Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

Diabolically Simple Questions

Today’s work is complicated with electronic and mechanical subsystems wrapped in cocoons of software; coordination of matrixed teams; shared resources serving multiple projects; providing world class services in seventeen languages on four continents. And the complexity isn’t limited to high level elements. There is a living layer of complexity growing on all branches of the organization right down to the leaf level.

Today’s work is complicated with electronic and mechanical subsystems wrapped in cocoons of software; coordination of matrixed teams; shared resources serving multiple projects; providing world class services in seventeen languages on four continents. And the complexity isn’t limited to high level elements. There is a living layer of complexity growing on all branches of the organization right down to the leaf level.

Complexity is real, and it complicates things. To run projects and survive in the jungle of complexity it’s important to know how to put the right pieces together and provide the right answers. But as a leader it’s more important to slash through the complexity and see things as they are. And for that, it’s more important to know how ask diabolically simple questions (DSQ).

Project timelines are tight and project teams like to start as soon as they can. Too often teams start without clarity on what they’re trying to achieve. At these early stages the teams make record progress in the wrong direction. The leader’s job is to point them in the right direction, and here’s the DSQ to set them on their way: What are you trying to achieve?

There will likely be some consternation, arm waiving and hand wringing. After the dust settles, help the team further tighten down the project with this follow-on DSQ: How will you know you achieved it?

For previous two questions there are variants that works equally well for work that closer to the fuzzy front end: What are you trying to learn? and How will you know you learned it?

There is no such thing as a clean-sheet project and even the most revolutionary work builds on the existing system. Though the existing business model, service or product has been around for a long time, the project team doesn’t really know how it works. They know they should know but they’re afraid to admit it. Let them off the hook with this beauty: How does it work today?

After the existing system is defined with a simple block diagram (which could take a couple weeks) it’s time to help the project team focus their work. The best DSQ for the job: How is it different from the existing system? If the list is too long there’s too much newness and if it’s too short there’s not enough novelty. If they don’t know what’s different, ask them to come back when they know.

After the “what’s different” line of questioning, the team must be able to dive deeper. For that it’s time one of the most powerful DSQs in the known universe: What problem are you trying to solve? Expect frustration and complicated answers. Ask them to take some time and for each problem describe it on a single page using less than ten words. Suggest a block diagram format and ask them to define where and when the problem occurs. (Hint: a problem is always between two components/elements of the system.) And the tricky follow-on DSQ: How will you know you solved it? No need to describe the reaction to that one.

Though not an exhaustive list, here are some of my other favorite DSQs:

Who will buy it, how much will they pay, and how do you know?

Have we done this before?

Have you shown it to a real customer?

How much will it cost and how do you know?

Whose help do we need?

If the prototype works, will we actually do anything with it?

Diabolically simple questions have the power to heal the project teams and get them back on track. And over time, DSQs help the project teams adopt a healthy lifestyle. In that way, DSQs are like medicine – they taste bad but soon enough you feel better.

Image credit – Daniela Hartmann

How To Allocate Resources

How a company allocates its resources defines its strategy. But it’s tricky business to allocate resources in a way that makes the most of the existing products, services and business models yet accomplishes what’s needed to create the future.

How a company allocates its resources defines its strategy. But it’s tricky business to allocate resources in a way that makes the most of the existing products, services and business models yet accomplishes what’s needed to create the future.

To strike the right balance, and before any decisions on specific projects, allocate the desired spending into three buckets – short, medium and long. Or, if you prefer, Horizon 1, 2 and 3. Use the business objectives to set the weighting. Then, sit next to the CFO for a couple days and allocate last year’s actual spending to the three buckets and compare the actuals with how resources will be allocated going forward. Define the number of people who will work on short, medium and long and how many will move from one bucket to another.

To get the balance right, short term projects are judged relative to short term projects, medium term projects are judged relative to medium term projects and the long term ones are judged against their long term peers. Long term projects cannot be staffed at the expense of short term projects and medium term projects cannot take resources from long term projects. To get the balance right, those are the rules.

To choose the best projects within each bucket, clarity and constraints are more important than ROI. Here are some questions to improve clarity and define the constraints.

How will the customer benefit? It’s best to show the customer using the product or service or experiencing the new business model. Use a hand sketch and few, if any, words. Use one page.

How is it different? In the hand sketch above, draw the novel (different) elements in red.

Who is the new customer? Define where they live, the language they speak and how they get the job done today.

Are there regional constraints? Infrastructure gaps, such as electricity, water, transportation are deal breakers. Language gaps can be big problems, so can regulatory, legal and cultural constraints. If a regional constraint cannot be overcome, do something else.

How will your company make money? Use this formula: (price – cost) x volume. But, be clear about the size of the market today and the size it could be in five years.

How will you make, sell and service it? Include in the cost of the project the cost to overcome organizational capacity/capability constraints. If cost (or time) to close the gaps is prohibitive, do something else.

How will the business model change? If it won’t, strongly consider a different project.

If the investigations show the project is worthwhile, how would you staff the project and when? This is an important one. If the project would be a winner, but there is no one to work on it, do something else. Or, consider stopping a bad project to start the good one.

There’s usually a general tendency to move medium term resources to short term projects and skimp on long term projects. Be respectful of the newly-minted resource balance defined at the start and don’t choose a project from one bucket over a project from another. And don’t get carried away with ROI measured to three significant figures, rather, hold onto the fact that an insurmountable constraint reduces ROI to zero.

And staff projects fully. Partially-staffed projects set expectations that good things are happening, but they never come to be.

Image credit – john curley

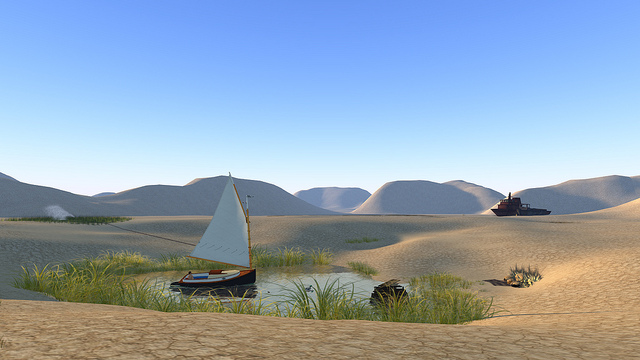

Channel your inner sea captain.

When it’s time for new work, the best and smartest get in a small room to figure out what to do. The process is pretty simple: define a new destination, and, to know when they journey is over, define what it looks like to live there. Define the idealized future state and define the work to get there. Turn on the GPS, enter the destination and follow the instructions of the computerized voice.

When it’s time for new work, the best and smartest get in a small room to figure out what to do. The process is pretty simple: define a new destination, and, to know when they journey is over, define what it looks like to live there. Define the idealized future state and define the work to get there. Turn on the GPS, enter the destination and follow the instructions of the computerized voice.

But with new work, the GPS analogy is less than helpful. Because the work is new, there’s no telling exactly where the destination is, or whether it exists at all. No one has sold a product like the one described in the idealized future state. At this stage, the product definition is wrong. So, set your course heading for South America though the destination may turn out to be Europe. No matter, it’s time to make progress, so get in the car and stomp the accelerator.

But with new work there is no map. It’s never been done before. Though unskillful, the first approach is to use the old map for the new territory. That’s like using map data from 1928 in your GPS. The computer voice will tell you to take a right, but that cart path no longer exists. The GPS calls out instructions that don’t match the street signs and highway numbers you see through the windshield. When the GPS disagrees with what you see with your eyeballs, the map is wrong. It’s time to toss the GPS and believe the territory.

With new work, it’s not the destination that’s important, the current location is most important. The old sea captains knew this. Site the stars, mark the time, and set a course heading. Sail for all your worth until the starts return and as soon as possible re-locate the ship, set a new heading and repeat. The course heading depends more on location than destination. If the ship is east of the West Indies, it’s best to sail west, and if the ship is to the north, it’s best to sail south. Same destination, different course heading.

When the work is new, through away the old maps and the GPS and channel your inner sea caption. Position yourself with the stars, site the landmarks with your telescope, feel the wind in your face and use your best judgement to set the course heading. And as soon as you can, repeat.

Image credit – Timo Gufler.

Stop bad project and start good ones.

At the most basic level, business is about allocating resources to the best projects and executing those projects well. Said another way, business is about deciding what to work on and then working effectively. But how to go about deciding what to work on? Here is a cascade of questions to start you on your journey.

At the most basic level, business is about allocating resources to the best projects and executing those projects well. Said another way, business is about deciding what to work on and then working effectively. But how to go about deciding what to work on? Here is a cascade of questions to start you on your journey.

What are your company’s guiding principles? Why does it exist? How does it want to go about its life? These questions create context from which to answer the questions that follow. Once defined, all your actions should align with your context.

How has the business environment changed? This is a big one. Everything is impermanent. Change is the status quo. What worked last time won’t work this time. Your success is your enemy because it stunts intentions to work on new things. Define new lines of customer goodness your competitors have developed; define how their technologies have increased performance; search YouTube to see the nascent technologies that will displace you; put yourself two years in the future where your customers will pay half what they pay today. These answers, too, define the context for the questions that follow.

What are you working on? Define your fully-staffed projects. Distill each to a single page. Do they provide new customer value? Are the projects aligned with your company’s guiding principles? For those that don’t, stop them. How do your fully-staffed projects compare to the trajectory of your competitors’ offerings? For those that compare poorly, stop them.

For projects that remain, do they meet your business objectives? If yes, put your head down and execute. If no, do you have better projects? If yes, move the freed up resources (from the stopped projects) onto the new projects. Do it now. If you don’t have better projects, find some. Use lines of evolution for technological systems to figure out what’s next, define new projects and move the resources. Do it now.

The best leading indicator of innovation is your portfolio of fully-staffed projects. Where other companies argue and complain about organizational structure, move your best resources to your best projects and execute. Where other companies use politics to trump logic, move your best resources to your best projects and execute. Where other successful companies hold on to tired business models and do-what-we-did-last-time projects, move your best resources to your best projects and execute.

Be ruthless with your projects. Stop the bad ones and start some good ones. Be clear about what your projects will deliver – define the novel customer value and the technical work to get there. Use one page for each. If you can’t define the novel customer value with a simple cartoon, it’s because there is none. And if you can’t define how you’ll get there with a hand sketch, it’s because you don’t know how.

Define your company’s purpose and use that to decide what to work on. If a project is misaligned, kill it. If a project is boring, don’t bother. If it’s been done before, don’t do it. And if you know how it will go, do something else.

If you’re not changing, you’re dying.

Image credit – David Flam

The Chief Innovation Mascot

I don’t believe the role of Chief Innovation Officer has a place in today’s organizations. Today, it should be about doing the right new work to create value. That work, I believe, should be done within the organization as a whole or within dedicated teams within the organization. That work, I believe, cannot be done by the Chief Innovation Officer because the organizational capability and capacity under their direct control is hollow.

I don’t believe the role of Chief Innovation Officer has a place in today’s organizations. Today, it should be about doing the right new work to create value. That work, I believe, should be done within the organization as a whole or within dedicated teams within the organization. That work, I believe, cannot be done by the Chief Innovation Officer because the organizational capability and capacity under their direct control is hollow.

Chief Innovation Officers don’t have the resources under their control to do innovation work. That’s the fundamental problem. Without the resources to invent, validate and commercialize, the Chief Innovation Officer is really the Chief Innovation Mascot- an advocate for the cause who wears the costume but doesn’t have direct control over the work.

Companies need to stop talking about innovation as a word and start doing the work that creates new products and services for new customers in markets. It all starts with the company’s business objectives (profitability goals) and an evaluation of existing projects to see if they’ll meet those objectives. If they will, then it’s about executing those projects. (The Chief Innovation Officer can’t help here because that requires operational resources.) If they won’t, it’s about defining and executing new projects that deliver new value to new customers. (Again, this is work for deep subject matter experts across multiple organizations, none of which work for the Chief Innovation Officer.)

To create a non-biased view of the projects, identify lines of customer goodness, measure the rate of change of that goodness, assess the underpinning technologies (momentum, trajectory, maturity and completeness) and define the trajectory of the commercial space. This requires significant resource commitments from marketing, engineering and sales, resource commitments The Chief Innovation Officer can’t commit. Cajole and prod for resources, yes. Allocate them, no.

With a clear-eyed view of their projects and the new-found realization that their projects won’t cut it, companies can strengthen their resolve to do new work in new ways. The realization of an immanent shortfall in profits is the only think powerful enough to cause the company to change course. The company then spends the time to create new projects and (here’s the kicker) moves resources to the new projects. The most articulate and persuasive Chief Innovation Officer can’t change an organization’s direction like that, nor can they move the resources.

To me it’s not about the Chief Innovation Officer. To me it’s about creating the causes and conditions for novel work; creating organizational capability and capacity to do the novel work; and applying resources to the novel work so it’s done effectively. And, yes, there are tools and methods to do that work well, but all that is secondary to allocating organizational capacity to do new work in new ways.

When Chief Innovation Officer are held accountable for “innovation objectives,” they fail because they’re beholden to the leaders who control the resources. (That’s why their tenures are short.) And even if they did meet the innovation objectives, the company would not increase it’s profits because innovation objectives don’t pay the bills. The leaders that control the resources must be held accountable for profitability objectives and they must be supported along the way by people that know how to do new work in new ways.

Let’s stop talking about innovation and the officers that are supposed to do it, and let’s start talking about new products and new services that deliver new value to new customers in new markets.

Image credit – Neon Tommy

Dissent Without Reprisal – a key to company longevity

In strategic planning there’s a strong forcing function that causes the organization to converge on a singular, company-wide approach. While this convergence can be helpful, when it’s force is absolute it stifles new ideas. The result is an operating plan that incrementally improves on last year’s work at the expense of work that creates new businesses, sells to new customers and guards against the dark forces of disruptive competition. In times of change convergence must be tempered to yield a bit of diversity in the approach. But for diversity to make it into the strategic plan, dissent must be an integral (and accepted) part of the planning process. And to inject meaningful diversity the dissenting voice must be as load as the voice of convergence.

In strategic planning there’s a strong forcing function that causes the organization to converge on a singular, company-wide approach. While this convergence can be helpful, when it’s force is absolute it stifles new ideas. The result is an operating plan that incrementally improves on last year’s work at the expense of work that creates new businesses, sells to new customers and guards against the dark forces of disruptive competition. In times of change convergence must be tempered to yield a bit of diversity in the approach. But for diversity to make it into the strategic plan, dissent must be an integral (and accepted) part of the planning process. And to inject meaningful diversity the dissenting voice must be as load as the voice of convergence.

It’s relatively easy for an organization to come to consensus on an idea that has little uncertainty and marginal upside. But there can be no consensus, but on an idea with a high degree of uncertainty even if the upside is monumental. If there’s a choice between minimizing uncertainty and creating something altogether new, the strategic process is fundamentally flawed because the planning group will always minimize uncertainty. Organizationally we are set up to deliver certainty, to make our metrics and meet our timelines. We have an organizational aversion to uncertainty, and, therefore, our organizational genetics demand we say no to ideas that create new business models, new markets and new customers. What’s missing is the organizational forcing function to counterbalance our aversion to uncertainty with a healthy grasping of it. If the company is to survive over the next 20 years, uncertainty must be injected into our organizational DNA. Organizationally, companies must be restructured to eliminate the choice between work that improves existing products/services and work that creates altogether new markets, customers, products and services.

When Congress or the President wants to push their agenda in a way that is not in the best long term interest of the country, no one within the party wants to be the dissenting voice. Even if the dissenting voice is right and Congress and the President are wrong, the political (career) implications of dissent within the party are too severe. And, organizationally, that’s why there’s a third branch of government that’s separate from the other two. More specifically, that’s why Justices of the Supreme Court are appointed for life. With lifetime appointments their dissenting voice can stand toe-to-toe with the voice of presidential and congressional convergence. Somehow, for long-term survival, companies must find a way to emulate that separation of power and protect the work with high uncertainty just as the Justices protect the law.

The best way I know to protect work with high uncertainty is to create separate organizations with separate strategic plans, operating plans and budgets. In that way, it’s never a decision between incremental improvement and discontinuous improvement. The decision becomes two separate decisions for two separate teams: Of the candidate projects for incremental improvement, which will be part of team A’s plan? And, of the candidate projects for discontinuous improvement, which will become part of team B’s plan?

But this doesn’t solve the whole challenge because at the highest organizational level, the level that sits above Team A and B, the organizational mechanism for dissent is missing. At this highest level there must be healthy dissent by the board of directors. Meaningful dissent requires deep understanding of the company’s market position, competitive landscape, organizational capability and capacity, the leading technology within the industry (the level, completeness and maturity), the leading technologies in adjacent industries and technologies that transcend industries (i.e., digital). But the trouble is board members cannot spend the time needed to create deep understanding required to formulate meaningful dissent. Yes, organizationally the board of directors can dissent without reprisal, but they don’t know the business well enough to dissent in the most meaningful way.

In medieval times the jester was an important player in the organization. He entertained the court but he also played the role of the dissenter. Organizationally, because the king and queen expected the jester to demonstrate his sharp wit, he could poke fun at them when their ideas didn’t hang together. He could facilitate dissent with a humorous play on a deadly serious topic. It was delicate work, as one step too far and the jester was no more. To strike the right balance the jester developed deep knowledge of the king, queen and major players in the court. And he had to know how to recognize when it was time to dissent and when it was time to keep his mouth shut. The jester had the confidence of the court, knew the history and could see invisible political forces at play. The jester had the organizational responsibility to dissent and the deep knowledge to do it in a meaningful way.

Companies don’t need a jester, but they do need a T-shaped person with broad experience, deep knowledge and the organizational status to dissent without reprisal. Maybe this is a full time board member or a hired gun that works for the board (or CEO?), but either way they are incentivized to dissent in a meaningful way.

I don’t know what to call this new role, but I do know it’s an important one.

Image credit – Will Montague

Is the new one better than the old one?

Successful commercialization of products and services is fueled by one fundamental – making the new one better than the old one. If the new one is better the customer experience is better, the marketing is better, the sales are better and the profits are better.

Successful commercialization of products and services is fueled by one fundamental – making the new one better than the old one. If the new one is better the customer experience is better, the marketing is better, the sales are better and the profits are better.

It’s not enough to know in your heart that the new one is better, there’s got to be objective evidence that demonstrates the improvement. The only way to do that is with testing. There are a number of types testing mechanisms, but whether it’s surveys, interviews or in-the-lab experiments, test results must be quantifiable and repeatable.

The best way I know to determine if the new one is better than the old one is to test both populations with the same test protocol done on the same test setup and measure the results (in a quantified way) using the same measurement system. Sounds easy, but it’s not. The biggest mistake is the confusion between the “same” test conditions and “almost the same” test conditions. If the test protocol is slightly different there’s no way to tell if the difference between new and old is due to goodness of the new design or the badness of the test setup. This type of uncertainty won’t cut it.

You can never be 100% sure that new one is better than the old one, but that’s were statistics come in handy. Without getting deep into the statistics, here’s how it goes. For both population’s test results the mean and standard deviation (spread) are calculated, and taking into consideration the sample size of the test results, the statistical test will tell you if they’re different and confidence of it’s discernment.

The statistical calculations (Student’s t-test) aren’t all that important, what’s important is to understand the implications of the calculations. When there’s a small difference between new and old, the sample size must be large for the statistics to recognize a difference. When the difference between populations is huge, a sample size of one will do nicely. When the spread of the data within a population is large, the statistics need a large sample size or it can’t tell new from old. But when the data is tight, they can see more clearly and need fewer samples to see a difference.

If marketing claims are based on large sample sizes, the difference between new and old is small. (No one uses large sample sizes unless they have to because they’re expensive.) But if in a design review for the new product the sample size is three and the statistical confidence is 95%, new is far better than old. If the average of new is much larger than the average of old and the sample size is large yet the confidence is low, the statistics know the there’s a lot of variability within the populations. (A visual check should show the distributions to more wide than tall.)

The measurement systems used in the experiments can give a good indication of the difference between new and old. If the measurement system is expensive and complicated, likely the difference between new and old is small. Like with large sample sizes, the only time to use an expensive measurement system is when it is needed. And when the difference between new and old is small, the expensive measurement system’s ability accurately and repeatably measure small differences (micrometers vs. meters).

If you need large sample sizes, expensive measurement systems and complicated statistical analyses, the new one isn’t all that different from the old one. And when that’s the case, your new profits will be much like your old ones. But if your naked eye can see the difference with a back-to-back comparison using a sample size of one, you’re on to something.

Image credit – amanda tipton

If you don’t know the critical path, you don’t know very much.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Two words to live by: Critical Path.

By definition, the next task to work on is the next task on the critical path. How do you tell if the task is on the critical path? When you are late by one day on a critical path task, the project, as a whole, will finish a day late. If you are late by one day and the project won’t be delayed, the task is not on the critical path and you shouldn’t work on it.

Rule 1: If you can’t work the critical path, don’t work on anything.

Working on a non-critical path task is worse than working on nothing. Working on a non-critical path task is like waiting with perspiration. It’s worse than activity without progress. Resources are consumed on unnecessary tasks and the resulting work creates extra constraints on future work, all in the name of leveraging the work you shouldn’t have done in the first place.

How to spot the critical path? If a similar project has been done before, ask the project manager what the critical path was for that project. Then listen, because that’s the critical path. If your project is similar to a previous project except with some incremental newness, the newness is on the critical path.

Rule 2: Newness, by definition, is on the critical path.

But as the level of newness increases, it’s more difficult for project managers to tell the critical path from work that should wait. If you’re the right project manager, even for projects with significant newness, you are able to feel the critical path in your chest. When you’re the right project manager, you can walk through the cubicles and your body is drawn to the critical path like a divining rod. When you’re the right project manager and someone in another building is late on their critical path task, you somehow unknowingly end up getting a haircut at the same time and offering them the resources they need to get back on track. When you’re the right project manager, the universe notifies you when the critical path has gone critical.

Rule 3: The only way to be the right project manager is to run a lot of projects and read a lot. (I prefer historical fiction and biographies.)

Not all newness is created equal. If the project won’t launch unless the newness is wrestled to the ground, that’s level 5 newness. Stop everything, clear the decks, and get after it until it succumbs to your diligence. If the product won’t sell without the newness, that’s level 5 and you should behave accordingly. If the newness causes the product to cost a bit more than expected, but the project will still sell like nobody’s business, that’s level 2. Launch it and cost reduce it later. If no one will notice if the newness doesn’t make it into the product, that’s level 0 newness. (Actually, it’s not newness at all, it’s unneeded complexity.) Don’t put in the product and don’t bother telling anyone.

Rule 4: The newness you’re afraid of isn’t the newness you should be afraid of.

A good project plan starts with a good understanding of the newness. Then, the right project work is defined to make sure the newness gets the attention it deserves. The problem isn’t the newness you know, the problem is the unknown consequence of newness as it ripples through the commercialization engine. New product functionality gets engineering attention until it’s run to ground. But what if the newness ripples into new materials that can’t be made or new assembly methods that don’t exist? What if the new materials are banned substances? What if your multi-million dollar test stations don’t have the capability to accommodate the new functionality? What if the value proposition is new and your sales team doesn’t know how to sell it? What if the newness requires a new distribution channel you don’t have? What if your service organization doesn’t have the ability to diagnose a failure of the new newness?

Rule 5: The only way to develop the capability to handle newness is to pair a soon-to-be great project manager with an already great project manager.

It may sound like an inefficient way to solve the problem, but pairing the two project managers is a lot more efficient than letting a soon-to-be great project manager crash and burn. After an inexperienced project manager runs a project into the ground, what’s the first thing you do? You bring in a great project manager to get the project back on track and keep them in the saddle until the product launches. Why not assume the wheels will fall off unless you put a pro alongside the high potential talent?

Rule 6: When your best project managers tell you they need resources, give them what they ask for.

If you want to deliver new value to new customs there’s no better way than to develop good project managers. A good project manager instinctively knows the critical path; they know how the work is done; they know to unwind situations that needs to be unwound; they have the personal relationships to get things done when no one else can; because they are trusted, they can get people to bend (and sometimes break) the rules and feel good doing it; and they know what they need to successfully launch the product.

If you don’t know your critical path, you don’t know very much. And if your project managers don’t know the critical path, you should stop what you’re doing, pull hard on the emergency break with both hands and don’t release it until you know they know.

Image credit – Patrick Emerson

Organized For Uncertainty

There are many different organizational structures, each with its unique set of strengths and weaknesses. The top-down organization has its strong alignment and limited flexibility while the bottom-up has its empowering consensus and sloth-like pace. Which one’s better? Well, it depends.

There are many different organizational structures, each with its unique set of strengths and weaknesses. The top-down organization has its strong alignment and limited flexibility while the bottom-up has its empowering consensus and sloth-like pace. Which one’s better? Well, it depends.

The function-based organization has strong subject matter expertise and weak cross-function coordination, while the business unit-based organization knows its product, market and customers but has difficulty working east-west across product families and customer segments. Is one better than the other? Same answer- it depends.

The matrix organization has the best of both worlds – business unit and functional – and isn’t particularly good at either. And there’s the ambidextrous organization that I don’t pretend to understand. If I had to choose one, which would I choose? It depends.

The best organizational structure depends on what you’re trying to do, depends on the environmental context, depends on the organization’s history and biases and the general state of organizational capability, capacity and profitability. But that’s not the whole picture because none of this is static. All of this changes over time and it changes in an unpredictable way. Because the best organizational structure depends on all these complicating factors and the factors change over time, there is never a “best” organizational structure.

Constant change has always been the dominant fundamental perturbing and disturbing our organizational structures. But, as competition turns up the wick and the pace of learning builds geometrically, change’s ability to influence our organizational structures has grown from disturbing to dismantling.

Change is the dominant fundamental, but its real power comes from the uncertainty it brings to the party. Our tired, old organizational structures were designed to survive in a long-dead era of glacial change and rationed uncertainty. And though our organizational structures were built in granite, the elevated sea levels of uncertainty are creating fissures in our inflexible organizational structures and profitability is leaking from all levels

If uncertainty is the disease, adaptability is the antidote. The organization must continually monitor its environment for changes. And when it senses an emerging shift, the organization it must move resources in a way that satisfies the new reality. The organization structure shifts to fit the work. The structure changes as the character of the projects change. The organizational structure never reaches equilibrium; it survives through continual evolutionary loop of sense-change-sense.

I don’t have a name for an organization like this, and I think it’s best not to name it. Instead, I think it’s best to describe how it behaves. It’s a living organization that behaves like a living organism. It wants to survive, so it changes itself based on changes in its environment. It’s an organization that self organizes.

Directionally, organizational structures should be less static and more dynamic, and they should evolve to fit the work. The difficult part is how to define the explicit rules on how it should change, when it should change and how it decides. But it’s more than difficult to describe explicit rules, it’s impossible. In domains of high levels of uncertainty there can be no predictability and without predictability a finite set of explicit rules will not work. The DNA of this living organization is implicit knowledge, evolutionary experimentation and personal judgement.

I’m not sure what to call this type of organizational structure, and I’m not exactly sure how to create one. But it sure sounds like a lot of fun.

Image credit — actor212

Battling the Dark Arts of Productivity and Accountability

How did you get to where you are? Was it a series of well-thought-out decisions or a million small, non-decisions that stacked up while you weren’t paying attention? Is this where you thought you’d end up? What do you think about where you are?

How did you get to where you are? Was it a series of well-thought-out decisions or a million small, non-decisions that stacked up while you weren’t paying attention? Is this where you thought you’d end up? What do you think about where you are?

It takes great discipline to make time to evaluate your life’s trajectory, and with today’s pace it’s almost impossible. Every day it’s a battle to do more than yesterday. Nothing is good enough unless it’s 10% better than last time, and once it’s better, it’s no longer good enough. Efficiency is worked until it reaches 100%, then it’s redefined to start the game again. No waste is too small to eliminate. In business there’s no counterbalance to the economists’ false promise of never-ending growth, unless you provide it for yourself.

If you make the time, it’s easy to plan your day and your week. But if you don’t make the time, it’s impossible. And it’s the same for the longer term – if you make the time to think about what you want to achieve, you have a better chance of achieving it – but it’s more difficult to make the time. Before you can make the time to step back and take look at the landscape, you’ve got to be aware that it’s important to do and you’re not doing it.

Providing yourself the necessary counterbalance is good for you and your family, and it’s even better for business. When you take a step back and slow your pace from sprint to marathon, you are happier and healthier and your work is better. When scout the horizon and realize you and your work are aligned, you feel better about the work and, therefore, you feel better about yourself. You’re a better person, partner and parent. And your work is better. When the work fits, everything is better.

Sometimes, people know their work doesn’t fit and purposefully don’t take a step back because it’s too scary to acknowledge there’s a problem. But burying your head doesn’t fix things. If you know you’re out of balance, the best thing to do is admit it and start a dialog with yourself and your boss. It won’t get better immediately, but you’ll feel better immediately. But most of the time, people don’t make time to take a step back because of the blistering pace of the work. There’s simply no time to think about the future. What’s missing is a weapon to battle the black arts of productivity and accountability.

The only thing powerful enough to counterbalance the forces of darkness is the very weapon we use to create the disease of hyper-productivity – the shared calendar (MS Calendar, Google Calendar). Open up the software, choose your day, choose your time and set up a one hour weekly meeting with yourself. Attendees: you. Agenda: take a couple deep breaths, relax and think. Change your settings so no one can see the meeting title and agenda and choose the color that makes people think the meeting is off-site. With your time blocked, you now have a reason to say no to other meetings. “Sorry, I can’t attend. I have a meeting.”

This simple mechanism is all you need.

No more excuses. Make the time for yourself. You’re worth it.

image credit :jovian (image modified)

Patents are supposed to improve profitability.

Everyone likes patents, but few use them as a business tool.

Everyone likes patents, but few use them as a business tool.

Patents define rights assigned by governments to inventors (really, the companies they work for) where the assignee has the right to exclude others from practicing the concepts described in the patent claims. And patent rights are limited to the countries that grant patents. If you want to get patent rights in a country, you submit your request (application) and run their gauntlet. Patents are a country-by-country business.

Patents are expensive. Small companies struggle to justify the expense of filing a single patent and big companies struggle to justify the expense of their portfolio. All companies want to reduce patent costs.

The patent process starts with invention. Someone must go to the lab and invent something. The invention is documented by the inventor (invention disclosure) and the invention is scored by a cross-functional team to decide if it’s worthy of filing. If deemed worthy, a clearance search is done to see if it’s different from all other patents, all products offered for sale, and all the other literature in the public domain (research papers, publications). Then, then the patent attorneys work their expensive magic to draft a patent application and file it with the government of choice. And when the rejection arrives, the attorneys do some research, address the examiner’s concerns and submit the paperwork.

Once granted, the fun begins. The company must keep watch on the marketplace to make sure no one sells products that use the patented technology. It’s a costly, never-ending battle. If infringement is suspected, the attorneys exchange documents in a cease-and-desist jousting match. If there’s no resolution, it’s time to go to court where prosecution work turns up the burn rate to eleven.

To reduce costs, companies try to reduce the price they pay to outside law firms that draft their patents. It’s a race to the bottom where no one wins. Outside firms get paid less money per patent and the client gets patents that aren’t as good as they could be. It’s a best practice, but it’s not best. Treating patent work as a cost center isn’t right. Patents are a business tool that help companies make money.

Companies are in business to make money and they do that by selling products for more than the cost to make them. They set clear business objectives for growth and define the market-customers to fuel that growth. And the growth is powered by the magic engine of innovation. Innovation creates products/services that are novel, useful and successful and patents protect them. That’s what patents do best and that’s how companies should use them.

If you don’t have a lot of time and you want to understand a patent, read the claims. If you have less time, read the independent claims. Chris Brown, Ph.D.

Patents are all about claims. The claims define how the invention is different (novel) from what’s tin the public domain (prior art). And since innovation starts with different, patents fit nicely within the innovation framework. Instead of trying to reduce patent costs, companies should focus on better claims, because better claims means better patents. Here are some thoughts on what makes for good claims.

Patent claims should capture the novelty of the invention, but sometimes the words are wrong and the claims don’t cover the invention. And when that happens, the patent issues but it does not protect the invention – all the downside with none of the upside. The best way to make sure the claims cover the invention is for the inventor to review the claims before the patent is filed. This makes for a nice closed-loop process.

When a novel technology has the potential to provide useful benefit to a customer, engineers turn those technologies into prototypes and test them in the lab. Since engineers are minimum energy creatures and make prototypes for only the technologies that matter, if the patent claims cover the prototype, those are good claims.

When the prototype is developed into a product that is sold in the market and the novel technology covered by the claims is what makes the product successful, those are good claims.

If you were to remove the patented technology from the product and your customer would notice it instantly and become incensed, those are the best claims.

Instead of reducing the cost of patents, create processes to make sure the right claims are created. Instead of cutting corners, embed your patent attorneys in the technology development process to file patents on the most important, most viable technology. Instead of handing off invention disclosures to an isolated patent team, get them involved in the corporate planning process so they understand the business objectives and operating plans. Get your patent attorneys out in the field and let them talk to customers. That way they’ll know how to spot customer value and write good claims around it.

Patents are an important business tool and should be used that way. Patents should help your company make money. But patents aren’t the right solution to all problems. Patent work can be slow, expensive and uncertain. A more powerful and more certain approach is a strong investment in understanding the market, ritualistic technology development, solid commercialization and a relentless pursuit of speed. And the icing on the top – a slathering of good patent claims to protect the most important bits.

Image credit – Matthais Weinberger

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski