Archive for the ‘Clarity’ Category

How To Create The Conditions For Good Things To Happen

Reduce the energy cost of virtue so it’s less than the energy cost of sin. (Dave Snowden)

Reduce the energy cost of virtue so it’s less than the energy cost of sin. (Dave Snowden)

Said another way – make it easy to do the right thing.

Don’t push through. Move obstacles out of the way.

Don’t tell people about their problem. Ask people about their problem.

Try small experiments and do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

Don’t tell people they have a problem. Volunteer to help them.

Instead of Ready, Fire, Aim, try Ready, Aim, Fire.

Before trying to improve things, define the system as it is.

When two competing theories cause disagreement, agree to try both.

Slow down to go faster.

Say no so you can say yes.

Give praise in public and give criticism in private.

Say nothing negative unless you’ve exhausted all other possibilities.

Build trust BEFORE you need it.

These are good ways to create the conditions for good things to happen.

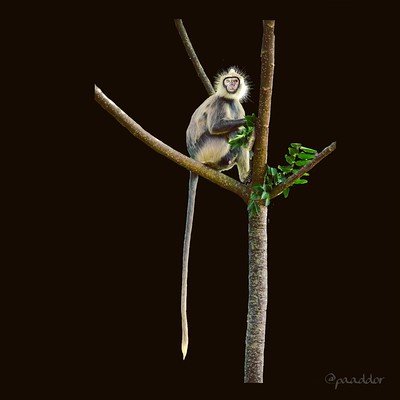

Image credit — Peter Addor – The monkey that makes a monkey of us.

It’s All About Your Questions

When you know the answer, do you ask the question to test others?

When you know the answer, do you ask the question to test others?

When you know the answer, do you ask the question to help others think differently?

When you know the answer, do you keep quiet because it’s not the right time for a question?

When you know the answer, do you ask the question even though it’s not the right time for a question?

What does that say about you?

When you think you know the answer, do you ask the question to seek the right answer?

When you think you know the answer, do you ask the question and risk looking like you don’t know?

When you think you know the answer, do you keep quiet for reasons you don’t understand?

What does that say about you?

When you don’t know the answer, do you ask in public to solicit diverse perspectives?

When you don’t know the answer, do you ask someone you trust in private?

When you don’t know the answer, do you throw away the question?

What does that say about you?

When you’re asked a question that doesn’t need to be answered yet, do you ask, “Do we need to know that yet?”

When you’re asked a question that cannot be answered yet, do you ask, “Can we know that yet?”

When you’re asked a question that is too costly to answer, do you ask, “Do we have enough time and money to know that?”

Do you have the courage to ask those three questions?

What does that say about you?

Image credit – Tambako The Jaguar

Things aren’t good or bad. We make them that way.

More isn’t better, it’s just more. What makes it better is how it compares to the expectations we set.

More isn’t better, it’s just more. What makes it better is how it compares to the expectations we set.

Less isn’t worse, it’s just less. What makes it work is how we compare it to what we want.

Enough isn’t enough until we decide it is.

We forget what we have until we don’t have it.

Our health isn’t bad until we can’t do what we want to do. But don’t we decide what we want to do?

Activities aren’t fun unless the experiences exceed our minimum level of enjoyment. But aren’t we the ones who define that threshold?

When we look back at last year, we will have more of some things and less of others. None of the situations are good or bad, but we will make them that way by comparing what happened with what we wanted, what we expected, or the thresholds society sets for us. We will decide what’s good and what’s bad. We will define our level of happiness.

When we look forward to next year, we will set expectations or goals to have more of some things and less of others. We will define those thresholds and establish the criteria for good/bad. And at the end of the year, we will compare what happened against our self-defined thresholds. We will be responsible for our happiness.

Things happened last year. They were not good or bad. They just were. We can’t change what happened, but we can change how we feel about what happened. At the end of the year, may we be aware that we set our good/bad thresholds for the year. And may we remember that we defined our thresholds somewhat arbitrarily, and we can reset them along the way.

Things will happen next year. They will not be good or bad. They will just be. We won’t have infinite control over what happens, but we can control our good/bad thresholds. At the start of next year, may we set our good/bad thresholds skillfully.

Image credit — Ajay Goel

Elevate the Holiday Season by Understanding WHY

What is this all about?

What is this all about?

What is the reason you do what you do? What’s your WHY behind the WHAT?

When you don’t do what you said you’d do, what’s the reason? And what does that say about you?

If the reason is right, I think it can be okay NOT to do something you said you’d do. But I try to set a high bar on this one.

When things get tough, what gets you to push through? For me, it’s about doing something for the people I care about.

When things go well, what causes you to give credit to others? For me, it’s about building momentum and helping people understand the special things they did to make it happen.

Why do you show up? When you ask yourself, do you have an answer?

How do you show up for? And the more difficult question – WHY?

When is it okay to be compliant in a minimum energy way? And how do you decide that’s okay?

When do you decide to apply your whole self to something that others think is misaligned with the charter? I think this says a lot about a person.

What are you willing to do even though you know you’ll be judged negatively for doing it? I’m often unsure why to do it, but I’m sure it’s the right thing to do. I don’t know what that says about me, but I’m okay with it.

To me, the WHY is far more important than the WHAT. The WHY explains things. The WHY tells the story. The WHY gives guidance on what will happen next time.

When you do something happen that’s out of the ordinary (a WHAT), I suggest you try to figure out the WHY. I have found that some seemingly nonsensical WHATs make a lot of sense when you understand the WHY underpinning the WHAT.

And during this holiday season, may you give people the benefit of the doubt on their WHATs, and take the time to understand their highly personal WHYs. That can make for a happier holiday season for all.

Image credit — Christopher Henry

Staying Too Long vs. Leaving Too Soon

When you start something, by definition, you will end it.

When you start something, by definition, you will end it.

All good things come to an end. So do all bad things. That’s how it goes with things.

All new things start with the end of old things. That’s how things are.

What does it say when a phase of your life comes to an end?

Doesn’t the start of a new phase demand the end of an existing one?

When something ends, do you curse it or celebrate it, do both, or neither? And how do you decide?

If you stay with the old thing too long, what does that say? And how do you know it was too long?

Can you know it will be too long before you stay too long?

If you leave too soon, can you know that before you leave?

The follow-on results of a decision do not determine the quality of a decision.

There is no right decision to make.

Make the decision and then make it right.

Image credit — Karissa Burnett

When is a rule not a rule?

What’s the rule? Are you sure?

What’s the rule? Are you sure?

Where did the rule come from? And how do you know?

When the rule was created, was there also a rule that it could not be changed?

Show me the rule book!

Is the rule always applicable, even after hours?

If the rule is limited to a certain location, work from home.

Is it a rule or a ritual? It’s easier to abstain from rituals.

Is it a rule or a rut? Ruts aren’t rules; they’re just how we’ve done it.

Is it a rule or a guideline? Squinting can easily transform a rule into a guideline.

If there’s a disagreement about what the rule is, take a position that’s advantageous to you.

If you don’t know it’s a rule, there’s no need to break it.

If one knows who broke the rule, was it really broken?

If the rules are unknown, don’t follow them.

If the context changed around the rule, the rule is no longer applicable.

If no one remembers why the rule exists, it’s no longer a rule.

If you don’t like a rule, run an experiment to show its shortcomings.

If a rule blocks progress, make progress.

If no one knows a rule was broken, it wasn’t broken.

Image credit — nirak68

Sixteen Years of Wednesdays

I’ve written a blog post every Wednesday for the last sixteen years.

I’ve written a blog post every Wednesday for the last sixteen years.

The first years were difficult because I was unsure if my writing was worth reading. Writing became easier when I realized it wasn’t about what others thought of my writing. For the next ten years, I let go and wrote about things I wanted to write about. I transitioned from describing things to others to writing to understand things for myself. I learned that writing about a topic helped me understand it better.

By writing every week, my writing skills improved. I learned to eliminate words and write densely. Early on, I wanted to sound smart and, over time, I became comfortable using plain language and everyday words. My improved writing skills have helped my career.

Over the last several years, writing has become difficult for me. After 800 blog posts, it became difficult to come up with new topics, and I started putting pressure on myself by trying to live up to an imaginary standard. I blocked my own flow, everything tightened, and the words came reluctantly.

Then I became tired of paragraphs. I wrote in topic sentences, bulletized lists, and a sequence of questions. Each topic sentence could have been the topic of a blog post; the individual bullets were standalone thoughts; and the questions ganged up to build the skeleton of a big theme. For some reason, it was easier to come up with a collection of big thoughts than to write in detail about a single topic.

I’m not sure what the future will bring, but thanks for reading,

Mike

Image credit — chuddlesworth

Skillful Awareness

When do you bring your whole self to the endeavor? You can’t do this every time, and that’s okay.

When do you bring your whole self to the endeavor? You can’t do this every time, and that’s okay.

What are the conditions that cause you to engage fully? Full engagement is expensive. Spend wisely.

What about the situation causes you to run toward the problem? Solve the right ones, but leave some for the rest of us.

Which situations bring out the best in you? Sometimes your best isn’t very good, and that’s okay.

When do you block yourself from jumping into the adventure? All adventures aren’t worth the jump. Block wisely.

What are the conditions that cause you to phone it in? Sometimes the best choice is a phone call.

What about the situation causes you to give others a chance to run toward the problem? There’s nothing wrong with that. Save yourself for the right problems.

Which situations demand that you protect your best self? It’s okay to protect yourself and live to fight another day. That’s why they make bulletproof vests.

Sometimes we get caught up in the heat of battle and bring our energy in an unskillful way. And sometimes we are lulled into inaction when bringing our energy is the more skillful action.

I have found that maintaining awareness helps me allocate my energy wisely and skillfully.

May you be aware of your surroundings and your self.

Image credit – Jan Mosimann

Some Questions For You

Are you working on important problems?

Are you working on important problems?

Or are you seeking out important problems?

Or are you connecting with people who work on important problems?

I ask because I think working on important problems is important.

Are you working with people who build you up?

Do you separate from those who do the opposite?

Are you building up others?

Do you call out those who do the opposite?

Are you seeking out people who deserve rebuilding?

Do you suppress the unbuilding that creates the need for rebuilding?

I ask because I think building builds character.

Does your work matter?

What do you do when it doesn’t?

To whom does your work matter?

What do you do if you don’t know?

Do you seek out work that matters?

What do you do to block yourself from seeking out work that matters?

How do you decide if your work matters?

What do you do when you are unsure?

I ask because I think it matters.

Who is important to you?

How can you spend more time with them?

Who is not important to you?

How can you spend less time with them?

I ask because I think that’s important.

What do you think is most important?

What deserves more attention?

Who deserves to know?

When will you tell them?

I ask because I think this adds meaning to our lives.

Degrees of Not Knowing

You know you know, but you don’t.

You know you know, but you don’t.

You think you know, but you don’t.

You’re pretty sure you don’t know.

You know you don’t know, you think it’s not a problem that you don’t, but it is a problem.

You know you don’t know, you think it’s a problem that you don’t, but it isn’t a problem.

You don’t know, you don’t know that you don’t need to know yet, and you try.

You don’t know, you know you don’t need to know yet, and you wait.

You don’t know, you can’t know, you don’t know you can’t, and you try.

You don’t know, you can’t know, you know you can’t, and you wait.

Some skills you may want to develop….

To know when you know and when you don’t, ask yourself if you know and listen to the response.

To know if it’s a problem that you don’t know or if it isn’t, ask yourself, “Is it a problem that I don’t know?” If it isn’t, let it go. If it is, get after it.

To know if it’s not time to know or if it is, ask yourself, “Do I have to know this right now?” If it’s not time, wait. If it is time, let the learning begin. Trying to know before you need to is a big waste of time.

To know if you can’t know or if you can, ask yourself, “Can I know this?” and listen for the answer. Trying to learn when you can’t is the biggest waste of time.

Image credit — Dennis Skley

Write to think or think to write?

I started writing because I had no mentor to help me. I thought I could help myself grow. I thought I could write to better understand my ideas. I thought I could use writing to mentor myself. I tried it. It was difficult. It was scary. But I started.

I started writing because I had no mentor to help me. I thought I could help myself grow. I thought I could write to better understand my ideas. I thought I could use writing to mentor myself. I tried it. It was difficult. It was scary. But I started.

You will see the title, but you won’t see my scrap paper scribblings that emerge as I struggle to converge on a topic. Prismatic shapes, zig-zags, arrows pointing toward nothing, nested triangles, cross-hatched circles, words that don’t go together, random words. And when a topic finds me, I move to the laptop, but you won’t see that either.

You will see the sentences and paragraphs that hang together. You won’t see the clustered fragments of almost sentences, the disjointed paragraphs, the out-of-sequence logic, the inconsistency of tense, and the wrong words. You won’t see my head pressed to the kitchen table as I struggle to unshuffle the deck.

You will see the density of my writing. You won’t see the preening.

You will see a curated image and a shout out to the owner. You won’t see me spend 30 minutes searching for an image that supports the blog post obliquely.

You will see the research underpinning the main points, but you won’t see me doing it. Books on and off the shelf, books on the floor, technical papers in my backpack, old presentations in forgotten folders, YouTube, blogs, and podcasts. Far too many podcasts.

You will see this week’s blog post on Wednesday night, Thursday morning, or Thursday afternoon, depending on your time zone. You won’t see the 750+ blog posts from 15 years of Wednesdays.

When it was time to send out my first blog post, I was afraid. I questioned whether the content was worthy, whether I was right, and whether it made sense. I struggled to push the button. I hesitated, hesitated again, and pushed the button. And nothing bad happened.

When it was time to send out this blog post, I was confident the content was worthy, confident I was right, and confident that it made sense. I put myself out there, and when it was time to hit the button, I did not hesitate because I wrote it for me.

Image credit — Charlie Marshall

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski