Archive for the ‘Culture’ Category

There is no control. There is only trust.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Control strategies don’t work, but trust strategies do.

Nothing goes as planned. Trying to control things tightly is wasteful. It takes too much energy to batten down all the hatches and keep them that way every-day-all-day. Maybe no water gets in, but the crew doesn’t get enough oxygen and their brains wither.

Trust on the other hand, is flexible and far more efficient. It takes little energy to hire a pro, give them the right task and get out of the way. And with the best pros it requires even less energy because the three-step becomes a two-step – hire them and get out of the way.

When both hands are continuously busy pulling the levers of contingency plans there are no hands left to point toward the future. When both arms are clinging onto the artificial schedule of the project plan there are no arms left to conduct the orchestra. Control strategies make sure even the piccolo plays the right notes at the right time, while trust strategies let the violins adjust based on their ear and intuition and even let the conductors write their own sheet music.

Control is an illusion, but trust is real. The best statistical analyses are rearward-looking and provide no control in a changing environment. (You can’t drive a car by looking in the rear view mirror.) Yet, that’s the state-of-the-art for control strategies – don’t change the inputs, don’t change the process and we’ll get what we got last time. That’s not control. That’s self-limiting.

Trust is real because people and their relationships are real. Trust is a contract between people where one side expects hard work and good judgment and the other side expects to be challenged and to be given the flexibility to do the work as they see fit. Trust-based systems are far more adaptable than if-then control strategies. No control algorithm can effectively handle unanticipated changes in input conditions or unplanned drift in decision criteria, but people and their judgement can. In fact, that’s what people are good at, and they enjoy doing it. And that’s a great recipe for an engaged work force.

Control strategies are popular because they help us believe we have control. And they’re ineffective for the same reason. Trust strategies are not popular because they acknowledge we have no real control and rely on judgment. And that’s why they’re effective.

When control strategies fail, trust strategies are implemented to save the day. When the wheels fall off a project, the best pro in the company is brought in to fix what’s broken. And the best pro is the most trusted pro. And their charge – Tell us what’s wrong (Use your judgement.), tell us how you’re going to fix it (Use your best judgement for that.) and tell us what you need to fix it. (And use your best judgement for that, too.)

In the end, trust trumps control. But only after all other possibilities are exhausted.

Image credit – Dobi.

Hands-On or Hands-Off?

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

Hands-on versus hands-off – as a leader it’s a fundamental choice. And for me the single most important guiding principle is – do what it takes to maintain or strengthen the team’s personal ownership of the work.

If things are going well, keep your hands off. This reinforces the team’s ownership and your trust in them. But it’s not hands-off in and ignore them sense; it’s hands-off in a don’t tell them what to do sense. Walk around, touch base and check in to show interest in the work and avoid interrogation-based methods that undermine your confidence in them. This is not to say a hands-off leader only superficially knows what’s going on, it should only look like the leader has a superficial understanding.

The hands-off approach requires a deep understanding of the work and the people doing it. The hands-off leader must make the time to know the GPS coordinates of the project and then do reconnaissance work to identify the positions of the quagmires and quicksand that lay ahead. The hands-off leader waits patiently just in front of the obstacles and makes no course correction if the team can successfully navigate the gauntlet. But when the team is about to sink to their waists, leader gently nudges so they skirt the dangerous territory.

Unless, of course, the team needs some learning. And in that case, the leader lets the team march it’s project into the mud. If they need just a bit of learning the leader lets them get a little muddy; and if the team needs deep learning, the leader lets them sink to their necks. Either way, the leader is waiting under cover as they approach the impending snafu and is right beside them to pull them out. But to the team, the hands-off leader is not out in front scouting the new territory. To them, the hands-off leader doesn’t pay all that much attention. To the team, it’s just a coincidence the leader happens to attend the project meeting at a pivotal time and they don’t even recognize when the leader subtly plants the idea that lets the team pull themselves out of the mud.

If after three or four near-drowning incidents the team does not learn or change it’s behavior, it’s time for the hands-off approach to look and feel more hands-on. The leader calls a special meeting where the team presents the status of the project and grounds the project in the now. Then, with everyone on the same page the leader facilitates a process where the next bit of work is defined in excruciating detail. What is the next learning objective? What is the test plan? What will be measured? How will it be measured? How will the data be presented? If the tests go as planned, what will you know? What won’t you know? How will you use the knowledge to inform the next experiments? When will we get together to review the test results and your go-forward recommendations?

By intent, this tightening down does not go unnoticed. The next bit of work is well defined and everyone is clear how and when the work will be completed and when the team will report back with the results. The leader reverts back to hands-off until the band gets back together to review the results where it’s back to hands-on. It’s the leader’s judgement on how many rounds of hands-on roulette the team needs, but the fun continues until the team’s behavior changes or the project ends in success.

For me, leadership is always hands-on, but it’s hands-on that looks like hands-off. This way the team gets the right guidance and maintains ownership. And as long as things are going well this is a good way to go. But sometimes the team needs to know you are right there in the trenches with them, and then it’s time for hands-on to look like hands-on. Either way, its vital the team knows they own the project.

There are no schools that teach this. The only way to learn is to jump in with both feet and take an active role in the most important projects.

Image credit – Kerri Lee Smith

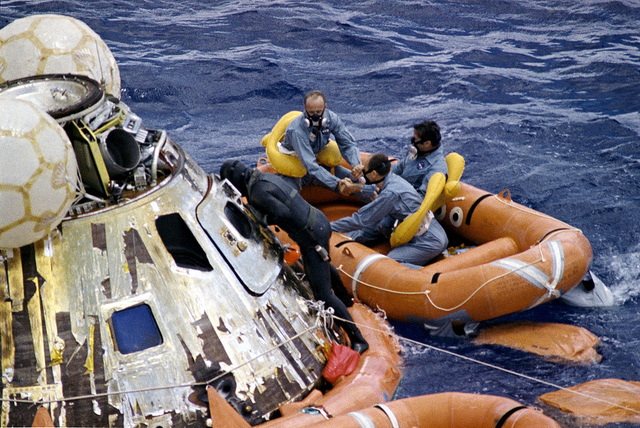

A Life Boat in the Sea of Uncertainty

Work is never perfect, family life is never perfect and neither is the interaction between them. Regardless of your expectations or control strategies, things go as they go. That’s just what they do.

Work is never perfect, family life is never perfect and neither is the interaction between them. Regardless of your expectations or control strategies, things go as they go. That’s just what they do.

We have far less control than we think. In the pure domain of physics the equations govern predictively – perturb the system with a known input in a controlled way and the output is predictable. When the process is followed, the experimental results repeat, and that’s the acid test. From a control standpoint this is as good as it gets. But even this level of control is more limited than it appears.

Physical laws have bounded applicability – change the inputs a little and the equation may not apply in the same way, if at all. Same goes for the environment. What at the surface looks controllable and predictable, may not be. When the inputs change, all bets are off – the experimental results from one test condition may not be predictive in another, even for the simplest systems, In the cold, unemotional world of physical principles, prediction requires judgement, even in lab conditions.

The domains of business and life are nothing like controlled lab conditions. And they’re and not governed by physical laws. These domains are a collection of complex people systems which are governed by emotional laws. Where physics systems delivers predictable outputs for known inputs, people systems do not. Scenario 1. Your group’s best performer is overworked, tired, and hasn’t exercised in four weeks. With no warning you ask them to take on an urgent and important task for the CEO. Scenario 2. Your group’s best performer has a reasonable workload (and even a little discretionary time), is well rested and maintains a regular exercise schedule, and you ask for the same deliverable in the same way. The inputs are the same (the urgent request for the CEO), the outputs are far different.

At the level of the individual – the building block level – people systems are complex and adaptive, The first time you ask a person to do a task, their response is unpredictable. The next day, when you ask them to do a different task, they adapt their response based on yesterday’s request-response interaction, which results in a thicker layer of unpredictability. Like pushing on a bag of water, their response is squishy and it’s difficult to capture the nuance of the interaction. And it’s worse because it takes a while for them to dampen the reactionary waves within them.

One person interacts with another and groups react to other groups. Push on them and there’s really no telling how things will go. One cylo competes with another for shared resources and complexity is further confounded. The culture of a customer smashes against your standard operating procedures and the seismic pressure changes the already unpredictable transfer functions of both companies. And what about the customer that’s also your competitor? And what about the big customer you both share? Can you really predict how things will go? Do you really have control?

What does all this complexity, ambiguity, unpredictability and general lack of control mean when you’re trying to build a culture of accountability? If people are accountable for executing well, that’s fine. But if they’re held accountable for the results of those actions, they will fail and your culture of accountability will turn into a culture of avoiding responsibility and finding another place to work.

People know uncertainty is always part of the equation, and they know it results in unpredictability. And when you demand predictability in a system that’s uncertain by it’s nature, as a leader you lose credibility and trust.

As we swim together in the storm of complexity, trust is the life boat. Trust brings people together and makes it easier to row in the same direction. And after a hard day of mistakenly rowing in the wrong direction, trust helps everyone get back in the boat the next day and pull hard in the new direction you point them.

Image credit – NASA

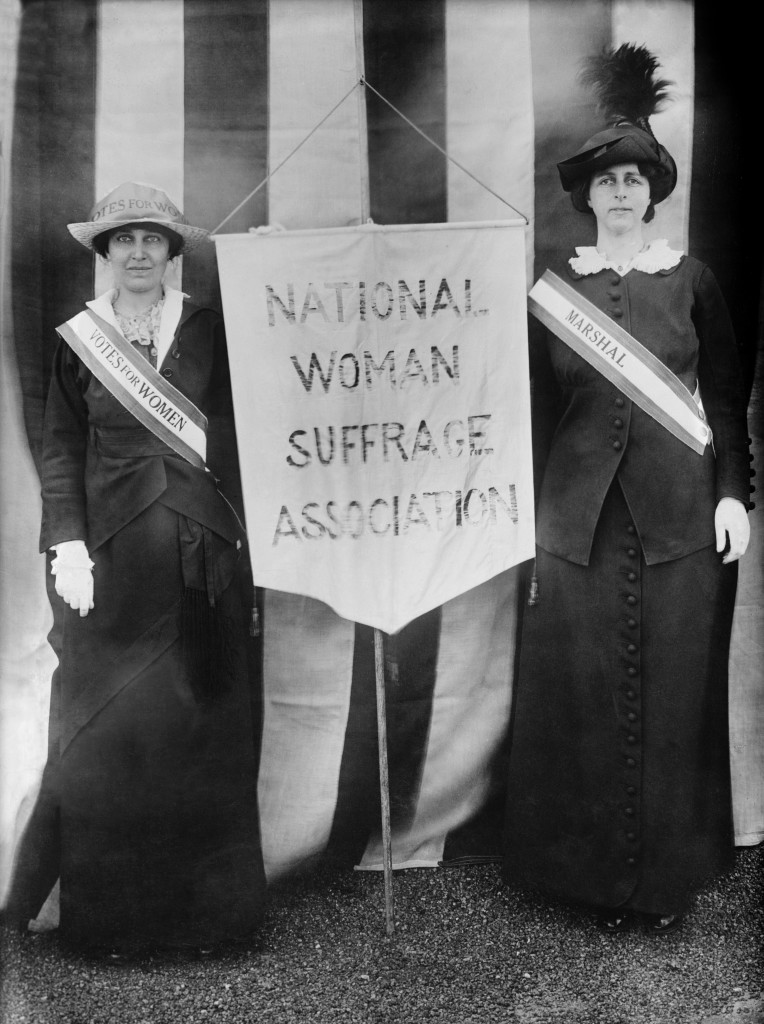

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

If there’s no conflict, there’s no innovation.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

For the successful company, Innovation demands the company does things that are different from what made it successful. Where the company wants to do more of the same (but done better), Innovation calls it as she sees it and dismisses the behavior as continuous improvement. Innovation is a big fan of continuous improvement, but she’s a bit particular about the difference between doing things that are different and things that are the same.

The clashing of perspectives and the gnashing of teeth is not a bad thing, in fact it’s good. If Innovation simply rolls over when doing the same is rationalized as doing differently, nothing changes and the recipe for success runs out of gas. Said another way, company success is displaced by company failure. When innovation creates conflict over sameness she’s doing the company favor. Though it sometimes gives her a bad name, she’s willing to put up with the attack on her character.

The sacred business model is a mortal enemy of Innovation. Those two have been getting after each other for a long time now, and, thankfully, Innovation is willing to stand tall against the sacred business model. Innovation knows even the most sacred business models have a half-life, and she knows that she must actively dismantle them as everyone else in the company tries to keep them on life support long after they should have passed. Innovation creates things that are different (novel), useful and successful to help the company through the sad process of letting the sacred business model die with dignity. She’s willing to do the difficult work of bringing to life a younger more viral business model, knowing full well she’s creating controversy and turmoil at every turn. Innovation knows the company needs help admitting the business model is tired and old, and she’s willing to do the hard work of putting it out to pasture. She knows there’s a lot of misplaced attachment to the tired business model, but for the sake of the company, she’s willing to put it out of its misery.

For a long time now the company’s products have delivered the same old value in the same old way to the same old customers, and Innovation knows this. And because she knows that’s not sustainable, she makes a stink by creating different and more profitable value to different and more valuable customers. She uses different assumptions, different technologies and different value propositions so the company can see the same old value proposition as just that – old (and tired). Yes, she knows she’s kicking company leaders in the shins when she creates more value than they can imagine, but she’s doing it for the right reasons. Knowing full well people will talk about her behind her back, she’s willing to create the conflict needed to discredit old value proposition and adopt a new one.

Innovation is doing the company a favor when she creates strife, and the should company learn to see that strife not as disagreement and conflict for their own sake, rather as her willingness to do what it takes to help the company survive in an unknown future. Innovation has been around a long time, and she knows the ropes. Over the centuries she’s learned that the same old thing always runs out of steam. And she knows technologies and their business models are evolving faster than ever. Thankfully, she’s willing to do the difficult work of creating new technologies to fuel the future, even as the status quo attacks her character.

Without Innovation’s disruptive personality there would be far less conflict and consternation, but there’d also be far less change, far less growth and far less company longevity. Yes, innovation takes a strong hand and is sometimes too dismissive of what has been successful, but her intentions are good. Yes, her delivery is sometimes too harsh, but she’s trying to make a point and trying to help the company survive.

Keep an eye out for the turmoil and conflict that Innovation creates, and when you see it fan the flames. And when hear the calls of distress of middle managers capsized by her wake of disruption, feel good that Innovation is alive and well doing the hard work to keep the company afloat.

The time to worry is not when Innovation is creating conflict and consternation at every turn; the time to worry is when the telltale signs of her powerful work are missing.

The People Business

Things don’t happen on their own, people make them happen.

With all the new communication technologies and collaboration platforms it’s easy to forget that what really matters is people. If people don’t trust each other, even the best collaboration platforms will fall flat, and if they don’t respect each other, they won’t communicate – even with the best technology.

Companies put stock in best practices like they’re the most important things, but they’re not. Because of this unnatural love affair, we’re blinded to the fact people are what make best practices best. People create them, people run them, and people improve them. Without people there can be no best practices, but on the flip-side, people can get along just fine without best practices. (That says something, doesn’t it?) Best practices are fine when processes are transactional, but few processes are 100% transactional to the core, and the most important processes are judgement-based. In a foot race between best practices and good judgement, I’ll take people and their judgment – every day.

Without a forcing function, there can be no progress, and people are the forcing function. To be clear, people aren’t the object of the forcing function, they are the forcing function. When people decide to commit to a cause, the cause becomes a reality. The new reality is a result – a result of people choosing for themselves to invest their emotional energy. People cannot be forced to apply their life force, they must choose for themselves. Even with today’s “accountable to outcomes” culture, the power of personal choice is still carries the day, though sometimes it’s forced underground. When pushed too hard, under the cover of best practice, people choose to work the rule until the clouds of accountability blow over.

When there’s something new to do, processes don’t do it – people do. When it’s time for some magical innovation, best practices don’t save the day – people do. Set the conditions for people to step up and they will; set the conditions for them to make a difference and they will. Use best practices if you must, but hold onto the fact that whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Image credit – Vicki & Chuck Rogers

Innovation is alive and well.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself; rather, it’s a result of something. Set the right input conditions, monitor the right things in the right ways, and innovation weaves itself into the genetic makeup of your company. Like ivy, it grabs onto outcroppings that are the heretics and wedges itself into the cracks of the organization. It grows unpredictably, it grows unevenly, it grows slowly. And one day you wake up and your building is covered with the stuff.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself; rather, it’s a result of something. Set the right input conditions, monitor the right things in the right ways, and innovation weaves itself into the genetic makeup of your company. Like ivy, it grabs onto outcroppings that are the heretics and wedges itself into the cracks of the organization. It grows unpredictably, it grows unevenly, it grows slowly. And one day you wake up and your building is covered with the stuff.

Ivy doesn’t grow by mistake – It takes some initial plantings in strategic locations, some water, some sun, something to attach to, a green thumb and patience. Innovation is the same way.

There’s no way to predict how ivy will grow. One young plant may dominate the others; one trunk may have more spurs and spread broadly; some tangles will twist on each other and spiral off in unforeseen directions; some vines will go nowhere. Though you don’t know exactly how it will turn out, you know it will be beautiful when the ivy works its evolutionary magic. And it’s the same with innovation.

Ivy and innovation are more similar than it seems, and here are some rules that work for both:

- If you don’t plant anything, nothing grows.

- If growing conditions aren’t right, nothing good comes of it.

- Without worthy scaffolding, it will be slow going.

- The best time to plant the seeds was three years ago.

- The second best time to plant is today.

- If you expect predictability and certainty, you’ll be frustrated.

Innovation is the output of a set of biological systems – our people systems – and that’s why it’s helpful to think of innovation as if it’s alive because, well, it is. And like with a thriving colony of ants that grows steadily year-on-year, these living systems work well. From 10,000 foot perspective ants and innovation look the same – lots of chaotic scurrying, carrying and digging. And from an ant-to-ant, innovator-to-innovator perspective they are the same – individuals working as a coordinated collective within a shared mindset of long term sustainability.

Image credit – Cindy Cornett Seigle

Compete with No One

Today’s commercial environment is fierce. All companies have aggressive growth objectives that must be achieved at all costs. But there’s a problem – within any industry, when the growth goals are summed across competitors, there are simply too few customers to support everyone’s growth goals. Said another way, there are too many competitors trying to eat the same pie. In most industries it’s fierce hand-to-hand combat for single-point market share gains, and it’s a zero sum game – my gain comes at your loss. Companies surge against each other and bloody skirmishes break out over small slivers of the same pie.

Today’s commercial environment is fierce. All companies have aggressive growth objectives that must be achieved at all costs. But there’s a problem – within any industry, when the growth goals are summed across competitors, there are simply too few customers to support everyone’s growth goals. Said another way, there are too many competitors trying to eat the same pie. In most industries it’s fierce hand-to-hand combat for single-point market share gains, and it’s a zero sum game – my gain comes at your loss. Companies surge against each other and bloody skirmishes break out over small slivers of the same pie.

The apex of this glorious battle is reached when companies no longer have points of differentiation and resort to competing on price. This is akin to attrition warfare where heavy casualties are taken on both sides until the loser closes its doors and the winner emerges victorious and emaciated. This race to the bottom can only end one way – badly for everyone.

Trench warfare is no way for a company to succeed, and it’s time for a better way. Instead of competing head-to-head, it’s time to compete with no one.

To start, define the operating envelope (range of inputs and outputs) for all the products in the market of interest. Once defined, this operating envelope is off limits and the new product must operate outside the established design space. By definition, because the new product will operate with input conditions that no one else’s can and generate outputs no one else can, the product will compete with no one.

In a no-to-yes way, where everyone’s product says no, yours is reinvented to say yes. You sell to customers no one else can; you sell into applications no one else can; you sell functions no one else can. And in a wicked googly way, you say no to functions that no one else would dare. You define the boundary and operate outside it like no one else can.

Competing against no one is a great place to be – it’s as good as trench warfare is bad – but no one goes there. It’s straightforward to define the operating windows of products, and, once define it’s straightforward to get the engineers to design outside the window. The hard part is the market/customer part. For products that operate outside the conventional window, the sales figures are the lowest they can be (zero) and there are just as many customers (none). This generates extreme stress within the organization. The knee-jerk reaction is to assign the wrong root cause to the non-existent sales. The mistake – “No one sells products like that today, so there’s no market there.” The truth – “No one sells products like that today because no one on the planet makes a product like that today.”

Once that Gordian knot is unwound, it’s time for the marketing community to put their careers on the line. It’s time to push the organization toward the scary abyss of what could be very large new market, a market where the only competition would be no one. And this is the real hard part – balancing the risk of a non-existent market with the reward of a whole new market which you’d call your own.

If slugging it out with tenacious competitors is getting old, maybe it’s time to compete with no one. It’s a different battle with different rules. With the old slug-it-out war of attrition, there’s certainty in how things will go – it’s certain the herd will be thinned and it’s certain there’ll be heavy casualties on all fronts. With new compete-with-no-one there’s uncertainty at every turn, and excitement. It’s a conflict governed by flexibility, adaptability, maneuverability and rapid learning. Small teams work in a loosely coordinated way to test and probe through customer-technology learning loops using rough prototypes and good judgement.

It’s not practical to stop altogether with the traditional market share campaign – it pays the bills – but it is practical to make small bets on smart people who believe new markets are out there. If you’re lucky enough to have folks willing to put their careers on the line, competing with no one is a great way to create new markets and secure growth for future generations.

Image credit – mae noelle

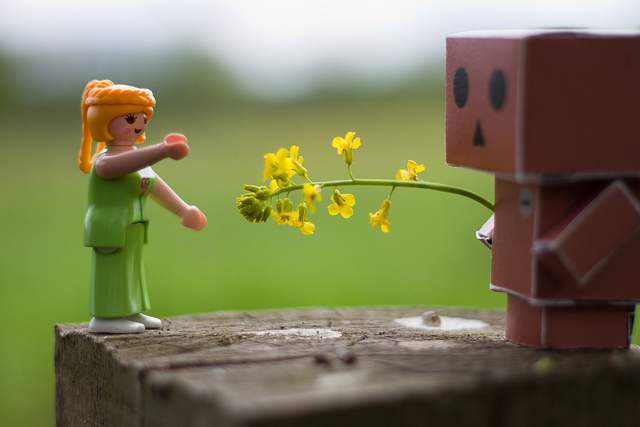

The Lonely Chief Innovation Officer

Chief Innovation Officer is a glorious title, and seems like the best job imaginable. Just imagine – every-day-all-day it’s: think good thoughts, imagine the future, and bring new things to life. Sounds wonderful, but more than anything, it’s a lonely slog.

Chief Innovation Officer is a glorious title, and seems like the best job imaginable. Just imagine – every-day-all-day it’s: think good thoughts, imagine the future, and bring new things to life. Sounds wonderful, but more than anything, it’s a lonely slog.

In theory it’s a great idea – help the company realize (and acknowledge) what it’s doing wrong (and has been for a long time now), take resources from powerful business units and move them to a fledgling business units that don’t yet sell anything, and do it without creating conflict. Sounds fun, doesn’t it?

Though there are several common problems with the role of Chief Innovation Officer (CIO), the most significant structural issue, by far, is the CIO has no direct control over how resources are allocated. Innovation creates products, services and business models that are novel, useful and successful. That means innovation starts with ideas and ends with commercialized products and services. And no getting around it, this work requires resources. The CIO is charged with making innovation come to be, yet authority to allocate resources is withheld. If you’re thinking about hiring a Chief Innovation Officer, here’s a rule to live by:

If resources are not moved to projects that generate novel ideas, convert those ideas into crazy prototypes and then into magical products that sell like hotcakes, even the best Chief Innovation Officer will be fired within two years.

Structurally, I think it’s best if the powerful business units (who control the resources) are charged with innovation and the CIO is charged with helping them. The CIO helps the business units create a forward-looking mindset, helps bring new thinking into the old equation, and provides subject matter expertise from outside the company. While this addresses the main structural issue, it does not address the loneliness.

The CIO’s view of what worked is diametrically opposed to those that made it happen. Where the business units want to do more of what worked, the CIO wants to dismantle the engine of success. Where the engineers that designed the last product want to do wring out more goodness out of the aging hulk that is your best product, the CIO wants to obsolete it. Where the business units see the tried-and-true business model as the recipe for success, the CIO sees it as a tired old cowpath leading to the same old dried up watering hole. If this sounds lonely, it’s because it is.

To combat this fundamental loneliness, the CIO needs to become part of a small group of trusted CIOs from non-competing companies. (NDAs required, of course.) The group provides its members much needed perspective, understanding and support. At the first meeting the CIO is comforted by the fact that loneliness is just part of the equation and, going forward, no longer takes it personally. Here are some example deliverables for the group.

Identify the person who can allocate resources and put together a plan to help that person have a big problem (no incentive compensation?) if results from the innovation work are not realized.

Make a list of the active, staffed technology projects and categorize them as: improving what already exists, no-to-yes (make a product/service do something it cannot), or yes-to-no (eliminate functionality to radically reduce the cost signature and create new markets).

For the active, staffed projects, define the market-customer-partner assumptions (market segment, sales volume, price, cost, distribution and sales models) and create a plan to validate (or invalidate) them.

To the person with the resources and the problem if the innovation work fizzles, present the portfolio of the active, staffed projects and its validated roll-up of net profit, and ask if portfolio meets the growth objectives for the company. If yes, help the business execute the projects and launch the products/services. If no, put a plan together to run Innovation Burst Events (IBEs) to come up with more creative ideas that will close the gap.

The burning question is – How to go about creating a CIO group from scratch? For that, you need to find the right impresario that can pull together a seemingly disparate group of highly talented CIOs, help them forge a trusting relationship and bring them the new thinking they need.

Finding someone like that may be the toughest thing of all.

Image credit – Giant Humanitarian Robot.

Innovation is a Choice

A body in motion tends to stay in motion, unless it’s perturbed by an external force. And, it’s the same with people – we keep doing what we’re doing until there’s a reason we cannot. If it worked, there’s no external force to create changes, so we do more of what worked. If it didn’t work, while that should result in an external force strong enough to create change, often it doesn’t and we try more of what didn’t work, but try it harder. Though the scenarios are different, in both the external force is insufficient to create new behavior.

A body in motion tends to stay in motion, unless it’s perturbed by an external force. And, it’s the same with people – we keep doing what we’re doing until there’s a reason we cannot. If it worked, there’s no external force to create changes, so we do more of what worked. If it didn’t work, while that should result in an external force strong enough to create change, often it doesn’t and we try more of what didn’t work, but try it harder. Though the scenarios are different, in both the external force is insufficient to create new behavior.

In order to know which camp you’re in, it’s important to know how we decide between what worked and what didn’t (or between working and not working). To decide, we compare outcomes to expectations, and if outcomes are more favorable than our expectations, it worked; if less favorable, it didn’t. It’s strange, but true – what we expect delineates what worked from what didn’t and what’s good enough from what isn’t. In that way, it’s our choice.

Whether our business model is working, isn’t working, or hasn’t worked, what we think and do about it is our choice. What that means is, regardless of the magnitude of the external force, we decide if it’s large enough to do our work differently or do different work. And because innovation starts with different, what that means is innovation is a choice – our choice.

Really, though, external forces don’t create new behavior, internal forces do. We watch the culture around us and sense the external forces it creates on us, then we look inside and choose to apply the real force behind innovation – our intrinsic motivation. If we’re motivated by holding on to what we have, we’ll spend little of our life force on innovation. If we’re motivated by a healthy dissatisfaction with the status quo, we’ll empty our tank in the name of innovation.

Who is tasked with innovation at your company is an important choice, because while the tools and methods of innovation can be taught, a person’s intrinsic motivation, a fundamental forcing function of innovation, cannot.

Image credit – Ed Yourdon

To improve innovation, improve clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

For clarity on the innovative new product, here’s what the CEO needs.

Valuable Customer Outcomes – how the new product will be used. This is done with a one page, hand sketched document that shows the user using the new product in the new way. The tool of choice is a fat black permanent marker on an 81/2 x 11 sheet of paper in landscape orientation. The fat marker prohibits all but essential details and promotes clarity. The new features/functions/finish are sketched with a fat red marker. If it’s red, it’s new; and if you can’t sketch it, you don’t have it. That’s clarity.

The new value proposition – how the product will be sold. The marketing leader creates a one page sales sheet. If it can’t be sold with one page, there’s nothing worth selling. And if it can’t be drawn, there’s nothing there.

Customer classification – who will buy and use the new product. Using a two column table on a single page, these are their attributes to define: Where the customer calls home; their ability to pay; minimum performance threshold; infrastructure gaps; literacy/capability; sustainability concerns; regulatory concerns; culture/tastes.

Market classification – how will it fit in the market. Using a four column table on a single page, define: At Whose Expense (AWE) your success will come; why they’ll be angry; what the customer will throw way, recycle or replace; market classification – market share, grow the market, disrupt a market, create a new market.

For clarity on the creative work, here’s what the CEO needs: For each novel concept generated by the Innovation Burst Event (IBE), a single PowerPoint slide with a picture of its thinking prototype and a word description (limited to 12 words).

For clarity on the problems to be solved the CEO needs a one page, image-based definition of the problem, where the problem is shown to occur between only two elements, where the problem’s spacial location is defined, along with when the problem occurs.

For clarity on the viability of the new technology, the CEO needs to see performance data for the functional prototypes, with each performance parameter expressed as a bar graph on a single page along with a hyperlink to the robustness surrogate (test rig), test protocol, and images of the tested hardware.

For clarity on commercialization, the CEO should see the project in three phases – a front, a middle, and end. The front is defined by a one page project timeline, one page sales sheet, and one page sales goals. The middle is defined by performance data (bar graphs) for the alpha units which are hyperlinked to test protocols and tested hardware. For the end it’s the same as the middle, except for beta units, and includes process capability data and capacity readiness.

It’s not easy to put things on one page, but when it’s done well clarity skyrockets. And with improved clarity the right concepts are created, the right problems are solved, the right data is generated, and the right new product is launched.

And when clarity extends all the way to the CEO, resources are aligned, organizational confusion dissipates, and all elements of innovation work happen more smoothly.

Image credit – Kristina Alexanderson

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski