Archive for the ‘Intellectual Intertia’ Category

What it Takes to Do New Work

What it takes to do new work.

Confidence to get it wrong and confidence to do it early and often.

Purposeful misuse of worst practices in a way that makes them the right practices.

Tolerance for not knowing what to do next and tolerance for those uncomfortable with that.

Certainty that they’ll ask for a hard completion date and certainty you won’t hit it.

Knowledge that the context is different and knowledge that everyone still wants to behave like it’s not.

Disdain for best practices.

Discomfort with success because it creates discomfort when it’s time for new work.

Certainty you’ll miss the mark and certainty you’ll laugh about it next week.

Trust in others’ bias to do what worked last time and trust that it’s a recipe for disaster.

Belief that successful business models have half-lives and belief that no one else does.

Trust that others will think nothing will come of the work and trust that they’re likely right.

Image credit — japanexpertna.se

The Five Hardships of Success

Everything has a half-life, but we don’t behave that way. Especially when it comes to success. The thinking goes – if it was successful last time, it will be successful next time. So, do it again. And again. It’s an efficient strategy – the heavy resources to bring it to life have already been spent. And it’s predictable – the same customers, the same value proposition, the same supply base, the same distribution channel, and the same technology. And it’s dangerous.

Everything has a half-life, but we don’t behave that way. Especially when it comes to success. The thinking goes – if it was successful last time, it will be successful next time. So, do it again. And again. It’s an efficient strategy – the heavy resources to bring it to life have already been spent. And it’s predictable – the same customers, the same value proposition, the same supply base, the same distribution channel, and the same technology. And it’s dangerous.

Success is successful right up until it isn’t. It will go away. But it will take time. A successful product line won’t fall off the face of the earth overnight. It will deliver profits year-over-year and your company will come to expect them. And your company will get hooked on the lifestyle enabled by those profits. And because of the addiction, when they start to drop off the company will do whatever it takes to convince itself all is well. No need to change. If anything, it’s time to double-down on the successful formula.

Here’s a rule: When your successful recipe no longer brings success, it’s not time to double-down.

Success’s decline will be slow, so you have time. But creating a new recipe takes a long time, so it’s time to declare that the decline has already started. And it’s time to learn how to start work on the new recipe.

Hardship 1 – Allocate resources differently. The whole company wants to spend resources on the same old recipes, even when told not to. It’s time to create a funding stream that’s independent of the normal yearly planning cycle. Simply put, the people at the top have to reallocate a part of the operating budget to projects that will create the next successful platform.

Hardship 2 – Work differently. The company is used to polishing the old products and they don’t know how to create new ones. You need to hire someone who can partner with outside companies (likely startups), build internal teams with a healthy disrespect for previous success, create mechanisms to support those teams and teach them how to work in domains of high uncertainty.

Hardship 3 – See value differently. How do you provide value today? How will you provide value when you can’t do it that way? What is your business model? Are you sure that’s your business model? Which elements of your business model are immature? Are you sure? What is the next logical evolution of how you go about your business? Hire someone to help you answer those questions and create projects to bring the solutions to life.

Hardship 4 – Measure differently. When there’s no customer, no technology and no product, there’s no revenue. You’ve got to learn how to measure the value of the work (and the progress) with something other than revenue. Good luck with that.

Hardship 5 – Compensate differently. People that create something from nothing want different compensation than people that do continuous improvement. And you want to move quickly, violate the status quo, push through constraints and create whole new markets. Figure out the compensation schemes that give them what they want and helps them deliver what you want.

This work is hard, but it’s not impossible. But your company doesn’t have all the pieces to make it happen. Don’t be afraid to look outside your company for help and partnership.

Image credit — Insider Monkey

The Difficulty of Commercializing New Concepts

If you have the data that says the market for the new concept is big enough, you waited too long.

If you have the data that says the market for the new concept is big enough, you waited too long.

If you require the data that verifies the market is big enough before pursuing new concepts, you’ll never pursue them.

If you’re afraid to trust the judgement of your best technologists, you’ll never build the traction needed to launch new concepts.

If you will sell the new concept to the same old customers, don’t bother. You already sold them all the important new concepts. The returns have already diminished.

If you must sell the new concept to new customers, it could create a whole new business for you.

If you ask your successful business units to create and commercialize new concepts, they’ll launch what they did last time and declare it a new concept.

If you leave it to your successful business units to decide if it’s right to commercialize a new concept created by someone else, they won’t.

If a new concept is so significant that it will dwarf the most successful business unit, the most successful business unit will scuttle it.

If the new concept is so significant it warrants a whole new business unit, you won’t make the investment because the sales of the yet-to-be-launched concept are yet to be realized.

If you can’t justify the investment to commercialize a new concept because there are no sales of the yet-to-be-launched concept, you don’t understand that sales come only after you launch. But, you’re not alone.

If a new concept makes perfect sense, you would have commercialized it years ago.

If the new concept isn’t ridiculed by the Status Quo, do something else.

If the new concept hasn’t failed three times, it’s not a worthwhile concept.

If you think the new concept will be used as you intend, think again.

If you’re sure a new concept will be a flop, you shouldn’t be. Same goes for the ones you’re sure will be successful.

If you’re afraid to trust your judgement, you aren’t the right person to commercialize new concepts.

And if you’re not willing to put your reputation on the line, let someone else commercialize the new concept.

Image credit – Melissa O’Donohue

Transcending a Culture of Continuous Improvement

We’ve been too successful with continuous improvement. Year-on-year, we’ve improved productivity and costs. We’ve improved on our existing products, making them slightly better and adding features.

Our recipe for success is the same as last year plus three percent. And because the customers liked the old one, they’ll like the new one just a bit more. And the sales can sell the new one because its sold the same way as the old one. And the people that buy the new one are the same people that bought the old one.

Continuous improvement is a tried-and-true approach that has generated the profits and made us successful. And everyone knows how to do it. Start with the old one and make it a little better. Do what you did last time (and what you did the time before). The trouble is that continuous improvement runs out of gas at some point. Each year it gets harder to squeeze out a little more and each year the return on investment diminishes. And at some point, the same old improvements don’t come. And if they do, customers don’t care because the product was already better than good enough.

But a bigger problem is that the company forgets to do innovative work. Though there’s recognition it’s time to do something different, the organization doesn’t have the muscles to pull it off. At every turn, the organization will revert to what it did last time.

It’s no small feat to inject new work into a company that has been successful with continuous improvement. A company gets hooked on the predictable results of continuous which grows into an unnatural aversion to all things different.

To start turning the innovation flywheel, many things must change. To start, a team is created and separated from the continuously improving core. Metrics are changed, leadership is changed and the projects are changed. In short, the people, processes, and tools must be built to deal with the inherent uncertainty that comes with new work.

Where continuous improvement is about the predictability of improving what is, innovation is about the uncertainty of creating what is yet to be. And the best way I know to battle uncertainty is to become a learning organization. And the best way to start that journey is to create formal learning objectives.

Define what you want to learn but make sure you’re not trying to learn the same old things. Learn how to create new value for customers; learn how to deliver that value to new customers; learn how to deliver that new value in new ways (new business models.)

If you’re learning the same old things in the same old way, you’re not doing innovation.

Purposeful Procrastination

There’s a useful trick when you want to do new work. It has some of the characteristics of procrastination, but it’s different. With procrastination, the problem solver waits to start the solving until it’s almost impossible to meet the deadline. The the solver uses the unreasonable deadline to create internal pressure so they can let go of all the traditional solving approaches. With no time for traditional approaches, the solver must let go of what worked and try a new approach.

There’s a useful trick when you want to do new work. It has some of the characteristics of procrastination, but it’s different. With procrastination, the problem solver waits to start the solving until it’s almost impossible to meet the deadline. The the solver uses the unreasonable deadline to create internal pressure so they can let go of all the traditional solving approaches. With no time for traditional approaches, the solver must let go of what worked and try a new approach.

The heart of the IBE is the Design Challenge, where a team with diverse perspective is brought together by a facilitator to solve a problem in five minutes. The unreasonable time constraint generates all the goodness that comes with procrastination, but, because it’s a problem solving exercise, there’s no drama. And like with procrastination, the teams deliver unimaginable results within an unrealistic time constraint.

What’s in the way?

If you want things to change, you have two options. You can incentivize change or you can move things out of the way that block change. The first way doesn’t work and the second one does. For more details, click this link at it will take you to a post that describes Danny Kahneman’s thoughts on the subject.

If you want things to change, you have two options. You can incentivize change or you can move things out of the way that block change. The first way doesn’t work and the second one does. For more details, click this link at it will take you to a post that describes Danny Kahneman’s thoughts on the subject.

And, also from Kahneman, to move things out of the way and unblock change, change the environment.

Change-blocker 1. Metrics. When you measure someone on efficiency, you get efficiency. And if people think a potential change could reduce efficiency, that change is blocked. And the same goes for all metrics associated with cost, quality and speed. When a change threatens the metric, the change will be blocked. To change the environment to eliminate the blocking, help people understand who the change will actually IMPROVE the metric. Do the analysis and educate those who would be negatively impacted if the change reduced the metric. Change their environment to one that believes the change will improve the metric.

Change-blocker 2. Incentives. When someone’s bonus could be negatively impacted by a potential change, that change will be blocked. Figure out whose incentive compensation are jeopardized by the potential change and help them understand how the potential change will actually increase their incentives. You may have to explain that their incentives will increase in the long term, but that’s an argument that holds water. Until they believe their incentives will not suffer, they’ll block the change.

Change-blocker 3. Fear. This is the big one – fear of negative consequences. Here’s a short list: fear of being judged, fear of being blamed, fear of losing status, fear of losing control, fear of losing a job, fear of losing a promotion, fear of looking stupid and fear of failing. One of the best ways to help people get over their fear is to run a small experiment that demonstrates that they have nothing to fear. Show them that the change will actually work. Show them how they’ll benefit.

Eliminating the things that block change is fundamentally different than pushing people in the direction of change. It’s different in effectiveness and approach. Start with the questions: “What’s in the way of change?” or “Who is in the way of change?” and then “Why are they in the way of change?” From there, you’ll have an idea what must be moved out of the way. And then ask: “How can their environment be changed so the change-blocker can be moved out of the way?”

What’s in the way of giving it a try?

Image credit B4bees

Business is about feelings and emotions.

If you use your sane-and-rational lenses and the situation doesn’t make sense, that’s because the situation is not governed by sanity and rationality. Yet, even though there’s a mismatch between the system’s behavior and sane-and-rational, we still try to understand the system through the cloudy lenses of sanity and rationality.

If you use your sane-and-rational lenses and the situation doesn’t make sense, that’s because the situation is not governed by sanity and rationality. Yet, even though there’s a mismatch between the system’s behavior and sane-and-rational, we still try to understand the system through the cloudy lenses of sanity and rationality.

Computer programs are sane and rational; Algorithms are sane and rational; Machines are sane and rational. Fixed inputs yield predicted outputs; If this, then that; Repeat the experiment and the results are repeated. In the cold domain of machines, computer programs and algorithms you may not like the output, but you’re not surprised by it.

But businesses are not run by computer programs, algorithms and machines. Businesses are run by people. And that’s why things aren’t always sane and rational in business.

Where computer programs blindly follow logic that’s coded into them, people follow their emotions. Where algorithms don’t decide what to do based on their emotional state, people do. And where machines aren’t afraid to try something new, people are.

When something doesn’t make sense to you, it’s because your assumptions about the underlying principles are wrong. If you see things that violate logic, it’s because logic isn’t the guiding principle. And if logic isn’t the guiding principle, the only other things that could be driving the irrationality are feelings and emotions. But if you think the solution is to make the irrational system behave rationally, be prepared to be perplexed and frustrated.

The underpinnings of management and leadership are thoughts, feelings and emotions. And, thoughts are governed by feelings and emotions. In that way, the currency of management and leadership is feelings and emotions.

If your first inclination is to figure out a situation using logic, don’t. Logic is for computers, and even that’s changing with deep learning. Business is about people. When in doubt, assess the feelings and emotions of the people involved. And once you understand their thoughts and feelings, you’ll know what to do.

Business isn’t about algorithms. Business is about people. And people respond based on their emotional state. If you want to be a good manager, focus on people’s feelings and emotions. And if you want to be a good leader, do the same.

Image credit: Guiseppe Milo

The only thing predictable about innovation is its unpredictability.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

You can’t do work in a new area and deliver predictable results on a predictable timetable. And if your boss asks you to do so, you’re working for the wrong person.

When it comes to innovation, “ecosystem,” as a word, is unskillful. It doesn’t bound or constrain, nor does it show the way. How about a map of the system as it is? How about defined boundaries? How about the system’s history? How about the interactions among the system elements? How about a fitness landscape and the system’s disposition? How about the system’s reason for being? The next evolution of the system is unpredictable, even if you call it an ecosystem.

If you can’t tolerate unpredictability, you can’t tolerate innovation.

Innovation isn’t about reducing risk. Innovation is about maximizing learning rate. And when all things go as predicted, the learning rate is zero. That’s right. Learning decreases when everything goes as planned. Are you sure you want predictable results?

Predictable growth in stock price can only come from smartly trying the right portfolio of unpredictable projects. That’s a wild notion.

Innovation runs on the thoughts, feelings, emotions and judgement of people and, therefore, cannot be predictable. And if you try to make it predictable, the best people, the people that know the drill, will leave.

The real question that connects innovation and predictability: How to set the causes and conditions for people to try things because the results are unpredictable?

With innovation, if you’re asking for predictability, you’re doing it wrong.

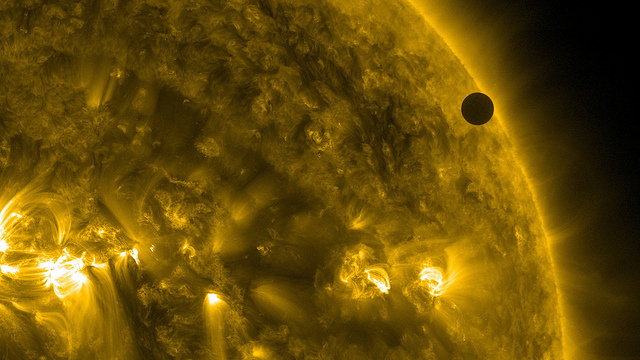

Image credit: NASA Goddard

You can’t innovate when…

Your company believes everything should always go as planned.

You still have to do your regular job.

The project’s completion date is disrespectful of the work content.

Your company doesn’t recognize the difference between complex and complicated.

The team is not given the tools, training, time and a teacher.

You’re asked to generate 500 ideas but you’re afraid no one will do anything with them.

You’re afraid to make a mistake.

You’re afraid you’ll be judged negatively.

You’re afraid to share unpleasant facts.

You’re afraid the status quo will be allowed to squash the new ideas, again.

You’re afraid the company’s proven recipe for success will stifle new thinking.

You’re afraid the project team will be staffed with a patchwork of part time resources.

You’re afraid you’ll have to compete for funding against the existing business units.

You’re afraid to build a functional prototype because the value proposition is poorly defined.

Project decisions are consensus-based.

Your company has been super profitable for a long time.

The project team does not believe in the project.

Image credit Vera & Gene-Christophe

For top line growth, think no-to-yes.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Where the factory creates bottom line growth, top line growth is generated in the market/customer domain. The best way I know to grow the top line is to broaden the applicability of your products and services. But, before you can broaden applicability, you’ve got to define applicability as it is. Define the limits of what your product can do – how much it can lift, how fast it can run a calculation and where it can be used. And for your service, define who can use it, where it can be used and what elements without customer involvement. And with the limits defined, you know where top line growth won’t come from.

Radical top line growth comes only when your products and services can be used in new applications. Sure, you can train your sales force to sell more of what you already have, but that runs out of gas soon enough. But, real top line growth comes when your services serve new customers in new ways. By definition, if you’re not trying to make your product work in new ways, you’re not going to achieve meaningful top line growth. And by definition, if you’re not creating new functionality for your services, you might as well be focusing on bottom line growth.

If your product couldn’t do it and now it can, you’re doing it right. If your service couldn’t be used by people that speak Chinese and now it can, you’re on your way. If your product couldn’t be used in applications without electricity and now it can, you’re on to something. If your service couldn’t run on a smartphone and now it can, well, you get the idea.

For the acid test, think no-to-yes.

If your product can’t work in application A, you can’t sell it to people who do that work. If your service can’t be used by visually impaired people, you’re not delivering value to them and they won’t buy it. Turning can’t into can is a big deal. But you’ve got to define can’t before you can turn it into can. If you want top line growth, take the time to define the limits of applicability.

No-to-yes is powerful because it creates clarity. It’s easy to know when a project will create no-to-yes functionality and when it won’t. And that makes it easy to stop projects that don’t deliver no-to-yes value and start projects that do.

No-to-yes is the key element of a compete-with-no-one approach to business.

image credit – liebeslakritze

How to Avoid a Cliff

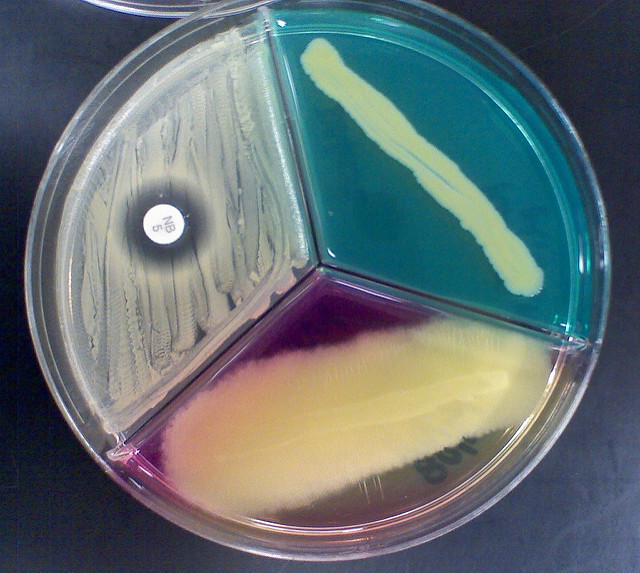

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

There are natural limits to evolutionary success in any single direction. When one trait is improved it pushes on the natural limits imposed by the environment. For example, a bacterium let loose in a friendly Petri dish will replicate until it eats all the food in the dish. Or, on a longer timescale, if the mass of a bird increases over generations when its food source is plentiful, the bird will get larger but will also get less agile. The predators who couldn’t catch the fast, little bird of old can easily catch and eat the sluggish heavyweight. In that way, there’s an edge condition created by the environmental Petri dishes and predators. And it’s the same with technological systems.

Companies and their technological systems evolve within their competitive environment by scanning the fitness landscape and deciding where to try to improve. The idea is to see preferential lines of improvement and create new technologies to take advantage of them. Like their smaller biological counterparts, companies are minimum energy creatures and want to maximize reward (profit) with minimum effort (expense) and will continue to leverage successful lines of evolution until it senses diminishing returns.

The diminishing returns are a warning sign that the company is approaching an edge condition (a Petri dish of a finite size). In landscape lingo, there’s a cliff on the horizon. In technology lingo, the rate of improvement of the technology is slowing. In either language, the edge is near and it’s time to evolve in a new direction because this current one is out of gas.

Like the bird whose mass increases over the generations when food is readily available, companies also get fat and slow when they successfully evolve in a single direction for too long. And like the bird, they get eaten by a more agile competitor/predator. And just as the replication rate of the bacterium accelerates as the food in the Petri dish approaches zero, a company that doesn’t react to a slowing rate of technological improvement is sure to outlive its business model.

Biology and technology are similar in that they try new things (create variants of themselves) in order to live another day. But there’s a big difference – where biology is blind (it doesn’t know what will work and what won’t), technology is sighted (people that create use their understanding to choose the variants they think will work best). And another difference is that biological evolution can build only on viable variants where technology can use mental models as scaffolds to skip non-viable embodiments to cross a chasm.

There’s no need to fall off the cliff. As a leading indicator, monitor the rate of improvement of your technology. If its rate of improvement is still accelerating, it’s time to develop the next line of evolution. If its rate is declining, you waited too long. It’s time to double down on two new lines of evolution because you’re behind the curve. And remember, like with the population of bacteria in the Petri dish, sales will keep growing right up until the business model runs out of food or a competitor eats you.

Image credit — Amanda

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski