Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

How To Create The Conditions For Good Things To Happen

Reduce the energy cost of virtue so it’s less than the energy cost of sin. (Dave Snowden)

Reduce the energy cost of virtue so it’s less than the energy cost of sin. (Dave Snowden)

Said another way – make it easy to do the right thing.

Don’t push through. Move obstacles out of the way.

Don’t tell people about their problem. Ask people about their problem.

Try small experiments and do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

Don’t tell people they have a problem. Volunteer to help them.

Instead of Ready, Fire, Aim, try Ready, Aim, Fire.

Before trying to improve things, define the system as it is.

When two competing theories cause disagreement, agree to try both.

Slow down to go faster.

Say no so you can say yes.

Give praise in public and give criticism in private.

Say nothing negative unless you’ve exhausted all other possibilities.

Build trust BEFORE you need it.

These are good ways to create the conditions for good things to happen.

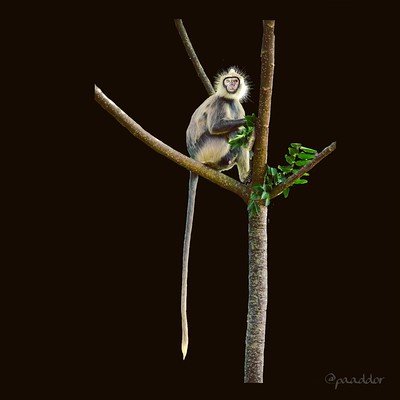

Image credit — Peter Addor – The monkey that makes a monkey of us.

Elevate the Holiday Season by Understanding WHY

What is this all about?

What is this all about?

What is the reason you do what you do? What’s your WHY behind the WHAT?

When you don’t do what you said you’d do, what’s the reason? And what does that say about you?

If the reason is right, I think it can be okay NOT to do something you said you’d do. But I try to set a high bar on this one.

When things get tough, what gets you to push through? For me, it’s about doing something for the people I care about.

When things go well, what causes you to give credit to others? For me, it’s about building momentum and helping people understand the special things they did to make it happen.

Why do you show up? When you ask yourself, do you have an answer?

How do you show up for? And the more difficult question – WHY?

When is it okay to be compliant in a minimum energy way? And how do you decide that’s okay?

When do you decide to apply your whole self to something that others think is misaligned with the charter? I think this says a lot about a person.

What are you willing to do even though you know you’ll be judged negatively for doing it? I’m often unsure why to do it, but I’m sure it’s the right thing to do. I don’t know what that says about me, but I’m okay with it.

To me, the WHY is far more important than the WHAT. The WHY explains things. The WHY tells the story. The WHY gives guidance on what will happen next time.

When you do something happen that’s out of the ordinary (a WHAT), I suggest you try to figure out the WHY. I have found that some seemingly nonsensical WHATs make a lot of sense when you understand the WHY underpinning the WHAT.

And during this holiday season, may you give people the benefit of the doubt on their WHATs, and take the time to understand their highly personal WHYs. That can make for a happier holiday season for all.

Image credit — Christopher Henry

Thankfulness Is A Choice

Some have more than you, some have less. Can you be thankful?

Some have more than you, some have less. Can you be thankful?

Things will go well, and things will go poorly. Will you be thankful?

Some will support you, and others will diminish. Can you be thankful?

Truth will be told, and so will lies. Will you be thankful?

You can prevent some problems, but others you cannot. Can you be thankful?

Some of your hypotheses will be validated, and others will be invalidated. Will you be thankful?

Sometimes you will be supported, and other times criticized. Can you be thankful?

You will be healthy, and you will be sick. Will you be thankful?

You will get old. Can you be thankful?

Sometimes you will be calm, and other times anxious. But can you be thankful?

Sometimes you will agree with family, and sometimes you will disagree. Can you be thankful?

You will have everything, then it will all go away? Can you be thankful?

Things will be better and worse. Will you be thankful?

There will be success and failure. Can you be thankful?

You will be happy and sad. Will you be thankful?

Some family members will live close to you, and others will live far away. Can you be thankful?

Some friends will support you, and others will bail. Will you be thankful?

Sometimes you will rise to the occasion, and other times you will bail. Can you be thankful?

You will be understood and misunderstood. Will you be thankful?

Thankfulness is a choice. What will you choose?

Image credit — Cindi Albright

Skillful Awareness

When do you bring your whole self to the endeavor? You can’t do this every time, and that’s okay.

When do you bring your whole self to the endeavor? You can’t do this every time, and that’s okay.

What are the conditions that cause you to engage fully? Full engagement is expensive. Spend wisely.

What about the situation causes you to run toward the problem? Solve the right ones, but leave some for the rest of us.

Which situations bring out the best in you? Sometimes your best isn’t very good, and that’s okay.

When do you block yourself from jumping into the adventure? All adventures aren’t worth the jump. Block wisely.

What are the conditions that cause you to phone it in? Sometimes the best choice is a phone call.

What about the situation causes you to give others a chance to run toward the problem? There’s nothing wrong with that. Save yourself for the right problems.

Which situations demand that you protect your best self? It’s okay to protect yourself and live to fight another day. That’s why they make bulletproof vests.

Sometimes we get caught up in the heat of battle and bring our energy in an unskillful way. And sometimes we are lulled into inaction when bringing our energy is the more skillful action.

I have found that maintaining awareness helps me allocate my energy wisely and skillfully.

May you be aware of your surroundings and your self.

Image credit – Jan Mosimann

Resting Is Natural

When the ocean gets tired from holding its water up to make high tide, it lets go and relaxes into low tide. The ocean takes direction from the moon who knows it can’t always be high tide. This is The Way.

When the earth gets tired from heating up the northern hemisphere it wobbles on its axis and relaxes its northern territories into cooler weather. And the reduced energy demand in the north frees up energy for the earth to focus on heating up its southern hemisphere. Taking direction from the sun, the earth knows it cannot always be hot in the north or the south. And it know it doesn’t have enough energy to make it hot in the north and south at the same time. And it knows it can’t be lazy all year and let it be cold in both hemisheres year round. It’s natural for winter to follow summer and for the hemispheres to be out of phase. The earth and sun know this. It’s natural for them.

Bears have their fun in spring summer and fall. They are all-in on eating, taking care of young bears, and making new ones. After three seasons of fun and games, bears know they need to hunker down and rest for the winter. That is how it is with bears and how it will always be. It is natural bear behavior. And it works.

When you work out hard, your body knows it needs to rest the next day. It knows it needs to recover from the elevated stress of the workout so it gives you feedback that it’s important to do less the following day. There’s nothing wrong with that. In fact, there’s everything right with that. It’s natural and it works.

And there are natural rest cycles at work, After a full week of planning meetings, people need to downshift into work that is less taxing and gives their bodies time to process the plans. This is not weakness, it’s natural.

And there are even natural hibernation cycles at work in the form of vacations and holidays. Like with bears, our bodies need (and deserve) deep rest. And just bears don’t check their email when hibernating, neither should we. Taking time for deep rest is not irresponsible or wasteful, it’s natural

Without a trough there can be no crest. And without rest there can be no high performance. This, too, is natural.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

996 or Bust

996 is all the rage. You work 9 am to 9 pm, 6 days a week. Startups are doing it. Might non-startups start doing it?

996 is all the rage. You work 9 am to 9 pm, 6 days a week. Startups are doing it. Might non-startups start doing it?

Productivity is important and competition is severe. And I’m all for working hard, but I don’t think the 996 schedule is the most effective way to achieve productivity goals, at least not for all jobs.

My decision-making capabilities diminish when I am tired, and I would be tired if I worked a 996 schedule. My interpersonal and organizational effectiveness would suffer if I worked 996. My planning skills would degrade if I worked 996. My family life would suffer if I worked 996. And my physical and mental health would degrade..

In my work, I make many decisions, I create conditions for teams and organizations to do new work, and I contemplate the future and figure out what to do next. Maybe I should be able to do this work well with a 996 schedule. But I know myself, and I know I would be far less effective working 996. Maybe my work is uniquely unfit for 996? Maybe I am uniquely unfit for 996?

Some questions for you:

- How many hours can you concentrate in one day?

- How about the second day?

- If you worked a 996 schedule, would you get more done?

- How many weeks could you work 996 before the wheels fall off?

The startup pace is rapid. Progress must be made before the money runs out. At these early stages, when a company’s existence depends on hitting the super agressive timelines, I think 996 is especially attractive to startup companies The potential financial upside is large which may make for a fair trade – more hours for the chance of outsized compensation.

But what if an established company sets extremely tight timelines and offers remarkable compensation if those timelines are met? Does 996 become viable? What if an established company sets startup-like timelines but without added compensation? Would 996 be viable in that case?

Some countries and regions work a 996 schedule as a matter of course – no limited to startups and (likely) no special compensation. And it seems to work for them, at least from the outside. And 996 may be an important supporting element of their impressively low costs, high quality, and speed.

If those countries amd regions can sustain their 996 culture, and I think they will, it will create pressure on other countries to adopt a similar approach to avoid falling further behind.

I’m unsure what broad adoption of 996 would mean for the world.

Image credit — Evan

Getting To Know Your Projects

Good new product development projects deliver value to customers. Bad ones create value for your company, not for customers. Can you discern between custom value and company value? What do you do when there’s an abundance of company value and a shortfall of customer value? Do you run the project anyway or pull the emergency brake as soon as possible?

Customers decide if the new product has value. That’s a rule. No one likes that rule, but it’s still a rule. The loudest voice doesn’t decide; it only drowns out the customer’s voice.

Having too many projects is worse than having too few. With too few, you finish projects quickly because shared resources are not overutilized. With too many, shared resources are overbooked, their service times blossom, and projects are late. Would you rather start two projects and finish two or start seven and finish none? That’s how it goes with projects.

Three enemies of new product development: waiting, waiting, waiting. Waiting that extends the critical path is the worst flavor of all. Can you tell when the waiting is on the critical path? If you calculate the cost of delay, it’s possible to spend money to eliminate waiting that’s on the critical path and make more money for your company. H/T to Don Rienertsen.

For projects, effectiveness is more important than efficiency. Yes, you read that correctly. Would you rather efficiently run the wrong project (low effectiveness) or run the right project inefficiently? Do you spend more mental energy on efficiency or effectiveness? (You don’t have to say your answer out loud.)

I think post-mortems of projects have no value. The next project will be different, and the learning will not be applicable or forgotten altogether. However, I think pre-mortems are powerful and can improve the effectiveness of a project BEFORE it is started. I suggest you try it on your next project.

Strategy is realized through projects. Projects generate growth. Cost savings come to life through projects. I think building a deeper understanding of your projects is the most important thing you can do.

Image credit — Mike Keeling (one too many head on collisions)

Degrees of Not Knowing

You know you know, but you don’t.

You know you know, but you don’t.

You think you know, but you don’t.

You’re pretty sure you don’t know.

You know you don’t know, you think it’s not a problem that you don’t, but it is a problem.

You know you don’t know, you think it’s a problem that you don’t, but it isn’t a problem.

You don’t know, you don’t know that you don’t need to know yet, and you try.

You don’t know, you know you don’t need to know yet, and you wait.

You don’t know, you can’t know, you don’t know you can’t, and you try.

You don’t know, you can’t know, you know you can’t, and you wait.

Some skills you may want to develop….

To know when you know and when you don’t, ask yourself if you know and listen to the response.

To know if it’s a problem that you don’t know or if it isn’t, ask yourself, “Is it a problem that I don’t know?” If it isn’t, let it go. If it is, get after it.

To know if it’s not time to know or if it is, ask yourself, “Do I have to know this right now?” If it’s not time, wait. If it is time, let the learning begin. Trying to know before you need to is a big waste of time.

To know if you can’t know or if you can, ask yourself, “Can I know this?” and listen for the answer. Trying to learn when you can’t is the biggest waste of time.

Image credit — Dennis Skley

What To Do When You Don’t Know What To Do

Create something that isn’t.

Create something that isn’t.

Build something that turns ‘didn’t’ into ‘does’.

Work on your cants.

Help people.

Make a prototype.

Use all the pieces, but use them in different ways.

Make it worse and then do the opposite. (H/T to VF)

Finish one before starting another.

Turn a ‘must not’ into a ‘hey, watch this!’

Do less with far less (post 1, post 2).

Bundle the old and new items together, and vice versa.

See cannot as a call to arms.

Say no to good projects and yes to the amazing ones.

Use half the pieces.

See quitting as fast finishing.

Ask for help.

Repeat.

Image credit Victor Sassen (confusion)

Seeing Growth A Different Way

Growing a company is challenging. Here are some common difficulties and associated approaches to improve effectiveness.

Growing a company is challenging. Here are some common difficulties and associated approaches to improve effectiveness.

No – The way we work is artisanal.

Yes – We know how to do the work innately.

It’s perfectly fine if the knowledge lives in the people.

Would you rather the knowledge resides in the people, or not know at all?

You know how to do the work. Celebrate that.

No – We don’t know how to scale.

Yes – We know how to do the work, and that’s the most difficult part.

It doesn’t make sense to scale before you’ve done it for the first time.

Socks then shoes, not shoes then socks.

If you can’t do it once, you can’t scale it. That’s a rule.

Give yourselves a break. You can learn how to scale it up.

No – We don’t know how to create the right organizational structure.

Yes – We get the work done, despite our informal structure.

Your team grew up together, and they know how to work together.

Imagine how good you’ll be with a little organizational structure!

There is no “right” organizational structure. Add what you need where you need it.

Don’t be so hard on yourselves. Remember, you’re getting the work done.

No – We don’t have formal production lines.

Yes – Our volumes are such that it’s best to keep the machines in functional clusters.

It’s not time for you to have production lines. You’re doing it right.

When production volume increases, it will be time for production lines.

Go get the business so you can justify the production lines.

No – We have too many projects. It was easier when we had a couple of small projects.

Yes – We have a ton of projects that could take off!

Celebrate the upside. This is what growth feels like.

When the projects hit big, you’ll have the cash for the people and resources you need.

Would you rather the projects take off or fall flat?

Be afraid, celebrate the upside, and go get the projects.

No – We need everything.

Yes – Our people, processes, and systems are young AND we’re getting it done!

Assess the work, define what you need, take the right first bite, and see how it goes.

Reassess the work, define the next right bite, put it in place, and see how it goes.

Repeat.

This is The Way.

Attitude matters. Language matters. Approach matters. People matter.

Image credit — Eric Huybrechts (Temple of Janus)

Do More Than Keep The Score

Sometimes when I have a good idea, my body recognizes it before my mind does. I believe my body has been doing this since I was young, but only over the last five years have I developed sufficient body awareness to recognize the sensation my body generates. And now that I know the sensation is a signal, I know my body knows more than I do.

Sometimes when I have a good idea, my body recognizes it before my mind does. I believe my body has been doing this since I was young, but only over the last five years have I developed sufficient body awareness to recognize the sensation my body generates. And now that I know the sensation is a signal, I know my body knows more than I do.

My body’s signaling system is usually triggered during a conversation with someone I trust. While they are speaking to me, one or two of their words help my body flip the “knowing switch” and send its signal. Sometimes I stop listening and wait for the idea to come to my awareness. Sometimes I say out loud, “My body thinks there’s something important in what you said.” Sometimes the signal and idea come as a pair, and I tell my friend about the idea after they finish their sentence. All this takes some time for my coworkers and friends to understand and become comfortable.

My body can also send signals when it recognizes wrong paths or approaches that will cause conflict or confusion. It’s a colder sensation than the one described above, and the coldness distinguishes it as a signal of potential wrongness, conflict, or confusion. Like above, it’s usually triggered during a conversation where a coworker’s words help my body flip its knowing switch and send the cold sensation. Sometimes I stop listening and wait for the knowing to arrive. Sometimes I acknowledge I just received a knowing signal. And sometimes I tell my friend about the knowing as soon as there’s an opening. This, too, takes time for others to understand and become comfortable.

For my body to be able to do this for me, it must be well-rested, well-exercised, and grounded. To do this, my body must be standing on emotional bedrock.

I think I’m more effective because I can connect with my body’s signals. I can become aware of better ideas, I can become aware of skillful approaches, and I can become aware of ways to protect my friends from conflict and confusion.

Bessel van der Kolk says The Body Keeps The Score, and I agree. And with deep calm and awareness, I think the body can do much more.

Image credit — darkday

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski