Archive for the ‘Manufacturing Competitiveness’ Category

You might be a superhero if…

- Using just dirt, rocks, and sticks, you can bring to life a product that makes life better for society.

- Using just your mind, you can radically simplify the factory by changing the product itself.

- Using your analytical skills, you can increase product function in ways that reinvent your industry.

- Using your knowledge of physics, you can solve a longstanding manufacturing problem by making a product insensitive to variation.

- Using your knowledge of Design for Manufacturing and Assembly, you can reduce product cost by 50%.

- Using your knowledge of materials, you can eliminate a fundamental factory bottleneck by changing what the product is made from.

- Using your curiosity and creativity, you can invent and commercialize a product that creates a new industry.

- Using your superpowers, you think you can fix a country’s economy one company at a time.

How To Accelerate Engineers Into Social Media

Engineers fear social media, but shouldn’t. Our fear comes from lack of knowledge around information flow. Because we don’t understand how information flow works, we stay away. But our fear is misplaced – with social media information flow is controllable.

Engineers fear social media, but shouldn’t. Our fear comes from lack of knowledge around information flow. Because we don’t understand how information flow works, we stay away. But our fear is misplaced – with social media information flow is controllable.

For engineers, one-way communication is the best way to start. Engineers should turn on the information tap and let information flow to them. Let the learning begin.

At first, stay away from FaceBook – it’s the most social (non-work feel), least structured, and most difficult to understand – at least to me.

To start, I suggest LinkedIn – it’s the least social (most work-like) and highly controllable. It’s simple to start – create an account, populate your “resume stuff” (as little as you like) and add some connections (people you know and trust). You now have a professional network who can see your resume stuff and they can see yours. But no one else can, unless you let them. Now the fun part – find and join a working group in your interest area. A working group is group of like-minded people who create work-related discussions on a specific topic. Mine is called Systematic DFMA Deployment. You can search for a group, join (some require permission from the organizer), and start reading the discussions. The focused nature of the groups is comforting and you can read discussions without sharing any personal information. To start two-way communication, you can comment on a discussion.

After LinkedIn, engineers should try Twitter. Tweets (sounds funny, doesn’t it?) are sentences (text only) that are limited to 140 characters. With Twitter, one-way communication is the way to start – no need to share information. Just create an account and you’re ready to learn. With LinkedIn it’s about working groups, and with Twitter it’s about hashtags (#). Hashtags create focus with Twitter and make it searchable. For example, if the tweet creator uses #DFMA in the sentences, you can find it. Search for #DFMA and you’ll find tweets (sub-140 character sentences) related to design for manufacturing and assembly. When you find a hashtag of interest, monitor those tweets. (You can automate hashtag searches – HootSuite – but that’s for later). And when you find someone who consistently creates great content, you can follow them. Once followed, all their tweets are sent to your Twitter account (Twitter feed). To start two-way communication you can retweet (resend a tweet you like), send a direct message to someone (like a short email), or create your own tweet.

Twitter’s format comforts me – short, dense bursts of sentences and no more. Long tweets are not possible. But a tweet can contain a link to a website which points to a specific page on the web. To me it’s a great combination – short sentences that precisely point to the web.

With engineers and social media, the goal is to converge on collaboration. Ultimately, engineers move from one-way communication to two-way communication, and then to collaboration. Collaboration on LinkedIn and Twitter allows engineers to learn from (and interact with) the world’s best subject matter experts. Let me say that again – with LinkedIn and Twitter, engineers get the latest technical data, analyses, and tools from the best people in the world. And it’s all for free.

For engineers, social and media are the wrong words. For engineers, the right words are – controlled, focused, work-related information flow. And when engineers get comfortable with information flow, they’ll converge on collaboration. And with collaboration, engineers will learn from each other, help each other, innovate and, even, create personal relationships with each other.

Companies still look at social media as a waste of work time, and that’s especially true when it comes to their engineers. But that’s old thinking. More bluntly, that’s dangerous thinking. When their engineers use social media, companies will develop better products and technologies and commercialize them faster.

Plain and simple, companies that accelerate their engineers into social media will win.

On Independence

Independence for a country is about choice. A country wants to be able to make choices to better itself, to control its own destiny. A country wants to feel like it has freedom to do what it thinks is right. Hopefully, a country thinks it’s a good to provide for its citizens in a long term sense. We can disagree what is best, but a good country makes an explicit choice about what it think is right and takes responsibility for its choices. For a country, the choices should be grounded in the long term.

Independence for a country is about choice. A country wants to be able to make choices to better itself, to control its own destiny. A country wants to feel like it has freedom to do what it thinks is right. Hopefully, a country thinks it’s a good to provide for its citizens in a long term sense. We can disagree what is best, but a good country makes an explicit choice about what it think is right and takes responsibility for its choices. For a country, the choices should be grounded in the long term.

Independence for a company is about choice. Like a country, a company wants control over its own destiny. A company wants to feel like it has freedom to do what’s right. A company wants to decide what’s right and wants the ability to act accordingly. There are lots of management theories on what’s right, but the company wants to be able to choose. Like it or not, the company will be accountable for its choices, as measured by stock price or profit.

And with children, independence is about choice. Children, too, want control over their own destiny, but they score low on the responsibility scale. And that’s why children earn responsibility over time – get a little, don’t get hurt, and get a little more. They don’t know what’s good for them, but don’t let that get in the way of wanting control over their own destiny. That’s why parents exist.

Independence is about the ability to choose. But there’s a catch. With independence comes responsibility – responsibility for the choice. With children, there’s insufficient responsibility because they just don’t care. And with employees in a company, there’s insufficient responsibility for another reason – fear of failure. I’m not sure about countries.

Independence is a two way street – choice and responsibility. And independence is bound by constraints. (There are unalienable rights, but unconstrained independence isn’t one of them.) For more independence, push hard on constraints; for more independence, take responsibility; for more independence, make more choices (and own the consequences).

Happy Independence Day.

Small Is Good, And Powerful

If lean has taught us anything, it’s smaller is better. Smaller machines, smaller factories, smaller teams, smaller everything.

If lean has taught us anything, it’s smaller is better. Smaller machines, smaller factories, smaller teams, smaller everything.

The famous Speaker of the House, Tip O’Neill, said all politics are local. He meant all action happens at the lowest levels (in the districts and neighborhoods), where everyone knows everyone, where the issues are well understood, and the fundamentals are not just talked about, they’re lived. It’s the same with manufacturing. But I’m not talking about local in the geography sense; I’m talking about the neighborhood sense. When manufacturing is neighborhood-local, it’s small, tight, focused and knowledgeable.

We mistakenly think about manufacturing strictly as the process of making things—it’s far more. In the broadest sense, manufacturing is everything: innovation, design, making and service. It’s this broad-sense manufacturing that will deliver the next economic revolution.

Previously, I described how big companies break themselves into smaller operating units. They recognize lean favors small, and they break themselves up for competitive advantage. They want to become a collective of small companies with the upside of small without of the downside of big. Yet with small companies, there’s an urge to be big.

Lean says smaller is better and more profitable. Lean says small companies have an advantage because they’re already small. Lean says small companies should stay small (neighborhood small) and be more of what they are.

Small companies have a size advantage. Their smaller scope improves focus and alignment. It’s easier to define the mission, communicate it, and work toward it. It’s easier to mobilize the neighborhood. It’s clearer when things go off track and easier to get things back on track. At the lowest level, smaller companies zero in on problems and fix them. At the highest, they align themselves with their mission. These are important advantages, but not the most important.

The real advantage is deep process knowledge. Smaller companies have less breadth and more depth, which allows them to focus energy on the work and develop deep process knowledge. Many large manufacturers have lost process knowledge over the years. Small companies tend to develop and retain more of it. We’ve forgotten the value of deep process knowledge, but as companies look for competitive advantage, its stock is rising.

Lean wants small companies to build on that strength. To take it to the next level, lean wants companies to think about manufacturing in the more-than-making sense and use that deep process knowledge to influence the product itself. Lean wants suppliers to inject their process knowledge into their customers’ product development process to radically reduce material cost and help the product sprint through the factory.

The ultimate advantage of deep process knowledge is realized when small companies use it to design products. It’s realized when people who know the process fundamentals work respectfully with their neighbors who design the product. The result is deeper process knowledge and a far more profitable product. Big companies like to work with smaller companies who can design and make.

Tip O’Neill and lean agree. All manufacturing is local. And this local nature drives a focus on the fundamentals and details. Being neighborhood-local is easier for small companies because their scope is smaller, which helps them develop and retain deep process knowledge.

Lean wants companies to be small—neighborhood-small. When small companies build on a foundation of deep process knowledge, sales grow. Lean wants sales growth, but it also wants companies to reduce their size in the neighborhood sense.

Make It Where You Sell It

Lean has rolled through our factories and generated profits at every turn. Now it’s time to get serious about savings and realize the next level of savings. Companies are pushing lean into the back office, but that won’t get it done. The savings will be good, but not great. After picking low-hanging factory fruit, there’s uncertainty around what’s next for lean.

Lean has rolled through our factories and generated profits at every turn. Now it’s time to get serious about savings and realize the next level of savings. Companies are pushing lean into the back office, but that won’t get it done. The savings will be good, but not great. After picking low-hanging factory fruit, there’s uncertainty around what’s next for lean.

Make it where you sell it, that’s next for lean. Like a central theorem, this simple phrase will become lean’s mantra, and it will change everything, including our organizations themselves. The big multi-national companies have already started their journey, and we can take our cues from them.

The major automakers have assembly plants on all continents – objective evidence of make it where you sell it. There are many benefits to make it where you sell it, but the top three are: speed, speed, speed. The automotive value stream without make it where you sell it: make a car, put it on a boat, deliver it to a dealer, and sell it. Make it where you sell it eliminates the boat: make it, deliver it, and sell it. Inventory is proportional to cycle time and eliminating the long boat ride shortens the value stream, improves response time and reduces inventory.

Make it where you sell it starts closest to the customer, and final assembly is the first to be established in-market. Engines and transmissions still ride the boat, but not for long. After final assembly, make it where you sell it targets big, heavy, expensive subassemblies, so expect in-market engine and transmission plants. (However, big ones like these may stay put for while due to technological, political, or cultural reasons.)

With one piece flow, right-sized machines, and short product runs, lean has taught us the most economic scale is far smaller than we’d imagined. We’ve learned for our factories smaller is better, and make it where you sell it extrapolates smaller-is-better to the organization itself. Here again, the big guys lead the way. Multinationals are breaking themselves into smaller units, right-sizing into smaller regional companies – still big, but smaller. Their in-country manufacturing creates nice tight feedback loops between customer and factory. And there’s an important benefit to the brand – it becomes a local brand. Not only can the brand better serve regional tastes, it provides goodwill in the form of jobs.

[Disclaimer: I don’t advocate outsourcing. I’m simply explaining the forces at work and their consequences.]

Lean cares about speed, not countries, and make it where you sell it causes jobs flow across company boarders. This is especiallylevant as countries compete for manufacturing jobs like their survival depended on them. For those countries that understand manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of a sustainable economy, make it where you sell it can be threatening. If you’re a country that doesn’t buy a lot of manufactured goods, you and your economy trouble – jobs will flow to where products are sold.

Make it where you sell it won’t stop at making, and will extend up stream. The next logical extension is design it where you sell it, R&D it where you sell it, and innovate it where you sell it. (The biggest companies are already doing this with regional R&D centers.) More jobs will flow across borders, but this time they’ll be the coveted thinking jobs.

Make it where you sell it is the guiding principle companies are using to become more responsive, more productive, and local. It has already broken the biggest companies into smaller ones. They’ve realized that the most economic scale is small, and they’re getting there using make it where you sell it.

Make it where you sell it will change all companies, even small ones. And the mantra for small companies: think narrow and deep.

I will hold a half-day Workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment on June 13 in RI. (See bottom of linked page.) I look forward to meeting you in person.

Fix The Economy – Connect The Engineer To The Factory

Rumor has it, manufacturing is back. Yes, manufacturing jobs are coming back, but they’re coming back in dribbles. (They left in a geyser, so we still have much to do.) What we need is a fire hose of new manufacturing jobs.

Rumor has it, manufacturing is back. Yes, manufacturing jobs are coming back, but they’re coming back in dribbles. (They left in a geyser, so we still have much to do.) What we need is a fire hose of new manufacturing jobs.

Manufacturing jobs are trickling back from low cost countries because companies now realize the promised labor savings are not there and neither is product quality. But a trickle isn’t good enough; we need to turn the tide; we need the Mississippi river.

For flow like that we need a fundamental change. We need labor costs so low our focus becomes good quality; labor costs so low our focus becomes speed to market; labor costs so low our focus becomes speed to customer. But the secret is not labor rate. In fact, the secret isn’t even in the factory.

The secret is a secret because we’ve mistakenly mapped manufacturing solely to making (to factories). We’ve forgotten manufacturing is about designing and making. And that’s the secret: designing – adding product thinking to the mix. Design out the labor.

There are many names for designing and making done together. Most commonly it’s called concurrent engineering. Though seemingly innocuous, taken together, those words have over a thousand meanings layered with even more nuances. (Ask someone for a simple description of concurrent engineering. You’ll see.) It’s time to take a step back and demystify designing and making done together. We can do this with two simple questions:

- What behavior do we want?

- How do we get it?

What’s the behavior we want? We want design engineers to understand what drives cost in the factory (and suppliers’ factories) and design out cost. In short, we want to connect the engineer to the factory.

Great idea. But what if the factory and engineer are separated by geography? How do we get the behavior we want? We need to create a stand-in for the factory, a factory surrogate, and connect the engineer to the surrogate. And that surrogate is cost. (Cost is realized in the factory.) We get the desired behavior when we connect the engineer to cost.

When we make engineering responsible for cost (connect them to cost), they must figure out where the cost is so they can design it out. And when they figure out where the cost is, they’re effectively connected to the factory.

But the engineers don’t need to understand the whole factory (or supply chain), they only need to understand places that create cost (where the cost is.) To understand where cost is, they must look to the baseline product – the one you’re making today. To help them understand supply chain costs, ask for a Pareto chart of cost by part number for purchased parts. (The engineers will use cost to connect to suppliers’ factories.) The new design will focus on the big bars on the left of the Pareto – where the supply chain cost is.

To help them understand your factory’s cost, they must make two more Paretos. The first one is a Pareto of part count by major subassembly. Factory costs are high where the parts are – time to put them together. The second is a Pareto chart of process times. Factory costs are high where the time is – machine capacity, machine operators, and floor space.

To make it stick, use design reviews. At the first design review – where their design approach is defined – ask engineering for the three Paretos for the baseline product. Use the Pareto data to set a cost reduction goal of 50% (It will be easily achieved, but not easily believed.) and part count reduction goal of 50%. (Easily achieved.) Here’s a hint for the design review – their design approach should be strongly shaped by the Paretos.

Going forward, at every design review, ask engineering to present the three Paretos (for the new design) and cost and part count data (for the new design.) Engineering must present the data themselves; otherwise they’ll disconnect themselves from the factory.

To seal the deal, just before full production, engineering should present the go-to-production Paretos, cost, and part count data.

What I’ve described may not be concurrent engineering, but it’s the most profitable activity you’ll ever do. And, as a nice side benefit, you’ll help turn around the economy one company at a time.

Seeing Things As They Are

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

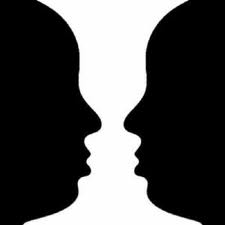

With the wicked couple of competition and profitability goals, we’re under a lot of pressure. And with the pressure comes the danger of seeing things how we want them instead of how they are, like a self-created optical illusion. Here are some likely optical illusion A-B pairs (A – how we want things; B – how they are):

A. Give people more work and more gets done. B. Human output has a physical limit, and once reached less gets done – and spouses get angry. A. Do more projects in parallel to generate more profit. B. Business processes have physical limits, and once reached projects slow and everyone works harder for the same output. A. Add resources to the core project team and more projects get done. B. Add resources to core projects teams and utilization skyrockets for shared resources – waiting time increases for all. A. Use lean in product development (just like in manufacturing) to launch new products better and faster. B. Lean done in product development is absolutely different than in manufacturing, and design engineers don’t take kindly to manufacturing folks telling them how to do their work. A. Through negotiation and price reduction, suppliers can deliver cost reductions year-on-year. B. The profit equation has a physical limit (no profit), and once reached there is no supplier. A. Use lean to reduce product cost by 5%. B. Use DFMA to reduce product cost by 50%.Competition is severe and the pressure is real. And so is the danger to see things as we want them to be. But there’s a simple way to see things as they are: ask the people that do the work. Go to the work and ask the experts. They do the work day-in-day-out, and they know what really happens. They know the details, the pinch points, and the critical interactions.

To see things as they are, check your ego at the door, and go ask the experts – the people that do the work.

Lean and Supply Chain Sensitivity

At every turn, lean has increased profits in the factory. Its best trick is to look at the work through a time lens, see wasted time, and get rid of it.

At every turn, lean has increased profits in the factory. Its best trick is to look at the work through a time lens, see wasted time, and get rid of it.

Work is blocked by problems. You watch the work to spot blockages in the form of piles, otherwise known as inventory. When you find a pile, you know the problem is one operation downstream.

As lean works its magic, inventory is reduced, which decreases carrying costs. More importantly, however, it also reduces the time to see a problem. Whether the problem is related to quality, delivery or resources, everything stops immediately. It’s clear what to fix, and there’s incentive to fix it quickly because with lean, the factory is more sensitive to problems.

What works in the factory will also work in the supply chain, and that’s where lean is going.

Radically Simplify Your Value Stream – Change Your Design

The next level of factory simplification won’t come from your factory. It will come from outside your factory. The next level of simplification will come from upstream savings – your suppliers’ factories – and downstream savings – your distribution system. And this next level of simplification will create radically shorter value streams (from raw materials to customer.)

The next level of factory simplification won’t come from your factory. It will come from outside your factory. The next level of simplification will come from upstream savings – your suppliers’ factories – and downstream savings – your distribution system. And this next level of simplification will create radically shorter value streams (from raw materials to customer.)

To reinvent your value stream, traditional lean techniques – reduction of non-value added (NVA) time through process change – aren’t the best way. The best way is to eliminate value added (VA) time through product redesign – product change. Reduction of VA time generates a massive NVA savings multiple. (Value streams are mostly NVA with a little VA sprinkled in.) At first this seems like backward thinking (It is bit since lean focuses exclusively on NVA.), but NVA time exists only to enable VA time (VA work). No VA time, no associated NVA time.

Value streams are all about parts (making them, counting them, measuring them, boxing them, moving them, and un-boxing them) and products (making, boxing, moving.) The making – touch time, spindle time – is VA time and everything else is VA time. Design out the parts themselves (VA time) and NVA time is designed out. Massive multiple achieved.

But the design community is the only group that can design out the parts. How to get them involved? Not all parts are created equal. How to choose the ones that matter? Value streams cut across departments and companies. How to get everyone pulling together?

Watch the video: link to video. (And embedded below.)

How To Create a Sea of Manufacturing Jobs

It’s been a long slide from greatness for US manufacturing. It’s been downhill since the 70s – a multi-decade slide. Lately there’s a lot of hype about a manufacturing renaissance in the US – re-shoring, on-shoring, right-shoring. But the celebration misguided. A real, sustainable return to greatness will take decades, decades of single-minded focus, coordination, alignment and hard work – industry, government, and academia in it together for the long haul.

It’s been a long slide from greatness for US manufacturing. It’s been downhill since the 70s – a multi-decade slide. Lately there’s a lot of hype about a manufacturing renaissance in the US – re-shoring, on-shoring, right-shoring. But the celebration misguided. A real, sustainable return to greatness will take decades, decades of single-minded focus, coordination, alignment and hard work – industry, government, and academia in it together for the long haul.

To return to greatness, the number of new manufacturing jobs to be created is distressing. 100,000 new manufacturing jobs is paltry. And today there is a severe skills gap. Today there are unfilled manufacturing jobs because there’s no one to do the work. No one has the skills. With so many without jobs it sad. No, it’s a shame. And the manufacturing talent pipeline is dry – priming before filling. Creating a sea of new manufacturing jobs will be hard, but filling them will be harder. What can we do?

The first thing to do is make list of all the open manufacturing jobs and categorize them. Sort them by themes: by discipline, skills, experience, tools. Use the themes to create training programs, train people, and fill the open jobs. (Demonstrate coordinated work of government, industry, and academia.) Then, using the learning, repeat. Define themes of open manufacturing jobs, create training programs, train, and fill the jobs. After doing this several times there will be sufficient knowledge to predict needed skills and proactive training can begin. This cycle should continue for decades.

Now the tough parts – transcending our short time horizon and finding the money. Our time horizon is limited to the presidential election cycle – four years, but the manufacturing rebirth will take decades. Our four year time horizon prevents success. There needs to be a guiding force that maintains consistency of purpose – manufacturing resurgence – a consistency of purpose for decades. And the resurgence cannot require additional money. (There isn’t any.) So who has a long time horizon and money?

The DoD has both – the long term view (the military is not elected or appointed) and the money. (They buy a lot of stuff.) Before you call me a war hawk, this is simply a marriage of convenience. I wish there was, but there is no better option.

The DoD should pull together their biggest contractors (industry) and decree that the stuff they buy will have radically reduced cost signatures and teach them and their sub-tier folks how to get it done. No cost reduction, no contract. (There’s no reason military stuff should cost what it does, other than the DoD contractors don’t know how design things cost effectively.) The DoD should educate their contractors how to design products to reduce material cost, assembly time, supply chain complexity, and time to market and demand the suppliers. Then, demand they demonstrate the learning by designing the next generation stuff. (We mistakenly limit manufacturing to making, when, in fact, radical improvement is realized when we see manufacturing as designing and making.)

The DoD should increase its applied research at the expense of its basic research. They should fund applied research that solves real problems that result in reduced cost signatures, reduce total cost of ownership, and improved performance. Likely, they should fund technologies to improve engineering tools, technologies that make themselves energy independent and new materials. Once used in production-grade systems, the new technologies will spill into non-DoD world (broad industry application) and create new generation products and a sea of manufacturing jobs.

I think this is approach has a balanced time horizon – fill manufacturing jobs now and do the long term work to create millions of manufacturing jobs in the future.

Yes, the DoD is at the center of the approach. Yes, some have a problem with that. Yes, it’s a marriage of convenience. Yes, it requires coordination among DoD, industry, and academia. Yes, that’s almost impossible to imagine. Yes, it requires consistency of purpose over decades. And, yes, it’s the best way I know.

What is Design for Manufacturing and Assembly?

Design for Manufacturing (DFM) is all about reducing the cost of piece-parts. Design for Assembly is all about reducing the cost of putting things together (assembly). What’s often forgotten is that function comes first. Change the design to reduce part cost, but make sure the product functions well. Change the parts (eliminate them) to reduce assembly cost, but make sure the product functions well.

Paradoxically, DFM and DFA are all about function.

Here’s a link to a short video that explains DFM and DFA: link to video. (and embedded below)

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski