Archive for the ‘Culture’ Category

Work The Rule

If the rule makes things take too long, do you follow it or shortcut it?

If the rule makes things take too long, do you follow it or shortcut it?

If the reason for the rule is no longer, do you follow it or declare it unreasonable?

If you don’t understand the rule do you work to understand it, or conveniently trespass?

If you don’t follow the rule, does that say something about the rule, or you?

When is a rule a rule and when is it shackles?

When it comes to law, physics, and safety, a rule is a rule.

If you’re limited by the rule, is it bad? (Isn’t far worse if you don’t realize it?)

What if the solution demands unruliness?

If you don’t follow rules, is it okay to make them?

What if a culture is so strong it rules out most everything, except following the rules?

What if a culture is so strong it demands you make the rules?

When it comes to rules, there’s only one rule – You decide.

I will hold a Workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment on June 13 in RI. (See bottom of linked page.) I look forward to meeting you in person.

Win Hearts and Minds

As an engineering leader you have the biggest profit lever in the company. You lead the engineering teams, and the engineering teams design the products. You can shape their work, you can help them raise their game, and you can help them change their thinking. But if you don’t win their hearts and minds, you have nothing.

As an engineering leader you have the biggest profit lever in the company. You lead the engineering teams, and the engineering teams design the products. You can shape their work, you can help them raise their game, and you can help them change their thinking. But if you don’t win their hearts and minds, you have nothing.

Engineers must see your intentions are good, you must say what you do and do what you say, and you must be in it for the long haul. And over time, as they trust, the profit lever grows into effectiveness. But if you don’t earn their trust, you have nothing.

But even with trust, you must be light on the tiller. Engineers don’t like change (we’re risk reducing beings), but change is a must. But go too quickly, and you’ll go too slowly. You must balance praise of success with praise of new thinking and create a standing-on-the-shoulders-of-giants mindset. But this is a challenge because they are the giants – you’re asking them to stand on their own shoulders.

How do you know they’re ready for new thinking? They’re ready when they’re willing to obsolete their best work and to change their work to make it happen. Strangely, they don’t need to believe it’s possible – they only need to believe in you.

Now the tough part: There’s a lot of new thinking out there. Which to choose?

Whatever the new thinking, it must make sense at a visceral level, and it must be simple. (But not simplistic.) Don’t worry if you don’t yet have your new thinking; it will come. As a seed, here are my top three new thinkings:

Define the problem. This one cuts across everything we do, yet most underwhelm it. To get there, ask your engineers to define their problems on one page. (Not five, one.) Ask them to use sketches, cartoons, block diagram, arrows, and simple nouns and verbs. When they explain the problem on one page, they understand the problem. When they need two, they don’t.

Test to failure. This one’s subtle but powerful. Test to define product limits, and don’t stop until it breaks. No failure, no learning. To get there, resurrect the venerable test-break-fix cycle and do it until you run out of time (product launch.) Break the old product, test-break-fix the new product until it’s better.

Simplify the product. This is where the money is. Product complexity drives organizational complexity – simplify the product and simply everything. To get there, set a goal for 50% part count reduction, train on Design for Assembly (DFA), and ask engineering for part count data at every design review.

I challenge you to challenge yourself: I challenge you to define new thinking; I challenge you to help them with it; I challenge you to win their hearts and minds.

Stop Doing – it will double your productivity

For the foreseeable future, there will be more work than time. Yet year-on-year we’re asked to get more done and year-on-year we pull it off. Most are already at our maximum hour threshold, so more hours is not the answer. The answer is productivity.

For the foreseeable future, there will be more work than time. Yet year-on-year we’re asked to get more done and year-on-year we pull it off. Most are already at our maximum hour threshold, so more hours is not the answer. The answer is productivity.

Like it or not, there are physical limits to the number of hours worked. At a reasonable upper our bodies need sleep and our families deserve our time. And at the upper upper end, a 25 hour day is not possible. Point is, at some point we draw a line in the sand and head home for the day. Point is, we have finite capacity.

As a thought experiment, pretend you’re at (or slightly beyond) your reasonable upper limit and not going to work more hours. If your work stays the same, your output will be constant and productivity will be zero. But since productivity will increase, your work must change. No magic here, but how to change your work?

Changing your work is about choice – the choice to change your work. You know your work best and you’re the best one to choose. And your choice comes down to what you’ll stop doing.

The easiest thing to stop doing is work you’ve just completed. It’s done, so stop. Finish one, start one is the simplest way to go through life, but it’s not realistic (and productivity does not increase.) Still, it makes for a good mantra: Stop starting and start finishing.

The next things to stop are activities that have no value. Stop surfing and stop playing Angry Birds. Enough said. (If you need professional help to curb your surfing habit, take a look at Leechblock. It helped me.)

The next things to stop are meetings. Here are some guidelines:

- If the meeting is not worth a meeting agenda, don’t go.

- If it’s a status meeting, don’t go – read the minutes.

- If you’re giving status at a status meeting, don’t go – write a short report.

- If there’s a decision to be made, and it affects you, go.

The next thing to stop is email. The best way I know to kick the habit is a self-mandated time limit. Here are some specific suggestions:

- Don’t automatically connect your email to the server – make yourself connect to it.

- Create an email filter for the top ten most important people (You know who they are.) to route them to your Main inbox. Everyone else is routed to a Read Later inbox.

- Check email for fifteen minutes in the morning and fifteen minutes in the afternoon. Start with the Main inbox (important people) and move to the Read Later inbox if you have time. If you don’t have time for the Read Laters, that’s okay – read them later.

- Create an email rule that automatically deletes unread emails in two days and read ones in one.

- Let bad things happen and adjust your email filters and rules accordingly.

Once you’ve chosen to stop the non-productive work, you’ll have more than doubled your productive hours which will double your productivity. That’s huge.

The tough choices come when you must choose between two (or more) sanctioned projects. There are also tricks for that, but that’s different post.

Can’t Say NO

- Yes is easy, no is hard.

- Sometimes slower is faster.

- Yes, and here’s what it will take:

- The best choose what they’ll not do.

- Judge people on what they say no to.

- Work and resources are a matched pair.

- Define the work you’ll do and do just that.

- Adding scope is easy, but taking it out is hard.

- Map yes to a project plan based on work content.

- Challenge yourself to challenge your thinking on no.

- Saying yes to something means saying no to something else.

- The best have chosen wrong before, that’s why they’re the best.

- It’s better to take one bite and swallow than take three and choke.

Have fun at work.

Fun is no longer part of the business equation. Our focus on productivity, quality, and cost has killed it. Killed it dead. Vital few, return on investment, Gantt charts, project plans, and criminal number one – PowerPoint. I can’t stand it.

Fun is no longer part of the business equation. Our focus on productivity, quality, and cost has killed it. Killed it dead. Vital few, return on investment, Gantt charts, project plans, and criminal number one – PowerPoint. I can’t stand it.

What happens when you try to have a little fun at work? People look at you funny. They say: What’s wrong with you? Look! You’re smiling, you must be sick. (I hope you’re not contagious.) Don’t put us at ease, or we may be creative, be innovative, or invent something.

We’ve got it backward. Fun is the best way to improve productivity (and feel good doing it), the best way to improve work quality (excitement and engagement in the work), and the best way to reduce costs (and feel good doing it.) Fun is the best way to make money.

When we have fun we’re happy. When we’re happy we are healthy and engaged. When we’re healthy we come to work (and do a good job.) And when we’re engaged everything is better.

Maybe fun isn’t what’s important. Maybe it’s all the stuff that results from fun. Maybe you should find out for yourself. Maybe you should have some fun and see what happens.

Trust is better than control.

Although it’s more important than ever, trust is in short supply. With everyone doing three jobs, there’s really no time for anything but a trust-based approach. Yet we’re blocked by the fear that trust means loss of control. But that’s backward.

Although it’s more important than ever, trust is in short supply. With everyone doing three jobs, there’s really no time for anything but a trust-based approach. Yet we’re blocked by the fear that trust means loss of control. But that’s backward.

Trust is a funny thing. If you have it, you don’t need it. If you don’t have it, you need it. If you have it, it’s clear what to do – just behave like you should be trusted. If you don’t have it, it’s less clear what to do. But you should do the same thing – behave like you should be trusted. Either way, whether you have it or not, behave like you should be trusted.

Trust is only given after you’ve behaved like you should be trusted. It’s paid in arrears. And people that should be trusted make choices. Whether it’s an approach, a methodology, a technology, or a design, they choose. People that should be trusted make decisions with incomplete data and have a bias for action. They figure out the right thing to do, then do it. Then they present results – in arrears.

I can’t choose – I don’t have permission. To that I say you’ve chosen not to choose. Of course you don’t have permission. Like trust, it’s paid in arrears. You don’t get permission until you demonstrate you don’t need it. If you had permission, the work would not be worth your time. You should do the work you should have permission to do. No permission is the same as no trust. Restating, I can’t choose – I don’t have trust. To that I say you’ve chosen not to choose.

There’s a misperception that minimizing trust minimizes risk. With our control mechanisms we try to design out reliance on trust – standardized templates, standardized process, consensus-based decision making. But it always comes down to trust. In the end, the subject matter experts decide. They decide how to fill out the templates, decided how to follow the process, and decide how consensus decisions are made. The subject matter experts choose the technical approach, the topology, the materials and geometries, and the design details. Maybe not the what, but they certainly choose the how.

Instead of trying to control, it’s more effective to trust up front – to acknowledge and behave like trust is always part of the equation. With trust there is less bureaucracy, less overhead, more productivity, better work, and even magic. With trust there is a personal connection to the work. With trust there is engagement. And with trust there is more control.

But it’s not really control. When subject matter experts are trusted, they seek input from project leaders. They know their input has value so they ask for context and make decisions that fit. Instead of a herd of cats, they’re a swarm of bees. Paradoxically, with a trust-based approach you amplify the good parts of control without the control parts. It’s better than control. It’s where ideas, thoughts and feelings are shared openly and respectfully; it’s where there’s learning through disagreement; it’s where the best business decisions are made; it’s where trust is the foundation. It’s a trust-based approach.

The Bottom-Up Revolution

The No. 1 reason initiatives are successful is support from top management. Whether it’s lean, Six Sigma, Design for Six Sigma or any program, top management support is vital. No argument. It’s easy with full support, but there’s never enough to go around.

The No. 1 reason initiatives are successful is support from top management. Whether it’s lean, Six Sigma, Design for Six Sigma or any program, top management support is vital. No argument. It’s easy with full support, but there’s never enough to go around.

But that’s the way it should be. Top management has a lot going on, much of it we don’t see: legal matters, business relationships, press conferences, the company’s future. If all programs had top management support, they would fail due to resource cannibalization. And we’d have real fodder for our favorite complaint—too many managers.

When there’s insufficient top management support, we have a choice. We can look outside and play the blame game. “This company doesn’t do anything right.” Or we can look inside and choose how we’ll do our work. It’s easy to look outside, then fabricate excuses to do nothing. It’s difficult to look inside, then create the future, especially when we’re drowning in the now. Layer on a new initiative, and frustration is natural. But it’s a choice.

We will always have more work than time….

Organizationally Challenged – Engineering and Manufacturing

Our organizations are set up in silos, and we’re measured that way. (And we wonder why we get local optimization.) At the top of engineering is the VP of the Red Team, who is judged on what it does – product. At the top of manufacturing is the VP of the Blue Team, who is judged on how to make it – process. Red is optimized within Red and same for Blue, sometimes with competing metrics. What we need is Purple behavior.

Here’s a link to a short video (1:14): Organizationally Challenged

And embedded below:

Let me know what you think.

We must broaden “Design”

Design is typically limited to function – what it does – and is done by engineering (red team). Manufacturing is all about how to make it and is done by manufacturing (blue team). Working separately there is local optimization. We must broad to design to include both – red and blue. Working across red-blue boundaries creates magic. This magic can only be done by the purple team.

Below is my first video post. I hope to do more. Let me know what you think.

Time To Think

We live in a strange time where activity equals progress and thinking does not. Thinking is considered inactivity – wasteful, non-productive, worse than sleeping. (At least napping at your desk recharges the battery.) In today’s world there is little tolerance for thinking.

We live in a strange time where activity equals progress and thinking does not. Thinking is considered inactivity – wasteful, non-productive, worse than sleeping. (At least napping at your desk recharges the battery.) In today’s world there is little tolerance for thinking.

For those that think regularly – or have thought once or twice over the last year – we know thinking is important. If we stop and think, everyone thinks thinking is important. It’s just that we’re too busy to stop and think.

It’s difficult to quantify how bad things are – especially if we’re to compare across industries and continents. Sure it’s easy (and demoralizing) to count the hours spent in meetings or the time spent wasting time with email. But they don’t fully capture a company’s intolerance to thinking. We need a tolerance metric and standardized protocol to measure it.

I’ve invented the Thinking Tolerance Metric, TTM, and a way to measure it. Here’s the protocol: On Monday morning – at your regular start time – find a quiet spot and think. (Your quiet spot can be home, work, a coffee shop, or outside.) No smart phone, no wireless, no meetings. Don’t talk to anyone. Start the clock and start thinking. Think all day.

The clock stops when you receive an email from your boss stating that someone complained about your lack of activity. At the end of the first day, turn on your email and look for the complaint. If it’s there, use the time stamp to calculate TTM using Formula 1:

a

TTM = Time stamp of first complaint – regular start time. [1]

a

If TTM is measured in seconds or minutes, that’s bad. If it’s an hour or two, that’s normal.

If there is no complaint for the entire day, repeat the protocol on day two. Go back to your quiet spot and think. At the end of day two, check for the complaint. Repeat until you get one. Calculate TTM using Formula 1.

Once calculated, send me your data by including it in a comment to this post. I will compile the data and publish it in a follow-on post. (Please remember to include your industry and continent.)

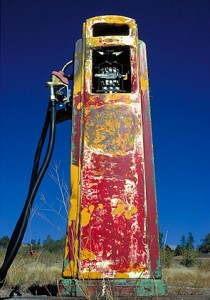

Out Of Gas

You know you’re out of gas when:

You know you’re out of gas when:

- You answer email punctually instead of doing work.

- You trade short term bliss for long term misery.

- You accept an impossible deadline.

- You sit through witless meetings.

- You comply with groupthink.

- You condone bad behavior.

- You placate your boss.

- You write a short post with a bulletized list — because it’s easier.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski