Archive for the ‘Fear’ Category

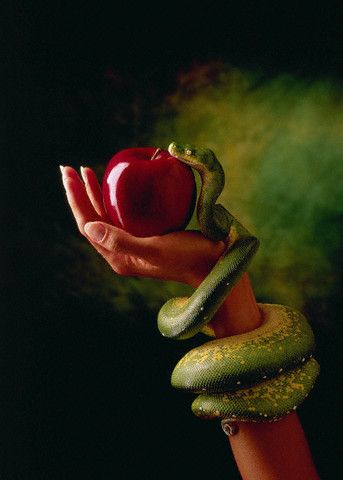

The Forbidden Fruit of Failure

We’ve mapped failure to the wrong words. And this mis-mapping is so strong and deep that un-mapping seems unlikely. I propose failure, as a word, be scratched from the dictionary.

We’ve mapped failure to the wrong words. And this mis-mapping is so strong and deep that un-mapping seems unlikely. I propose failure, as a word, be scratched from the dictionary.

Failure is learning in the form of experiments (including the thought kind) with outcomes different than theorized, where the outcomes create a more complete understanding of theory, or learning.

Wrong is mapped to failure, but failure should be mapped with – different than our best understanding.

Newness is mapped to failure. Replace failure with learning and the mapping is right – more newness, more learning. This is why tolerance of failure (and newness) is a must – no newness, no failure, no learning.

Risk is mapped to failure. Replace failure with learning and the mapping is right – more risk, more learning. Risk cannot be forbidden, if we’re to learn.

Risk and newness are mapped to late, and, guilt by association, failure is mapped to late. Replace failure with learning and the mapping is right – learn fast to avoid being late. And now, after several paragraphs of un-mapping, hopefully the re-substitution makes sense – fail fast to avoid being late.

Failure isn’t failure, failure is learning.

Creativity’s Mission Impossible

Whether it’s a top-down initiative or a bottom-up revolution, your choice will make or break it.

Whether it’s a top-down initiative or a bottom-up revolution, your choice will make or break it.

When you have the inspiration for a bottom-up revolution, you must be brave enough to engage your curiosity without self-dismissing. You’ll feel the automatic urge to self-reject – that will never work, too crazy, too silly, too loony – but you must resist. (Automatic self-rejection is the embodiment of your fear of failure.) At all costs you must preserve the possibility you’ll try the loony idea; you must preserve the opportunity to learn from failure; you must suspend judgment.

Now it’s time to tell someone your new thinking. Summon the next level of courage, and choose wisely. Choose someone knowledgeable and who will be comfortable when you slather them with the ambiguity. (No ambiguity, no new thinking.) But most importantly, choose someone who will suspend judgment.

You now have critical mass – you, your partner in crime, and your bias for action. Together you must prevent the new thinking from dying on the vine. Tell no one else, and try it. Try it at a small scale, try it in your garage. Fail-learn-fail until you have something with legs. Don’t ask. Suspend judgment, and do.

And what of top down initiatives? They start with bottom-up new thinking, so the message is the same: suspend judgment, engage your bias for action, and try it. This is the precursor to the thousand independent choices that self-coordinate into a top-down initiative.

New thinking is a choice, and turning it into action is another. But this is your mission, if you choose to accept it.

I will be holding a half-day Workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment on June 13 in RI. (See bottom of linked page.) I look forward to meeting you in person.

Choose Your Path

There are only three things you can do:

There are only three things you can do:

1. Do what you’re told. This is fine once in a while, but not fine if you’re also told how.

2. Do what you’re not told. This is the normal state of things – good leaders let good people choose.

3. Do what you’re told not to. This is rarified air, but don’t rule it out.

Run From Your Success

Don’t worry about your biggest competitor – they’re not your biggest competitor. You’ve not met your biggest competitor. Your biggest competitor is either from another industry or it’s three guys and a dog toiling away in their basement.

Don’t worry about your biggest competitor – they’re not your biggest competitor. You’ve not met your biggest competitor. Your biggest competitor is either from another industry or it’s three guys and a dog toiling away in their basement.

Certainly it’s impossible to worry about a competitor we’ve not met, but that’s just what we’ve got to do. We’ve got to use thought-shifting mechanisms to help us see ourselves from the framework of our unknown competitor.

Our unknown competitor doesn’t have much – no fully functional products, no fully built-out product lines, and no market share. And that’s where we must shift our thinking – to a place of scarcity – so we can see ourselves from their framework. We’ve got to look down (in the S-curve sense), sit ourselves at the bottom, and look up at our successful selves. It’s the best way to move from self-cherishing to self-dismantling.

To start, we must create our logical trajectory. First, define where we are and where we came from. Then, with a ruler aligned to the points, extend a line into the future. That’s our logical trajectory – an extrapolation in the direction of our success. Along this line we will do more of what got us here, more of what we’ve done. Without giving ground on any front, we will protect market share and build more. We’ve now defined how we see ourselves. We’ve now defined the thinking that could be our undoing.

Now we must force enlightenment on ourselves. We create an illogical trajectory where we see ourselves from a success-less framework. In this framework less is more; more-of-the-same is displaced with more-of-something-else; and success is a weakness. We know we’re sitting in the rights space when the smallest slice of incremental market share looks like a big, juicy bite – like it looks to our unknown competitor.

The disruptive technology created by our unknown competitor will start innocently. Immature at first, the disruptive technology will do most things poorly but do one thing better. Viewed from our success framework we will see only limitations and dismiss it, while our unknown competitors will see opportunity. We will see the does-most-things-poorly part and they’ll see the one-thing-better part. They will sell to a small segment that values the one-thing-better part.

In another variant, an immature disruptive technology will do less with far less. From our success framework we will see “less” while from their scarcity framework they will see “more”. They will sell a simpler product that does less for a price that’s far less. (And make money.)

Here’s the one that’s most frightening: an immature technology that does all things poorly but does them without a fundamental limitation of our technology. From our framework the limitation is so fundamental we won’t let ourselves see it. This limitation is un-seeable because we’ve built our business around it. (Think Kodak film.) This flavor of disruptive technology can put our business model out of business, yet we’ll dismiss it.

We’ll know we’ve shifted our thinking to the right place when we see our unknown competitors not as bottom-feeders but as hungry competitors who see our scraps as a smorgasbord.

We’ll know our thinking’s right when see not self-destruction, but self-disruption.

We’ll know all is right with the world we’re working on disruptive technologies to disrupt ourselves, disruptive technologies with the potential to create business models so compelling that we’ll gladly run from our success.

Can’t Say NO

- Yes is easy, no is hard.

- Sometimes slower is faster.

- Yes, and here’s what it will take:

- The best choose what they’ll not do.

- Judge people on what they say no to.

- Work and resources are a matched pair.

- Define the work you’ll do and do just that.

- Adding scope is easy, but taking it out is hard.

- Map yes to a project plan based on work content.

- Challenge yourself to challenge your thinking on no.

- Saying yes to something means saying no to something else.

- The best have chosen wrong before, that’s why they’re the best.

- It’s better to take one bite and swallow than take three and choke.

Be Your Stiffest Competitor

Your business is going away. Not if, when. Someone’s going to make it go away and it might as well be you. Why not take control and make it go away on your own terms? Why not make it go away and replace it with something bigger and better?

Your business is going away. Not if, when. Someone’s going to make it go away and it might as well be you. Why not take control and make it go away on your own terms? Why not make it go away and replace it with something bigger and better?

Success is good, but fleeting. Like a roller coaster with up-and-up clicking and clacking, there’s a drop coming. But with a roller coaster we expect it – there’s always a drop. (That’s what makes it a roller coaster.) We get ready for it, we brace ourselves. Half-scared and half-excited, electricity fills us, self-made fight-or-flight energy that keeps us safe. I think success should be the same – we should expect the drop.

More strongly we should manage the drop, make it happen on our terms. But that’s going to be difficult. Success makes it easy to unknowingly slip into protecting-what-we-have mode. If we’re to manage the drop, we must learn to relish it like the roller coaster. As we’re ascending – on the way up – we must learn to create a healthy discomfort around success, like the sweaty-palm feeling of the roller coaster’s impending wild ride.

A sky-is-falling approach won’t help us embrace the drop. With success all around, even the best roller coaster argument will be overpowered. The argument must be based on positivity. Acknowledge success, celebrate it, and then challenge your organization to improve on it. Help your organization see today’s success as the foundation for the future’s success – like standing on the shoulders of giants. But in this case, the next level of success will be achieved by dismantling what you’ve built.

No one knows what the future will be, other than there will be increased competition. Hopefully, in the future, your stiffest competitor will be you.

Seeing Things As They Are

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

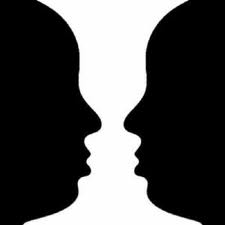

With the wicked couple of competition and profitability goals, we’re under a lot of pressure. And with the pressure comes the danger of seeing things how we want them instead of how they are, like a self-created optical illusion. Here are some likely optical illusion A-B pairs (A – how we want things; B – how they are):

A. Give people more work and more gets done. B. Human output has a physical limit, and once reached less gets done – and spouses get angry. A. Do more projects in parallel to generate more profit. B. Business processes have physical limits, and once reached projects slow and everyone works harder for the same output. A. Add resources to the core project team and more projects get done. B. Add resources to core projects teams and utilization skyrockets for shared resources – waiting time increases for all. A. Use lean in product development (just like in manufacturing) to launch new products better and faster. B. Lean done in product development is absolutely different than in manufacturing, and design engineers don’t take kindly to manufacturing folks telling them how to do their work. A. Through negotiation and price reduction, suppliers can deliver cost reductions year-on-year. B. The profit equation has a physical limit (no profit), and once reached there is no supplier. A. Use lean to reduce product cost by 5%. B. Use DFMA to reduce product cost by 50%.Competition is severe and the pressure is real. And so is the danger to see things as we want them to be. But there’s a simple way to see things as they are: ask the people that do the work. Go to the work and ask the experts. They do the work day-in-day-out, and they know what really happens. They know the details, the pinch points, and the critical interactions.

To see things as they are, check your ego at the door, and go ask the experts – the people that do the work.

When It’s Time For a New Cowpath

Doing new things doesn’t take a long time. What takes a long time is seeing things as they are. Getting ready takes time, not doing new. Awareness of assumptions, your assumptions, others’ assumptions, the company’s – that’s critical path.

Doing new things doesn’t take a long time. What takes a long time is seeing things as they are. Getting ready takes time, not doing new. Awareness of assumptions, your assumptions, others’ assumptions, the company’s – that’s critical path.

An existing design, product, service, or process looks as it does because of assumptions made during long ago for reasons no longer relevant (if they ever were). Design elements blindly carried forward, design approaches deemed gospel, scripted service policies that no longer make sense, awkward process steps proceduralized and rev controlled – all artifacts of old, unchallenged assumptions. And as they grow roots, assumptions blossom into constraints. Fertile design space blocked, new technologies squelched, new approaches laughed out of town – all in the name of constraints founded on wilted assumptions. And the most successful assumptions have the deepest roots and create the deepest grooves of behavior.

Cows do the same thing every day. They wake up at the same time (regardless of daylight savings), get milked at the same time, and walk the same path. They walk in such a repeatable way, they make cowpaths – neat grooves walked into the landscape – curiously curved paths with pre-made decisions. No cow worth her salt walks outside the cowpath. No need. Cows like to save their energy for making milk at the expense of making decisions. If it was the right path yesterday, it’s right today.

But how to tell when old assumptions limit more than they guide? How to tell when it’s time to step out of the groove? How to tell a perfectly good cowpath from one that leads to a dry watering hole? When is it time to step back and create new history? Long ago the first cow had to make a choice, and she did. She could have gone any which way, and she did. She made the path we follow today.

With blind acceptance of assumptions, we wither into bankruptcy, and with constant second-guessing we stall progress. We must strike a balance. We must hold healthy respect for what has worked and healthy disrespect for the status-quo. We must use forked-tongue thinking to pull from both ends. In a yin-yang way, we must acknowledge how we got here, and push for new thinking to create the future.

Trust is better than control.

Although it’s more important than ever, trust is in short supply. With everyone doing three jobs, there’s really no time for anything but a trust-based approach. Yet we’re blocked by the fear that trust means loss of control. But that’s backward.

Although it’s more important than ever, trust is in short supply. With everyone doing three jobs, there’s really no time for anything but a trust-based approach. Yet we’re blocked by the fear that trust means loss of control. But that’s backward.

Trust is a funny thing. If you have it, you don’t need it. If you don’t have it, you need it. If you have it, it’s clear what to do – just behave like you should be trusted. If you don’t have it, it’s less clear what to do. But you should do the same thing – behave like you should be trusted. Either way, whether you have it or not, behave like you should be trusted.

Trust is only given after you’ve behaved like you should be trusted. It’s paid in arrears. And people that should be trusted make choices. Whether it’s an approach, a methodology, a technology, or a design, they choose. People that should be trusted make decisions with incomplete data and have a bias for action. They figure out the right thing to do, then do it. Then they present results – in arrears.

I can’t choose – I don’t have permission. To that I say you’ve chosen not to choose. Of course you don’t have permission. Like trust, it’s paid in arrears. You don’t get permission until you demonstrate you don’t need it. If you had permission, the work would not be worth your time. You should do the work you should have permission to do. No permission is the same as no trust. Restating, I can’t choose – I don’t have trust. To that I say you’ve chosen not to choose.

There’s a misperception that minimizing trust minimizes risk. With our control mechanisms we try to design out reliance on trust – standardized templates, standardized process, consensus-based decision making. But it always comes down to trust. In the end, the subject matter experts decide. They decide how to fill out the templates, decided how to follow the process, and decide how consensus decisions are made. The subject matter experts choose the technical approach, the topology, the materials and geometries, and the design details. Maybe not the what, but they certainly choose the how.

Instead of trying to control, it’s more effective to trust up front – to acknowledge and behave like trust is always part of the equation. With trust there is less bureaucracy, less overhead, more productivity, better work, and even magic. With trust there is a personal connection to the work. With trust there is engagement. And with trust there is more control.

But it’s not really control. When subject matter experts are trusted, they seek input from project leaders. They know their input has value so they ask for context and make decisions that fit. Instead of a herd of cats, they’re a swarm of bees. Paradoxically, with a trust-based approach you amplify the good parts of control without the control parts. It’s better than control. It’s where ideas, thoughts and feelings are shared openly and respectfully; it’s where there’s learning through disagreement; it’s where the best business decisions are made; it’s where trust is the foundation. It’s a trust-based approach.

The Bottom-Up Revolution

The No. 1 reason initiatives are successful is support from top management. Whether it’s lean, Six Sigma, Design for Six Sigma or any program, top management support is vital. No argument. It’s easy with full support, but there’s never enough to go around.

The No. 1 reason initiatives are successful is support from top management. Whether it’s lean, Six Sigma, Design for Six Sigma or any program, top management support is vital. No argument. It’s easy with full support, but there’s never enough to go around.

But that’s the way it should be. Top management has a lot going on, much of it we don’t see: legal matters, business relationships, press conferences, the company’s future. If all programs had top management support, they would fail due to resource cannibalization. And we’d have real fodder for our favorite complaint—too many managers.

When there’s insufficient top management support, we have a choice. We can look outside and play the blame game. “This company doesn’t do anything right.” Or we can look inside and choose how we’ll do our work. It’s easy to look outside, then fabricate excuses to do nothing. It’s difficult to look inside, then create the future, especially when we’re drowning in the now. Layer on a new initiative, and frustration is natural. But it’s a choice.

We will always have more work than time….

How To Fix Product Development

The new product development process creates more value than any other process. And because of this it’s a logical target for improvement. But it’s also the most complicated business process. No other process cuts across an organization like new product development. Improvement is difficult.

The new product development process creates more value than any other process. And because of this it’s a logical target for improvement. But it’s also the most complicated business process. No other process cuts across an organization like new product development. Improvement is difficult.

The CEO throws out the challenge – “Fix new product development.” Great idea, but not actionable. Can’t put a plan together. Don’t know the problem. Stepping back, who will lead the charge? Whose problem is it?

The goal of all projects is to solve problems. And it’s no different when fixing product development – work is informed by problems. No problem, no fix. Sure you can put together one hell of a big improvement project, but there’s no value without the right problem. There’s nothing worse than spending lots of time on the wrong problem. And it’s doubly bad with product development because while fixing the wrong problem engineers are not working on the new products. Yikes.

Problems are informed by outcomes. Make a short list of desired outcomes and show the CEO. Your list won’t be right, but it will facilitate a meaningful discussion. Listen to the input, go back and refine the list, and meet again with the CEO. There will be immense pressure to start the improvement work, but resist. Any improvement work done now will be wrong and will create momentum in the wrong direction. Don’t move until outcomes are defined.

With outcomes in hand, get the band back together. You know who they are. You’ve worked with them over the years. They’re influential and seasoned. You trust them and so does the organization. In an off-site location show them the outcomes and ask them for the problems. (To get their best thinking spend money on great food and a relaxing environment.) If they’re the right folks, they’ll say they don’t know. Then, they’ll craft the work to figure it out – to collect and analyze the data. (The first part of problem definition is problem definition.) There will be immense pressure to start the improvement work, but resist. Any work done now will be wrong. Don’t move until problems are defined.

With outcomes and problems in hand, meet with the CEO. Listen. If outcomes change, get the band back together and repeat the previous paragraph. Then set up another meeting with the CEO. Review outcomes and problems. Listen. If there’s agreement, it’s time to put a plan together. If there’s disagreement, stop. Don’t move until there’s agreement. This is where it gets sticky. It’s a battle to balance everyone’s thoughts and feelings, but that’s your challenge. No words of wisdom on than – don’t move until outcomes and problems are defined.

There’s a lot of emotion around the product development process. We argue about the right way to fix it – the right tools, training, and philosophies. But there’s no place for argument. Analyze your process and define outcomes and problems. The result will be a well informed improvement plan and alignment across the company.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski