Posts Tagged ‘Problems’

Problems, Learning, Business Models, and People

If you know the right answer, you’re working on an old problem or you’re misapplying your experience.

If you know the right answer, you’re working on an old problem or you’re misapplying your experience.

If you are 100% sure how things will turn out, let someone else do it.

If there’s no uncertainty, there can be no learning.

If there’s no learning, your upstart competitors are gaining on you.

If you don’t know what to do, you’ve started the learning cycle.

If you add energy to your business model and it delivers less output, it’s time for a new business model.

If you wait until you’re sure you need a new business model, you waited too long.

Successful business models outlast their usefulness because they’ve been so profitable.

When there’s a project with a 95% chance to increase sales by 3%, there’s no place for a project with a 50% chance to increase sales by 100%.

When progress has slowed, maybe the informal networks have decided slower is faster.

If there’s something in the way, but you cannot figure out what it is, it might be you.

“A bouquet of wilting adapters” by rexhammock is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Is it time to break the logjam?

Clearing a logjam is not about increasing the force of the water. It’s about moving one log out of the way, watching what happens, and choosing the next log to move.

Crossing a raging river is not about pushing against the current. It’s about seeing what’s missing and using logs to build a raft.

Trekking across the tundra after crossing the raging river is not about holding onto the logs that helped you cross. It’s about seeing what’s not needed and leaving the raft by the river.

The trick is to know when to move the logs, when to use them to build a raft, and when to leave them behind.

Image credit: “Log Jam Mural _ Stillwater MN” by Kathleen Tyler Conklin is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Testing is an important part of designing.

When you design something, you create a solution to a collection of problems. But it goes far beyond creating the solution. You also must create objective evidence that demonstrates that the solution does, in fact, solve the problems. And the reason to generate this evidence is to help the organization believe that the solution solves the problem, which is an additional requirement that comes with designing something. Without this belief, the organization won’t go out to the customer base and convince them that the solution will solve their problems. If the sales team doesn’t believe, the customers won’t believe.

When you design something, you create a solution to a collection of problems. But it goes far beyond creating the solution. You also must create objective evidence that demonstrates that the solution does, in fact, solve the problems. And the reason to generate this evidence is to help the organization believe that the solution solves the problem, which is an additional requirement that comes with designing something. Without this belief, the organization won’t go out to the customer base and convince them that the solution will solve their problems. If the sales team doesn’t believe, the customers won’t believe.

In school, we are taught to create the solution, and that’s it. Here are the drawings, here are the materials to make it, here is the process documentation to build it, and my work here is done. But that’s not enough.

Before designing the solution, you’ve got to design the tests that create objective evidence that the solution actually works, that it provides the right goodness and it solves the right problems. This is an easy thing to say, but for a number of reasons, it’s difficult to do. To start, before you can design the right tests, you’ve got to decide on the right problems and the right goodness. And if there’s disagreement and the wrong tests are defined, the design community will work in the wrong areas to generate the wrong value. Yes, there will be objective evidence, and, yes, the evidence will create a belief within the organization that problems are solved and goodness is achieved. But when the sales team takes it to the customer, the value proposition won’t resonate and it won’t sell.

Some questions to ask about testing. When you create improvements to an existing product, what is the family of tests you use to characterize the incremental goodness? And a tougher question: When you develop a new offering that provides new lines of goodness and solves new problems, how do you define the right tests? And a tougher question: When there’s disagreement about which tests are the most important, how do you converge on the right tests?

Image credit — rjacklin1975

Problems, Solutions, and Complaints

If you see a problem, tell someone. But, also, tell them how you’d like to improve things.

If you see a problem, tell someone. But, also, tell them how you’d like to improve things.

Once you see a problem, you have an obligation to seek a solution.

Complaining is telling someone they have a problem but stopping short of offering solutions.

To stop someone from complaining, ask them how they might make the situation better.

Problems are good when people use them as a forcing function to create new offerings.

Problems are bad when people articulate them and then go home early.

Thing is, problems aren’t good or bad. It’s our response that determines their flavor.

If it’s your problem, it can never be our solution.

Sometimes the best solution to a problem is to solve a different one.

Problem-solving is 90% problem definition and 10% getting ready to define the problem.

When people don’t look critically at the situation, there are no problems. And that’s a big problem.

Big problems require big solutions. And that’s why it’s skillful to convert big ones into smaller ones.

Solving the right problem is much more important than solving the biggest problem.

If the team thinks it’s impossible to solve the problem, redefine the problem and solve that one.

You can relabel problems as “opportunities” as long as you remember they’re still problems

When it comes to problem-solving, there is no partial credit. A problem is either solved or it isn’t.

Stop reusing old ideas and start solving new problems.

Creating new ideas is easy. Sit down, quiet your mind, and create a list of five new ideas. There. You’ve done it. Five new ideas. It didn’t take you a long time to create them. But ideas are cheap.

Creating new ideas is easy. Sit down, quiet your mind, and create a list of five new ideas. There. You’ve done it. Five new ideas. It didn’t take you a long time to create them. But ideas are cheap.

Converting ideas into sellable products and selling them is difficult and expensive. A customer wants to buy the new product when the underlying idea that powers the new product solves an important problem for them. In that way, ideas whose solutions don’t solve important problems aren’t good ideas. And in order to convert a good idea into a winning product, dirt, rocks, and sticks (natural resources) must be converted into parts and those parts must be assembled into products. That is expensive and time-consuming and requires a factory, tools, and people that know how to make things. And then the people that know how to sell things must apply their trade. This, too, adds to the difficulty and expense of converting ideas into winning products.

The only thing more expensive than converting new ideas into winning products is reusing your tired, old ideas until your offerings run out of sizzle. While you extend and defend, your competitors convert new ideas into new value propositions that bring shame to your offering and your brand. (To be clear, most extend-and-defend programs are actually defend-and-defend programs.) And while you reuse/leverage your long-in-the-tooth ideas, start-ups create whole new technologies from scratch (new ideas on a grand scale) and pull the rug out from under you. The trouble is that the ultra-high cost of extend-and-defend is invisible in the short term. In fact, when coupled with reuse, it’s highly profitable in the moment. It takes years for the wheels to fall off the extend-and-defend bus, but make no mistake, the wheels fall off.

When you find the urge to create a laundry list of new ideas, don’t. Instead, solve new problems for your customers. And when you feel the immense pressure to extend and defend, don’t. Instead, solve new problems for your customers.

And when all that gets old, repeat as needed.

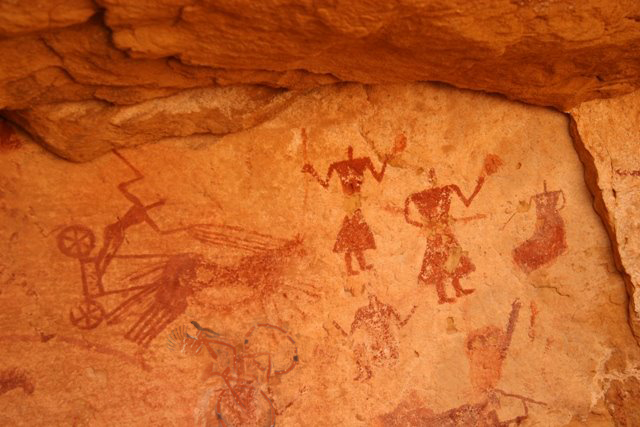

“Cave paintings” by allspice1 is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Do you have a problem?

If it’s your problem, fix it. If it’s not your problem, let someone else fix it.

If it’s your problem, fix it. If it’s not your problem, let someone else fix it.

If you fix someone else’s problem, you prevent the organization from fixing the root cause.

If you see a problem, say something.

If you see a problem, you have an obligation to do something, but not an obligation to fix it.

If someone tries to give you their stinky problem and you don’t accept it, it’s still theirs.

If you think the problem is a symptom of a bigger problem, fixing the small problem doesn’t fix anything.

If someone isn’t solving their problem, maybe they don’t know they have a problem.

If someone you care about has a problem, help them.

If someone you don’t care about has a problem, help them, too.

If you don’t have a problem, there can be no progress.

If you make progress, you likely solved a problem.

If you create the right problem the right way, you presuppose the right solution.

If you create the right problem in the right way, the right people will have to solve it.

If you want to create a compelling solution, shine a light on a compelling problem.

If there’s a big problem but no one wants to admit it, do the work that makes it look like the car crash it is.

If you shine a light on a big problem, the owner of the problem won’t like it.

If you shine a light on a big problem, make sure you’re in a position to help the problem owner.

If you’re not willing to contribute to solving the problem, you have no right to shine a light on it.

If you can’t solve the problem, it’s because you’ve defined it poorly.

Problem definition is problem-solving.

If you don’t have a problem, there’s no problem.

And if there’s no problem, there can be no solution. And that’s a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, how can you have a solution?

If you want to create the right problem, create one that tugs on the ego.

If you want to shine a light on an ego-threatening problem, make it as compelling as a car crash – skid marks and all.

If shining a light on a problem will make someone look bad, give them an opportunity to own it, and then turn on the lights.

If shining a light on a problem will make someone look bad, so be it.

If it’s not your problem, keep your hands in your pockets or it will become your problem.

But no one can give you their problem without your consent.

If you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t, the problem at hand isn’t your biggest problem.

If you see a problem but it’s not yours to fix, you’re not obliged to fix it, but you are obliged to shine a light on it.

When it comes to problems, when you see something, say something.

But, if shining a light on a big problem is a problem, well, you have a bigger problem.

“No Problem!” by Andy Morffew is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Without a problem there can be no progress.

Without a problem, there can be no progress.

And only after there’s too much no progress is a problem is created.

And once the problem is created, there can be progress.

When you know there’s a problem just over the horizon, you have a problem.

Your problem is that no one else sees the future problem, so they don’t have a problem.

And because they have no problem, there can be no progress.

Progress starts only after the calendar catches up to the problem.

When someone doesn’t think they have a problem, they have two problems.

Their first problem is the one they don’t see, and their second is that they don’t see it.

But before they can solve the first problem, they must solve the second.

And that’s usually a problem.

When someone hands you their problem, that’s a problem.

But if you don’t accept it, it’s still their problem.

And that’s a problem, for them.

When you try to solve every problem, that’s a problem.

Some problems aren’t worth solving.

And some don’t need to be solved yet.

And some solve themselves.

And some were never really problems at all.

When you don’t understand your problem, you have two problems.

Your first is the problem you have and your second is that you don’t know what your problem by name.

And you’ve got to solve the second before the first, which can be a problem.

With a big problem comes big attention. And that’s a problem.

With big attention comes a strong desire to demonstrate rapid progress. And that’s a problem.

And because progress comes slowly, fervent activity starts immediately. And that’s a problem.

And because there’s no time to waste, there’s no time to define the right problems to solve.

And there’s no bigger problem than solving the wrong problems.

When The Wheels Fall Off

When your most important product development project is a year behind schedule (and the schedule has been revved three times), who would you call to get the project back on track?

When your most important product development project is a year behind schedule (and the schedule has been revved three times), who would you call to get the project back on track?

When the project’s unrealistic cost constraints wall of the design space where the solution resides, who would you call to open up the higher-cost design space?

When the project team has tried and failed to figure out the root cause of the problem, who would you call to get to the bottom of it?

And when you bring in the regular experts and they, too, try and fail to fix the problem, who would you call to get to the bottom of getting to the bottom of it?

When marketing won’t relax the specification and engineering doesn’t know how to meet it, who would you call to end the sword fight?

When engineering requires geometry that can only be made by a process that manufacturing doesn’t like and neither side will give ground, who would you call to converge on a solution?

When all your best practices haven’t worked, who would you call to invent a novel practice to right the ship?

When the wheels fall off, you need to know who to call.

If you have someone to call, don’t wait until the wheels fall off to call them. And if you have no one to call, call me.

Image credit — Jason Lawrence

Now that you know your product is bad for the environment, what will you do?

If your products were bad for the environment, what would you do?

If your products were bad for the environment, what would you do?

If your best products were the worst for the environment, what would you do?

If you knew your products hurt the people that use them, what would you do?

If you knew your sales would be reduced if you told your customers that your products were bad for their health, what would you do?

If you knew a competitive technology was fundamentally less harmful to the environment, what would you do?

If you knew that competitive technology did not hurt the people that use it, what would you do?

If you knew that competitive technology was taking market share from you, what would you do?

If you knew that competitive technology was improving faster than yours, what would you do?

If you knew how to redesign your product to make it better for the environment, but that redesign would reduce the product’s performance in other areas, what would you do?

If that same redesign effort generated patented technology, what would you do?

So, what will you do?

Image credit — Shane Gorski

How To Know if You’re Moving in a New Direction

If you want to move in a new direction, you can call it disruption, innovation, or transformation. Or, if you need to rally around an initiative, call it Industrial Internet of Things or Digital Strategy. The naming can help the company rally around a new common goal, so take some time to argue about and get it right. But, settle on a name as quickly as you can so you can get down to business. Because the name isn’t the important part. What’s most important is that you have an objective measure that can help you see that you’ve stopped talking about changing course and started changing it.

If you want to move in a new direction, you can call it disruption, innovation, or transformation. Or, if you need to rally around an initiative, call it Industrial Internet of Things or Digital Strategy. The naming can help the company rally around a new common goal, so take some time to argue about and get it right. But, settle on a name as quickly as you can so you can get down to business. Because the name isn’t the important part. What’s most important is that you have an objective measure that can help you see that you’ve stopped talking about changing course and started changing it.

When it’s time to change course, I have found that companies error on the side of arguing what to call it and how to go about it. Sure, this comes at the expense of doing it, but that’s the point. At the surface, it seems like there’s a need for the focus groups and investigatory dialog because no one knows what to do. But it’s not that the company doesn’t know what it must do. It’s that no one is willing to make the difficult decision and own the consequences of making it.

Once the decision is made to change course and the new direction is properly named, the talk may have stopped but the new work hasn’t started. And this is when it’s time to create an objective measure to help the company discern between talking about the course change and actively changing the course.

Here it is in a nutshell. There can be no course change unless the projects change.

Here’s the failure mode to guard against. When the naming conventions in the operating plans reflect the new course heading but sitting under the flashy new moniker is the same set of tired, old projects. The job of the objective measure is to discern between the same old projects and new projects that are truly aligned with the new direction.

And here’s the other half of the nutshell. There can be no course change unless the projects solve different problems.

To discern if the company is working in a new direction, the objective measure is a one-page description of the new customer problem each project will solve. The one-page limit helps the team distill their work into a singular customer problem and brings clarity to all. And framing the problem in the customer’s context helps the team know the project will bring new value to the customer. Once the problem is distilled, everyone will know if the project will solve the same old problem or a new one that’s aligned with the company’s new course heading. This is especially helpful the company leaders who are on the hook to move the company in the new direction. And ask the team to name the customer. That way everyone will know if you are targeting the same old customer or new ones.

When you have a one-page description of the problem to be solved for each project in your portfolio, it will be clear if your company is working in a new direction. There’s simply no escape from this objective measure.

Of course, the next problem is to discern if the resources have actually moved off the old projects and are actively working on the new projects. Because if the resources don’t move to the new projects, you’re not solving new problems and you’re not moving in the new direction.

Image credit – Walt Stoneburner

Four Pillars of Innovation – People, Learning, Judgment and Trust

Innovation is a hot topic. Everyone wants to do it. And everyone wants a simple process that works step-wise – first this, then that, then success.

Innovation is a hot topic. Everyone wants to do it. And everyone wants a simple process that works step-wise – first this, then that, then success.

But Innovation isn’t like that. I think it’s more effective to think of innovation as a result. Innovation as something that emerges from a group of people who are trying to make a difference. In that way, Innovation is a people process. And like with all processes that depend on people, the Innovation process is fluid, dynamic, complex, and context-specific.

Innovation isn’t sequential, it’s not linear and cannot be scripted.. There is no best way to do it, no best tool, no best training, and no best outcome. There is no way to predict where the process will take you. The only predictable thing is you’re better off doing it than not.

The key to Innovation is good judgment. And the key to good judgment is bad judgment. You’ve got to get things wrong before you know how to get them right. In the end, innovation comes down to maximizing the learning rate. And the teams with the highest learning rates are the teams that try the most things and use good judgement to decide what to try.

I used to take offense to the idea that trying the most things is the most effective way. But now, I believe it is. That is not to say it’s best to try everything. It’s best to try the most things that are coherent with the situation as it is, the market conditions as they are, the competitive landscape as we know it, and the the facts as we know them.

And there are ways to try things that are more effective than others. Think small, focused experiments driven by a formal learning objective and supported by repeatable measurement systems and formalized decision criteria. The best teams define end implement the tightest, smallest experiment to learn what needs to be learned. With no excess resources and no wasted time, the team wins runs a tight experiment, measures the feedback, and takes immediate action based on the experimental results.

In short, the team that runs the most effective experiments learns the most, and the team that learns the most wins.

It all comes down to choosing what to learn. Or, another way to look at it is choosing the right problems to solve. If you solve new problems, you’ll learn new things. And if you have the sightedness to choose the right problems, you learn the right new things.

Sightedness is a difficult thing to define and a more difficult thing to hone and improve. If you were charged with creating a new business in a new commercial space and the survival of the company depended on the success of the project, who would you want to choose the things to try? That person has sightedness.

Innovation is about people, learning, judgement and trust.

And innovation is more about why than how and more about who than what.

Image credit – Martin Nikolaj Christensen

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski