Posts Tagged ‘Success’

Always Tight on Time

There always far more tasks than there is time. Same for vacations and laundry. And that’s why it’s important to learn when-and how-to say no. No isn’t a cop-out. No is ownership of the reality we can’t do everything. The opposite of no isn’t maybe; the opposite of no is yes while knowing full well it won’t get done. Where the no-in-the-now is skillful, the slow no is unskillful.

There always far more tasks than there is time. Same for vacations and laundry. And that’s why it’s important to learn when-and how-to say no. No isn’t a cop-out. No is ownership of the reality we can’t do everything. The opposite of no isn’t maybe; the opposite of no is yes while knowing full well it won’t get done. Where the no-in-the-now is skillful, the slow no is unskillful.

When you know the work won’t get done and when you know the trip to the Grand Canyon won’t happen, say no. Where yes is the instigator of dilution, no is the keystone of effectiveness.

And once it’s yes, Parkinson’s law kicks you in the shins. It’s not Parkinson’s good idea or Parkinson’s conjecture – it’s Parkinson’s law. And it’s a law is because the work does, in fact, always fill the time available for its completion. If the work fills the time available, it makes sense to me to define the time you’ll spend on a task before starting the task. More important tasks are allocated more time, less important tasks get less and the least important get a no-in-the-now. To beat Parkinson at his own game, use a timer.

Decide how much time you want to spend on a task. Then, to improve efficiency, divide by two. Set a countdown timer (I like E.gg Timer) and display it in the upper right corner of your computer screen. (As I write this post, my timer has 1:29 remaining.) As the timer counts down you’ll converge on completeness.

80% right, 100% done is a good mantra.

I guess I’m done now.

Image credit — bruno kvot

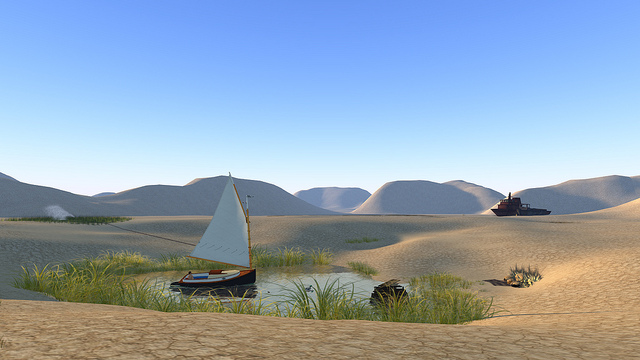

Channel your inner sea captain.

When it’s time for new work, the best and smartest get in a small room to figure out what to do. The process is pretty simple: define a new destination, and, to know when they journey is over, define what it looks like to live there. Define the idealized future state and define the work to get there. Turn on the GPS, enter the destination and follow the instructions of the computerized voice.

When it’s time for new work, the best and smartest get in a small room to figure out what to do. The process is pretty simple: define a new destination, and, to know when they journey is over, define what it looks like to live there. Define the idealized future state and define the work to get there. Turn on the GPS, enter the destination and follow the instructions of the computerized voice.

But with new work, the GPS analogy is less than helpful. Because the work is new, there’s no telling exactly where the destination is, or whether it exists at all. No one has sold a product like the one described in the idealized future state. At this stage, the product definition is wrong. So, set your course heading for South America though the destination may turn out to be Europe. No matter, it’s time to make progress, so get in the car and stomp the accelerator.

But with new work there is no map. It’s never been done before. Though unskillful, the first approach is to use the old map for the new territory. That’s like using map data from 1928 in your GPS. The computer voice will tell you to take a right, but that cart path no longer exists. The GPS calls out instructions that don’t match the street signs and highway numbers you see through the windshield. When the GPS disagrees with what you see with your eyeballs, the map is wrong. It’s time to toss the GPS and believe the territory.

With new work, it’s not the destination that’s important, the current location is most important. The old sea captains knew this. Site the stars, mark the time, and set a course heading. Sail for all your worth until the starts return and as soon as possible re-locate the ship, set a new heading and repeat. The course heading depends more on location than destination. If the ship is east of the West Indies, it’s best to sail west, and if the ship is to the north, it’s best to sail south. Same destination, different course heading.

When the work is new, through away the old maps and the GPS and channel your inner sea caption. Position yourself with the stars, site the landmarks with your telescope, feel the wind in your face and use your best judgement to set the course heading. And as soon as you can, repeat.

Image credit – Timo Gufler.

If you don’t know the critical path, you don’t know very much.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Two words to live by: Critical Path.

By definition, the next task to work on is the next task on the critical path. How do you tell if the task is on the critical path? When you are late by one day on a critical path task, the project, as a whole, will finish a day late. If you are late by one day and the project won’t be delayed, the task is not on the critical path and you shouldn’t work on it.

Rule 1: If you can’t work the critical path, don’t work on anything.

Working on a non-critical path task is worse than working on nothing. Working on a non-critical path task is like waiting with perspiration. It’s worse than activity without progress. Resources are consumed on unnecessary tasks and the resulting work creates extra constraints on future work, all in the name of leveraging the work you shouldn’t have done in the first place.

How to spot the critical path? If a similar project has been done before, ask the project manager what the critical path was for that project. Then listen, because that’s the critical path. If your project is similar to a previous project except with some incremental newness, the newness is on the critical path.

Rule 2: Newness, by definition, is on the critical path.

But as the level of newness increases, it’s more difficult for project managers to tell the critical path from work that should wait. If you’re the right project manager, even for projects with significant newness, you are able to feel the critical path in your chest. When you’re the right project manager, you can walk through the cubicles and your body is drawn to the critical path like a divining rod. When you’re the right project manager and someone in another building is late on their critical path task, you somehow unknowingly end up getting a haircut at the same time and offering them the resources they need to get back on track. When you’re the right project manager, the universe notifies you when the critical path has gone critical.

Rule 3: The only way to be the right project manager is to run a lot of projects and read a lot. (I prefer historical fiction and biographies.)

Not all newness is created equal. If the project won’t launch unless the newness is wrestled to the ground, that’s level 5 newness. Stop everything, clear the decks, and get after it until it succumbs to your diligence. If the product won’t sell without the newness, that’s level 5 and you should behave accordingly. If the newness causes the product to cost a bit more than expected, but the project will still sell like nobody’s business, that’s level 2. Launch it and cost reduce it later. If no one will notice if the newness doesn’t make it into the product, that’s level 0 newness. (Actually, it’s not newness at all, it’s unneeded complexity.) Don’t put in the product and don’t bother telling anyone.

Rule 4: The newness you’re afraid of isn’t the newness you should be afraid of.

A good project plan starts with a good understanding of the newness. Then, the right project work is defined to make sure the newness gets the attention it deserves. The problem isn’t the newness you know, the problem is the unknown consequence of newness as it ripples through the commercialization engine. New product functionality gets engineering attention until it’s run to ground. But what if the newness ripples into new materials that can’t be made or new assembly methods that don’t exist? What if the new materials are banned substances? What if your multi-million dollar test stations don’t have the capability to accommodate the new functionality? What if the value proposition is new and your sales team doesn’t know how to sell it? What if the newness requires a new distribution channel you don’t have? What if your service organization doesn’t have the ability to diagnose a failure of the new newness?

Rule 5: The only way to develop the capability to handle newness is to pair a soon-to-be great project manager with an already great project manager.

It may sound like an inefficient way to solve the problem, but pairing the two project managers is a lot more efficient than letting a soon-to-be great project manager crash and burn. After an inexperienced project manager runs a project into the ground, what’s the first thing you do? You bring in a great project manager to get the project back on track and keep them in the saddle until the product launches. Why not assume the wheels will fall off unless you put a pro alongside the high potential talent?

Rule 6: When your best project managers tell you they need resources, give them what they ask for.

If you want to deliver new value to new customs there’s no better way than to develop good project managers. A good project manager instinctively knows the critical path; they know how the work is done; they know to unwind situations that needs to be unwound; they have the personal relationships to get things done when no one else can; because they are trusted, they can get people to bend (and sometimes break) the rules and feel good doing it; and they know what they need to successfully launch the product.

If you don’t know your critical path, you don’t know very much. And if your project managers don’t know the critical path, you should stop what you’re doing, pull hard on the emergency break with both hands and don’t release it until you know they know.

Image credit – Patrick Emerson

Battling the Dark Arts of Productivity and Accountability

How did you get to where you are? Was it a series of well-thought-out decisions or a million small, non-decisions that stacked up while you weren’t paying attention? Is this where you thought you’d end up? What do you think about where you are?

How did you get to where you are? Was it a series of well-thought-out decisions or a million small, non-decisions that stacked up while you weren’t paying attention? Is this where you thought you’d end up? What do you think about where you are?

It takes great discipline to make time to evaluate your life’s trajectory, and with today’s pace it’s almost impossible. Every day it’s a battle to do more than yesterday. Nothing is good enough unless it’s 10% better than last time, and once it’s better, it’s no longer good enough. Efficiency is worked until it reaches 100%, then it’s redefined to start the game again. No waste is too small to eliminate. In business there’s no counterbalance to the economists’ false promise of never-ending growth, unless you provide it for yourself.

If you make the time, it’s easy to plan your day and your week. But if you don’t make the time, it’s impossible. And it’s the same for the longer term – if you make the time to think about what you want to achieve, you have a better chance of achieving it – but it’s more difficult to make the time. Before you can make the time to step back and take look at the landscape, you’ve got to be aware that it’s important to do and you’re not doing it.

Providing yourself the necessary counterbalance is good for you and your family, and it’s even better for business. When you take a step back and slow your pace from sprint to marathon, you are happier and healthier and your work is better. When scout the horizon and realize you and your work are aligned, you feel better about the work and, therefore, you feel better about yourself. You’re a better person, partner and parent. And your work is better. When the work fits, everything is better.

Sometimes, people know their work doesn’t fit and purposefully don’t take a step back because it’s too scary to acknowledge there’s a problem. But burying your head doesn’t fix things. If you know you’re out of balance, the best thing to do is admit it and start a dialog with yourself and your boss. It won’t get better immediately, but you’ll feel better immediately. But most of the time, people don’t make time to take a step back because of the blistering pace of the work. There’s simply no time to think about the future. What’s missing is a weapon to battle the black arts of productivity and accountability.

The only thing powerful enough to counterbalance the forces of darkness is the very weapon we use to create the disease of hyper-productivity – the shared calendar (MS Calendar, Google Calendar). Open up the software, choose your day, choose your time and set up a one hour weekly meeting with yourself. Attendees: you. Agenda: take a couple deep breaths, relax and think. Change your settings so no one can see the meeting title and agenda and choose the color that makes people think the meeting is off-site. With your time blocked, you now have a reason to say no to other meetings. “Sorry, I can’t attend. I have a meeting.”

This simple mechanism is all you need.

No more excuses. Make the time for yourself. You’re worth it.

image credit :jovian (image modified)

Patents are supposed to improve profitability.

Everyone likes patents, but few use them as a business tool.

Everyone likes patents, but few use them as a business tool.

Patents define rights assigned by governments to inventors (really, the companies they work for) where the assignee has the right to exclude others from practicing the concepts described in the patent claims. And patent rights are limited to the countries that grant patents. If you want to get patent rights in a country, you submit your request (application) and run their gauntlet. Patents are a country-by-country business.

Patents are expensive. Small companies struggle to justify the expense of filing a single patent and big companies struggle to justify the expense of their portfolio. All companies want to reduce patent costs.

The patent process starts with invention. Someone must go to the lab and invent something. The invention is documented by the inventor (invention disclosure) and the invention is scored by a cross-functional team to decide if it’s worthy of filing. If deemed worthy, a clearance search is done to see if it’s different from all other patents, all products offered for sale, and all the other literature in the public domain (research papers, publications). Then, then the patent attorneys work their expensive magic to draft a patent application and file it with the government of choice. And when the rejection arrives, the attorneys do some research, address the examiner’s concerns and submit the paperwork.

Once granted, the fun begins. The company must keep watch on the marketplace to make sure no one sells products that use the patented technology. It’s a costly, never-ending battle. If infringement is suspected, the attorneys exchange documents in a cease-and-desist jousting match. If there’s no resolution, it’s time to go to court where prosecution work turns up the burn rate to eleven.

To reduce costs, companies try to reduce the price they pay to outside law firms that draft their patents. It’s a race to the bottom where no one wins. Outside firms get paid less money per patent and the client gets patents that aren’t as good as they could be. It’s a best practice, but it’s not best. Treating patent work as a cost center isn’t right. Patents are a business tool that help companies make money.

Companies are in business to make money and they do that by selling products for more than the cost to make them. They set clear business objectives for growth and define the market-customers to fuel that growth. And the growth is powered by the magic engine of innovation. Innovation creates products/services that are novel, useful and successful and patents protect them. That’s what patents do best and that’s how companies should use them.

If you don’t have a lot of time and you want to understand a patent, read the claims. If you have less time, read the independent claims. Chris Brown, Ph.D.

Patents are all about claims. The claims define how the invention is different (novel) from what’s tin the public domain (prior art). And since innovation starts with different, patents fit nicely within the innovation framework. Instead of trying to reduce patent costs, companies should focus on better claims, because better claims means better patents. Here are some thoughts on what makes for good claims.

Patent claims should capture the novelty of the invention, but sometimes the words are wrong and the claims don’t cover the invention. And when that happens, the patent issues but it does not protect the invention – all the downside with none of the upside. The best way to make sure the claims cover the invention is for the inventor to review the claims before the patent is filed. This makes for a nice closed-loop process.

When a novel technology has the potential to provide useful benefit to a customer, engineers turn those technologies into prototypes and test them in the lab. Since engineers are minimum energy creatures and make prototypes for only the technologies that matter, if the patent claims cover the prototype, those are good claims.

When the prototype is developed into a product that is sold in the market and the novel technology covered by the claims is what makes the product successful, those are good claims.

If you were to remove the patented technology from the product and your customer would notice it instantly and become incensed, those are the best claims.

Instead of reducing the cost of patents, create processes to make sure the right claims are created. Instead of cutting corners, embed your patent attorneys in the technology development process to file patents on the most important, most viable technology. Instead of handing off invention disclosures to an isolated patent team, get them involved in the corporate planning process so they understand the business objectives and operating plans. Get your patent attorneys out in the field and let them talk to customers. That way they’ll know how to spot customer value and write good claims around it.

Patents are an important business tool and should be used that way. Patents should help your company make money. But patents aren’t the right solution to all problems. Patent work can be slow, expensive and uncertain. A more powerful and more certain approach is a strong investment in understanding the market, ritualistic technology development, solid commercialization and a relentless pursuit of speed. And the icing on the top – a slathering of good patent claims to protect the most important bits.

Image credit – Matthais Weinberger

You probably don’t have an organizational capability gap.

The organizational capability of a company defines its ability to get things done. If you can’t pull it off, you have an organizational capability problem, or so the traditional thinking goes.

The organizational capability of a company defines its ability to get things done. If you can’t pull it off, you have an organizational capability problem, or so the traditional thinking goes.

If you don’t have enough people to do the work, and the work is not new, that’s not a capability gap, that’s an organizational capacity gap. Capacity gaps are filled in straightforward ways. 1.) You can hire more people like the ones who do the work today and train them with the people you already have. Or for machines – buy more of the old machines you know and love. 2.) Map the work processes and design out the waste. Find the piles of paper or long queues and the bottleneck will be right in front. Figure out how to get more work through bottleneck. Professional tip – ignore everything but the bottleneck because fixing a non-bottleneck will only make you tired and sweaty and won’t increase throughput. 3.) Move people and machines from the work to create a larger shortfall. If no one complains, it wasn’t a problem and don’t fix it. If the complaints skyrocket, use the noise to justify the first or second option. And don’t let your ego get in the way – bigger teams aren’t better, they’re just bigger.

If your company systematically piles too work on everyone’s plate, you don’t have an organizational capability problem, you have a leadership problem.

If you’re asked to put together a future state organization and define its new capabilities, you don’t have an organizational capability gap. A capability gap exists only when there’s a business objective that must be satisfied, and a paper exercise to create a future state organization is not a business objective. Before starting the work, ask for the company’s growth objectives and an explanation of the new work your team will have to do to achieve those objectives. And ask how much money has been budgeted (and approved) for the future state organization and when you can make the first hire. This will reduce the urgency of the exercise, and may stop it altogether. And everyone will know there’s no “organizational capability gap.”

If you’re asked to put together a project plan (with timeline and budget) to create a new technology and present the plan to the CEO next week, you have an organizational capability gap. If there’s a shortfall in the company’s growth numbers and the VP of business development calls you at home and tells you to put together a plan to create a new market in a new country and present it to her tomorrow, you have an organizational capability gap. If the VP of sales takes you to a fancy restaurant and asks you to make a napkin sketch of your plan to sell the new product through a new channel, you have an organizational capability gap.

Real organizational capability gaps are rare. Unless there’s a change, there can be no organizational capability gap. There can be no gap without a new business deliverable, new technology, new partnership, new product, new market, or new channel. And without a timeline and an approved budget, I don’t know what you have, but you don’t have organizational capability gap.

Image credit – Jehane

Strategic Planning is Dead.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

In the olden days (the early 2000s) the pace of change was slow enough that for most the next big thing was the same old thing, just twisted and massaged to look like the next big thing. But that’s not the case today. Today’s pace is exponential, and it’s time to behave that way. The next big thing has yet to be imagined, but with unimaginable computing power, smart phones, sensors on everything and a couple billion new innovators joining the web, it should be available on Alibaba and Amazon a week from next Thursday. And in three weeks, you’ll be able to buy a 3D printer for $199 and go into business making the next big thing out of your garage. Or, you can grasp tightly onto your success and ride it into the ground.

To move things forward, the first thing to do is to blow up the strategic planning process and sweep the pieces into the trash bin of a bygone era. And, the next thing to do is make sure the scythe of continuous improvement is busy cutting waste out of the manufacturing process so it cannot be misapplied to the process of re-imagining the strategic planning process. (Contrary to believe, fundamental problems of ineffectiveness cannot be solved with waste reduction.)

First, the process must be renamed. I’m not sure what to call it, but I am sure it should not have “planning” in the name – the rate of change is too steep for planning. “Strategic adapting” is a better name, but the actual behavior is more akin to probe, sense, respond. The logical question then – what to probe?

[First, for the risk minimization community, probing is not looking back at the problems of the past and mitigating risks that no longer apply.]

Probing is forward looking, and it’s most valuable to probe (purposefully investigate) fertile territory. And the most fertile ground is defined by your success. Here’s why. Though the future cannot be predicted, what can be predicted is your most profitable business will attract the most attention from the billion, or so, new innovators looking to disrupt things. They will probe your business model and take it apart piece-by-piece, so that’s exactly what you must do. You must probe-sense-respond until you obsolete your best work. If that’s uncomfortable, it should be. What should be more uncomfortable is the certainty that your cash cow will be dismantled. If someone will do it, it might as well be you that does it on your own terms.

Over the next year the most important work you can do is to create the new technology that will cause your most profitable business to collapse under its own weight. It doesn’t matter what you call it – strategic planning, strategic adapting, securing the future profitability of the company – what matters is you do it.

Today’s biggest risk is our blindness to the immense risk of keeping things as they are. Everything changes, everything’s impermanent – especially the things that create huge profits. Your most profitable businesses are magnates to the iron filings of disruption. And it’s best to behave that way.

Image credit – woodleywonderworks

Purposeful Violation of the Prime Directive

In Star Trek, the Prime Directive is the over-arching principle for The United Federation of Planets. The intent of the Prime Directive is to let a sentient species live in accordance with its normal cultural evolution. And the rules are pretty simple – do whatever you want as long as you don’t violate the Prime Directive. Even if Star Fleet personnel know the end is near for the sentient species, they can do nothing to save it from ruin.

In Star Trek, the Prime Directive is the over-arching principle for The United Federation of Planets. The intent of the Prime Directive is to let a sentient species live in accordance with its normal cultural evolution. And the rules are pretty simple – do whatever you want as long as you don’t violate the Prime Directive. Even if Star Fleet personnel know the end is near for the sentient species, they can do nothing to save it from ruin.

But what does it mean to “live in accordance with the normal cultural evolution?” To me it means “preserve the status quo.” In other words, the Prime Directive says – don’t do anything to challenge or change the status quo.

Though today’s business environment isn’t Star Trek and none of us work for Star Fleet, there is a Prime Directive of sorts. Today’s Prime Directive deals not with sentient species and their cultures but with companies and their business models, and its intent is to let a company live in accordance with the normal evolution of its business model. And the rules are pretty simple – do whatever you want as long as you don’t violate the Prime Directive. Even if company leaders know the end is near for the business model, they can do nothing to save it from ruin.

Business models, and their decrepit value propositions propping them up, don’t evolve. They stay just as they are. From inside the company the business model and value proposition are the very things that provide sustenance (profitability). They are known and they are safe – far safer than something new – and employees defend them as diligently as Captain Kirk defends his Prime Directive. With regard to business models, “to live in accordance with its natural evolution” is to preserve the status quo until it goes belly up. Today’s Prime Directive is the same as Star Trek’s – don’t do anything to challenge or change the status quo.

Innovation brings to life things that are novel, useful, and successful. And because novel is the same as different, innovation demands complete violation of today’s Prime Directive. For innovators to be successful, they must blow up the very things the company holds dear – the declining business model and its long-in-the-tooth value proposition.

The best way to help innovators do their work is to provide them phasers so they can shoot those in the way of progress, but even the most progressive HR departments don’t yet sanction phasers, even when set to “stun”. The next best way is to educate the company on why innovation is important. Company leaders must clearly articulate that business models have a finite life expectancy (measured in years, not decades) and that it’s the company’s obligation to disrupt and displace it.them.

The Prime Directive has a valuable place in business because it preserves what works, but it needs to be amended for innovation. And until an amendment is signed into law, company leaders must sanction purposeful violation of the Prime Directive and look the other way when they hear the shrill ring a phaser emanating from the labs.

Image credit – svenwerk

Tracking Toward The Future

It’s difficult to do something for the first time. Whether it’s a new approach, a new technology, or a new campaign, the mass of the past pulls our behavior back toward itself. And sadly, whether the past has been successful or not, its mass, and therefore it’s pull, are about the same. The past keeps us along the track of sameness.

It’s difficult to do something for the first time. Whether it’s a new approach, a new technology, or a new campaign, the mass of the past pulls our behavior back toward itself. And sadly, whether the past has been successful or not, its mass, and therefore it’s pull, are about the same. The past keeps us along the track of sameness.

Trains have tracks to enable them to move efficiently (cost per mile), and when you want to go where the train is heading, it’s all good. But when the tracks are going to the wrong destination, all that efficiency comes at the expense of effectiveness. Like we’re on rails, company history keeps us on track, even if it’s time for a new direction.

The best trains run on a ritualistic schedule. People queue up at same time every morning to meet their same predictable behemoth, and take comfort in slinking into their regular seats and turning off their brains. And this is the train’s trick. It uses its regularity to lull riders into a hazy state of non-thinking – get on, sit down, and I’ll get your there – to blind passengers from seeing its highly limited timetable and its extreme inflexibility. The train doesn’t want us to recognize that it’s not really about where the train wants to go.

Trains are powerful in their own right, but their real muscle comes from the immense sunk cost of their infrastructure. Previous generations invested billions in train stations, repair facilities, tight integration with bus lines, and the tracks, and it takes extreme strength of character to propose a new direction that doesn’t make use of the old, tired infrastructure that’s already paid for. Any new direction that requires a whole new infrastructure is a tough sell, and that’s why the best new directions transcend infrastructure altogether. But for those new directions that require new infrastructure, the only way to go is a modular approach that takes the right size bites.

Our worn tracks were laid in a bygone era, and the important destinations of yesteryear are no longer relevant. It’s no longer viable to go where the train wants; we must go where we want.

The Invisible Rut of Success

It’s easier to spot when it’s a rut of failure – product costs too high, product function is too low, and the feeding frenzy where your competitors eat your profits for lunch. Easy, yes, but still possible to miss, especially when everyone’s super busy cranking out heaps of the same old stuff in the same old way, and demonstrating massive amounts of activity without making any real progress. It’s like treading water – lots of activity to keep your head above water, but without the realization you’re just churning in the same place.

But far more difficult to see (and far more dangerous) is the invisible rut of success, where cranking out the same old stuff in the same old way is lauded. Simply put – there’s no visible reason to change. More strongly put, when locked in this invisible rut newness is shunned and newness makers are ostracized. In short, there’s a huge disincentive to change and immense pressure to deepen the rut.

To see the invisible run requires the help of an outsider, an experienced field guide who can interpret the telltale signs of the rut and help you see it for what it is. For engineering, the rut looks like cranking out derivative products that reuse the tired recipes from the previous generations; it looks like using the same old materials in the same old ways; like running the same old analyses with the same old tools; all-the-while with increasing sales and praise for improved engineering productivity.

And once your trusted engineering outsider helps you see your rut for what it is, it’s time to figure out how to pull your engineering wagon out of the deep rut of success. And with your new plan in hand, it’s finally time to point your engineering wagon in a new direction. The good news – you’re no longer in a rut and can choose a new course heading; the bad news – you’re no longer in a rut so you must choose one.

It’s difficult to see your current success as the limiting factor to your future success, and once recognized it’s difficult to pull yourself out of your rut and set a new direction. One bit of advice – get help from a trusted outsider. And who can you trust? You can trust someone who has already pulled themselves out of their invisible rut of success.

Wrestle Your Success To The Ground

Innovation, as a word, has become too big for its own good, and, as a word, is almost useless. Sure, it can be used to enable magical reinvention of business models and revolutionary products and technologies, but it can also be used to rationalize the rehash work we were going to do anyway. The words that send angry chills down the back of the would-be-innovative company – “We’re already doing it.”

Innovation, as a word, has become too big for its own good, and, as a word, is almost useless. Sure, it can be used to enable magical reinvention of business models and revolutionary products and technologies, but it can also be used to rationalize the rehash work we were going to do anyway. The words that send angry chills down the back of the would-be-innovative company – “We’re already doing it.”

When company leaders talk about doing more innovation, there’s a lot of pressure in the organization to point to innovative things already being done. The organization misinterprets the desire for more innovation as a negative commentary on their work. The mental dialog goes like this – We’re good at our work, we’re working as hard as we can, and we’re doing all we can to meet objectives – hey, look at this innovative stuff we’re doing. Clearly this isn’t what company leaders are looking for, but the word does have that influence.

What can feel better is to describe what is meant by innovation. Wherever we are, whatever successes we’ve had, we want to change our behaviors to create new, more profitable business models; create new products and technologies that obsolete our best, most profitable ones; and change our behaviors to create new, more profitable markets. The key is to acknowledge that our existing behaviors are the very thing that has created our success (and thank them for it), and to acknowledge the desire to build on our success by obsoleting it. When we ask for more innovation, we’re asking for new behaviors to dismantle our current day success behind us to create the next level of success.

There’s a tight link to innovation and failure – risk, learning, experimentation – but there’s a missing link with success. Acknowledgement of success helps the organization retain its self worth and helps them feel good about trying new stuff. However, even still, success is huge deterrent to innovation. Company success will retain the behaviors that created it, and more strongly, as new behaviors are injected, the antibodies of success will reject them. Our strength becomes our weakness.

Strong technologies become anchors to themselves; successful, stable, long-running markets hold tightly to resources that created them; and time-tested business models are above the law. New behaviors almost don’t stand a chance.

Fear of losing what we have is the number one innovation blocker. Where failure blocks innovation narrowly in the blast zone, success smears a thick layer of inaction across the organization. What’s most insidious, since we celebrate success, since we laud customer focus, since we track and reward efficiently doing what we’ve done, we systematically thicken and stiffen the layer that gums up innovation.

Instead of starting with a call-to-arms for innovation, it’s best to define company values, mission, and strategic objectives. Then, and only then, define innovation as the way to get there. First company objectives, then innovation as the path.

Innovation, as a word, isn’t important. What’s important are the new behaviors that will wrestle success to the ground, and pin it.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski