Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

Systematic Innovation

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

To put one of these innovation systems in place, the first step is to define the group that will make the decisions. Let’s call them the Decision Group, or DG for short. (By the way, this is the same group that regularly orients itself with the information steams.) And the theme of the decisions is how to deploy the organization’s resources. The decision group (DG) should be diverse so it can see things from multiple perspectives.

The DG uses the company’s mission and growth objectives as their guiding principles to set growth goals for the innovation work, and those goals are clearly placed within the context of the company’s mission.

The first action is to orient the DG in the past. Resources are allocated to analyze the product launches over the past ten years and determine the lines of ideality (themes of goodness, from the customers’ perspective). These lines define the traditional ideality (traditional themes of goodness provided by your products) are then correlated with historical profitability by sales region to evaluate their importance. If new technology projects provide value along these traditional lines, the projects are continuous improvement projects and the objective is market share gain. If they provide extreme value along traditional lines, the projects are of the dis-continuous improvement flavor and their objective is to grow the market. If the technology projects provide value along different lines and will be sold to a different customer base, the projects could be disruptive and could create new markets.

The next step is to put in place externally focused information streams which are used for continuous observation and continual orientation. An example list includes: global and regional economic factors, mergers/acquisitions/partnerships, legal changes, regulatory changes, geopolitical issues, competitors’ stock price and quarterly updates, and their new products and patents. It’s important to format the output for easy visualization and to make collection automatic.

Then, internally focused information streams are put in place that capture results from the actions of the project team and deliver them, as inputs, for observation and orientation. Here’s an example list: experimental results (technology and market-centric), analytical results (technical and market), social media experiments, new concepts from ideation sessions (IBEs), invention disclosures, patent filings, acquisition results, product commercialization results and resulting profits. These information streams indicate the level of progress of the technology projects and are used with the external information streams to ground the DG’s orientation in the achievements of the projects.

All this infrastructure, process, and analysis is put in place to help the DG make good (and fast) decisions about how to allocate resources. To make good decisions, the group continually observes the information streams and continually orients themselves in the reality of the environment and status of the projects. At this high level, the group decides not how the project work is done, rather what projects are done. Because all projects share the same resource pool, new and existing projects are evaluated against each other. For ongoing work the DG’s choice is – stop, continue, or modify (more or less resources); and for new work it’s – start, wait, or never again talk about the project.

Once the resource decision is made and communicated to the project teams, the project teams (who have their own decision groups) are judged on how well the work is executed (defined by the observed results) and how quickly the work is done (defined by the time to deliver results to the observation center.)

This innovation system is different because it is a double learning loop. The first one is easy to see – results of the actions (e.g., experimental results) are fed back into the observation center so the DG can learn. The second loop is a bit more subtle and complex. Because the group continuously re-orients itself, it always observes information from a different perspective and always sees things differently. In that way, the same data, if observed at different times, would be analyzed and synthesized differently and the DG would make different decisions with the same data. That’s wild.

The pace of this double learning loop defines the pace of learning which governs the pace of innovation. When new information from the streams (internal and external) arrive automatically and without delay (and in a format that can be internalized quickly), the DG doesn’t have to request information and wait for it. When the DG makes the resource-project decisions it’s always oriented within the context of latest information, and they don’t have to wait to analyze and synthesize with each other. And when they’re all on the same page all the time, decisions don’t have to wait for consensus because it already has. And when the group has authority to allocate resources and chooses among well-defined projects with clear linkage to company profitability, decisions and actions happen quickly. All this leads to faster and better innovation.

There’s a hierarchical set of these double learning loops, and I’ve described only the one at the highest level. Each project is a double learning loop with its own group of deciders, information streams, observation centers, orientation work and actions. These lower level loops are guided by the mission of the company, goals of the innovation work, and the scope of their projects. And below project loops are lower-level loops that handle more specific work. The loops are fastest at the lowest levels and slowest at the highest, but they feed each other with information both up the hierarchy and down.

The beauty of this loop-based innovation system is its flexibility and adaptability. The external environment is always changing and so are the projects and the people running them. Innovation systems that employ tight command and control don’t work because they can’t keep up with the pace of change, both internally and externally. This system of double loops provides guidance for the teams and sufficient latitude and discretion so they can get the work done in the best way.

The most powerful element, however, is the almost “living” quality of the system. Over its life, through the work itself, the system learns and improves. There’s an organic, survival of the fittest feel to the system, an evolutionary pulse, that would make even Darwin proud.

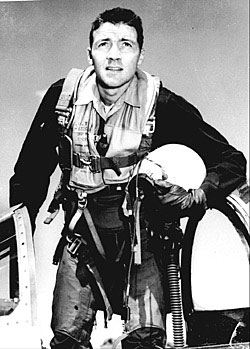

But, really, it’s Colonel John Boyd who should be proud because he invented all this. And he called it the OODA loop. Here’s his story – Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War.

Where possible, I have used Boyd’s words directly, and give him all the credit. Here is a list of his words: observe, orient, decide, act, analyze-synthesize, double loop, speed, organic, survival of the fittest, evolution.

Image attribution – U.S. Government [public domain]. by wikimedia commons.

The Lonely Chief Innovation Officer

Chief Innovation Officer is a glorious title, and seems like the best job imaginable. Just imagine – every-day-all-day it’s: think good thoughts, imagine the future, and bring new things to life. Sounds wonderful, but more than anything, it’s a lonely slog.

Chief Innovation Officer is a glorious title, and seems like the best job imaginable. Just imagine – every-day-all-day it’s: think good thoughts, imagine the future, and bring new things to life. Sounds wonderful, but more than anything, it’s a lonely slog.

In theory it’s a great idea – help the company realize (and acknowledge) what it’s doing wrong (and has been for a long time now), take resources from powerful business units and move them to a fledgling business units that don’t yet sell anything, and do it without creating conflict. Sounds fun, doesn’t it?

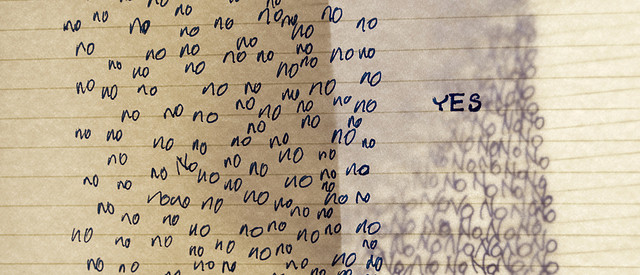

Though there are several common problems with the role of Chief Innovation Officer (CIO), the most significant structural issue, by far, is the CIO has no direct control over how resources are allocated. Innovation creates products, services and business models that are novel, useful and successful. That means innovation starts with ideas and ends with commercialized products and services. And no getting around it, this work requires resources. The CIO is charged with making innovation come to be, yet authority to allocate resources is withheld. If you’re thinking about hiring a Chief Innovation Officer, here’s a rule to live by:

If resources are not moved to projects that generate novel ideas, convert those ideas into crazy prototypes and then into magical products that sell like hotcakes, even the best Chief Innovation Officer will be fired within two years.

Structurally, I think it’s best if the powerful business units (who control the resources) are charged with innovation and the CIO is charged with helping them. The CIO helps the business units create a forward-looking mindset, helps bring new thinking into the old equation, and provides subject matter expertise from outside the company. While this addresses the main structural issue, it does not address the loneliness.

The CIO’s view of what worked is diametrically opposed to those that made it happen. Where the business units want to do more of what worked, the CIO wants to dismantle the engine of success. Where the engineers that designed the last product want to do wring out more goodness out of the aging hulk that is your best product, the CIO wants to obsolete it. Where the business units see the tried-and-true business model as the recipe for success, the CIO sees it as a tired old cowpath leading to the same old dried up watering hole. If this sounds lonely, it’s because it is.

To combat this fundamental loneliness, the CIO needs to become part of a small group of trusted CIOs from non-competing companies. (NDAs required, of course.) The group provides its members much needed perspective, understanding and support. At the first meeting the CIO is comforted by the fact that loneliness is just part of the equation and, going forward, no longer takes it personally. Here are some example deliverables for the group.

Identify the person who can allocate resources and put together a plan to help that person have a big problem (no incentive compensation?) if results from the innovation work are not realized.

Make a list of the active, staffed technology projects and categorize them as: improving what already exists, no-to-yes (make a product/service do something it cannot), or yes-to-no (eliminate functionality to radically reduce the cost signature and create new markets).

For the active, staffed projects, define the market-customer-partner assumptions (market segment, sales volume, price, cost, distribution and sales models) and create a plan to validate (or invalidate) them.

To the person with the resources and the problem if the innovation work fizzles, present the portfolio of the active, staffed projects and its validated roll-up of net profit, and ask if portfolio meets the growth objectives for the company. If yes, help the business execute the projects and launch the products/services. If no, put a plan together to run Innovation Burst Events (IBEs) to come up with more creative ideas that will close the gap.

The burning question is – How to go about creating a CIO group from scratch? For that, you need to find the right impresario that can pull together a seemingly disparate group of highly talented CIOs, help them forge a trusting relationship and bring them the new thinking they need.

Finding someone like that may be the toughest thing of all.

Image credit – Giant Humanitarian Robot.

The Best Leading Indicator of Innovation

Evaluation of innovation efforts is a hot topic. Sometimes it seems evaluating innovation is more important than innovation itself.

Evaluation of innovation efforts is a hot topic. Sometimes it seems evaluating innovation is more important than innovation itself.

Metrics, indicators, best practices, success stories – everyone is looking for the magical baseline data to compare to in order to define shortcomings and close them. But it’s largely a waste of time, because with innovation, it’s different every time. Look back two years – today’s technology is different, the market is different, and the people are different. If you look back and evaluate what went on and then use that learning to extrapolate what will happen in the future, well, that’s like driving a Formula One car around the track while looking in the rear view mirror. You will crash and you will get hurt because, by definition, with innovation, what you did in the past no longer applies, even to you.

Here’s a rule – when you look backward to steer your innovation work, you crash.

When you compare yourself to someone else’s innovation rearward looking innovation metrics, it’s worse. Their market was different than yours is, their company culture was different than yours is, their company mission and values were different. Their situation no longer applies to them and it’s less applicable to you, yet that’s what you’re doing when you compare yourself to a rearview mirror look at a best practice company. Crazy.

We’re fascinated with innovation metrics that are easy to measure, but we shouldn’t be. Anything that’s easy to measure cannot capture the nuance of innovation. For example, the number of innovation projects you ran over the last two years is meaningless. What’s meaningful is the incremental profit generated by the novel deliverables of the work and your level of happiness with the incremental profit. Number of issued patents is also meaningless. What’s meaningful is the incremental profit created by the novel goodness of the patented technology and your level of happiness with it. Number of people that worked on innovation projects or the money spent – meaningless. Meaningful – incremental profit generated by the novel elements of the work divided by the people (or cost) that created the novel elements and your level of happiness with it.

Things are a bit better with forward looking metrics – or leading indicators – but not much. Again, our fascination with things that are easy to measure kicks us in the shins. Number of patent applications, number of people working on projects, number of fully staffed technology projects, monthly spend on R&D – all of these are easily measured but are poor predictors innovation results. What if the patented technology is not valued by the customer? What if the people working on projects are working on projects that result in products that don’t sell? What if the fully staffed projects create new technologies for new markets that never come to be? What if your monthly spend is spent on projects that miss the mark?

To me, the only meaningful leading indicator for innovation is a deep understanding of your active technology projects. What must the technology do so the new market will buy it? How do you know that? Can you quantify that goodness in a quantifiable way? Will you know when that goodness has been achieved? In what region will the product be sold? What is the cost target, profit margin and the new customers’ ability to pay? What are the results of the small experiments where the team tested the non-functional prototypes and their price points in the new market? What does the curve look like for price point versus sales volume? What is your level of happiness with all this?

We have an unhealthy fascination with innovation metrics that are easy to measure. Instead of a sea of metrics that are easy to measure, we need nuanced leading indicators that are meaningful. And I cannot give you a list of meaningful leading indicators, because each company has a unique list which is defined by its growth objectives, company culture and values, business models, and competition. And I cannot give you threshold limits for any of them because only you can define that. The leading indicators and their threshold values are context-specific – only you can choose them and only you can judge what levels make you happy. Innovation is difficult because it demands judgment, and no metrics or leading indicators can take judgment out of the equation.

Creativity creates things that are novel and useful while innovation creates things that are novel, useful and successful. Dig into the details of your active technology projects and understand them from a customer-market perspective, because success comes only when customers buy your new products.

Image credit – coloneljohnbritt

Constructive Conflict

Innovation starts with different, and when you propose something that’s different from the recipe responsible for success, innovation becomes the enemy of success. And because innovation and different are always joined at the hip, the conflict between success and innovation is always part of the equation. Nothing good can come from pretending the conflict does not exist, and it’s impossible to circumvent. The only way to deal with the conflict is to push through it.

Innovation starts with different, and when you propose something that’s different from the recipe responsible for success, innovation becomes the enemy of success. And because innovation and different are always joined at the hip, the conflict between success and innovation is always part of the equation. Nothing good can come from pretending the conflict does not exist, and it’s impossible to circumvent. The only way to deal with the conflict is to push through it.

Emotional energy is the forcing function that pushes through conflict, and the only people that can generate it are the people doing the work. As a leader, your job is to create and harness this invisible power, and for that, you need mechanisms.

To start, you must map innovation to “different”. The first trick is to ask for ideas that are different. Where brainstorming asks for quantity, firmly and formally discredit it and ask for ideas that are different. And the more different, the better. Jeffrey Baumgartner has it right with his Anticonventional Thinking (ACT) methodology where he pushes even further and asks for ideas that are anti-conventional.

The intent is to create emotional energy, and to do that there’s nothing better than telling the innovation team their ideas are far too conventional. When you dismiss their best ideas because they’re not different enough, you provide clear contrast between the ideas they created and the ones you want. And this contrast creates internal conflict between their best thinking and the thinking you want. This internal conflict generates the magical emotional energy needed to push through the conflict between innovation and success. In that way, you create intrinsic conflict to overpower the extrinsic conflict.

Because innovation is powered by emotional energy, conflict is the right word. Yes, it feels too strong and connotes quarrel and combat, but it’s the right word because it captures the much needed energy and intensity around the work. Just as when “opportunity” is used in place of “problem” and the urgency, importance, and emotion of the situation wanes, emotional energy is squandered when other words are used in place of “conflict”.

And it’s also the right word when it comes to solutions. Anti-conventional ideas demand anti-conventional solutions, both of which are powered by emotional energy. In the case of solutions, though, the emotional energy around “conflict” is used to overcome intellectual inertia.

Solving problems won’t get you mind-bending solutions, but breaking conflicts will. The idea is to use mechanisms and language to move from solving problems to breaking conflicts. Solving problems is regular work done as a matter of course and regular work creates regular solutions. But with innovation, regular solutions won’t cut it. We need irregular solutions that break from the worn tracks of predictable thinking. And do to this, all convention must be stripped away and all attachments broken to see and think differently. And, to jolt people out of their comfort zone, contrast must be clearly defined and purposefully amplified.

The best method I know to break intellectual inertia is ARIZ and algorithmic method for innovative solutions built on the foundation of TRIZ. With ARIZ, a functional model of the system is created using verb-noun pairs with the constraint that no industry jargon can be used. (Jargon links the mind to traditional thinking.) Then, for clarity, the functional model is then reduced to a conflict between two system elements and defined in time and place (the conflict domain.) The conflict is then made generic to create further distance from the familiar. From there the conflict is purposefully amplified to create a situation where one of the conflicting elements must be in two states at the same time (conflicting states) – hot and cold; large and small; stiff and flexible. The conflicting states make it impossible to rely on preexisting solutions (familiar thinking.) Though this short description of ARIZ doesn’t do it justice, it does make clear ARIZ’s intention – to use conflicts to break intellectual inertia.

Innovation butts heads and creates conflict with almost everything, but it’s not destructive conflict. Innovation has the best intentions and wants only to create constructive conflict that leads to continued success. Innovation knows your tired business model is almost out of gas and desperately wants to create its replacement, but it knows your successful business model and its tried-and-true thinking are deeply rooted in the organization. And innovation knows the roots are grounded in emotion and it’s not about pruning it’s about emotional uprooting.

Conflict is a powerful word, but the right word. Use the ACT mechanism to ask for ideas that constructively conflict with your success and use the ARIZ mechanism to ask for solutions that constructively conflict with your best thinking.

With innovation there is always conflict. You might as well make it constructive conflict and pull your organization into the future kicking and screaming.

Image credit – Kevin Thai

Innovation Fortune Cookies

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If you know how it will turn out, you waited too long.

Whether you like it or not, when you start something new uncertainty carries the day.

Don’t define the idealized future state, advance the current state along its lines of evolutionary potential.

Try new things then do more of what worked and less of what didn’t.

Without starting, you never start. Starting is the most important part

Perfection is the enemy of progress, so are experts.

Disruption is the domain of the ignorant and the scared.

Innovation is 90% people and the other half technology.

The best training solves a tough problem with new tools and processes, and the training comes along for the ride.

The only thing slower than going too slowly is going too quickly.

An innovation best practice – have no best practices.

Decisions are always made with judgment, even the good ones.

image credit – Gwen Harlow

Battle Success With No-To-Yes

Everyone says they want innovation, but they don’t – they want the results of innovation.

Everyone says they want innovation, but they don’t – they want the results of innovation.

Innovation is about bringing to life things that are novel, useful and successful. Novel and useful are nice, but successful pays the bills. Novel means new, and new means fear; useful means customers must find value in the newness we create, and that’s scary. No one likes fear, and, if possible, we’d skip novel and useful altogether, but we cannot. Success isn’t a thing in itself, success is a result of something, and that something is novelty and usefulness.

Companies want success and they want it with as little work and risk as possible, and they do that with a focus on efficiency – do more with less and stock price increases. With efficiency it’s all about getting more out of what you have – don’t buy new machines or tools, get more out of what you have. And to reduce risk it’s all about reducing newness – do more of what you did, and do it more efficiently. We’ve unnaturally mapped success with the same old tricks done in the same old way to do more of the same. And that’s a problem because, eventually, sameness runs out of gas.

Innovation starts with different, but past tense success locks us into future tense sameness. And that’s the rub with success – success breeds sameness and sameness blocks innovation. It’s a strange duality – success is the carrot for innovation and also its deterrent. To manage this strange duality, don’t limit success; limit how much it limits you.

The key to busting out of the shackles of your success is doing more things that are different, and the best way to do that is with no-to-yes.

If your product can’t do something then you change it so it can, that’s no-to-yes. By definition, no-to-yes creates novelty, creates new design space and provides the means to enter (or create) new markets. Here’s how to do it.

Scan all the products in your industry and identify the product that can operate with the smallest inputs. (For example, the cell phone that can run on the smallest battery.) Below this input level there are no products that can function – you’ve identified green field design space which you can have all to yourself. Now, use the industry-low input to create a design constraint. To do this, divide the input by two – this is the no-to-yes threshold. Before you do you the work, your product cannot operate with this small input (no), but after your hard work, it can (yes). By definition the new product will be novel.

Do the same thing for outputs. Scan all the products in your industry to find the smallest output. (For example, the automobile with the smallest engine.) Divide the output by two and this is your no-to-yes threshold. Before you design the new car it does not have an engine smaller than the threshold (no), and after the hard work, it does (yes). By definition, the new car will be novel.

A strange thing happens when inputs and outputs are reduced – it becomes clear existing technologies don’t cut it, and new, smaller, lower cost technologies become viable. The no-to-yes threshold (the constraint) breaks the shackles of success and guides thinking in a new directions.

Once the prototypes are built, the work shifts to finding a market the novel concept can satisfy. The good news is you’re armed with prototypes that do things nothing else can do, and the bad news is your existing customers won’t like the prototypes so you’ll have to seek out new customers. (And, really, that’s not so bad because those new customers are the early adopters of the new market you just created.)

No-to-yes thinking is powerful, and though I described how it’s used with products, it’s equally powerful for services, business models and systems.

If you want innovation (and its results), use no-to-yes thinking to find the limits and work outside them.

Innovation Through Preparation

Innovation is about new; innovation is about different; innovation is about “never been done before”; and innovation is about preparation.

Innovation is about new; innovation is about different; innovation is about “never been done before”; and innovation is about preparation.

Though preparation seems to contradict the free-thinking nature of innovation, it doesn’t. In fact, where brainstorming diverts attention, the right innovation preparation focuses it; where brainstorming seeks more ideas, preparation seeks fewer and more creative ones; where brainstorming does not constrain, effective innovation preparation does exactly that.

Ideas are the sexy part of innovation; commercialization is the profitable part; and preparation is the most important part. Before developing creative, novel ideas, there must be a customer of those ideas, someone that, once created, will run with them. The tell-tale sign of the true customer is they have a problem if the innovation (commercialization) doesn’t happen. Usually, their problem is they won’t make their growth goals or won’t get their bonus without the innovation work. From a preparation standpoint, the first step is to define the customer of the yet-to-be created disruptive concepts.

The most effective way I know to create novel concepts is the IBE (Innovation Burst Event), where a small team gets together for a day to solve some focused design challenges and create novel design concepts. But before that can happen, the innovation preparation work must happen. This work is done in the Focus phase. The questions and discussion below defines the preparation work for a successful IBE.

1. Why is it so important to do this innovation work?

What defines the need for the innovation work? The answer tells the IBE team why they’re in the room and why their work is important. Usually, the “why” is a growth goal at the business unit level or projects in the strategic plan that are missing the necessary sizzle. If you can’t come up with a slide or two with growth goals or new projects, the need for innovation is only emotional. If you have the slides, these will be used to kick off the IBE.

2. Who is the customer of the novel concepts?

Who will choose which concepts will be converted into working prototypes? Who will convert the prototypes into new products? Who will launch the new products? Who has the authority to allocate the necessary resources? These questions define the customers of the new concepts. Once defined, the customers become part of the IBE team. The customers kick off the IBE and explain why the innovation work is important and what they’ll do with the concepts once created. The customers must attend the IBE report-out and decide which concepts they’ll convert to working prototypes and patents.

Now, so the IBE will generate the right concepts, the more detailed preparation work can begin. This work is led by marketing. Here are the questions to scope and guide the IBE.

3. How will the innovative new product be used?

How will the innovative product be used in new way? This question is best answered with a hand sketch of the customer using the new product in a new way, but a short written description (30 words, or so) will do in a pinch. The answer gives the IBE team a good understanding, from a customer perspective, what new things the product must do.

What are the new elements of the design that enable the new functionality or performance? The answer focuses the IBE on the new design elements needed to make real the new product function in the new way.

What are the valuable customer outcomes (VCOs) enabled by the innovative new product? The answer grounds the IBE team in the fundamental reason why the customer will buy the new product. Again, this is answered from the customer perspective.

4. How will the new innovative new product be marketed and sold?

What is the tag line for the new product? The answer defines, at the highest level, what the new product is all about. This shapes the mindset of the IBE team and points them in the right direction.

What is the major benefit of the new product? The answer to this question defines what your marketing says in their marketing/sales literature. When the IBE team knows this, you can be sure the new concepts support the marketing language.

5. By whom will the innovative new product be used?

In which geography does the end user live? There’s a big difference between developed markets and developing markets. The answer to the question sets the context for the new concepts, specifically around infrastructure constraints.

What is their ability to pay? Pocketbooks are different across the globe, and the customer’s ability to pay guides the IBE team toward concepts that fit the right pocket book.

What is the literacy level of the end customer? If the customer can read, the IBE team creates concepts that take advantage of that ability. If the customer cannot read, the IBE team creates concepts that are far different.

6. How will the innovative new product change the competitive landscape?

Who will be angry when the new product hits the market? The answer defines the competition. It gives broad context for the IBE team and builds emotional energy around displacing adversaries.

Why will they be angry? With the answer to this one, the IBE team has good perspective on the flavor of pain and displeasure created by the concepts. Again, it shapes the perspective of the IBE team. And, it educates the marketing/sales work needed to address competitors’ countermeasures.

Who will benefit when the new product hits the market? This defines new partners and supporters that can be part of the new solutions or participants in a new business model or sales process.

What will customer throw away, reuse, or recycle? This question defines the level of disruption. If the new products cause your existing customers to throw away the products of your existing customers, it’s a pure market share play. The level of disruption is low and the level of disruption of the concepts should also be low. On the other end of the spectrum, if the new products are sold to new customers who won’t throw anything away, you creating a whole new market, which is the ultimate disruption, and the concepts must be highly disruptive. Either way, the IBE team’s perspective is aligned with the level appropriate level of disruption, and so are the new concepts.

Answering all these questions before the creative works seems like a lot of front-loaded preparation work, and it is. But, it’s also the most important thing you can do to make sure the concept work, technology work, patent work, and commercialization work gives your customers what they need and delivers on your company’s growth objectives.

Image credit — ccdoh1.

To improve innovation, improve clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

For clarity on the innovative new product, here’s what the CEO needs.

Valuable Customer Outcomes – how the new product will be used. This is done with a one page, hand sketched document that shows the user using the new product in the new way. The tool of choice is a fat black permanent marker on an 81/2 x 11 sheet of paper in landscape orientation. The fat marker prohibits all but essential details and promotes clarity. The new features/functions/finish are sketched with a fat red marker. If it’s red, it’s new; and if you can’t sketch it, you don’t have it. That’s clarity.

The new value proposition – how the product will be sold. The marketing leader creates a one page sales sheet. If it can’t be sold with one page, there’s nothing worth selling. And if it can’t be drawn, there’s nothing there.

Customer classification – who will buy and use the new product. Using a two column table on a single page, these are their attributes to define: Where the customer calls home; their ability to pay; minimum performance threshold; infrastructure gaps; literacy/capability; sustainability concerns; regulatory concerns; culture/tastes.

Market classification – how will it fit in the market. Using a four column table on a single page, define: At Whose Expense (AWE) your success will come; why they’ll be angry; what the customer will throw way, recycle or replace; market classification – market share, grow the market, disrupt a market, create a new market.

For clarity on the creative work, here’s what the CEO needs: For each novel concept generated by the Innovation Burst Event (IBE), a single PowerPoint slide with a picture of its thinking prototype and a word description (limited to 12 words).

For clarity on the problems to be solved the CEO needs a one page, image-based definition of the problem, where the problem is shown to occur between only two elements, where the problem’s spacial location is defined, along with when the problem occurs.

For clarity on the viability of the new technology, the CEO needs to see performance data for the functional prototypes, with each performance parameter expressed as a bar graph on a single page along with a hyperlink to the robustness surrogate (test rig), test protocol, and images of the tested hardware.

For clarity on commercialization, the CEO should see the project in three phases – a front, a middle, and end. The front is defined by a one page project timeline, one page sales sheet, and one page sales goals. The middle is defined by performance data (bar graphs) for the alpha units which are hyperlinked to test protocols and tested hardware. For the end it’s the same as the middle, except for beta units, and includes process capability data and capacity readiness.

It’s not easy to put things on one page, but when it’s done well clarity skyrockets. And with improved clarity the right concepts are created, the right problems are solved, the right data is generated, and the right new product is launched.

And when clarity extends all the way to the CEO, resources are aligned, organizational confusion dissipates, and all elements of innovation work happen more smoothly.

Image credit – Kristina Alexanderson

How It Goes With Innovation

Innovation starts with recognition of a big, meaningful problem. It can come from the strategic planning process; from an ongoing technology project that isn’t going well; an ongoing product development project that’s stuck in the trenches; or a competitor’s unforeseen action. But where it comes from isn’t the point. What matters is it’s recognized by someone important enough to allocate resources to make the problem go away. (If it’s recognized by someone who can’t muster the resources, it creates frustration, not progress.)

Innovation starts with recognition of a big, meaningful problem. It can come from the strategic planning process; from an ongoing technology project that isn’t going well; an ongoing product development project that’s stuck in the trenches; or a competitor’s unforeseen action. But where it comes from isn’t the point. What matters is it’s recognized by someone important enough to allocate resources to make the problem go away. (If it’s recognized by someone who can’t muster the resources, it creates frustration, not progress.)

Once recognized, the importance of the problem is communicated to the organization. Usually, a problem is important because it blocks growth, e.g., a missing element of the new business model, technology that falls short of the distinctive value proposition (DVP), or products that can’t deliver on your promises. But whether something’s in the way or missing, the problem’s importance is best linked to a growth objective.

Company leaders then communicate to the organization, using one page. Here’s an example:

WHY – we have a problem. The company’s stock price cannot grow without meeting the growth goals, and currently we cannot meet them. Here’s what’s needed.

WHAT – grow sales by 30%.

WHERE – in emerging markets.

WHEN – in two years.

HOW – develop a new line of products for the developing world.

Along with recognition of importance, there must be recognition that old ways won’t cut it and new thinking is required. That way the company knows it’s okay to try new things.

Company leaders pull together a small group and charters them to spend a bit of time to develop concepts for the new product line and come back and report their go-forward reccommendations. But before any of the work is done, resources are set aside to work on the best ones, otherwise no one will work on them and everyone will know the company is not serious about innovation.

To create new concepts, the small group plans an Innovation Burst Event (IBE). On one page they define the DVP for the new product line, which describes how the new customers will use the new products in new ways. They use the one page DVP to select the right team for the IBE and to define fertile design space to investigate. To force new thinking, the planning group creates creative constraints and design challenges to guide divergence toward new design space.

The off-site location is selected; the good food is ordered; the IBE is scheduled; and the team is invited. The company leader who recognized the problem kicks off the IBE with a short description of the problem and its importance, and tells the team she can’t wait to hear their recoomendations at the report-out at the end of the day.

With too little time, the IBE team steps through the design challenges, creates new concepts, and builds thinking prototypes. The prototypes are the center of attention at the report-out.

At the report-out, company leaders allocate IP resources to file patents on the best concepts and commission a team of marketers, technologists, and IP staff to learn if viable technologies are possible, if they’re patentable, and if the DVP is viable.(Will it work, can we patent it, and will they buy it.)

The marketer-technologist-IP team builds prototypes and tests them in the market. The prototypes are barely functional, if at all, and their job is to learn if the DVP resonates. (Think minimum viable prototype.) It’s all about build-test-learn, and the learning loops are fast and furious at the expese of statistical significance. (Judgement carries the day in this phase.)

With viable technology, patentable ideas, and DVP in hand, the tri-lobed team reports out to company leaders who sanctioned their work. And, like with the IBE, the leaders allocate more IP resources to file more patents and commission the commercialization team.

The commercialization team is the tried-and-true group that launches products. Design engineering makes it reliable; manufacturing makes it repeatable; marketing makes it irresistible; sales makes it successful. At the design reviews more patents are filed and at manufacturing readiness reviews it’s all about process capability and throughput.

Because the work is driven by problems that limit growth, the result of the innovation work is exactly what’s needed to fuel growth – in this case a successful product line for the developing world. Start with the right problem and end up with the right solution. (Always a good idea.)

With innovation programs, all the talk is about tools and methods, but the two things that really make the difference are lightning fast learning loops and resources to do the innovation work. And there’s an important philosophical chasm to cross – because patents are usually left out of the innovation equation – like an afterthought chasing a quota – innovation should become the umbrella over patents and technology. But because IP reports into finance and technology into engineering, it will be a tough chasm to bridge.

It’s clear fast learning loops are important for fast learning, but they’re also important for building culture. At the end of a cycle, the teams report back to leadership, and each report-out is an opportunity to shape the innovation culture. Praise the good stuff and ignore the rest, and the innovation culture moves toward the praise.

There’s a natural progression of the work. Start – do one project; spread – use the learning to do the next ones; systematize – embed the new behaviors into existing business processes; sustain – praise the best performers and promote them.

When innovation starts with business objectives, the objectives are met; when innovation starts with company leadership, resources are allocated and the work gets done; and when the work shapes the culture, the work accelerates. Anything less isn’t innovation.

Image credit – Jaybird

Don’t boost innovation, burst it.

The most difficult part of innovation is starting, and the best way to start is the Innovation Burst Event, or IBE. The IBE is a short, focused event with three objectives: to learn innovation methods, to provide hands-on experience, and to generate actual results. In short, the IBE is a great way to get started.

The most difficult part of innovation is starting, and the best way to start is the Innovation Burst Event, or IBE. The IBE is a short, focused event with three objectives: to learn innovation methods, to provide hands-on experience, and to generate actual results. In short, the IBE is a great way to get started.

There are a couple flavors of IBEs, but the most common is a single day even where a small, diverse group gets together to investigate some bounded design space and to create novel concepts. At the start, a respected company leader explains to the working group the importance of the day’s work, how it fits with company objectives, and sets expectations there will be a report out at the end of the day to review the results. During the event, the working group is given several design challenges, and using innovation tools/methods, creates new concepts and builds “thinking prototypes.” The IBE ends with a report out to company leaders, where the working group identifies patentable concepts and concepts worthy of follow-on work. Company leaders listen to the group’s recommendations and shape the go-forward actions.

The key to success is preparation. To prepare, interesting design space is identified using multiple inputs: company growth objectives, new market development, the state of the technology, competitive landscape and important projects that could benefit from new technology. And once the design space is identified, the right working group is selected. It’s best to keep the group small yet diverse, with several important business functions represented. In order to change the thinking, the IBE is held at location different than where the day-to-day work is done – at an off-site location. And good food is provided to help the working group feel the IBE is a bit special.

The most difficult and most important part of preparation is choosing the right design space. Since the selection process starts with your business objectives, the design space will be in line with company priorities, but it requires dialing in. The first step is to define the operational mechanism for the growth objective. Do you want a new product or process? A new market or business model? The next step is to choose if you want to radically improve what you have (discontinuous improvement) or obsolete your best work (disruption). Next, the current state is defined (knowing the starting point is more important than the destination) – Is the technology mature? What is the completion up to? What is the economy like in the region of interest? Then, with all that information, several important lines of evolution are chosen. From there, design challenges are created to exercise the design space. Now it’s time for the IBE.

The foundation of the IBE is the build-to-think approach and its building blocks are the design challenges. The working group is given a short presentation on an innovation tool, and then they immediately use the tool on a design challenge. The group is given a short description of the design challenge (which is specifically constructed to force the group from familiar thinking), and the group is given an unreasonably short time, maybe 15-20 minutes, to create solutions and build thinking prototypes. (The severe time limit is one of the methods to generate bursts of creativity.) The thinking prototype can be a story board, or a crude representation constructed with materials on hand – e.g., masking tape, paper, cardboard. The group then describes the idea behind the prototype and the problem it solves. A mobile phone is used to capture the thinking and the video is used at the report out session. The process is repeated one or two times, based on time constraints and nature of the design challenges.

About an hour before the report out, the working group organizes and rationalizes the new concepts and ranks them against impact and effort. They then recommend one or two concepts worthy of follow on work and pull together high level thoughts on next steps. And, they choose one or two concept that may be patentable. The selected concepts, the group’s recommendations, and their high level plans are presented at the report out.

At the report out, company leaders listen to the working group’s thoughts and give feedback. Their response to the group’s work is crucial. With right speech, the report out is an effective mechanism for leaders to create a healthy innovation culture. When new behaviors and new thinking are praised, the culture of innovation moves toward the praise. In that way, the desired culture can be built IBE by IBE and new behaviors become everyday behaviors.

Innovation is a lot more than Innovation Burst Events, but they’re certainly a central element. After the report out, the IBE’s output (novel concepts) must be funneled into follow on projects which must be planned, staffed, and executed. And then, as the new concepts converge on commercialization, and the intellectual comes on line, the focus of the work migrates to the factory and the sales force.

The IBE is designed to break through the three most common innovation blockers – no time to do innovation; lack of knowledge of how do innovation (though that one’s often unsaid); and pie-in-the-sky, brainstorming innovation is a waste of time. To address the time issue, the IBE is short – just one day. To address the knowledge gap, the training is part of the event. And to address the pie-in-the-sky – at the end of the day there is tangible output, and that output is directly in line with the company’s growth objectives.

It’s emotionally challenging to do work that destroys your business model and obsoletes your best products, but that’s how it is with innovation. But for motivation, think about this – if your business model is going away, it’s best if you make it go away, rather than your competition. But your competition does end up changing the game and taking your business, I know how they’ll do it – with Innovation Burst Events.

Image credit – Pascal Bovet

Starting starts with starting.

If you haven’t done it before and you want to start, you have only one option – to start.

If you haven’t done it before and you want to start, you have only one option – to start.

Much as there’s a huge difference between lightning and lightning bug, there’s a world of difference between starting and talking about starting. Where talking about starting flutters aimlessly flower to flower, starting jolts trees from the ground; fries all the appliances in your house; and leaves a smoldering crater in its wake. And where it’s easy to pick a lightning bug out of the grass and hold it in your hand, it’s far more difficult to grab lightning and wrestle it into submission.

Words to live by: When in mid conversation you realize you’re talking about starting – Stop talking and start starting. Some examples:

Instead of talking about starting a community of peers, send a meeting request to people you respect. Keep the group small for now, but set the agenda, hold the meeting, and set up the next one. You’re off and running. You started.

Replace your talk of growing a culture of trust with actions to demonstrate trust. Take active responsibility for the group’s new work that did not go as planned (aka – failure) so they feel safe to do more new work. Words don’t grow trust, only actions do.

Displace your words of building a culture of innovation with deeds that demonstrate caring. When someone does a nice job or goes out of their way to help, send words of praise in an email their boss – and copy them, of course. Down the road, when you want help with innovation you’ll get it because you cared enough to recognize good work. Ten emails equal twenty benefactors for your future innovation effort. Swap your talk of creating alignment with a meeting to thank the group for their special effort. But keep the meeting to two agenda items – 1. Thank you. 2. Pizza.

When it comes to starting, start small. When you can’t start because you don’t have permission, reduce size/scope until you do, and start. When you’re afraid to start, create a safe-to-fail experiment, and start. When no one asks you to start, that’s the most important time – build the minimum viable prototype you always wanted to build. Don’t ask – build. And if you’re afraid to start even the smallest thing because you think you may get fired – start anyway. Any company that fires you for taking initiative will be out of business soon enough. You might as well start.

Talk is cheap and actions are priceless. And if you never start a two year project you’re always two years away. Start starting.

Image credit – Vail Marston

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski