indicator of innovation.

As a leader, tell them there’s one thing you’re certain about – that innovation is uncertain.

And when things get difficult, repeat the Innovation Mantra: Be afraid and do it anyway.

“Mantra” by j / f / photos is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Regardless of the question, trust is the answer.

If you want to make a difference, build trust.

If you want to make a difference, build trust.

If you want to build trust, do a project together.

If you want to build more trust, help the team do work they think is impossible.

If you want to build more trust, contribute to the project in the background.

If you want to build more trust, actively give credit to others.

If you want to build more trust, deny your involvement.

If you want to create change, build trust.

If you want to build trust, be patient.

If you want to build more trust, be more patient.

If you want to build more trust, check your ego at the door so you can be even more patient.

If you want to have influence, build trust.

If you want to build trust, do something for others.

If you want to build more trust, do something for others that keeps them out of trouble.

If you want to build more trust, do something for others that comes at your expense.

If you want to build more trust, do it all behind the scenes.

If you want to build more trust, plead ignorance.

If you want the next project to be successful, build trust.

If you want to build trust, deliver what you promise.

If you want to build more trust, deliver more than you promise.

If you want to build more trust, deliver more than you promise and give the credit to others.

If you want deep friendships, build trust.

If you want to build trust, give reinforcing feedback.

If you want to build more trust, give reinforcing and correcting feedback in equal amounts.

If you want to build trust, give reinforcing feedback in public and correcting feedback in private.

If you want your work to have meaning, build trust.

“[1823] Netted Pug (Eupithecia venosata)” by Bennyboymothman is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Goals, goals, goals.

All goals are arbitrary, but some are more arbitrary than others.

All goals are arbitrary, but some are more arbitrary than others.

When your company treats goals like they’re not arbitrary, welcome to the US industrial complex.

What happens if you meet your year-end goals in June? Can you take off the rest of the year?

What happens if at year-end you meet only your mid-year goals? Can you retroactively declare your goals unreasonable?

What happens if at the start of the year you declare your year-end goals are unreasonable? Can you really know they’re unreasonable?

You can’t know a project’s completion date before the project is defined. That’s a rule.

Why does the strategic planning process demand due dates for projects that are yet to be defined?

The ideal future state may be ideal, but it will never be real.

When the work hasn’t been done before, you can’t know when you’ll be done.

When you don’t know when the work will be done, any due date will do.

A project’s completion date should be governed by the work content, not someone’s year-end bonus.

Resources and progress are joined at the hip. You can’t have one without the other.

If you are responsible for the work, you should be responsible for setting the completion date.

Goals are real, but they’re not really real.

“Arbitrary limitations II” by Marcin Wichary is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski