Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

Universal Truths

When things don’t go as planned, recognize the Universe doesn’t care about your plan.

When things don’t go as planned, recognize the Universe doesn’t care about your plan.

When the going gets tough, the Universe is telling you something. You just don’t know what it’s telling you.

When in doubt, do the next right thing. That’s how the Universe rolls.

If you don’t like how it’s going, change your situation or change your expectations. Those are the two options sanctioned by the Universe.

If something bad happens, don’t take it personally. The Universe doesn’t know your name.

If you catch yourself taking your plan seriously, don’t. The Universe frowns on seriousness.

Don’t spend time creating a grand plan. The Universe isn’t big on grand plans.

If your plan requires the tide to stay away, make a different one. The Universe never forgets to tell the tide to come in.

If you find yourself chasing the Idealized Future State, stop. The Universe has disdain for the ideal.

If something good happens, don’t take it personally. The Universe doesn’t know your name.

When you don’t know the answer, that’s the Universe telling you you may be onto something.

When you have all the right answers, that’s the Universe telling you you’re not asking the right questions.

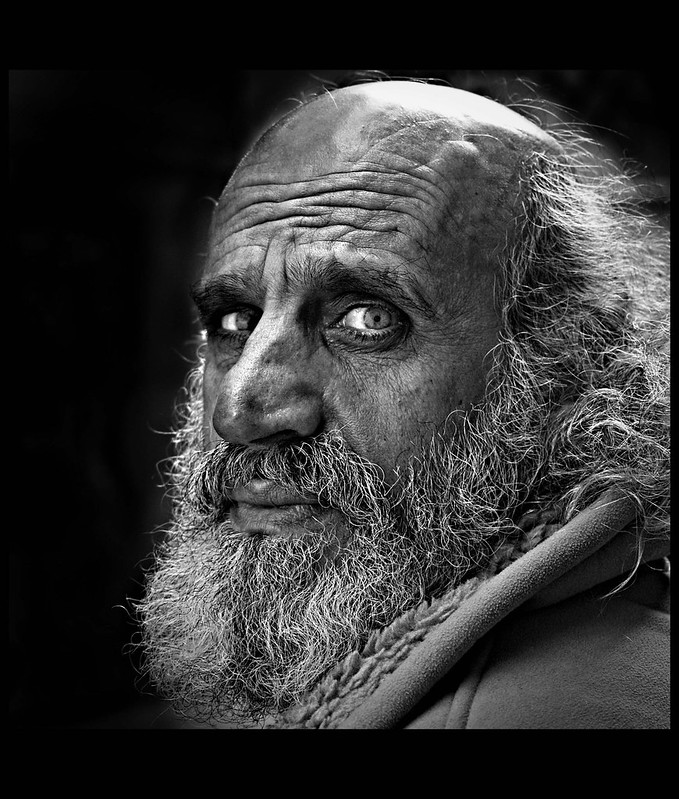

Image credit — Giuseppe Donatiello

The Frustration Equation

For right frustration to emerge, you need an accurate understanding of how things are, a desire for them to be different, and a recognition you can’t remedy the situation.

For right frustration to emerge, you need an accurate understanding of how things are, a desire for them to be different, and a recognition you can’t remedy the situation.

The emergence of your desire for things to be different starts with knowing how things are. And to see things as they are, you’ve got to be in the right condition – well-rested, unstressed, and sitting in the present moment. When you’re tired, stressed, or sitting in the past or future you can’t pay attention. And when you don’t pay attention, you miss details or context and see something that isn’t. Or, if you’re tired or stressed you can have clear eyes and a muddy interpretation. Either way, you’re off to a bad start because your desire for things to be different is wrongly informed. Sure, your misunderstanding can lead to a desire for things to be different, but your desire is founded on the wrong understanding. If you want your frustration to be right frustration, seeing things as they are is the foundational step. But it’s not yet a desire for things to be different.

Your desire for things to be different is a subtraction of sorts – when how things are minus how you want them to be equals something other than zero. (See Eq. 1) Your brain-body uses that delta to create a desire for things to be different. If how things are is equal to how you want them to be, the difference is zero (no delta) and there is no forcing function for your desire. In that way, if you always want things to be as they are, there can be no desire for difference and frustration cannot emerge. But frustration can emerge if you know how you want things to be and you recognize they’re not that way.

Eq. 1 Forcing Function for Desire (FFD) = (how things are) – (how you want them to be)

There is a more complete variant of the above equation where FFD is non-zero (there’s a difference between how things are and how you want them) yet frustration cannot emerge. It’s called the “I don’t care enough” variant. (See Eq. 2) With this variant, you recognize how things are, you know how you want them to be, but you don’t care enough to be frustrated.

Eq. 2 FFD = [(how things are) – (how you want them to be)] * (Care Factor)

When you don’t care, your Care Factor (CF) = 0. And when the non-zero delta is multiplied by a CF of zero, FFD is zero. This means there is no forcing function for desire and frustration cannot emerge. But this is not a good place to be. Sure, frustration cannot emerge, but when you don’t care there is no forcing function for change. Yes, you see things aren’t as you want, but you go along for the ride and don’t do anything about it. I think that’s sad. And I think that’s bad for business. I’d rather have frustration.

Eq. 2 can be used by Human Resources as an Occom’s Razor of sorts. If someone is frustrated, their CF is non-zero and they care.

Now the third factor required for frustration to emerge – a recognition you can’t do anything about the mismatch between how things are and how you want them. If you don’t recognize you can’t do anything to equalize how things are and how you want them, there can be no frustration. Think – ignorance is bliss. If you think you can do something to make how things are the same as how you want them, there is no frustration. Because it’s important to you (CF is non-zero), you will devote energy to bringing the two sides together and there will be no frustration. But when there’s a mismatch between how things are and how you want them, you care about making that mismatch go away, and you recognize you can’t do anything to eliminate the mismatch, frustration emerges.

What does all this say about people who display frustration? Do you want people that know how to see things as they are? Do you want people who can imagine how things can be different? Do you want people who understand the difference between what they can change and what they cannot? Do you want people who care enough to be frustrated?

Image credit — Atilla Kefeli

The Importance of Moving From Telling to Asking

Tell me what you want done, but don’t tell me how. You’ve got to leave something for me.

Tell me what you want done, but don’t tell me how. You’ve got to leave something for me.

Better yet, ask me to help you with a problem and let me solve it. I prefer asking over telling.

Better still, explain the situation and ask me what I think. We can then discuss why I see it the way I do and we can create an approach.

Even better, ask me to assess the situation and create a proposal.

Better still, ask me to assess the situation, create a project plan, and run the project.

If you come up with a solution but no definition of the problem, I will ask you to define the problem.

If you come up with a solution and a definition of the problem, I will ask you to explain why it’s the right solution.

If you come up with a problem, a solution, and an analysis that justifies the solution, I will ask why you need me.

If you know what you want to do, don’t withhold information and make me guess.

If you know what you want to do, ask me to help and I will help you with your plan.

If you know what you want to do and want to improve your plan, ask me how to make your plan better.

If you want your plan to become our plan, bring me in from the start and ask me what I think we should do.

Image credit — x1klima

How It Goes With Demos

Demoing something for the first time is difficult, but doing it for the second time is easy. And when you demo a new solution the first time, it (and you) will be misunderstood.

Demoing something for the first time is difficult, but doing it for the second time is easy. And when you demo a new solution the first time, it (and you) will be misunderstood.

What is the value of this new thing? This is a good question because it makes clear they don’t understand it. After all, they’ve never seen it before. And it’s even better when they don’t know what to call it. Keep going!

Why did you do this? This is a good question because it makes clear they see the demo as a deviation from historically significant lines of success. And since the lines of success are long in the tooth, it’s good they see it as a violation of what worked in the olden days. Keep going!

Whose idea was this? This is code: “This crazy thing is a waste of time and we could have applied resources to that tired old recipe we’ve been flogging for a decade now.” It means they recognize the prototype will be received differently by the customer. They don’t think it will be received well, but they know the customer will think it’s different. Keep going!

Who approved this work? This is code: “I want to make this go away and I hope my boss’s boss doesn’t know about it so I can scuttle the project.” But not to worry because the demo is so good it cannot be dismissed, ignored, or scuttled. Keep going!

Can you do another demo for my boss? This one’s easy. They like it and want to increase the chances they’ll be able to work on it. That’s a nice change!

Why didn’t you do this, that, or the other? They recognized the significance, they understood the limitations, and they asked a question about how to make it better. Things are looking up!

How much did the hardware cost? They see the new customer value and want to understand if the cost is low enough to commercialize with a good profit margin. There’s no stopping this thing!

Can we take it to the next tradeshow and show it to customers? Success!

Image credit — Bennilover

Respect what cannot be changed.

If you try to change what you cannot, your trying will not bring about change. But it will bring about 100% frustration, 100% dissatisfaction, 100% missed expectations, 0% progress, and, maybe, 0% employment.

If you try to change what you cannot, your trying will not bring about change. But it will bring about 100% frustration, 100% dissatisfaction, 100% missed expectations, 0% progress, and, maybe, 0% employment.

Here’s a rule: If success demands you must change what you cannot, you will be unsuccessful.

If you try to change something you cannot change but someone else can, you will be unsuccessful unless you ask them for help. That part is clear. But here’s the tricky part – unless you know you cannot change it and they can, you won’t know to ask them.

If you know enough to ask the higher power for help and they say no but you try to change it anyway, you will be unsuccessful. I don’t think that needed to be said, but I thought it important to overcommunicate to keep you safe.

Here’s the money question – How do you know if you can change it?

Here’s another rule: If you want to know if you can change something, ask.

If the knowledgeable people on the project say they cannot change it, believe them. Make a record of the assessment for future escalation, define the consequences, and rescope the project accordingly. Next, search the organization (hint – look north) for someone with more authority and ask them if they can grant the authority to change it. If they say no, document their decision and stick with the rescoped project plan. If they say yes, document their decision and revert to the original project plan.

If you do one thing tomorrow, ask your project team if success demands they change something they cannot. I surely hope their answer is no.

Image credit — zczillinger

Resource Allocation IS Strategy

In business, we have vision statements, mission statements, strategic plans, strategic initiatives, and operating plans. And every day there are there are countless decisions to make. But, in the end, it all comes down to one thing – how we allocate our resources. Whether it’s hiring people, training them, buying capital, or funding projects, all strategic decisions come back to resource allocation. Said more strongly, resource allocation is strategy.

In business, we have vision statements, mission statements, strategic plans, strategic initiatives, and operating plans. And every day there are there are countless decisions to make. But, in the end, it all comes down to one thing – how we allocate our resources. Whether it’s hiring people, training them, buying capital, or funding projects, all strategic decisions come back to resource allocation. Said more strongly, resource allocation is strategy.

Take a look back at last year. Where did you allocate your capital dollars? Which teams got it and which did not? Your capital allocation defined your priorities. The most important businesses got more capital. More to the point – the allocated capital defined their importance. Which projects were fully staffed and fully budgeted? Those that were resourced more heavily were more important to your strategy, which is why they were resourced that way. Which businesses hired people and which did not? The hiring occurred where it fulfilled the strategy. Which teams received most of the training budget? Those teams were strategically important. Prioritization in the form of resource allocation.

Repeat the process for this year’s operating plan. Where is the capital allocated? Where is the hiring allocated? Where are the projects fully staffed and budgeted? Regardless of the mission statements, this year’s strategy is defined by where the resources are allocated. Full stop.

Repeat the process for your forward-looking strategic plans. Where are the resources allocated? Which teams get more? Which get fewer? Answer these questions and you’ll have an operational definition of your company’s forward-looking strategy.

To know if the new strategy is different from the old one, look at the budgets. Do they show a change in resource allocation? Will old projects stop so new ones can start? Do the new projects serve new customers and new value propositions? Same old projects, same old customers, same old value propositions, same old strategy.

To determine if there’s a new strategy, look for changes in capital allocation. If the same teams are allocated more of the same capital, it’s likely the strategy is also the same. Will one team get more capital while the others get less? Well, it’s likely a new strategy is starting to take shape.

Look for a change in hiring. Fewer hires like last year and more of a new flavor probably indicate a change in strategy. And if people flow from one team to another, that’s the same as one team getting new hires and the other team losing them. That type of change in resource allocation is an indicator of a strategic change.

If the resource allocation differs from the strategic plan, believe the resource allocation. And if the resource allocation is the same as last year, so is the strategy. And if there is talk of changing resource allocation but no actual change, then there is no change in strategy.

Image credit – Scouse Smurf

Some Ifs and Thens To Get You Through Your Day

If you didn’t get what you wanted, why not try wanting what you got?

If you didn’t get what you wanted, why not try wanting what you got?

If the timing isn’t right, what can you change so it is right?

If it could get you in trouble, might you be on to something?

If it’s impossible, don’t bother.

If it’s easy, let someone else do it.

If there’s no possibility of bad things, there’s no possibility of magic.

If you need trust but have not yet secured it, declare failure and do something else.

If there is no progress, don’t push. Move the blocking agent out of the way.

If you don’t know where the cost is, you can’t design it out.

If the timing isn’t right, why didn’t you do it sooner?

If the project went flawlessly, you didn’t try to do anything meaningful.

If you know some people won’t like it, isn’t that reason enough to do it?

If it’s almost impossible, give it a go.

If it’s easy, teach someone else to do it.

If you don’t know where the waste is, you can’t get rid of it.

If you don’t need trust, it’s the perfect time to build it.

If you try the hardest thing first and it doesn’t work, at least you avoid wasting time on the easy stuff.

If you don’t know the number of parts in your product, you have too many.

If the product came out perfectly, you took too long.

If you don’t give it a go, how can you know it’s impossible?

If trust is in short supply, supply it.

If it’s easy, do something else.

If forgiveness is so much better than permission, why do we like to do things under the radar?

If bad things didn’t happen, try harder next time.

Image credit — Gabriel Caparó

Two Sides of the Same Coin

Praise is powerful, but not when you don’t give it.

Praise is powerful, but not when you don’t give it.

People learn from mistakes, but not when they don’t make them.

Wonderful solutions are wonderful, but not if there are no problems.

Novelty is good, but not if you do what you did last time.

Disagreement creates deeper understanding, but not if there’s 100% agreement.

Consensus is safe, but not when it’s time for original thought.

Progress is made through decisions, but not if you don’t make them.

It’s skillful to constrain the design space, but not if it doesn’t contain the solution.

Trust is powerful, but not before you build it.

A mantra: Praise people in public.

If you want people to learn, let them make mistakes.

Wonderful problems breed wonderful solutions.

If you want novelty, do new things.

There can be too little disagreement.

Consensus can be dangerous.

When it’s decision time, make one.

Make the design space as small as it can be, but no smaller.

Build trust before you need it.

Image credit – Ralf St.

Projects, Products, People, and Problems

With projects, there is no partial credit. They’re done or they’re not.

With projects, there is no partial credit. They’re done or they’re not.

Solve the toughest problems first. When do you want to learn the problem is not solvable?

Sometimes slower is faster.

Problems aren’t problems until you realize you have them. Before that, they’re problematic.

If you can’t put it on one page, you don’t understand it. Or, it’s complex.

Take small bites. And if that doesn’t work, take smaller bites.

To get more projects done, do fewer of them.

Say no.

Stop starting and start finishing.

Effectiveness over efficiency. It’s no good to do the wrong thing efficiently.

Function first, no exceptions. It doesn’t matter if it’s cheaper to build if it doesn’t work.

No sizzle, no sale.

And customers are the ones who decide if the sizzle is sufficient.

Solve a customer’s problem before solving your own.

Design it, break it, and fix it until you run out of time. Then launch it.

Make the old one better than the new one.

Test the old one to set the goal. Test the new one the same way to make sure it’s better.

Obsolete your best work before someone else does.

People grow when you create the conditions for their growth.

If you tell people what to do and how to do it, you’ll get to eat your lunch by yourself every day.

Give people the tools, time, training, and a teacher. And get out of the way.

If you’ve done it before, teach someone else to do it.

Done right, mentoring is good for the mentor, the mentee, and the bottom line.

When in doubt, help people.

Trust is all-powerful.

Whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Image credit — Hartwig HKD

When in doubt, look inside.

When we quiet our minds, we can hear our bodies’ old stories in the form of our thoughts.

When we quiet our minds, we can hear our bodies’ old stories in the form of our thoughts.

Pay attention to our bodies and we understand our minds.

Our bodies give answers before our minds know the questions.

If we don’t understand our actions, it’s because our bodies called the ball.

The physical sensations in our bodies are trailheads for self-understanding.

Our bodies’ old stories govern our future actions.

If a cat sits on a hot stove, that cat won’t sit on a hot stove again. That cat won’t sit on a cold stove either. Our bodies are just like the cat.

Our mouths sing the songs but our bodies write the sheet music.

Our bodies make decisions and then our minds declare ownership.

When we’re reactive, it’s because our bodies recognize the context and trigger the old response.

When a smell triggers a strong memory, that’s our body at work.

Bessel was right. The body keeps the score.

Image credit — Raul AB

Time is not coming back.

How much time do you spend on things you want to do?

How much time do you spend on things you don’t want to do?

How much time do you have left to change that?

If you’re spending time on things you don’t like, maybe it’s because you don’t have any better options. Sometimes life is like that.

But maybe there’s another reason you’re spending time on things you don’t like.

If you’re afraid to work on things you like, create the smallest possible project and try it in private.

If that doesn’t work, try a smaller project.

If you don’t know the ins and outs of the thing you like, give it a try on a small scale. Learn through trying.

If you don’t have a lot of money to do the thing you like, define the narrowest slice and give it a go.

If you could stop on one thing so you could start another, what are those two things? Write them down.

And start small. And start now.

Image credit — Pablo Monteagudo

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski